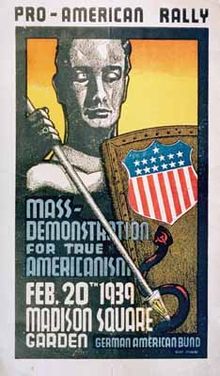

1939 Nazi rally at Madison Square Garden

Photograph from the event | |

| Date | February 20, 1939 |

|---|---|

| Venue | Madison Square Garden |

| Type | Nazi rally |

| Theme | American Nationalism Nazism White supremacy |

| Organised by | German American Bund |

| Participants | More than 20,000 |

| Arrests | 13 |

On February 20, 1939, a Nazi rally took place at Madison Square Garden, organized by the German American Bund. More than 20,000 people attended, and Fritz Julius Kuhn was a featured speaker. The Bund billed the event, which took place two days before George Washington's Birthday, as a pro-"Americanism" rally; the stage at the event featured a huge Washington portrait with swastikas on each side.[1]

Background[]

The German American Bund was a pro-Hitler organization in the United States before World War II. The group promoted Nazi propaganda in the United States, combining Nazi imagery with American patriotic imagery.[2]

The largely decentralized Bund was active in a number of regions, but attracted support only from a minority of German Americans.[2][3] The Bund was the most influential of a number of pro-Nazi German groups in the United States in the 1930s; others included the Teutonia Society and Friends of New Germany (also known as the Hitler Club). Alongside allied groups, such as the Christian Front, these organizations were virulently antisemitic.[3]

The pro-Nazi organizations in the U.S. were actively countered by anti-Nazi organizations led by American Jews, Americans, and others who opposed Hitlerism and supported a boycott of German goods. The Joint Boycott Committee held a rally at Madison Square Garden in 1937.[3]

Preparation for rally[]

Mayor LaGuardia realized the dangers posed by this rally and dispatched the highest number of police to a single event in the city's history.[4] 1,700 uniformed police officers patrolled outside the venue as well as 600 undercover detectives and non-uniformed officers scattered throughout the hall, and even 35 firefighters, armed with a heavy-duty fire hose in preparation of a riot. Bomb squads also combed the arena in response to a threat received a week earlier, boasting of a series of time activated devices to explode during the event.[5] New York was ready for the influx of Nazi rally attendees and was prepared to protect their guaranteed rights at all costs. Chief Inspector Louis F. Costuma illustrated this commitment to safety, telling the press, "We had enough police here to stop a revolution' in an interview in preparation for the rally."[6]

While Madison Square Garden had prepared itself for the German Bund, many around New York City considered the Nazi sect less welcome in their city. About 100,000 anti-Nazi protesters gathered around the arena in protest of the Bund, carrying signs stating "Smash Anti-Semitism" and "Drive the Nazis Out of New York."[7] A total of three attempts were made to break the arm-linking lines of police, the first of these, a group of World War One Veterans, wrapped in Stars and Stripes, were held off by police on mounted horseback, the next, a 'burly man carrying an American flag' and finally, a Trotskyist group known as the Socialist Workers Party, who like those before, had their efforts halted by police.[4] Chief Inspector Costuma's Police force acting security was exposed to an odd form of protest as well, characterized by the New York Times as:

"One of the most mystifying disturbances came from a blaring speaker set up in a second-floor room of a rooming house at the southern corner of Forty-ninth Street and Eight Avenue. Shortly before 8 o'clock it began blaring out a denunciation of Nazis and urging "Be American, Stay at Home." Upon investigation, the room was found untenanted: the voice of these 'denunciations' came from a record, timed to go off at 7:55 pm.[4]

Full of dramatics, the night's main act saw Joseph Goldstien, a former New York magistrate, exit a taxi cab in front of the rally holding a summons for the arrest of Fritz Julius Kuhn in relation to a criminal libel suit filed earlier. Goldstien, like all other opposing efforts to gain admittance to the Garden, was stopped by police, this time by Inspector Costuma himself, denying the former magistrate entry based on the failure to present a ticket. As the night went on, outside Madison Square Garden, a total of 13 people were arrested in protest of the rally. Their names, ages, charges and sentences (if available) are included below:[8]

- Isadore Greenbaum (26) - disorderly conduct (rushing the stage) - $25 fine

- John Doe (Fred Ryde) - disorderly conduct - $2 fine

- Lawerence Paladri - disorderly conduct - $2 fine

- Peter Saunders (34) - disorderly conduct and cruelty to animals (lunged on a mounted officer)

- George Mason (19) - alleged to "have seized a policeman," ran into and smashed glass at a restaurant - $10 fine

- Stephen Carmalt (20) - disorderly conduct - suspended sentence

- Robert Lee (39) - disorderly conduct - $10 fine

- J Walter Flynn (32) - $10 fine

- Michael Naradich (26) - disorderly conduct

- Peter Shopes (22) - disorderly conduct

- Lionel Sheppard (26) - disorderly conduct

- Abe Dollinger (27) - disorderly conduct

- Enfrim Lidew (50) - disorderly conduct

Rally[]

The rally took place at a time when the German American Bund's membership was dropping; Kuhn hoped that a provocative high-profile event would reverse the group's declining fortunes.[2] The pro-Nazi Bund was unpopular in New York City, and some called for the event to be banned. Mayor Fiorello La Guardia allowed the event to go forward, correctly predicting that the Bund's highly publicized spectacle would further discredit them in the public eye.[2]

The event was highly choreographed in the fascist style, with uniformed Bund members carrying American and Nazi flags, the display of the Nazi salute, and the playing of martial music and German folk songs.[2]

The rally began at 8 pm[2] with a rendition of "The Star-Spangled Banner", sung by Margarete Rittershaush. Next, James Wheeler-Hill, national secretary of the Bund, opened the night with the statement that "if George Washington were alive today, he would be friends with Adolf Hitler."[9] Calling upon his fellow Americans, Wheller-Hill challenged Bund members to restore America to the 'True Americans' while condemning President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Secretary of the Interior, Harold L. Ickes for attacking Nazi officials. Midwestern Gau leader, George Froboese was next to speak, pushing themes of 'Jewish world domination' blaming the 'oriental cunning of the Jew Karl Marx-Mordecais for the class warfare felt across the country.'[10] West Coast leader, Hermann Schwinn chose to denounce the Jewish control of Hollywood and news industries, following a common theme of the night with a fantastically anti-semitic run-on sentence, "Everything inimical to those Nations which have freed themselves of alien domination is 'News' to be played up and twisted to fan the flames of hate in the hearts of Americans, whereas the Menace of Anti-National, Gold-Hating Jewish-Bolshevism, is deliberately minimized"[11]

Last to speak, the Bundersfuhrer himself, Fritz Kuhn continued to push the anti-Semitic theme, going as far as to refer to President Roosevelt as 'Rosenfield' and the man to which he promised to make no anti-Semitic remarks, Fiorello "Jew Lumpen" LaGuardia himself.[12] All came to an immediate halt as in the middle of Kuhn's final speech, a man dressed in blue broke through the lines of OD men and ran onto the stage and charged at the speaker. Quickly swarmed by the Ordnungsdienst, he was subdued in an effective routine of punches and stomps exemplifying an 'uncanny replication of Nazi thuggery' [as] a pack of uniformed men blaste[ed] away with fists and boots on a lone Jewish victim."[13] Later identified as 26-year-old plumbing assistant Isadore Greenbaum, the lone victim was pulled away by a team of police, saving the young man from serious injury. Attempting to control the riled-up crowd, Kuhn delivered his rousing finish, advocating for an America ruled by White Gentiles, free from a Jewish Hollywood and news. "The Bund is open to you, provided you are sincere, of good character, of White Gentile Stock, and an American Citizen imbued with patriotic zeal. Therefore: Join!" As Kuhn exited the stage, 20 thousand Bund members chanted "Free America! Free America! Free America!" in the biggest Nazi rally in United States history.

At 11:15, members of the Bund buttoned up their overcoats, conveniently hiding their uniforms, and were escorted through police lines along Fifty-Second amid the crowds of protesters waiting outside. Ralliers were greeted with a roar of catcalls, jeers, and even a few punches, but by midnight, all was quiet, or as quiet as it could be in downtown New York.[4]

Isadore Greenbaum never intended to run onto the stage. A former deck engineer and chief petty officer, Greenbaum snuck into the rally, but his anger quickly took hold of him as he listened to Kuhn speak. Speaking years later in 1989, Greenbaum characterized his actions as "I went down to the Garden without any intention of interrupting, but being that they talked so much against my religion and there was so much persecution I lost my head and I felt it was my duty to talk".[14] When asked about the cause of his actions, Greenbaum quickly rebutted with "Gee, what would you have done if you were in my place listening to that s.o.b. hollering against the government and publicly kissing [Adolf] Hitler's behind - while thousands cheered? Well, I did it."[15] For his actions in disturbing the biggest Nazi rally in the United States, Greenbaum was sentenced to 10 days in jail, but instead paid a $25 fine.[16]

Aftermath[]

Shortly after the rally, the Bund rapidly declined. Two months after the rally, the film Confessions of a Nazi Spy was released by Warner Brothers, ridiculing the Nazis and their American sympathizers. The Bund also came under investigation. After its financial records were seized in a raid on the group's Yorkville, Manhattan headquarters, authorities discovered that $14,000 (about $250,000 in 2018 dollars) raised by the Bund in the rally was unaccounted for, having been spent by Kuhn on his mistress and various personal expenses. Kuhn was convicted of embezzlement in December 1939 and sent to Sing Sing prison.[2] Kuhn's successor as Bund leader was Gerhard Wilhelm Kunze, a spy for German military intelligence who fled the United States in November 1941. The final Bund national leader was George Froboese, who was in charge of the organization when Germany declared war on the United States. Froboese committed suicide in 1942, after receiving a federal grand jury subpoena.[2]

In popular culture[]

The rally was featured in Frank Capra's wartime documentary series Why We Fight.[17]

Actual footage of the rally was incorporated into a fictional newsreel created for the 2004 Star Trek: Enterprise episode "Storm Front," illustrating an alternate history in which the Nazis invaded and occupied the United States with the help of aliens from the future.[18]

The short 2017 documentary film A Night at the Garden is about the rally.[19]

See also[]

Further reading[]

- Diamond, Sander, The Nazi Movement in the United States 1924-1941, (London: Cornell University Press, 1974)

- Bell Lelland, "The Failure of Nazism in America: The German American Bund, 1936-1941, Political Science Quarterly, Vol. 85, [4] (December 1970)

- Bernstien, Arnie, Swastika Nation, Fritz Kuhn and the Rise and Fall of the German-American Bund, (New York City: St. Martin's Press, 2013)

- Bump Philip, "When Nazis rallied in Manhattan, one Working-Class Jewish Man From Brooklyn Took Them on" The Washington Post, February 20, 2019

- Hart Bradley W, Hitler's American Friends; the Third Reich's Supporters in the United States, (New York: St. Martin's Press, 2018

References[]

- ^ Bort, Ryan (February 19, 2019). "When Nazis Took Over Madison Square Garden". Rolling Stone.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bradley W. Hart, Hitler's American Friends: The Third Reich's Supporters in the United States (St. Martin's/Dunne, 2018).

- ^ a b c Eli Lederhendler, American Jewry: A New History (Cambridge University Press, 2017), p. 230.

- ^ a b c d "22,000 Nazis Hold Rally in Garden; Police Check Foes; Scenes as German-American Bund Held Its 'Washington Birthday' Rally Last Night". The New York Times. February 21, 1939. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ "Bund Rally Bomb Rumor Fails to Worry Mayor," New York Times, February 21, 1939.

- ^ Bernstien, Arnie, Swastika Nation, Fritz Kuhn and the Rise and Fall of the German-American Bund, (New York City: St. Martin's Press, 2013)

- ^ Bernstien, Arnie, Swastika Nation, Fritz Kuhn and the Rise and Fall of the German-American Bund, (New York City: St. Martin's Press, 2013)

- ^ "TimesMachine: Tuesday February 21, 1939 - NYTimes.com". timesmachine.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- ^ "Free America!" The German American Bund at Madison Square Garden, February 20, 1939. Speeches by J. Wheeler-Hill, Rudolf Marman, George Froboese, Hermann Schwinn, G. William Kunze, and the Bund Fuehrer: Fritz Kuhn

- ^ "Free America!" The German American Bund at Madison Square Garden, February 20, 1939. Speeches by J. Wheeler-Hill, Rudolf Marman, George Froboese, Hermann Schwinn, G. William Kunze, and the Bund Fuehrer: Fritz Kuhn

- ^ "Free America!" The German American Bund at Madison Square Garden, February 20, 1939. Speeches by J. Wheeler-Hill, Rudolf Marman, George Froboese, Hermann Schwinn, G. William Kunze, and the Bund Fuehrer: Fritz Kuhn

- ^ "Free America!" The German American Bund at Madison Square Garden, February 20, 1939. Speeches by J. Wheeler-Hill, Rudolf Marman, George Froboese, Hermann Schwinn, G. William Kunze, and the Bund Fuehrer: Fritz Kuhn

- ^ Maloney Russel, "Heil Washington!" The New Yorker, April 4, 1939

- ^ Bump Philip, "When Nazis rallied in Manhattan, one Working-Class Jewish Man From Brooklyn Took Them on" The Washington Post, February 20, 2019.

- ^ Bump Philip, "When Nazis rallied in Manhattan, one Working-Class Jewish Man From Brooklyn Took Them on" The Washington Post, February 20, 2019.

- ^ Bump Philip, "When Nazis rallied in Manhattan, one Working-Class Jewish Man From Brooklyn Took Them on" The Washington Post, February 20, 2019.

- ^ Gunter, Matthew C. (2011-12-01). The Capra Touch: A Study of the Director's Hollywood Classics and War Documentaries, 1934-1945. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-8828-5.

- ^ "Star Trek: Enterprise – Storm Front, Part II (Review)". the m0vie blog. 2016-05-05. Retrieved 2019-03-31.

- ^ Buder, Emily (October 10, 2017). "Footage of German American Bund Nazi Rally in Madison Square Garden in 1939". The Atlantic.

- 1939 in New York City

- 20th century in Manhattan

- February 1939 events

- Antisemitic attacks and incidents in the United States

- Events in New York City

- German American Bund

- Madison Square Garden

- Nazi propaganda