1900 Amur anti-Chinese pogroms

This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in Chinese. (May 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

This article is missing information about specific background, aftermath and reviews. (May 2019) |

| 1900 Amur anti-Chinese Pogroms Gengzi Russian Disaster | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Russian invasion of Manchuria | |||||||||

In the Blagoveshchensk massacres, a Qing civilian was tied for execution. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 36,000 Russian soldiers and Cossacks | 22,000 civilians | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 198 officials died[1] | |||||||||

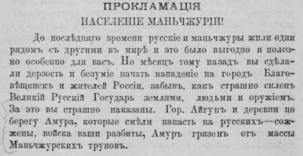

The 1900 Amur anti-Chinese Pogroms were a series of killings and reprisals of Qing subjects of various ethnicities including Manchus, Daur people, Han in Blagoveshchensk and in the Sixty-Four Villages East of the River in the Amur region during the same time as the spread of the Boxer Rebellion throughout China by Russian authorities, ultimately resulting in thousands of deaths, the loss of residency for Chinese living in the Sixty-Four Villages East of the River, and increased Russian control over the region. The Russian justification for the pogroms were attacks made on Russian infrastructure outside Blagoveshchensk by Chinese Boxers, which was then responded to by Russian force. The pogroms themselves occurred between 4–8 July (Old Style, O.S.; 17–21, New Style or N.S.), 1900.

Name[]

The name for the killings and reprisals that occurred in Amur is not standardized, and has been referred to by different names over time. The most common Chinese name for the pogroms is the Gengzi Russian Disaster (simplified Chinese: 庚子俄难; traditional Chinese: 庚子俄難; pinyin: Gēngzǐ é nán), but the two most major events in Blagoveshchensk and the Sixty-Four Villages East of the River are referred to as the Blagoveshchensk Massacre (simplified Chinese: 海兰泡惨案; traditional Chinese: 海蘭泡慘案; pinyin: Hǎilánpào cǎn'àn) and the Sixty-Four Villages East of the River Massacre (simplified Chinese: 江东六十四屯惨案; traditional Chinese: 江東六十四屯慘案; pinyin: Jiāngdōng liùshísì tún cǎn'àn) respectively.[2]

The Russian name of the pogroms in Blagoveshchensk is referred to as the Chinese Pogrom in Blagoveshchensk (Russian: Китайский погром в Благовещенске), while the killings and reprisals that took place in the Sixty-Four Villages East of the River are referred to as the Battle on the Amur (Russian: Бои на Амуре).[3]

Background[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (May 2019) |

Blagoveshchensk was founded on the territory ceded to Russia by Treaty of Aigun in 1858.

Process[]

Blagoveshchensk[]

This section is empty. You can help by . (May 2019) |

Sixty-Four Villages East of the River[]

Lieutenant-General Konstantin Nikolaevich Gribskiy ordered the expulsion of all Qing subjects who remained north of the river.[4] This included the residents of the villages, and Chinese traders and workers who lived in Blagoveshchensk proper, where they numbered anywhere between one-sixth and one-half of the local population of 30,000.[4][5] They were taken by the local police and driven into the river to be drowned. Those who could swim were shot by the Russian forces.[6] There were 1,266 households, including 900 Daurs and 4,500 Manchus in the area until the massacre.[7] Many Manchu villages were burned by Cossacks in the massacre according to Victor Zatsepine.[8]

Legacy[]

Andrew Higgins of The New York Times wrote that Chinese and Russian officials tended to not bring up the incidents during periods of good China-Russia relations or China-Soviet Union relations, while the incident was brought up after the Sino-Soviet split with people still alive who had been in the pogroms being interviewed by Chinese officials. Higgins stated that in 2020 Chinese and Russian officials purposefully avoided dealing with the incident.[9]

References[]

- ^ 孙蓉图; 徐希廉 (1974). 《瑷珲县志》 (in Chinese). Taipei: Cheng Wen Publishing Co., Ltd. pp. 209–210.

- ^ Gao, Yongsheng; Li, Lingbao (March 2004). ""庚子俄难"时限的再界定与思考" [Redefinition and Reflection on the Dates of the "Gengzi Russian Disaster"]. History of Heilongjiang (in Chinese). Xunke Country Local Records Office: 35–36 – via Ai Xueshu.

- ^ ""Боксерское" восстание в Китае в 1898 - 1901" ["Boxing" Uprising in China 1898-1901]. www.hrono.ru (in Russian). January 2000. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- ^ a b Paine, S.C.M. (1996). Imperial Rivals: China, Russia, and Their Disputed Frontier. Imperial Rivals: China, Russia, and Their Disputed Frontier. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-1-56324-724-8. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- ^ Yan, Jiaqi (February 2005). "中俄邊界問題的十個事實──回應俄羅斯駐中國大使館公使銜參贊岡察洛夫等人文章 (Ten facts about the Sino-Russian border problem: In reply to the essays of Russian Minister-Counselor to China Sergey Goncharov and other people)". Twenty-First Century. Chinese University of Hong Kong. 35. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- ^ Maxwell, Neville (June 2007). Iwashita, Akihiro (ed.). Eager Eyes Fixed on Eurasia (PDF). 21st Century COE Program Slavic Eurasian Studies. Sapporo: Slavic Research Center, Hokkaido University. pp. 47–72. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- ^ 俄罗斯帝国总参谋部. 《亚洲地理、地形和统计材料汇编》. 俄罗斯帝国: 圣彼得堡. 1886年: 第三十一卷·第185页 (俄语).

- ^ Higgins, Andrew (March 26, 2020). "On Russia-China Border, Selective Memory of Massacre Works for Both Sides". The New York Times.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew (2020-03-26). "On Russia-China Border, Selective Memory of Massacre Works for Both Sides". The New York Times. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

When China embraced the Soviet Union as a close ally [...] have muffled them further.

Further reading[]

- Yang, Chuang; Gao, Fei; Feng (September 2006), "海兰泡和江东六十四屯惨案 (The Tragic Case of Blagoveshchensk/Hailanpao and the Sixty-Four Villages East of the River)", 百年中俄关系 (A Century of China-Russia Relations), Beijing: World Affairs Press, ISBN 7501228760 (in Chinese)

- 1900 riots

- Mass murder in 1900

- July 1900 events

- Pogroms

- Boxer Rebellion

- War crimes in China

- 1900 in China

- 1900 in the Russian Empire

- War crimes in Russia

- China–Russia border

- China–Russian Empire relations