3D bioprinting

Three dimensional (3D) bioprinting is the utilization of 3D printing–like techniques to combine cells, growth factors, and/or biomaterials to fabricate biomedical parts, often with the aim of imitating natural tissue characteristics. Generally, 3D bioprinting can utilize a layer-by-layer method to deposit materials known as bioinks to create tissue-like structures that are later used in various medical and tissue engineering fields.[1] 3D bioprinting covers a broad range of bioprinting techniques and biomaterials.

Currently, bioprinting can be used to print tissues and organs to help research drugs and pills.[2] However, innovations span from bioprinting of extracellular matrix to mixing cells with hydrogels deposited layer by layer to produce the desired tissue.[3] In addition, 3D bioprinting has begun to incorporate the printing of scaffolds. These scaffolds can be used to regenerate joints and ligaments.[4]

Process[]

3D bioprinting generally follows three steps, pre-bioprinting, bioprinting, and post-bioprinting.[5][6]

Pre-bioprinting[]

Pre-bioprinting is the process of creating a model that the printer will later create and choosing the materials that will be used. One of the first steps is to obtain a biopsy of the organ. Common technologies used for bioprinting are computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). To print with a layer-by-layer approach, tomographic reconstruction is done on the images. The now-2D images are then sent to the printer to be made. Once the image is created, certain cells are isolated and multiplied.[5] These cells are then mixed with a special liquefied material that provides oxygen and other nutrients to keep them alive. In some processes, the cells are encapsulated in cellular spheroids 500μm in diameter. This aggregation of cells does not require a scaffold, and are required for placing in the tubular-like tissue fusion for processes such as extrusion.[7]: 165

Bioprinting[]

In the second step, the liquid mixture of cells, matrix, and nutrients known as bioinks are placed in a printer cartridge and deposited using the patients' medical scans.[8] When a bioprinted pre-tissue is transferred to an incubator, this cell-based pre-tissue matures into a tissue.

3D bioprinting for fabricating biological constructs typically involves dispensing cells onto a biocompatible scaffold using a successive layer-by-layer approach to generate tissue-like three-dimensional structures.[9] Artificial organs such as livers and kidneys made by 3D bioprinting have been shown to lack crucial elements that affect the body such as working blood vessels, tubules for collecting urine, and the growth of billions of cells required for these organs. Without these components the body has no way to get the essential nutrients and oxygen deep within their interiors.[9] Given that every tissue in the body is naturally composed of different cell types, many technologies for printing these cells vary in their ability to ensure stability and viability of the cells during the manufacturing process. Some of the methods that are used for 3D bioprinting of cells are photolithography, magnetic 3D bioprinting, stereolithography, and direct cell extrusion.[7]: 196

Post-bioprinting[]

The post-bioprinting process is necessary to create a stable structure from the biological material. If this process is not well-maintained, the mechanical integrity and function of the 3D printed object is at risk.[5] To maintain the object, both mechanical and chemical stimulations are needed. These stimulations send signals to the cells to control the remodeling and growth of tissues. In addition, in recent development, bioreactor technologies[10] have allowed the rapid maturation of tissues, vascularization of tissues and the ability to survive transplants.[6]

Bioreactors work in either providing convective nutrient transport, creating microgravity environments, changing the pressure causing solution to flow through the cells, or add compression for dynamic or static loading. Each type of bioreactor is ideal for different types of tissue, for example compression bioreactors are ideal for cartilage tissue.[7]: 198

Bioprinting approach[]

Researchers in the field have developed approaches to produce living organs that are constructed with the appropriate biological and mechanical properties. 3D bioprinting is based on three main approaches: Biomimicry, autonomous self-assembly and mini-tissue building blocks.[11]

Biomimicry[]

The first approach of bioprinting is called biomimicry. The main goal of this approach is to create fabricated structures that are identical to the natural structure that are found in the tissues and organs in the human body. Biomimicry requires duplication of the shape, framework, and the microenvironment of the organs and tissues.[12] The application of biomimicry in bioprinting involves creating both identical cellular and extracellular parts of organs. For this approach to be successful, the tissues must be replicated on a micro scale. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the microenvironment, the nature of the biological forces in this microenvironment, the precise organization of functional and supporting cell types, solubility factors, and the composition of extracellular matrix.[11]

Autonomous self-assembly[]

The second approach of bioprinting is autonomous self-assembly. This approach relies on the physical process of embryonic organ development as a model to replicate the tissues of interest.[12] When cells are in their early development, they create their own extracellular matrix building block, the proper cell signaling, and independent arrangement and patterning to provide the required biological functions and micro-architecture.[11] Autonomous self-assembly demands specific information about the developmental techniques of the tissues and organs of the embryo.[12] There is a "scaffold-free" model that uses self-assembling spheroids that subjects to fusion and cell arrangement to resemble evolving tissues. Autonomous self-assembly depends on the cell as the fundamental driver of histogenesis, guiding the building blocks, structural and functional properties of these tissues. It demands a deeper understanding of how embryonic tissues mechanisms develop as well as the microenvironment surrounded to create the bioprinted tissues.[11]

Mini-tissue[]

The third approach of bioprinting is a combination of both the biomimicry and self-assembly approaches, which is called mini tissues. Organs and tissues are built from very small functional components. Mini-tissue approach takes these small pieces and manufacture and arrange them into larger framework.[12][11]

Printers[]

Akin to ordinary ink printers, bioprinters have three major components to them. These are the hardware used, the type of bio-ink, and the material it is printed on (biomaterials).[5] "Bio-ink is a material made from living cells that behaves much like a liquid, allowing people to 'print' it in order to create the desired shape. To make bio-ink, scientists create a slurry of cells that can be loaded into a cartridge and inserted into a specially designed printer, along with another cartridge containing a gel known as bio-paper."[13] In bioprinting, there are three major types of printers that have been used. These are inkjet, laser-assisted, and extrusion printers. Inkjet printers are mainly used in bioprinting for fast and large-scale products. One type of inkjet printer, called drop-on-demand inkjet printer, prints materials in exact amounts, minimizing cost and waste.[14] Printers that utilize lasers provide high-resolution printing; however, these printers are often expensive. Extrusion printers print cells layer-by-layer, just like 3D printing to create 3D constructs. In addition to just cells, extrusion printers may also use hydrogels infused with cells.[5]

Extrusion-Based Methods[]

Extrusion-based printing is a very common technique within the field of 3D printing which entails extruding, or forcing, a continuous stream of melted solid material or viscous liquid through a sort of orifice, often a nozzle or syringe.[15] When it comes to extrusion based bioprinting, there are three main type of extrusion. These are pneumatic driven, piston driven, and screw driven. Each extrusion methods have their own advantages and disadvantages. Pneumatic extrusion used pressurized air to force liquid bioink through a depositing agent. The air used to move the bioink must be free of contaminants. Air filters are commonly used to sterilize the air before it is used.[16] Piston driven extrusion utilizes a piston connected to a guide screw. The linear motion of the piston squeezes material out of the nozzle. Screw driven extrusion uses an auger screw to extrude material. The rotational motion forces the material down and out of the nozzle.[17] Screw driven devices allow for the use of higher viscosity materials and provide more volumetric control.[15] Once printed, many materials require a crosslinking step to achieve the desired mechanical properties for the construct, which can be achieved for example with the treatment of chemical agents or photo-crosslinkers.

Direct extrusion is one of the most common extrusion-based bioprinting techniques, wherein the pressurized force directs the bioink to flow out of the nozzle, and directly print the scaffold without any necessary casting.[18] The bioink itself for this approach can be a blend of polymer hydrogels, naturally derived materials such as collagen, and live cells suspended in the solution.[18] In this manner, scaffolds can be cultured post-print and not need further treatment for cellular seeding. Some focus in the use of direct printing techniques is based upon the use of coaxial nozzle assemblies, or coaxial extrusion. The coaxial nozzle setup enables the simultaneous extrusion of multiple material bioinks, capable of making multi-layered scaffolds in a single extrusion step.[19] The development of tubular structures has found the layered extrusion achieved via these techniques desirable for the radial variability in material characterization that it can offer, as the coaxial nozzle provides an inner and outer tube for bioink flow.[19] Indirect extrusion techniques for bioprinting rather require the printing of a base material of cell-laden hydrogels, but unlike direct extrusion contains a sacrificial hydrogel that can be trivially removed post-printing through thermal or chemical extraction.[20] The remaining resin solidifies and becomes the desired 3D-printed construct.

Other Printing Methods[]

Droplet-based bioprinting is a technique in which the bioink blend of cells and/or hydrogels are placed in droplets in precise positions. Most common amongst this approach are thermal and piezoelectric-drop-on-demand techniques.[21] Thermal technologies use short duration signals to heat the bioink, inducing the formation of small bubbles which are ejected. Piezoelectric bioprinting has short duration current rather applied to a piezoelectric actuator, which induces mechanical a vibration capable of ejecting a small globule of bioink through the nozzle. A significant aspect of the study of droplet-based approaches to bioprinting is accounting for mechanical and thermal stress cells within the bioink experience near the nozzle-tip as they are extruded.

Laser-based bioprinting can be distinguished between two major classes in general, those being based upon either cell transfer technologies or photo-polymerization. In cell transfer laser printing, a laser stimulates the interface between energy-absorbing material (e.g. gold, titanium, etc.) and the bioink, which contains a sacrificial material. This sacrificial ‘donor layer’ vaporizes under the laser’s irradiation, forming a bubble from the bioink layer which gets deposited from a jet.[22] Photo-polymerization techniques rather use photoinitiated reactions to solidify the ink, moving the beam path of a laser to induce the formation of a desired construct. Certain laser frequencies paired with photopolymerization reactions can be carried out without damaging cells laden into the material.

| Method of Bioprinting | Mode of Printing | Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Direct printing | Extrusion-based | Simple execution, no casting |

| Coaxial extrusion | Extrusion-based | Single step formation of multi-layered constructs |

| Indirect | Extrusion-based | Requires a removeable 'sacrificial material' to support structural formation |

| Laser | Laser-based | No shear stress upon cells suspended in ink |

| Droplet | Droplet-based | Precise control over flow & formation of scaffold |

Applications[]

Transplantable organs and organs for research[]

There are several applications for 3D bioprinting in the medical field. An infant patient with a rare respiratory disease known as tracheobronchomalacia (TBM) was given a tracheal splint that was created with 3D printing.[23] 3D bioprinting can be used to reconstruct tissue from various regions of the body. Patients with end-stage bladder disease can be treated by using engineered bladder tissues to rebuild the damaged organ.[24] This technology can also potentially be applied to bone, skin, cartilage and muscle tissue.[25] Though one long-term goal of 3D bioprinting technology is to reconstruct an entire organ, there has been little success in printing fully functional organs.[26] Unlike implantable stents, organs have complex shapes and are significantly harder to bioprint. A bioprinted heart, for example, must not only meet structural requirements, but also vascularization, mechanical load, and electrical signal propagation requirements.[27] Israeli researchers constructed a rabbit-sized heart out of human cells in 2019.[28]

Cultured meat[]

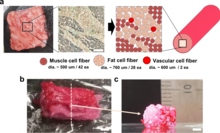

Bioprinting can also be used for cultured meat. In 2021, a steak-like cultured meat, composed of three types of bovine cell fibers was produced. The Wagyu-like beef has a structure similar to original meat.[29][30]

Impact[]

3D bioprinting contributes to significant advances in the medical field of tissue engineering by allowing for research to be done on innovative materials called biomaterials. Biomaterials are the materials adapted and used for printing three-dimensional objects. Some of the most notable bioengineered substances are usually stronger than the average bodily materials, including soft tissue and bone. These constituents can act as future substitutes, even improvements, for the original body materials. Alginate, for example, is an anionic polymer with many biomedical implications including feasibility, strong biocompatibility, low toxicity, and stronger structural ability in comparison to some of the body's structural material.[31] Synthetic hydrogels are also commonplace, including PV-based gels. The combination of acid with a UV-initiated PV-based cross-linker has been evaluated by the Wake Forest Institute of Medicine and determined to be a suitable biomaterial.[32] Engineers are also exploring other options such as printing micro-channels that can maximize the diffusion of nutrients and oxygen from neighboring tissues.[8] In addition, the Defense Threat Reduction Agency aims to print mini organs such as hearts, livers, and lungs as the potential to test new drugs more accurately and perhaps eliminate the need for testing in animals.[8]

See also[]

| Look up bioprinting in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- 3D printing § Bio-printing

- Cultured meat

- Ethics of bioprinting

- Magnetic 3D bioprinting

- Regenerative medicine

References[]

- ^ Roche CD, Brereton RJ, Ashton AW, Jackson C, Gentile C (2020). "Current challenges in three-dimensional bioprinting heart tissues for cardiac surgery". European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery. 58 (3): 500–510. doi:10.1093/ejcts/ezaa093. PMC 8456486. PMID 32391914.

- ^ Hinton TJ, Jallerat Q, Palchesko RN, Park JH, Grodzicki MS, Shue HJ, et al. (October 2015). "Three-dimensional printing of complex biological structures by freeform reversible embedding of suspended hydrogels". Science Advances. 1 (9): e1500758. Bibcode:2015SciA....1E0758H. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500758. PMC 4646826. PMID 26601312.

- ^ Roche CD, Sharma P, Ashton AW, Jackson C, Xue M, Gentile C (2021). "Printability, durability, contractility and vascular network formation in 3D bioprinted cardiac endothelial cells using alginate–gelatin hydrogels". Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology. 9: 110. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2021.636257. PMC 7968457. PMID 33748085.

- ^ Nakashima Y, Okazak K, Nakayama K, Okada S, Mizu-uchi H (January 2017). "Bone and Joint Diseases in Present and Future". Fukuoka Igaku Zasshi = Hukuoka Acta Medica. 108 (1): 1–7. PMID 29226660.

- ^ a b c d e Shafiee A, Atala A (March 2016). "Printing Technologies for Medical Applications". Trends in Molecular Medicine. 22 (3): 254–265. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2016.01.003. PMID 26856235.

- ^ a b Ozbolat IT (July 2015). "Bioprinting scale-up tissue and organ constructs for transplantation". Trends in Biotechnology. 33 (7): 395–400. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.04.005. PMID 25978871.

- ^ a b c Chua CK, Yeong WY (2015). Bioprinting: Principles and Applications. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. ISBN 9789814612104.

- ^ a b c Cooper-White M (1 March 2015). "How 3D Printing Could End The Deadly Shortage Of Donor Organs". Huffpost Science. TheHuffingtonPost.com, Inc. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ a b Harmon K (2013). "A sweet solution for replacing organs" (PDF). Scientific American. 308 (4): 54–55. Bibcode:2013SciAm.308d..54H. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0413-54. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-02-17. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ Singh D, Thomas D (April 2019). "Advances in medical polymer technology towards the panacea of complex 3D tissue and organ manufacture". American Journal of Surgery. 217 (4): 807–808. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2018.05.012. PMID 29803500.

- ^ a b c d e Murphy SV, Atala A (August 2014). "3D bioprinting of tissues and organs". Nature Biotechnology. 32 (8): 773–85. doi:10.1038/nbt.2958. PMID 25093879. S2CID 22826340.

- ^ a b c d Yoo J, Atala A (2015). "Bio-printing: 3D printing comes to life". ProQuest 1678889578. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Manappallil JJ (2015). Basic Dental Materials. JP Medical Ltd. ISBN 9789352500482.

- ^ "3D Printing Technology At The Service Of Health". healthyeve. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2016.

- ^ a b Lepowsky E, Muradoglu M, Tasoglu S (2018). "Towards preserving post-printing cell viability and improving the resolution: Past, present, and future of 3D bioprinting theory" (PDF). Bioprinting. 11: e00034. doi:10.1016/j.bprint.2018.e00034. ISSN 2405-8866 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ Gu Z, Fu J, Lin H, He Y (September 2020). "Development of 3D bioprinting: From printing methods to biomedical applications". Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 15 (5): 529–557. doi:10.1016/j.ajps.2019.11.003. PMC 7610207. PMID 33193859.

- ^ Derakhshanfar S, Mbeleck R, Xu K, Zhang X, Zhong W, Xing M (June 2018). "3D bioprinting for biomedical devices and tissue engineering: A review of recent trends and advances". Bioactive Materials. 3 (2): 144–156. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2017.11.008. PMC 5935777. PMID 29744452.

- ^ a b Datta, Pallab; Ayan, Bugra; Ozbolat, Ibrahim T. (March 2017). "Bioprinting for vascular and vascularized tissue biofabrication". Acta Biomaterialia. 51: 1–20. doi:10.1016/j.actbio.2017.01.035. ISSN 1742-7061.

- ^ a b Gupta, Prerak; Mandal, Biman B. (2021-06-12). "Tissue‐Engineered Vascular Grafts: Emerging Trends and Technologies". Advanced Functional Materials. 31 (33): 2100027. doi:10.1002/adfm.202100027. ISSN 1616-301X.

- ^ Hinton, Thomas J.; Jallerat, Quentin; Palchesko, Rachelle N.; Park, Joon Hyung; Grodzicki, Martin S.; Shue, Hao-Jan; Ramadan, Mohamed H.; Hudson, Andrew R.; Feinberg, Adam W. (2015-10-30). "Three-dimensional printing of complex biological structures by freeform reversible embedding of suspended hydrogels". Science Advances. 1 (9): e1500758. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1500758. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 4646826. PMID 26601312.

- ^ Munaz, Ahmed; Vadivelu, Raja K.; St. John, James; Barton, Matthew; Kamble, Harshad; Nguyen, Nam-Trung (March 2016). "Three-dimensional printing of biological matters". Journal of Science: Advanced Materials and Devices. 1 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1016/j.jsamd.2016.04.001. ISSN 2468-2179.

- ^ Devillard, Raphaël; Pagès, Emeline; Correa, Manuela Medina; Kériquel, Virginie; Rémy, Murielle; Kalisky, Jérôme; Ali, Muhammad; Guillotin, Bertrand; Guillemot, Fabien (2014), "Cell Patterning by Laser-Assisted Bioprinting", Methods in Cell Biology, Elsevier, 119, pp. 159–174, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-416742-1.00009-3, ISBN 978-0-12-416742-1, retrieved 2021-10-27

- ^ Zopf DA, Hollister SJ, Nelson ME, Ohye RG, Green GE (May 2013). "Bioresorbable airway splint created with a three-dimensional printer". The New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (21): 2043–5. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1206319. PMID 23697530.

- ^ Atala A, Bauer SB, Soker S, Yoo JJ, Retik AB (April 2006). "Tissue-engineered autologous bladders for patients needing cystoplasty". Lancet. 367 (9518): 1241–6. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68438-9. PMID 16631879. S2CID 17892321.

- ^ Hong N, Yang GH, Lee J, Kim G (January 2018). "3D bioprinting and its in vivo applications". Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 106 (1): 444–459. doi:10.1002/jbm.b.33826. PMID 28106947.

- ^ Sommer AC, Blumenthal EZ (September 2019). "Implementations of 3D printing in ophthalmology". Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 257 (9): 1815–1822. doi:10.1007/s00417-019-04312-3. PMID 30993457. S2CID 116884575.

- ^ Cui H, Miao S, Esworthy T, Zhou X, Lee SJ, Liu C, et al. (July 2018). "3D bioprinting for cardiovascular regeneration and pharmacology". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 132: 252–269. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2018.07.014. PMC 6226324. PMID 30053441.

- ^ Freeman D (April 19, 2019). "Israeli scientists create world's first 3D-printed heart using human cells". NBC News. Retrieved 2019-04-20.

- ^ "Japanese scientists produce first 3D-bioprinted, marbled Wagyu beef". New Atlas. 25 August 2021. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- ^ Kang DH, Louis F, Liu H, Shimoda H, Nishiyama Y, Nozawa H, et al. (August 2021). "Engineered whole cut meat-like tissue by the assembly of cell fibers using tendon-gel integrated bioprinting". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 5059. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-25236-9. PMC 8385070. PMID 34429413.

- ^ Crawford M (May 2013). "Creating Valve Tissue Using 3-D Bioprinting". ASME.org. American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ Murphy SV, Skardal A, Atala A (January 2013). "Evaluation of hydrogels for bio-printing applications". Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. Part A. 101 (1): 272–84. doi:10.1002/jbm.a.34326. PMID 22941807.

Further reading[]

- Tran J (2015). "To Bioprint or Not to Bioprint". North Carolina Journal of Law and Technology. 17: 123–78. SSRN 2562952. Archived from the original on 2019-03-10. Retrieved 2019-01-12.

- Tran J (May 7, 2015). "Patenting Bioprinting". Harvard Journal of Law and Technology Digest. 29. SSRN 2603693.

- Vishwakarma A (2014-11-27). Stem Cell Biology and Tissue Engineering in Dental Sciences. Elsevier, 2014. ISBN 9780123971579.

- 3D printing

- Biomaterials

- Tissue engineering

- Synthetic biology

- Self-replication