89th Guards Rifle Division

| 89th Guards Rifle Division | |

|---|---|

89th Guards Rifle Division troops in Belgorod 5 August 1943 | |

| Active | 1943–1945 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Division |

| Role | Infantry |

| Engagements | Battle of Kursk Operation Roland Belgorod–Kharkov Offensive Operation Battle of the Dniepr Battle of Korsun–Cherkassy Uman–Botoșani Offensive First Jassy–Kishinev Offensive Second Jassy–Kishinev Offensive Vistula-Oder Offensive Battle of the Seelow Heights Battle of Berlin |

| Decorations | |

| Battle honours | Belgorod Kharkov |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Col. Aleksei Ivanovich Baksov Maj. Gen. Mikhail Petrovich Seryugin Col. Ivan Alekseevich Pigin |

The 89th Guards Rifle Division was reformed as an elite infantry division of the Red Army in April 1943, based on the 1940 formation of the 160th Rifle Division, and served in that role until after the end of the Great Patriotic War. It would fight its way into the heart of Berlin prior to the German surrender.

The 160th had distinguished itself in Operation Little Saturn and the subsequent Ostrogozhsk–Rossosh Offensive and despite being partly destroyed during the German counteroffensive that retook Kharkov in March 1943 it was deemed worthy of Guards status. This redesignation also ended the situation where two divisions bearing the number 160th had been serving concurrently for 18 months. At the start of the Battle of Kursk the 89th Guards was in Voronezh Front on the far left flank of 6th Guards Army in reserve but during the fighting was transferred to the of 69th Army. When the Red Army went over to the offensive in early August the division was awarded one of the first honorifics for its part in the liberation of Belgorod and within weeks a further battle honor for helping to retake Kharkov. It then joined the summer offensive through eastern Ukraine to the Dniepr River where more than two dozen of its personnel became Heroes of the Soviet Union as a result of crossing operations near Kremenchug. Through the winter it would take part in the battles in the great bend of the Dniepr, now as part of the 37th Army of 2nd Ukrainian Front. During the advance through western Ukraine in the spring of 1944 to the Dniestr River the division was transferred to 53rd Army, still in 2nd Ukrainian Front, but the Front's first effort to penetrate into Moldavia was stymied. The second effort in August was a major victory and the 273rd Guards Rifle Regiment would be awarded an honorific. Following this the 89th Guards was transferred to the 5th Shock Army where it mostly served in the for the duration of the war. Prior to the Vistula-Oder Offensive that Army was itself transferred to 1st Belorussian Front. In early February the division helped to expand a bridgehead over the Oder River near Küstrin and remained in that position until the final offensive on Berlin began in mid-April. The division and its units collected further honors during this offensive and ended the war in the center of the city. In November 1945 it began reorganizing as the 23rd Guards Mechanized Division but this short-lived formation was disbanded near Moscow in March 1947.

Formation[]

Following its disastrous battle with the SS Panzer Corps east of Krasnograd the remnants of the 160th fell back farther to the east in late March 1943, coming under the command of 69th Army in Voronezh Front.[1] On April 18 it was officially redesignated as the 89th Guards Rifle Division; it would receive its Guards banner on May 11. Once the division completed its reorganization its order of battle was as follows:

- 267th Guards Rifle Regiment (from 443rd Rifle Regiment)

- 270th Guards Rifle Regiment (from 537th Rifle Regiment)

- 273rd Guards Rifle Regiment (from 636th Rifle Regiment)

- 196th Guards Artillery Regiment (from 566th Artillery Regiment)[2]

- 98th Guards Antitank Battalion (later 98th Guards Self-Propelled Artillery Battalion)

- 91st Guards Reconnaissance Company

- 104th Guards Sapper Battalion

- 158th Guards Signal Battalion (later 6th Guards Signal Company, then again 158th Guards Signal Battalion)

- 94th Guards Medical/Sanitation Battalion

- 93rd Guards Chemical Defense (Anti-gas) Company

- 95th Guards Motor Transport Company

- 92nd Guards Field Bakery

- 96th Guards Divisional Veterinary Hospital

- 519th Field Postal Station (later 52500th Field Postal Station)

- 437th Field Office of the State Bank

The division remained under the command of Col. Mikhail Petrovich Seryugin, who had just returned from the hospital after being wounded in February while commanding the division.[3][4] Deputy division commander Col. Aleksei Ivanovich Baksov, who had been acting commander of the 160th, was appointed to command of the 67th Guards Rifle Division on June 1; he would later be made a Hero of the Soviet Union and command the . At this time the 89th was a separate rifle division in 6th Guards Army of Voronezh Front,[5] still rebuilding from its losses in the spring.[6]

Battle of Kursk[]

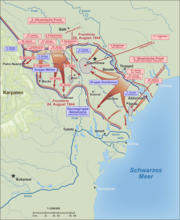

Once the STAVKA had decided to defend the Kursk salient against a German offensive detailed plans were put in place for a defense in depth. Specific attention was paid to guarding the boundaries between the Soviet fronts and armies with backing forces. Of particular concern was the junction of Voronezh Front's 6th and 7th Guards Armies northeast of Belgorod. Initially the 73rd Guards and 375th Rifle Divisions were placed on the forward edge with the 89th and 81st Guards Rifle Divisions in second echelon.[7] On May 5 the 81st Guards, which was numerically stronger, was moved forward to take up the positions of the 73rd Guards around Staryi Gorod, the "old town" of Belgorod on the east bank of the Northern Donets River.[8] The 89th Guards, which was still understrength from the March battles and was not fully recovered when the German offensive began, remained in second echelon in the vicinity of Melikhovo and Sabynino.[9]

The attack started at dawn on July 5. 6th Guards Army faced the 4th Panzer Army with II SS Panzer Corps on its right flank, and 7th Guards Army faced Army Detachment Kempf. The Front commander, Army Gen. N. F. Vatutin, was determined to prevent these two forces from linking up and driving to the northeast in the direction of Prokhorovka. The breakthrough operations in the first stage of the offensive proceeded with great difficulty; the 81st Guards in particular made a spirited defense. In order to stem the advance more decisively Vatutin proposed a counterattack to begin on July 8 and to involve the 89th Guards and several other forces, including the 2nd Guards Tank Corps, which received the following orders (in part) at 0050 hours:

... 2. The 2nd Guards Tank Corps will attack from the region of Petrovskii, Kriukovo, Chursino in the direction of Luchki from the northeast. Encircle and destroy the enemy, after which attack in the direction of Luchki, Gonki, and Bolkhovets... The 89th Guards Rifle Division will be attacking on your left, in the direction of Visloe and Erik, to emerge on the Erik – Shopino front, having in view a further offensive toward Belgorod... The attack will begin at 1030 8.07.43. Artillery preparation will continue for not more than 30 minutes.

2nd Guards Tanks had already been reduced from 216 tanks on July 5 to just 24 "runners" on July 8. Nevertheless a battalion of the 26th Guards Tank Brigade, a motorized rifle battalion of the 4th Guards Motorized Rifle Brigade, and elements of the 89th Guards forced a crossing of the Lipovyi Donets River in the area of Visloe and from the march conducted an attack in the direction of the Smelo k trudu Collective Farm and took Hill 209.5, but there it met with fire and counterattacks from up to 50 panzers. Bitter fighting continued for the rest of the day but the Soviet force was unable to advance further. During the evening a dispatch from 48th Rifle Corps to the headquarters of Voronezh Front noted that the German forces in the Luchki and Nechaevka areas were digging in and placing barbed-wire obstacles.[10]

Both sides regrouped during July 9 while German reconnaissance activity convinced General Vatutin that their next major blow would come on the Prokhorovka axis. Remaining aware of the importance of preventing Army Detachment Kempf from linking up with II SS Panzer Corps, at 1130 hours on July 10 he transferred a large number of his units, including the 89th Guards, to 69th Army, his backstop between 6th and 7th Guards Armies. This Army was ordered to hold along a line from Vasilevka to Shopino to Kiselevo to Myasoyedovo.[11] This order had been anticipated as far back as 0150 hours on July 9 when the 69th Army commander, Lt. Gen. V. D. Kryuchenkin, warned the commander of 48th Rifle Corps, Maj. Gen. Z. Z. Rogozny, that further forces would be arriving under his command.[12] The 375th Division's positions had been partly encircled due to the collapse of the 92nd Guards Rifle Division and it had to undertake a dangerous redeployment after dawn on July 10 which was covered by the fire of the 89th Guards. The 81st Guards was also falling back from its positions at Staryi Gorod toward a defensive line held by the division along the southern fringe of a wooded area northwest of Khokhlovo.[13]

Kryuchenkin decided on the night of July 10/11 to further regroup his forces and withdraw part of them from the dangerous sack that had formed as the result of the previous days' fighting in the area north of Belgorod. The sector from Visloe to Ternovka to Belomestnaya to Petropavlovka to Khokhlovo was turned over to the division and by morning it had occupied defensive positions between the Lipovyi and Severskii Donets along the front Kalinin–northern outskirts of Belomestnaya–Kiselevo.[14] In the orders issued to III Panzer Corps for that day the 168th Infantry Division was to cover the left flank of the Corps' assault wedge, overcome the line of the 89th Guards, and emerge in the depth of 48th Rifle Corps' defenses. Up to this point in the battle the division had suffered relatively few losses and was still fully combat-capable.[15] During the afternoon, following a series of repeated and unsuccessful attacks, the German division, with armor support from the 19th Panzer Division, managed to seize Khokhlovo and Kiselevo and pushed the outposts of the 89th Guards to the eastern bank of the Severskii Donets. After dusk these units crossed over to the river's western bank. During the day the main force of the III Panzer Corps, driving north from the Melikhovo area, broke through the 305th Rifle Division's front and by the onset of darkness had a significant force of tanks in the Verkhny Olshanets area, creating another dilemma for the 48th Corps.[16] Meanwhile a late-day counterattack by the 89th Guards, the 276th Guards Rifle Regiment of the 92nd Guards, and the 96th Guards Heavy Tank Brigade managed to retake most of Kiselevo.[17]

Breakthrough at Rzhavets[]

By the evening of July 11 it was clear to both sides that the grand German design for the Kursk offensive had failed. Their 9th Army on the northern shoulder of the salient had been stopped days earlier. II SS Panzer Corps was preparing for its major attack at Prokhorovka the next day. The commander of III Panzer Corps' 6th Panzer Division proposed a bold night-time foray to seize the village of Rzhavets on the Northern Donets deep within the positions of 69th Army as a last-ditch effort to link up with 4th Panzer Army. At 1900 hours the German VIII Air Corps delivered strikes on Kiselevo, Sabynino and the hamlet of Kisilev ordered by the commander of III Panzer Corps; at this time the headquarters of the 89th Guards was in Kisilev. A report from the division the next day describes the effects:

At 1900 more than 200 enemy bombers struck the combat formations and the headquarters of the division. During the attack on the command post the PNO-1 [assistant chief of operations] and the division commander's adjutant Popyk were severely wounded; four commanders were lightly wounded; three men were killed; and two light automobiles were burned.

Without any communications to 48th Corps or his neighboring units, Colonel Seryugin made a flawed decision and ordered his headquarters to be redeployed to the Novo-Oskochnoe area. This move was to be covered by the divisional training battalion under the command of Cpt. N. V. Riabtsev but en route in the darkness somewhere between Rzhavets and Kurakovka ran into the battlegroup of 6th Panzer Division moving in the opposite direction, led by tanks including Tigers of the 503rd Heavy Tank Battalion and followed by infantry in armored halftracks. While Seryugin had been confident that any tanks encountered would be Soviet the training battalion was forced to deploy for an uneven battle with hand grenades as the only effective weapon. The confusion was enhanced by the fact that the German force had placed a captured T-34 at the head of its column. In the heat of battle Seryugin lost his head and insisted on pushing on rather than backtracking. In consequence the 168th Infantry was able to force a crossing of the Northern Donets with a small force and captured Gostishchevo deep in the 48th Corps' defenses. General Vatutin later wrote:

Guards Colonel Seryugin, without establishing communications with his neighbors and the corps command... made an incorrect decision and voluntarily abandoned the line Kalinin–Kiselevo along the Northern Donets River, which was held by the 267th Guards Rifle Regiment.

The battlegroup of 6th Panzer proceeded to encircle Seryugin's small column and he ordered an all-round defense. Fighting lasted for several hours until his headquarters managed to escape on foot to Plota. From here it sent a dispatch to General Rogozny stating that two staff officers had been lost and that other losses among the divisions special units, which had been relocating with the headquarters, were being determined.[18]

Between them the German bridgeheads at Gostishchevo and Rzhavets put the entire 48th Rifle Corps under threat of encirclement. Even before midnight Rogozny and his staff began reorganizing his forces to meet the threat, as did higher headquarters up to the level of STAVKA. This was complicated by the fact that Voronezh Front had no available reserves. By 0500 hours on July 12 a large-scale retreat of forces was being noted along with signs of panic in certain units. General Kryuchenkin ordered the deployment of blocking detachments from his headquarters which during the day detained 2,842 men and stopped the incipient rout by 1600 hours. Full control over the situation would not be gained until July 16, after the divisions of 48th Rifle Corps had withdrawn to a new line of defense. Between July 12 and 17 a total of 386 men of the 89th Guards were detained by the blocking detachments.[19]

Operation Roland[]

By the end of the day on July 12 it was becoming clear that II SS Panzer Corps' attempt to take Prokhorovka had failed; Hitler would order Operation Citadel to cease the following day. In order to salvage something from the wreckage he authorized Field Marshal E. von Manstein's hastily-developed plan for Operation Roland, which would link up the SS Corps with III Panzer Corps to encircle and destroy at least the 48th Rifle Corps, if not all of 69th Army. The German forces spent most of July 13 regrouping for this new effort; however the III Panzers probed the Soviet defenses with strong reconnaissance forces and launched holding attacks from the area of Rzhavets. During the day the 89th Guards and one battalion of the 375th Rifle Division were subordinated to Maj. Gen. I. K. Morozov, the commander of the 81st Guards, in an effort to create a Corps reserve. A few hours later Morozov issued a formal rebuke to the chief of staff of the division for ordering the 267th Guards Regiment to fall back without his authorization, and the Regiment returned to its previous positions.[20]

The German intentions were generally understood by Kryuchenkin and he took measures to counter them but these largely involved the 92nd Guards and 305th Divisions, both of which had suffered heavy losses. Thus, in the area of III Panzer Corps' penetration a continuous line of defense could not be organized. Voronezh Front ordered a powerful artillery grouping to deploy at the disposal of 48th Corps to help cover this weakness. In addition, Vatutin issued orders for a preemptive counterattack to begin at 0500 hours on July 14 which would involve the 273rd Guards Rifle Regiment along with the 235th Guards Rifle Regiment of the 81st Guards, supported by two companies of the 26th Tank Brigade, to break through and retake Shcholokovo, but this was unsuccessful. The divisions of 48th Corps (81st, 89th, 93rd Guards and 375th Rifle Divisions) were simply exhausted from the fighting of the past week.[21]

Meanwhile the 2nd Guards Tank Corps and , guarding the northwestern shoulder of the salient held by 48th Corps, were struck by the 2nd SS Panzergrenadier Division Das Reich and the 167th Infantry Division. 2nd Guards Tanks had been partly restored to a total of 80 operational vehicles but both Soviet units, along with the right flank of the 375th Division, were forced to fall back under the combined pressure beginning around 1640 hours; the 375th was successful in halting the drive along most of its sector but eventually found itself attacked from three sides. On the opposite side of the salient the 69th Army reported a breakthrough by 50 German tanks, including 10 Tigers, and up to a battalion of infantry, in the direction of Avdeevka at 0815 hours. At 1900 the Army reported that this advance had been stopped near Avdeevka by the 92nd Guards assisted by the 11th and 12th Mechanized Rifle Brigades.[22]

By the end of July 14 the situation of 48th Rifle Corps had become critical, with its communications disrupted and ammunition in short supply. Kryuchenkin sent a special command group to Plota at 2000 hours with orders to, among other measures, "deploy no less than two artillery battalions of the 89th Guards Rifle Division in Kleimenovo." Despite this effort the 26th Guards Tank Brigade reported on the morning of July 15 that the encirclement was nearly complete, that Kleimenovo and other positions had already fallen, and German tanks had captured Maloyablonovo and Plota by 0850 hours. As the Voronezh and Steppe Fronts prepared to go over to the counteroffensive the retention of the salient was highly desirable as a springboard, but the 69th and 5th Guards Tank Armies no longer had the strength to do so. A few minutes later Vatutin issued his Order No. 248 demanding the recapture of Shakhovo in the heart of the salient by the 89th and 93rd Guards, the 375th, and elements of 5th Guards Tanks, but this was intended as a preliminary measure before the 48th Corps would be ordered back to a line that included Maloyablonovo at the base of the salient.[23]

Vatutin's order was soon superseded due to increasing German pressure and the realization that the closing pocket had to be evacuated quickly. General Rogozny issued verbal orders to Morozov at 0140 hours on July 15 to pull out during the predawn darkness. 48th Rifle Corps was led by the 89th Guards, followed in turn by 81st and 93rd Guards with the 375th Division bringing up the rear. The 89th Guards was likely clear of the pocket by 0400. Colonel Seryugin reported that the division had started to move into a new defensive line from Iamki to Gridino to Pokrovka to Kuzminka by 0700. Rogozny stated at 1040 hours that "The division had no losses. The withdrawal was completed under conditions of darkness in complete order." This positive report must be balanced against the figures for the fighting from July 10-16. From a starting strength of 8,355 personnel the division lost 106 killed, 312 wounded, 10 sick and 3,170 missing, or 43 percent of its manpower, although a portion of the missing would be eventually rounded up and returned to duty.[24] On July 15 the II SS Panzer Corps went over to the defensive across its entire front.

Into Eastern Ukraine[]

Later in July the 69th Army was transferred to Steppe Front; the 89th Guards remained in 48th Corps along with the 305th and 375th Rifle Divisions.[25] In preparation for the counteroffensive into Ukraine, Operation Polkovodets Rumyantsev, the commander of the Front, Col. Gen. I. S. Konev, formed a shock group consisting of the 53rd Army and the 48th Corps to attack on August 3 on a 11km front from Glushinskii to Visloe. 48th Corps, which had the 183rd Rifle Division added to its forces just before the attack, was to break through the German defense and, developing the offensive in the general direction of Belgorod, was to reach a line from Zagotskot to Belomestnaya on the first day. The 89th Guards, in conjunction with part of the forces of 35th Guards Corps, was to encircle and defeat the German forces in the Dacha area (east of Visloe) by the end of the operation's third day. The 48th Corps was organized in a single echelon and was backed by a tank brigade.[26] The offensive proceeded largely according to plan, and on August 4 the STAVKA tasked Steppe Front with the liberation of Belgorod, which Konev assigned to 69th and 7th Guards Armies. The German forces had transformed the city into a powerful center of resistance with a ring-shaped defense line built during the winter of 1941-42 and a large number of other engineering works including extensive minefields. It was defended by units of the 198th Infantry Division reinforced by artillery, mortars and tanks. Nevertheless on the morning of August 5 the 89th Guards and the 305th Rifle Divisions fought through the northern outskirts and began fierce street fighting in the city. The assault was joined by the 111th Rifle Division and elements of the from the east. By 1800 hours Belgorod was completely cleared of German forces.[27] The division was rewarded with one of the first honorifics presented by the STAVKA:

BELGOROD – ...89th Guards Rifle Division (Col. Seryugin, Mikhail Petrovich)... The troops that participated in the liberation of Belgorod, by order of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of 5 August 1943 and a commendation in Moscow, are given a salute of 12 artillery salvoes of 120 guns."[28]

Following this victory the offensive continued in the direction of Kharkov. On August 13 forces of Steppe Front broke through the external defensive line that the German command had prepared around the city and by the 17th fighting had begun in its northern outskirts.[29] By this time the division, along with its 48th Corps, had been transferred to 53rd Army and it was under these commands when it broke into the center of the city with the and linked up with the 183rd Division at Dzerzhinsky Square, marking the final liberation of Kharkov and earning it a second honorific:

KHARKOV – ...89th Guards Rifle Division (Col. Seryugin, Mikhail Petrovich)... The troops that participated in the liberation of Kharkov, by order of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of 23 August 1943 and a commendation in Moscow, are given a salute of 20 artillery salvoes of 224 guns."[30]

Battle of the Dniepr[]

Colonel Seryugin was promoted to the rank of major general on September 1. As of the same date the 89th Guards had returned to 69th Army as a separate division,[31] but on September 24 as Steppe Front advanced through eastern Ukraine the division was reassigned to the 82nd Rifle Corps of 37th Army which had been added to the Front from the Reserve of the Supreme High Command. This Army consisted of seven rifle divisions of which the 89th Guards was by far the weakest. As of September 25 it had 3,864 personnel, equipped with 197 light and 51 heavy machine guns; 48 82mm and 14 120mm mortars; 21 45mm antitank guns; nine 76mm regimental and 16 field guns and only two 122mm howitzers. The Army was in second echelon and was intended to relieve 69th Army and force the Dniepr along a line from Uspenskoye to Kutsevolovka in the center of the Front's offensive sector.[32]

The commander of 37th Army, Lt. Gen. M. N. Sharokhin, issued orders at 2100 hours on September 24 that the 82nd Corps was to concentrate by the morning of the 27th in the area Maloye Pereshchepino–Drabinovka–Petrovka. The Army was poorly supplied with crossing equipment and would rely on reinforcements of two mechanized pontoon bridge battalions, an engineer-sapper brigade and 48 wooden boats, but these were lagging behind the advance due to fuel shortages. Late on September 25 Sharokhin chose a sector from Uspenskoye to Myshuryn Rih, roughly 40km southeast of Kremenchuk, as his crossing point. The 57th Rifle Corps, plus the 89th Guards, would be in the first echelon with the remaining divisions of 82nd Corps in second; ideally the first echelon would force the river from the march. 89th Guards was to pursue the retreating German forces in the general direction of Aleksandrova and Pavlovka, reach the Dniepr by the end of September 26 and establish a bridgehead northeast of Uspenskoye the following morning.[33]

Due to supply shortages, poor roads and lack of crossing means this plan soon had to be refined. The division was now ordered to reach the river by the end of September 28 along the Gaponovka–Koleberda sector and force its crossing there. It was to be reinforced with two companies from the 43rd Tank Regiment, the 1851st Antitank Artillery Regiment and one battalion of Guards Mortars. However the leading formations in the Army's crossing operation would be the 57th Corps' 62nd Guards and 92nd Guards Rifle Divisions. While most crossing activity would take place under cover of darkness Sharokhin provided for the use of smoke-making equipment during daylight. His Army faced roughly 4,500 men of the German 8th Army's 39th and 106th Infantry Divisions, some of whom were still filtering across the river, as well as elements of 8th SS Cavalry Division Florian Geyer.[34]

In the initial crossing attempts the 62nd Guards' forward detachments were able to seize two small bridgeheads while the 92nd Guards failed and had to prepare a renewed effort. The 89th Guards was still closing to the river against rearguards of the 39th and 106th Infantry while elements of the 23rd Panzer Division began arriving in the Myshuryn Rih area on the west bank. The main goal of 37th Army on September 29-30 was to expand the existing bridgeheads, consolidate them, and repel increasingly powerful counterattacks. Overnight on September 28/29 the 110th Guards Rifle Division was committed from the Corps' second echelon. The 89th Guards was now ordered to force the river north of Koleberda and occupy a line from Uspenskoye to Height 140.3. However, throughout the day the division was unable to set about making its crossing. Apart from improvised means that were being gathered, including 18 rafts under construction, there were only three A-3 boats and four small inflatable boats available to it. With all this it was only possible to lift two platoons with weapons on a single trip. Nevertheless the forcing operation began at 2000 hours as one battalion of the 267th Guards Regiment secretly reached the right bank and established a foothold in the area of Lake Chervyakovo-Rechitse. By midnight two rifle companies were in the bridgehead as the division's remaining units took up jumping-off positions.[35]

One of the first men over was Sen. Sgt. Ivan Ivanovich Bakharev, who commanded a reconnaissance squad of the 267th Guards Regiment. He and his men landed near Koleberda and, using submachine guns, hand and antitank grenades, captured a German trench and a pair of machine guns. During the morning the squad linked up with rifle troops of the Regiment and in the fighting to expand the bridgehead Bakharev accounted for about 25 German soldiers killed or wounded. That afternoon he was killed by machine gun fire while attempting to destroy a German tank that he had already immobilized. On December 20 he would be posthumously made a Hero of the Soviet Union, one of 25 men of the division so honored for their roles in the Dniepr crossing.[36]

Fighting for Uspenskoye[]

By this time the division had been detached from 82nd Corps and was acting as a separate division in 37th Army.[37] By the morning of September 30 it had crossed the main forces of its rifle regiments to the west bank, but crossings were halted at dawn due to powerful German artillery strikes. As a result the 196th Guards Artillery was forced to continue its supporting fire from the east bank. During the day the rifle regiments managed to repel several German counterattacks and advance between 500m-1,000m. Altogether the bridgehead in the Uspenskoye area jointly held by the 89th and 92nd Guards was 5-6km wide and 3-4km in depth. The German defenses were being further reinforced on the Army's front by the Panzergrenadier Division Großdeutschland southeast of Myshuryn Rih and elements of 3rd SS Panzer Division Totenkopf. For October 1 General Sharokhin was determined to link up his separated bridgeheads and ordered the division to finally take and hold Uspenskoye. It encountered stubborn resistance, failed to advance and was then forced to repel counterattacks along its previous line. Meanwhile the divisional artillery continued crossing to the west bank through the day.[38]

The struggle for Uspenskoye continued on October 2, with little progress being made. Sharokhin planned to unite the divided bridgeheads held by the 89th Guards and the 57th Corps the following day, but this was overruled by Konev who was concerned with a crisis facing the right flank of 7th Guards Army to 37th Army's south. The 6th Panzer Division had now arrived in the Myshuryn Rih area while the 89th Guards continued the inconclusive fighting for Uspenskoye. During October 4 the Soviet buildup on the west bank continued with the 188th Rifle Division and the 1st Mechanized Corps' main forces getting across as the Front's support elements and supply echelons closed on the river. Sharokhin now had a nearly 2:1 advantage over the defenders in manpower and artillery although the German advantage in armor was close to 2.5:1. At this time the question arose of reconsidering the missions of the 89th and 92nd Guards Divisions. Their bridgeheads were still shallow and their initial tasks of tying down the 39th, 106th, and Totenkopf divisions had been fulfilled; in addition, the German strongpoints at Uspenskoye and Deriivka would not be taken by frontal attacks without unacceptable losses. Accordingly on the night of October 4/5 the 92nd Guards, leaving behind a small covering force, was evacuated to the east bank, and the 89th Guards was similarly withdrawn 24 hours later; both divisions then recrossed the Dniepr to the Army's main bridgehead near Myshuryn Rih. Uspenskoye was then transferred to the sector of 53rd Army. By 0500 hours on October 9 the division had concentrated in the area of Koshikov ravine–marker 144.1–Pertsev ravine. During the next day it became clear that the German forces were exhausted and Konev ordered the 5th Guards Army to enter the Myshuryn Rih bridgehead and expand it in preparation for a planned breakout by 5th Guards Tank Army in the direction of Piatykhatky.[39]

Into Western Ukraine[]

On the morning of October 15 a dozen rifle divisions attacked out of the bridgehead and that afternoon Konev committed the 5th Guards Tanks to the breakthrough. Over the next few days this advance tore open the left flank of the 1st Panzer Army and liberated Piatykhatky on the 18th, cutting the main railroads to Dnepropetrovsk and Kryvyi Rih.[40] At about this time the 89th Guards returned to the 82nd Corps, still in 37th Army of Steppe (as of October 20 the 2nd Ukrainian) Front.[41] The Front's forces pushed on to the latter city on October 21 and reached its outskirts on the 25th but came under counterattacks from XXXX Panzer Corps on October 27 which over the following three days badly damaged two mechanized corps and nine rifle divisions and forced the survivors to fall back roughly 32km.[42]

During November the 2nd Ukrainian Front was mostly engaged in clearing the west bank of the Dniepr and liberating the city of Cherkasy. This led to a battle of attrition into the third week of December which the Red Army could far more easily afford than the German and eventually led to a rupture of the front north of Kryvyi Rih.[43] The 89th Guards was again serving as a separate division in 37th Army in November,[44] but by the end of December it had been removed to the Front reserves.[45] On January 8, 1944 it was awarded the Order of the Red Banner for its part in the fighting for the west bank.[46]

Later that month the division left the Front reserves and was briefly returned to the 48th Rifle Corps, now in 53rd Army.[47] This Army was not directly involved in the encirclement battle around Korsun-Shevchenkovskii but advanced south of the pocket in the direction of Zlatopil. In February the division left 48th Corps and was again under direct Army control, but in March, during the Uman–Botoșani Offensive, it was assigned to the 26th Guards Rifle Corps.[48] The division would remain in this Corps for most of the rest of the war.[49]

Jassy–Kishinev Offensives[]

On March 31 the 53rd Army, under command of Lt. Gen. I. M. Managarov, conquered the city of Kotovsk before pressing on toward Dubăsari on the Dniestr River, 60km to the southwest. The Army was deployed with the 26th Guards Corps in the center, the 48th Corps on the left and the 49th Rifle Corps on the right. The 26th Guards Corps was led by Maj. Gen. P. A. Firsov and also had the 25th and 94th Guards Rifle Divisions under command. As the Army approached the river on April 4 the 25th Guards was detached to 49th Corps on the west bank to assist the 4th Guards Army in clearing XXXX Panzer Corps from the north bank of the Răut River in an effort to reach Chișinău.[50]

Meanwhile the 89th and 94th Guards, along with the three rifle divisions of 48th Corps, maintained constant pressure against the German forces defending the bridgehead on the Dniestr's east bank northeast of Dubăsari. Ultimately, by April 13 this pressure forced the 46th Infantry Division, , and the 4th Mountain Division back from their forward line to a new defensive line 8km to the rear from Hlinaia to Roghi. Facing this denser and more formidable line, and given the exhaustion of the 49th Corps and 4th Guards Army from the fighting along the Răut, Konev ordered the 53rd Army to go over to the defensive on April 18 although he gave Managarov permission to conduct local battles to improve his positions. In early May the STAVKA began planning for a renewed offensive on Chișinău with 53rd Army operating in cooperation with 3rd Ukrainian Front. While the 26th Guards Corps was to form the shock group for this effort,[51] the 89th Guards had been detached and was now again serving as a separate division within the Army.[52] In the event this plan was overtaken by German counterattacks south of Dubăsari beginning on May 10.[53]

From June 2 to July 5 General Seryugin temporarily commanded the 49th Rifle Corps during the hospitalization of its commander, Maj. Gen. G. N. Terentyev.[54] Col. Ivan Alekseevich Pigin, the deputy chief of staff of the 53rd Army for auxiliary command posts, took over command of the division in Seryugin's absence.[55] In June the division returned to 26th Guards Corps and in the third week of August it was transferred with its Corps to the 5th Shock Army in 3rd Ukrainian Front just prior to the start of the second Jassy–Kishinev offensive.[56][54] The division would remain in this Army for the duration of the war.[57]

Second Jassy-Kishinev Offensive[]

In the planning for this offensive the 5th Shock Army was initially to hold along its line from Brăviceni to Bender in preparation for a pursuit in the direction of Chișinău once its flanking armies forced a withdrawal of the German/Romanian forces along the Dniestr. The attack on the city would come from the 26th Guards Corps (89th and 94th Guards) from the north from the area between Orgeev and Piatra against Corps Detachment "F" on a 6km-wide front while the 32nd Rifle Corps advanced from the east. While the main offensive began on August 20 the 5th Shock did not go over to the attack until the 22nd, although its artillery, including that of the 196th Guards Artillery Regiment, fired in support of its Front from the outset.[58] In the event the operation unfolded largely according to plan. 5th Shock began its pursuit overnight on August 22/23 as the forces of German 6th Army that it had been facing began to fall back across the Prut River. By the end of the day 26th Rifle Corps, assisted by the 266th Rifle Division, reached Chișinău, enveloped it from the north and west and got involved in street fighting. At the same time the 32nd Rifle Corps reached the Bîc River, crossed it and cut the rail line from Chișinău to Bender. By 0400 hours the city had been cleared of Axis forces and the 26th Guards Corps continued its pursuit and reached the Botna River from Ulmu to Ruseștii Noi by the end of the day.[59] One of the 89th Guards' regiments was rewarded with a battle honor:

KISHINEV – ...273rd Guards Rifle Regiment (Lt. Col. Bunin, Vasilii Vasilevich)... The troops that participated in the liberation of Kishinev, by order of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief of 24 August 1944 and a commendation in Moscow, are given a salute of 24 artillery salvoes of 324 guns."[60]

The mission of 5th Shock Army now was to help complete the elimination of the 6th Army, which was largely encircled east of the Prut. The general advance was set for 0400 hours on August 25 but was spearheaded by one reinforced regiment from each division acting as a forward detachment overnight. The Army attacked in the direction of Cărpineni and the 26th Guards Corps, on the Army's right flank, reached a line from Boghiceni to Lăpușna, with its front facing southwest. During the day as many as 37,000 Axis officers and soldiers were attempting to escape from the pocket.[61]

By this time Romania had capitulated and its remaining forces were rapidly surrendering. 3rd Ukrainian Front's command ordered the German remnants trapped in the Kotovskoe area to be eliminated on August 26. During the day 5th Shock penetrated the German screening units and proceeded to round up scattered groups southeast of Cărpineni while linking up with the 57th Army. The following day the fighting on the Front's sector began to abate as thousands of exhausted and demoralized German soldiers surrendered and the Front's armies began to resolve new tasks.[62] While 5th Shock was still in the Front at the beginning of September, later that month it was removed to the Reserve of the Supreme High Command and in October was reassigned to the 1st Belorussian Front,[63] where it would remain for the duration. During this break from active operations the 98th Guards Antitank Battalion had its towed antitank guns replaced by 12 SU-76 vehicles, becoming the 98th Guards Self-Propelled Artillery Battalion. In order to help make up losses among its infantry the division had the 123rd Separate Rifle Company assigned to it directly.[64]

Into Poland and Germany[]

Upon joining its new Front the 5th Shock Army took up reserve positions west of Siedlce and northeast of the Front's bridgehead over the Vistula River at Magnuszew, south of Warsaw. In the planning for the Vistula-Oder offensive the Army was to enter the bridgehead prior to its start, attack on the first day and break through the German defense on a 6km-wide front along the Wybrowa–Stszirzina sector, supported by the artillery of the 2nd Guards Tank Army, and was then to develop the attack in the general direction of Branków and Goszczyn. Once the breakthrough was made the armor units and subunits in direct support of the Army's infantry were to unite as a mobile detachment to seize the second German defensive zone from the march with the goal of reaching the area of Bronisławów to Biała Rawska by the fourth day.[65]

The offensive began at 0855 hours on January 14, 1945 with a reconnaissance-in-force following a 25-minute artillery preparation by all the Front's artillery. On the 5th Shock's and 8th Guards Army's sectors this quickly captured 3-4 lines of German trenches. The main forces of these armies took advantage of this early success and began advancing behind a rolling barrage, gaining as much as 12-13km during the day and through the night before going over to the pursuit on January 15.[66] Two days later the 89th Guards took part in the liberation of the towns of Sochaczew, Skierniewice and Łowicz; in recognition of this on February 19 the 267th and 270th Guards Rifle Regiments would each receive the Order of the Red Banner.[67]

During January 18-19 the Front's mobile forces covered more than 100km while the combined-arms armies advanced 50-55km. On January 26 the Front commander, Marshal G. K. Zhukov, informed the STAVKA of his plans to continue the offensive. 5th Shock Army would attack in the general direction of Neudamm and then force the Oder River in the area of Alt Blessin before continuing to advance towards Nauen. On January 28 the 2nd Guards Tank and 5th Shock Armies broke through the Pomeranian Wall from the march and by the end of the month reached the Oder south of Küstrin and seized a bridgehead 12km in width and up to 3km deep. This would prove to be the limit of 5th Shock's advance until April.[68]

Battle of Berlin[]

On April 5 the 196th Guards Artillery Regiment was awarded the honorific "Brandenburg" for its part in the invasion of that historic German province and on the same date the 104th Guards Sapper Battalion and the 158th Guards Signal Battalion each received the Order of the Red Star for the same accomplishment.[69] At the start of the Berlin operation the 5th Shock was one of four combined-arms armies that made up the main shock group of 1st Belorussian Front. The Army deployed within the Küstrin bridgehead along a 9km-wide front between Letschin and Golzow and was to launch its main attack on its left wing on a 7km sector closer to the latter place. The 26th Guards Corps had the 94th Guards and 266th Divisions in the first echelon and the 89th Guards in the second, but the 94th Guards was not on the axis of the main attack. All three divisions had between 5,000 and 6,000 personnel on strength. The Army had an average of 43 tanks and self-propelled guns on each kilometre of the breakthrough front.[70]

In the days just before the offensive the 3rd Shock Army was secretly deployed into the bridgehead which required considerable regrouping and covering operations by elements of 5th Shock. The Army then occupied jumping-off positions for a reconnaissance-in-force by battalions of five of its divisions while the remainder carried out more regular reconnaissance activities beginning early on the morning of April 14. After a 10-minute artillery preparation the 89th Guards attacked with two battalions and in heavy fighting captured the first German trench and by the end of the day had consolidated in the area of marker 8.1. In the course of two days of limited fighting the Front's troops advanced as much as 5km, ascertained and partly disrupted the German defensive system, and had overcome the thickest zone of minefields. The German command was also misled as to when the main offensive would occur.[71]

In the event that offensive began on April 16. 5th Shock attacked at 0520 hours, following a 20-minute artillery preparation and with the aid of 36 searchlights. 26th Guards Corps advanced nearly 6km and during the night reached the east bank of the Alte Oder, which it forced at 1000 hours on April 17 following a powerful artillery barrage. This took it through the second defensive zone and the eastern branch of the intermediate position, reaching the southwest bank of the Dolgensee following an advance of 11km. As a whole the Army broke through all three positions of the main German defensive zone, reached the second defensive position, and captured 400 prisoners. The next day 5th Shock resumed its offensive at 0700 hours, following a 10-minute artillery preparation. The Corps, cooperating with the 1st Mechanized Corps and part of 12th Guards Tank Corps, advanced 3km, beat off three counterattacks of up to a battalion in strength supported by 10-20 tanks each, and by the end of the day had reached the western branch of the German second position along a front between Batzlow and Rigenwalde. During April 19 the 26th Guards Corps, still working with 12th Guards Tanks, completed the breakthrough of this position, then the third defensive zone and finally advanced a further 8km, ending the day along a line from Kensdorf Creek to height 111.1.[72]

On April 20 the Corps continued attacking to the west with two divisions in the first echelon. Bypassing Strausberg from the north it advanced 11km to the west with 12th Guards Tanks and penetrated Berlin's outer defensive line in the Wesendahl area by the day's end. The next day the 5th Shock broke into the clear and elements of 26th Guards Corps captured Strausberg in cooperation with 32nd Corps and by the end of the day had completely cleared Hohenschönhausen following an advance of 23km. During April 22 the Corps advanced up to 4km into the city and was fighting for Biesdorf. The next day it occupied the Silesian Station and the adjacent area in stubborn fighting following an advance of another 4km. On the same day General Seryugin left command of the 89th Guards; he would begin study at the Voroshilov Higher Military Academy in June and would be promoted to the rank of lieutenant general in March 1951. He was replaced on April 24 by Col. Georgii Yakovlevich Kolesnikov who had previously commanded the 49th Guards and 24th Guards Rifle Divisions. During April 26 the 26th Guards and 32nd Corps fought along the north bank of the Spree River, advancing in fighting about 600m and by the end of the day reached the Kaiserstrasse and Alexanderstrasse. During the next day the two corps, following furious fighting, were able to advance no more than 400-500m along a narrow 500m sector, and on April 28 managed to clear just several blocks.[73] But by now the German position in Berlin was much more than hopeless and the capitulation took place on May 2.

Postwar[]

When the fighting stopped the men and women of the division shared the full title of 89th Guards Rifle, Belgorod-Kharkov, Order of the Red Banner Division. [Russian: 89-я гвардейская стрелковая Белгородско-Харьковская Краснознамённая дивизия.] In a final round of awards on June 11 the division was awarded the Order of Suvorov, 2nd Degree, while the 273rd Guards Rifle Regiment was presented with the Order of the Red Banner, the 270th Guards Rifle Regiment received the Order of Suvorov, 3rd Degree, and the 196th Guards Artillery Regiment won the Order of Kutuzov, 3rd Degree, all for their parts in the capture of Berlin.[74] From early July the division came under the command of Maj. Gen. Vladimir Filippovich Stenin, who had previously led the . By now it was assigned to the Group of Soviet Forces in Germany. In November the 89th Guards began reorganizing as the 23rd Guards Mechanized Division; this short-lived formation was transferred to the Moscow Military District in 1946 where it was disbanded in March 1947.

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 87

- ^ Charles C. Sharp, "Red Guards", Soviet Guards Rifle and Airborne Units 1941 to 1945, Soviet Order of Battle World War II, Vol. IV, Nafziger, 1995, p. 80

- ^ Baksov & Ayollo 1943, p. 2.

- ^ Seryugin & Ayollo 1943, p. 2.

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 137

- ^ Valeriy Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, ed. & trans. S. Britton, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2011, p. 567

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, Kindle ed., book 1, pt. 1, ch. 2

- ^ Zamulin, The Forgotten Battle of the Kursk Salient, ed. & trans. S. Britton, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2018, p. 52

- ^ Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, p. 108

- ^ Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, pp. 138-40, 142-43, 153

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, Kindle ed., book 1, pt. 2, ch. 3

- ^ Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, p. 185

- ^ Zamulin, The Forgotten Battle of the Kursk Salient, pp. 451-52, 458

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, Kindle ed., book 1, pt. 2, ch. 3

- ^ Zamulin, The Forgotten Battle of the Kursk Salient, pp. 489-90

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, Kindle ed., book 1, pt. 2, ch. 3

- ^ Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, pp. 402-03

- ^ Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, pp. 403-07

- ^ Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, pp. 407-10, 487

- ^ Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, pp. 474, 499-500

- ^ Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, pp. 476-77, 482, 484-85

- ^ Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, pp. 488-89, 491, 493-95

- ^ Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, pp. 501-03

- ^ Zamulin, Demolishing the Myth, pp. 504-07, 511

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 195

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, Kindle ed., book 2, pt. 2, ch. 1

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, Kindle ed., book 2, pt. 2, ch. 2

- ^ http://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/1-ssr-1.html. In Russian. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of Kursk, Kindle ed., book 2, pt. 2, ch. 2

- ^ http://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/1-ssr-6.html. In Russian. Retrieved June 18, 2021.

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 224

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of The Dnepr, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2018, pp. 247, 249, 255

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of The Dnepr, pp. 249-51

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of The Dnepr, pp. 252-53, 263-64

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of The Dnepr, pp. 266-69

- ^ https://warheroes.ru/hero/hero.asp?Hero_id=16. In Russian; English translation available. Retrieved June 21, 2021.

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 252

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of The Dnepr, pp. 271-74

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Battle of The Dnepr, pp. 275-79, 283-84

- ^ Earl F. Ziemke, Stalingrad to Berlin, Center of Military History United States Army, Washington, DC, 1968, pp. 176, 181

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 280

- ^ Ziemke, Stalingrad to Berlin, pp. 183-84

- ^ Ziemke, Stalingrad to Berlin, pp. 187-89

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1943, p. 308

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 19

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967a, p. 249.

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 47

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, pp. 76, 107

- ^ Sharp, "Red Guards", p. 81

- ^ David M. Glantz, Red Storm Over the Balkans, University Press of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, 2007, pp. 78, 86-88

- ^ Glantz, Red Storm Over the Balkans, pp. 88-89, 285-86

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, p. 168

- ^ Glantz, Red Storm Over the Balkans, pp. 292-93

- ^ a b Tsapayev & Goremykin 2014, p. 390.

- ^ Tsapayev & Goremykin 2014, p. 12.

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, pp. 198, 262

- ^ Sharp, "Red Guards", p. 81

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Iasi-Kishinev Operation, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2017, pp. 44-45, 53, 56, 83

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Iasi-Kishinev Operation, pp. 121, 127

- ^ http://www.soldat.ru/spravka/freedom/1-ssr-3.html. In Russian. Retrieved June 28, 2021.

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Iasi-Kishinev Operation, pp. 135-36

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Iasi-Kishinev Operation, pp. 137-39, 141

- ^ Combat Composition of the Soviet Army, 1944, pp. 262, 299, 315

- ^ Sharp, "Red Guards", p. 81

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, pp. 40, 55, 573-74. Note that the 5th Shock is mistakenly identified as the 5th Guards Army on p. 573.

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, pp. 72-73

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, p. 230.

- ^ Soviet General Staff, Prelude to Berlin, pp. 76, 82, 589-90. Note this source misidentifies the Army as 5th Guards at one point on p. 82.

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, p. 66.

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, ed. & trans. R. W. Harrison, Helion & Co., Ltd., Solihull, UK, 2016, Kindle ed., ch. 11

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, Kindle ed., ch. 12

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, Kindle ed., ch. 12

- ^ Soviet General Staff, The Berlin Operation 1945, Kindle ed., ch. 15, 20

- ^ Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union 1967b, pp. 344–45, 349, 351.

Bibliography[]

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1967a). Сборник приказов РВСР, РВС СССР, НКО и Указов Президиума Верховного Совета СССР о награждении орденами СССР частей, соединениий и учреждений ВС СССР. Часть I. 1920 - 1944 гг [Collection of orders of the RVSR, RVS USSR and NKO on awarding orders to units, formations and establishments of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Part I. 1920–1944] (PDF) (in Russian). Moscow.

- Affairs Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1967b). Сборник приказов РВСР, РВС СССР, НКО и Указов Президиума Верховного Совета СССР о награждении орденами СССР частей, соединениий и учреждений ВС СССР. Часть II. 1945 – 1966 гг [Collection of orders of the RVSR, RVS USSR and NKO on awarding orders to units, formations and establishments of the Armed Forces of the USSR. Part II. 1945–1966] (in Russian). Moscow.

- Baksov, Colonel; Ayollo, Lieutenant Colonel (9 April 1943). "Боевой приказ штаба 160 сд" [Combat Order of the Headquarters of the 160th Rifle Division]. Pamyat Naroda (in Russian). Central Archives of the Russian Ministry of Defence. – Located in fond 1252, opus 1, file 15, list 107 of the Central Archives of the Russian Ministry of Defence

- Grylev, A. N. (1970). Перечень № 5. Стрелковых, горнострелковых, мотострелковых и моторизованных дивизии, входивших в состав Действующей армии в годы Великой Отечественной войны 1941-1945 гг [List (Perechen) No. 5: Rifle, Mountain Rifle, Motor Rifle and Motorized divisions, part of the active army during the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Voenizdat. p. 193

- Main Personnel Directorate of the Ministry of Defense of the Soviet Union (1964). Командование корпусного и дивизионного звена советских вооруженных сил периода Великой Отечественной войны 1941–1945 гг [Commanders of Corps and Divisions in the Great Patriotic War, 1941–1945] (in Russian). Moscow: Frunze Military Academy. pp. 181, 328

- Seryugin, Colonel; Ayollo, Lieutenant Colonel (9 April 1943). "Боевой приказ штаба 160 сд" [Combat Order of the Headquarters of the 160th Rifle Division]. Pamyat Naroda (in Russian). Central Archives of the Russian Ministry of Defence. – Located in fond 1252, opus 1, file 28, list 2 of the Central Archives of the Russian Ministry of Defence

- Tsapayev, D.A.; et al. (2014). Великая Отечественная: Комдивы. Военный биографический словарь [The Great Patriotic War: Division Commanders. Military Biographical Dictionary] (in Russian). 5. Moscow: Kuchkovo Pole. ISBN 978-5-9950-0457-8.

External links[]

- Infantry divisions of the Soviet Union in World War II

- Military units and formations established in 1943

- Military units and formations disestablished in 1945

- Military units and formations awarded the Order of the Red Banner

- 1943 establishments in the Soviet Union

- 1945 disestablishments in the Soviet Union