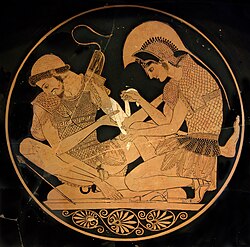

Achilles and Patroclus

The relationship between Achilles and Patroclus is a key element of the stories associated with the Trojan War. Its exact nature has been a subject of dispute in both the Classical period and modern times. In the Iliad, Homer describes a deep and meaningful relationship between Achilles and Patroclus, where Achilles is tender toward Patroclus but callous and arrogant toward others. Homer never explicitly casts the two as lovers,[1][2] but they were depicted as lovers in the archaic and classical periods of Greek literature, particularly in the works of Aeschylus, Aeschines and Plato.[3][4]

In the Iliad[]

Achilles and Patroclus are close comrades in the war against the Trojans. Due to his anger at being dishonored by Agamemnon, Achilles chooses not to participate in the battle. As the tide of the war turns against the Achaeans, Patroclus convinces Achilles to let him lead the Myrmidon army into battle wearing Achilles’ armor. Patroclus succeeds in beating back the Trojan forces, but is killed in battle by Hector.

News of Patroclus’ death reaches Achilles through Antilochus, which throws him into deep grief. The earlier steadfast and unbreakable Achilles agonizes, touching Patroclus’ dead body, smearing himself with ash and fasting. He laments Patroclus’ death using language very similar to that later used by Andromache of Hector. He also requests that when he dies, his ashes be mixed with Patroclus'.

The rage that follows from Patroclus’ death becomes the prime motivation for Achilles to return to the battlefield. He returns to battle with the sole aim of avenging Patroclus’ death by killing Hector, despite a warning that doing so would cost him his life. After defeating Hector, Achilles drags his corpse by the heels behind his chariot.

Achilles' strongest interpersonal bond is with Patroclus. As Gregory Nagy points out:

For Achilles ... in his own ascending scale of affection as dramatized by the entire composition of the Iliad, the highest place must belong to Patroklos.... In fact Patroklos is for Achilles the πολὺ φίλτατος ... ἑταῖρος — the ‘hetaîros who is the most phílos by far’ (XVII 411, 655).[5]

Hetaîros meant companion or comrade; in Homer it is usually used of soldiers under the same commander. While its feminine form (hetaîra) would be used for courtesans, a hetaîros was still a form of soldier in Hellenistic and Byzantine times. In ancient texts, philos (often translated "brotherly love") denoted a general type of love, used for love between family, between friends, a desire or enjoyment of an activity, as well as between lovers.

Achilles is the most dominant, and among the warriors in the Trojan War he has the most fame. Patroclus performs duties such as cooking, feeding, and grooming the horses, yet is older than Achilles. Both characters also sleep with women:

But Achilles slept in the innermost part of the well-builded hut, and by his side lay a woman that he had brought from Lesbos, [665] even the daughter of Phorbas, fair-cheeked Diomede. And Patroclus laid him down on the opposite side, and by him in like manner lay fair-girdled Iphis, whom goodly Achilles had given him when he took steep Scyrus, the city of Enyeus. (Iliad, IX.663–669)

Achilles' attachment to Patroclus is an archetypal male bond that occurs elsewhere in Greek culture: the mythical Damon and Pythias, the legendary Orestes and Pylades, and the historical Harmodius and Aristogeiton are pairs of comrades who gladly face danger and death for and beside each other.[6]

In the Oxford Classical Dictionary, David M. Halperin writes:

Homer, to be sure, does not portray Achilles and Patroclus as lovers (although some Classical Athenians thought he implied as much (Aeschylus fragments 135, 136 Radt; Plato Symposium 179e–180b; Aeschines Against Timarchus 133, 141–50) ), but he also did little to rule out such an interpretation.[7]

Classical views in antiquity[]

In the 5th and 4th centuries BC, the relationship was portrayed as same-sex love in the works of Aeschylus, Plato, Pindar and Aeschines.

In Athens, the relationship was often viewed as being loving and pederastic.[8] The Greek custom of paiderasteia between members of the same-sex, typically men, was a political, intellectual, and sometimes sexual relationship.[9] Its ideal structure consisted of an older erastes (lover, protector), and a younger eromenos (the beloved). The age difference between partners and their respective roles (either active or passive) was considered to be a key feature.[10] Writers that assumed a pederastic relationship between Achilles and Patroclus, such as Plato and Aeschylus, were then faced with a problem of deciding who must be older and play the role of the erastes.[11]

Aeschylus, in his lost tragedy The Myrmidons (5th century BC), assigned Achilles the role of erastes or protector (since he had avenged his lover's death, even though the gods told him it would cost him his own life), and assigned Patroclus the roles of eromenos. Achilles publicly laments Patroclus’ death, addressing the corpse and criticizing him for letting himself be killed. In a surviving fragment of the play, Achilles speaks of “the reverent company” of Patroclus’ thighs and how Patroclus was “ungrateful for many kisses.”[12][13]

Pindar's comparison of the adolescent boxer Hagesidamus and his trainer Ilas to Patroclus and Achilles in Olympian 10.16-21 (476 BC) as well as the comparison of Hagesidamus to Zeus' lover Ganymede in Olympian 10.99-105 suggest that student and trainer had a romantic relationship, especially after Aeschylus' depiction of Achilles and Patroclus as lovers in his play Myrmidons.[14]

In Plato's Symposium, written c. 385 BC, the speaker Phaedrus holds up Achilles and Patroclus as an example of divinely approved lovers. Phaedrus argues that Aeschylus erred in claiming Achilles was the erastes because Achilles was more beautiful and youthful than Patroclus (characteristics of the eromenos) as well as more noble and skilled in battle (characteristics of the erastes).[15][16] Instead, Phaedrus suggests that Achilles is the eromenos whose reverence of his erastes, Patroclus, was so great that he would be willing to die to avenge him.[16]

Plato's contemporary, Xenophon, in his own Symposium, had Socrates argue that Achilles and Patroclus were merely chaste and devoted comrades.[8] Xenophon cites other examples of legendary comrades, such as Orestes and Pylades, who were renowned for their joint achievements rather than any erotic relationship.[16] Notably, in Xenophon's Symposium, the host Kallias and the young pankration victor Autolycos are called erastes and eromenos.

Further evidence of this debate is found in a speech by an Athenian politician, Aeschines, at his trial in 345 BC. Aeschines, in placing an emphasis on the importance of paiderasteia to the Greeks, argues that though Homer does not state it explicitly, educated people should be able to read between the lines: "Although (Homer) speaks in many places of Patroclus and Achilles, he hides their love and avoids giving a name to their friendship, thinking that the exceeding greatness of their affection is manifest to such of his hearers as are educated men."[10] Most ancient writers (among the most influential Aeschylus, Plutarch, Theocritus, Martial and Lucian)[4] followed the thinking laid out by Aeschines.

According to William A. Percy III, there are some scholars, such as Bernard Sergent, who believe that in Homer's Ionian culture there existed a homosexuality that had not taken on the form it later would in pederasty.[17] However, Sergent and others have argued that it had, though it was not reflected in Homer. Sergent asserts that ritualized man-boy relations were widely diffused through Europe from prehistoric times.[citation needed]

Attempts to edit Homer's text were undertaken by Aristarchus of Samothrace in Alexandria around 200 BC. Aristarchus believed that Homer did not intend the two to be lovers. However, he did agree that the "we-two alone" passage did imply a love relation and argued it was a later interpolation.[18]

When Alexander the Great and his confidant Hephaestion passed through the city of Troy on their Asian campaign, Alexander honoured the sacred tomb of Achilles and Patroclus in front of the entire army, and this was taken as a clear declaration of their own friendship. The joint tomb and Alexander's action demonstrates the perceived significance of the Achilles-Patroclus relationship at that time (around 334 BC).[19][20]

Post-classical and modern interpretations[]

Commentators from the Classical period on have interpreted the relationship through the lens of their own cultures. As a rule, the post-classical tradition shows Achilles as heterosexual and having an exemplary platonic friendship with Patroclus. Medieval Christian writers deliberately suppressed the homoerotic nuances of the figure.[21]

David Halperin compares Achilles and Patroclus to the traditions of Jonathan and David, and Gilgamesh and Enkidu, which are approximately contemporary with the Iliad's composition. He argues that while a modern reader is inclined to interpret the portrayal of these intense same-sex male warrior friendships as being fundamentally homoerotic, it is important to consider the greater themes of these relationships:

The thematic insistence on mutuality and the merging of individual identities, although it may invoke in the minds of modern readers the formulas of heterosexual romantic love […] in fact situates avowals of reciprocal love between male friends in an honorable, even glamorous tradition of heroic comradeship: precisely by banishing any hint of subordination on the part of one friend to the other, and thus any suggestion of hierarchy, the emphasis on the fusion of two souls into one actually distances such a love from erotic passion.[22]

According to Halperin, these extra-institutional relationships were of necessity portrayed by using the language of other, institutionalized love relationships, such as those of parent/child and husband/wife. This can explain the overtones in Book 19 of the Iliad wherein Achilles mourns Patroclus (lines 315–337) in a similar manner used previously by Briseis (lines 287–300).[8]

Shakespeare[]

William Shakespeare's play Troilus and Cressida portrays Achilles and Patroclus as lovers in the eyes of the Greeks.[23] Achilles' decision to spend his days in his tent with Patroclus is seen by Ulysses and many other Greeks as the chief reason for anxiety about Troy.[24]

See also[]

- Homosexuality in ancient Greece

- Homosexuality in the militaries of ancient Greece

- Nisus and Euryalus

Notes[]

- ^ Fox, Robin (2011). The Tribal Imagination: Civilization and the Savage Mind. Harvard University Press. p. 223. ISBN 9780674060944.

There is certainly no evidence in the text of the Iliad that Achilles and Patroclus were lovers.

- ^ Martin, Thomas R (2012). Alexander the Great : the story of an ancient life. Cambridge University Press. pp. 99–100. ISBN 978-0521148443.

The ancient sources do not report, however, what modern scholars have asserted: that Alexander and his very close friend Hephaestion were lovers. Achilles and his equally close friend Patroclus provided the legendary model for this friendship, but Homer in the Iliad never suggested that they had sex with each other. (That came from later authors.)

- ^ Achilles in Love: Intertextual Studies

- ^ "Aeschines, Against Timarchus, section 133".

- ^ Gregory Nagy, The Best of the Achaeans, second edition. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999. p. 105 (online edition). ISBN 0-8018-6015-6.

- ^ Warren Johansson, Encyclopedia of Homosexuality, USA, 1990

- ^ Oxford Classical Dictionary, third edition. Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, eds. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996. p. 721. ISBN 0-19-866172-X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c W. M. Clarke, "Achilles and Patroclus in Love," in Hermes 106. Bd., H. 3, pp. 381-396, Franz Steiner Verlag, 1978 JOSTOR

- ^ Nicole, Holmen (2010-01-01). "Examining Greek Pederastic Relationships". Inquiries Journal. 2 (2).

- ^ Marguerite, Johnson; Ryan, Terry (2005). Sexuality in Greek and Roman Society and Literature: A Sourcebook. New York: Routledge. pp. 3. ISBN 9780415173315 – via Google Books.

- ^ Percy, William A. (1998). Pederasty and Pedagogy in Archaic Greece. Chicago: University of Illinois Press. pp. 39. ISBN 9780252067402 – via Google Books.

- ^ Michelakis, Pantelis (2007). Achilles in Greek Tragedy. Cambridge University Press. p. 51. ISBN 978-0-521-81843-8.

- ^ Aesch. Myrmidons fr. 135 Radt.

- ^ Hubbard, T (2005). "Pindar's Tenth Olympian and athlete-trainer pederasty". J Homosex. 49 (3–4): 137–71. doi:10.1300/j082v49n03_05. PMID 16338892.

- ^ William Armstrong Percy III, "Reconsiderations about Greek Homosexualities," in Same–Sex Desire and Love in Greco-Roman Antiquity and in the Classical Tradition of the West, Binghamton, 2005; p. 19

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Dover, Kenneth J. (1978). Greek Homosexuality. New York: Vintage Books. pp. 197–199. ISBN 978-0-394-74224-3.

- ^ Percy, William Armstrong (2005). "Reconsiderations About Greek Homosexualities". Journal of Homosexuality. 49 (3–4): 13–61. doi:10.1300/j082v49n03_02. PMID 16338889.

- ^ "Homosexuality & Civilization" by Louis Crompton. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1993, p. 6.

- ^ Age of Alexander, Life of Alexander by Plutarch, p. 294, Penguin Classics edition 1973

- ^ Arrian. The Campaigns of Alexander. p. 67, Penguin Classics edition (1958).

- ^ Katherine Callen King, Achilles: Paradigms of the War Hero from Homer to the Middle Ages, Berkeley, 1987

- ^ Halperin, David M. (2000). "How to do the history of male homosexuality" (PDF). GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 6: 87–124. doi:10.1215/10642684-6-1-87. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-09.

- ^ Shakespeare, William (1609-01-01), "Troilus and Cressida", The Oxford Shakespeare: Troilus and Cressida, Oxford University Press, pp. 47–48, doi:10.1093/oseo/instance.00027413, ISBN 9780198129035

- ^ Shakespeare, William (1609-01-01), "Troilus and Cressida", The Oxford Shakespeare: Troilus and Cressida, Oxford University Press, pp. 24–5, doi:10.1093/oseo/instance.00027413, ISBN 9780198129035

- Achaean Leaders

- Achilles

- Fictional LGBT couples

- LGBT themes in Greek mythology

- Same-sex couples