1977 Dutch train hijacking

| 1977 Dutch train hostage crisis | |

|---|---|

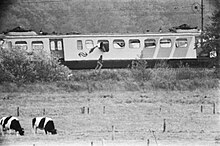

Hijacker running past the hijacked train with a South-Moluccan flag | |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 53°7′N 6°36′E / 53.117°N 6.600°ECoordinates: 53°7′N 6°36′E / 53.117°N 6.600°E |

| Date | 23 May – 11 June 1977 |

| Target | Train |

Attack type | Hostage-taking |

| Weapons | Guns / Handguns |

| Deaths | 8 (including 6 perpetrators) |

| Injured | 6 |

| Perpetrators | Moluccan youth (9 perpetrators) |

| Motive | A free South Moluccan Republic (Republik Maluku Selatan) |

On 23 May 1977, a train was hijacked near the village of Glimmen, Groningen, Netherlands. Nine armed Moluccans pulled the emergency brake around 09:00 and took about 50 people hostage. The hijacking lasted for 20 days and ended with a raid by the Dutch anti-terrorist special forces, during which two hostages and six hijackers were killed.

At the same time, four other South-Moluccans took hostages at an elementary school in Bovensmilde, around 20 km (12 mi) away.

This was the second train hijacking in the Netherlands and, like the train hijacking in 1975 in Wijster, was perpetrated by Moluccans.

Background[]

After fighting for the Dutch in the Dutch East Indies, the South Moluccans were forcibly exiled to the Netherlands, with the Dutch government promising that they would eventually get their own independent state, Republic of South Maluku. After about 25 years of living in temporary camps, often in poor conditions, the South Moluccans felt that the Dutch government had failed to fulfil its promise. It was then that some members of the South Moluccans' younger generation started a series of radical action to bring attention to their cause.

See Republik Maluku Selatan for more information about the RMS case.

Developments[]

At the same time four other South-Moluccans started taking hostages at a primary school in the village of Bovensmilde; they took 105 children and five teachers hostage. With these combined actions the hijackers wanted to force the (recently resigned) Dutch government to keep their promises about their RMS, break diplomatic ties with the Indonesian government and release 21 Moluccan prisoners involved in the hostage actions in 1975. An ultimatum was set for 25 May at 14:00 with the hijackers threatening to blow up the train and the school. The hostages were forced to help blinding all the windows so for a long period nobody knew about what happened inside the train; it was only near the end of the hostage taking that electronic eavesdropping devices were installed by marines. About 2000 marines and soldiers were stationed both at the train and the school.

For the date of 25 May, the elections for the Dutch parliament were planned. The leaders of the different parties agreed to cancel their election campaigns but the elections itself would take place on the planned date.

After the ultimatum expired, the hijackers announced new demands; They wanted an airplane from the airport of Schiphol and to fly out with the 21 to be freed prisoners, the five teachers, and all hijackers. By means of electronic eavesdropping, minister of Justice Van Agt (under resignation) knew that the hostages were not in danger, so the government let this second ultimatum pass as well.

- 09:00 23 May: Start of the hijack

- 24.May: The national broadcaster NOS reads the letter with the demands

- 25 May: Elections for national parliament, ultimatum expires without anything happening

- 26 May: A handcuffed hostage is taken outside the train and then taken aboard again

- 28 May: Hostages clean up the train, 60 activists offer themselves as alternative hostages

- 29 May: Negotiations about releasing a pregnant woman are cut off

- 30 May: Second week of crisis

- 31 May: For the first time the hijackers ask for a negotiator

- 1 June: The hijackers ask for an ambulance but later retract the request

- 4 June: Two negotiators talk for hours with the hijackers

- 5 June: Two pregnant women, including (later mayor of Utrecht), are allowed to leave the train

- 8 June: An ill passenger is released

- 9 June: Two negotiators talk again to the hijackers for hours

- 05:00 June 11: In the morning the crisis is ended after 482 hours

Negotiators[]

J.A. Manusama, then president of the RMS, and Rev. Metiarij acted as negotiators during the crisis.

Because of some disease in the school (probably caused by the food distributed in the school), the hijackers decided to release the children, but keep the teachers. According to medical doctor Frans Tutuhatunewa (later successor as RMS president), there was no health issue with the hostages in the train. Nevertheless, the health conditions of these hostages were used as an argument for the later attack on the train.

The attack[]

On 11 June 1977 at 05:00, almost three weeks after the start of the hijacking, six F-104 jet fighters of the Royal Netherlands Air Force overflew the train at low altitude, with the purpose of disorienting the hijackers and also make the hostages duck down to the floor of the train where they would be relatively safe. One of the pilots was Dick Berlijn, who later became Chief of the Netherlands Defence Staff.

Then marines of the special anti-terrorist unit Bijzondere Bijstands Eenheid (BBE) started shooting at the train; an estimated 15,000 bullets were shot at the train. The marines aimed at the first class and in-between compartments with the doors because they knew these were the areas where the hijackers were hiding. One of the hostages killed was in such a compartment because she had been allowed there by the hijackers. Six hijackers were killed.

Aftermath[]

Three hijackers survived and were later convicted to sentences from six to nine years.

In 2007 there was a memorial service for the killed hijackers;[1] Two of the hijackers, motivated by a conversion to Christianity, had a meeting with former victims in 2007.[2]

According to official sources, six of the hijackers were killed by the crossfire of bullets shot at the train. However many Moluccans believe that they were killed deliberately. On 1 June 2013 it was reported that an investigation by journalist Jan Beckers and one of the former hijackers, Junus Ririmasse, had concluded that three and possibly four of the hijackers were still alive when the train was stormed and executed by marines.[3] In November 2014, it was revealed that Dries van Agt, Justice Minister at the time, allegedly ordered that none of the hijackers were to leave the train alive.[4] An in-depth investigation, of which the results were published in November 2014, concluded however that no execution has taken place, but there were unarmed hijackers killed by marines.[5][6] In 2018, a Dutch court ruled that the Dutch government did not have to pay compensation to relatives of two of the hijackers killed by marines. The ruling was upheld on appeal on 1 June 2021.[7]

In popular culture[]

In 2009, , a Dutch- and Ambonese Malay-languages television film was made about this hostage crisis, directed by Hanro Smitsman.

See also[]

- 1975 Indonesian consulate hostage crisis

- 1978 Dutch province hall hostage crisis

- Attempt at kidnapping Juliana of the Netherlands

- List of hostage crises

- Terrorism in the European Union

References[]

- ^ (in Dutch) Article in NRC newspaper Archived 2007-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ (in Dutch) Description of TV-program of the EO(public evangelical broadcaster)[permanent dead link]

- ^ "'Treinkapers De Punt geliquideerd'" (in Dutch). Dagblad van het Noorden. 1 June 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-09-19. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

- ^ "Train hijackers ordered executed by Justice minister". NL Times. 16 October 2014.

- ^ "Unarmed hijackers killed in train hijacking". NL Times. 20 November 2014.

- ^ "Reconstruction video of the events during the marine attack on the train on the website of the Ministry of Defense". Archived from the original on 2014-12-13. Retrieved 2014-12-07.

- ^ "Dutch state does not have to pay damages for shooting Moluccan train hostage takers". Dutch News. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

External links[]

![]() Media related to Dutch train hostage crisis 1977 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dutch train hostage crisis 1977 at Wikimedia Commons

- Article from 1977 in Time magazine

- Article in BBC "on this day"

- (in Dutch) Dutch Polygoon newsreel images from 1977

- (in Dutch) Dutch Polygoon newsreel images of the military action from 1977

- (in Dutch) Images from the armoured car unit involved in the action

- (in Dutch) Images in the Dutch National Archive

- South Moluccan Suicide Commando in MIPT Terrorism Knowledge Base

- 1977 crimes in the Netherlands

- History of Drenthe

- Hostage taking in the Netherlands

- Moluccan Dutch

- Terrorist incidents in Europe in 1977

- Terrorist incidents on railway systems in Europe

- Hijacking

- Tynaarlo

- Terrorist incidents in the Netherlands in the 1970s

- 1970s murders in the Netherlands

- 1977 murders in Europe