Aṣẹ

| Part of a series on |

| Yoruba religion (Òrìṣà-Ifá) |

|---|

|

Ase or ashe (from Yoruba àṣẹ)[1] is a Yoruba philosophical concept through which the Yoruba of Nigeria conceive the power to make things happen and produce change. It is given by Olodumare to everything — gods, ancestors, spirits, humans, animals, plants, rocks, rivers, and voiced words such as songs, prayers, praises, curses, or even everyday conversation. Existence, according to Yoruba thought, is dependent upon it.[2]

In addition to its sacred characteristics, ase also has important social ramifications, reflected in its translation as "power, authority, command." A person who, through training, experience, and initiation, learns how to use the essential life force of things to willfully effect change is called an alaase.

Rituals to invoke divine forces reflect this same concern for the autonomous ase of particular entities. The recognition of the uniqueness and autonomy of the ase of persons and gods is what structures society and its relationship with the other-world.[2]

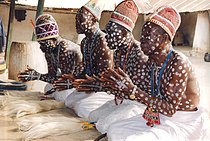

Ashe and Yoruba art[]

The concept of ashe influences how many of the Yoruba arts are composed. In the visual arts, a design may be segmented or seriate - a "discontinuous aggregate in which the units of the whole are discrete and share equal value with the other units."[3] Such elements can be seen in Ifá trays and bowls, veranda posts, carved doors, and ancestral masks.

Regarding composition in Yoruba art as a reflection of the concept of ashe, Drewal writes:

Units often have no prescribed order and are interchangeable. Attention to the discrete units of the whole produces a form which is multifocal, with shifts in perspective and proportion... Such compositions (whether representational or not) mirror a world order of structurally different yet autonomous elements. It is a formal means of organizing diverse powers, not only to acknowledge their autonomy but, more importantly, to evoke, invoke, and activate diverse forces, to marshal and bring them in to the phenomenal world. The significance of segmented composition in Yoruba art can be appreciated if one understands that art and ritual are integral to each other.[2]

The head as the site of ase[]

The head, or ori, is vested with great importance in Yoruba art and thought. When portrayed in sculpture, the size of the head is often represented as four or five times its normal size in relation to the body in order to convey that it is the site of a person's ase as well as his or her essential nature, or iwa.[2] The Yoruba distinguish between the exterior (ode) and inner (inu) head. Ode is the physical appearance of a person, which may either mask or reveal one's inner (inu) aspects. Inner qualities, such as patience and self-control, should dominate outer ones.

The head also links the person with the other-world. The imori ceremony (which translates to knowing-the-head) is the first rite that is performed after a Yoruba child is born. During imori, a diviner determines whether the child comes from his or her mother's or father's lineages or from a particular orisa. If the latter is the case, then the child will undergo an orisa initiation during adulthood, during which the person's ori inu becomes the spiritual vessel for that orisa's ase. To prepare for these ceremonies, the person's head is shaved, bathed and anointed.[2]

Modern usage in the diaspora[]

Since at least the time of the Afrocentrism movement in the Anglophone diaspora during the late 20th century, the term "Ashe" has become a relatively common term in the US, with the general connotation being of affirmation and hopeful wishes. It has also come to be used in the Black Christian religious context as an equivalent (or replacement) of the word "Amen."[4][5]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "What Is Ase Ire?". Ase Ire.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2018. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Drewal, H. J., and J. Pemberton III with Rowland Abiodun (1989). Allen Wardwell (ed.). Yoruba: Nine Centuries of African Art and Thought. New York City: The Center for African Art.

- ^ Drewal, M. T., and H. J. Drewal (1987). "Composing Time and Space in Yoruba Art". Word and Image: A Journal of Verbal/Visual Enquiry. 3 (3): 225–251. doi:10.1080/02666286.1987.10435383.

- ^ "Black Catholic History Month Installment 1. "The Gift-Ashe"". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

- ^ """Amen" and "Ashe": African American Protestant Worship and Its West African Ancestor" by Coleman, Will - Cross Currents, Vol. 52, Issue 2, Summer 2002".[dead link]

Further reading[]

- Bascom, W. R. 1960. "Yoruba Concepts of the Soul." In Men and Cultures. Edited by A. F. C. Wallace. Berkeley: University of California Press: 408.

- Prince, R. 1960. "Curse, Innovation and Mental Health among the Yoruba." Canadian Psychiatric Journal 5 (2): 66.

- Verger, P. 1864. "The Yoruba High God- A Review of the Sources." Paper presented at the Conference on the High God in Africa, University of Ife: 15–19.

- Ayoade, J. A. A. 1979. "The Concept of Inner Essence in Yoruba Traditional Medicine." In African Therapeutic Systems. Edited by Z. A. Ademuwagun, et al. Waltham, Mass.: Crossroad Press: 51.

- Fagg, W. B., and J. Permberton 3rd. 1982. Yoruba Sculpture of West Africa. New York: Alfred A. Knopf: 52ff.

- Drewal, M. T., and H. J. Drewal. 1983. Gelede: A Study of Art and Feminine Power Among the Yoruba. Bloomington: Indiana University Press: 5–6, 73ff.

- Jones, Omi Osun Joni L. 2015. Theatrical Jazz: Performance, Àse, and the Power of the Present Moment. Columbus: Ohio State University Press: 215–243.

- Yoruba words and phrases

- Yoruba culture

- Yoruba religion

- Yoruba art

- Nigerian art

- Energy (esotericism)

- Vitalism