Achan (biblical figure)

Achan (/ˈeɪkæn/; Hebrew: עכן), the son of Carmi, the son of Zabdi, the son of Zerah, of the tribe of Judah, is a figure who appears in the Book of Joshua in the Hebrew Bible in connection with the fall of Jericho and conquest of Ai.

His name is given as Achar in 1 Chronicles 2:7.

Account in the Book of Joshua[]

According to the narrative of Joshua chapter 7, Achan pillaged an ingot of gold, a quantity of silver, and a "beautiful Babylonian garment" from Jericho, in contravention of Joshua's directive that "all the silver, and gold, and vessels of brass and iron, are consecrated unto the Lord: they shall come into the treasury of the Lord" (Joshua 6:19).

Although the account suggests that Achan personally was guilty of coveting and taking these spoils, the chapter opens with a statement that the whole community of "the children of Israel [had] committed a trespass" (Joshua 7:1). For Achan's personal sin all the children of Israel suffered defeat in battle before Achan was found.

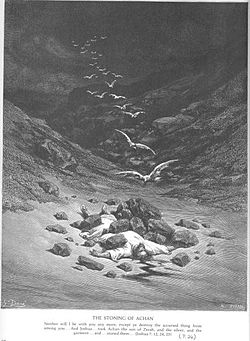

The Book of Joshua claims that this act resulted in the Israelites being collectively punished by God, in that they failed in their first attempt to capture Ai, with about 36 Israelitees lost (Joshua 7:5). The Israelites used cleromancy (the sacred Lots Urim and Thummim)[1] to decide who was to blame, and having identified Achan, stoned him, as well as his sheep, other livestock and his children to death. Their remains were burnt by the Israelites, according to the text, and stones piled on top.

Interpretation[]

The narrative states that the location for this punishment of Achan, which lies between Jericho and Ai, became known as the vale of Achor in memory of him. This narrative is probably an etiological myth providing a folk etymology for Achor,[2][3] at the point in the narrative where the vale of Achor is necessarily crossed.

One item to note however is that the text describes the garment that Achor stole as Babylonish; (from Shinar) the time of the Israelite invasion is usually dated to the 15th or 12th centuries BC, but between 1595 BCE and 627 BCE Babylon was under foreign rule. For this reason (what reason?), a few textual scholars[who?] believe that this part of the Achor narrative was written during the 7th century BC or later, but many Biblical scholars[who?] believe the judge Samuel may have put together this account from historical books from that time.

It is not certain, however, that the whole Achor narrative dates from this time, as textual critics believe that the Achor narrative may have been spliced together from two earlier source texts; the words in the first part of Joshua 7:25, "all Israel stoned him with stones" (וירגמו אתו) show a different style and tradition from those at the end of the verse: "and they burned them in fire, and they stoned them with stones" (וישרפו אתם באש ויסקלו אתם באבנים).[1] The repetition, the switching from "him" to "them", and switching of the Hebrew verb for "to stone", indicate that this story may be an amalgam from two different sources.[1][3]

Rabbinic[]

Rashi argues that the stoning was only carried out on the livestock and Achan himself, and that his children were merely brought forward to witness the Israelites ... stone them (Biblical text with emphasis added). One tradition that is reported by the Classical Rabbinical literature,[citation needed] states that Achan's crime was far worse than the Biblical account appears—Achan had, according to these Rabbis, also stolen a magic idol with a golden tongue, silver votive gifts dedicated to it, and the expensive cloth that covered it. Other classical Rabbis portray Achan as guilty of more earthly crimes, claiming that he had committed incest, or performed work on the sabbath (equally immoral in their eyes).

In the narrative, before Achan is stoned to death, he first confesses his actions, which the Classical Rabbis argued would have saved him from Gehenna (the classical-era Jewish conception of hell). From a textual point of view, it exonerates the Israelites from any question of condemning a man without evidence other than cleromancy, and thus avoids questions over the validity of supernatural tests of guilt.

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c

Ginzberg, Louis (1901). "Achan". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. 1. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

Ginzberg, Louis (1901). "Achan". In Singer, Isidore; et al. (eds.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. 1. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

- ^ Niels Peter Lemche (2010). The A to Z of Ancient Israel. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8108-7565-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Achan". Encyclopaedia Judaica.

References[]

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Achan". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Achan". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons. Missing or empty

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons. Missing or empty |title=(help)

- Hebrew Bible people

- People executed by stoning

- Book of Joshua