Adam Link

The topic of this article may not meet Wikipedia's general notability guideline. (November 2021) |

| Adam Link | |

|---|---|

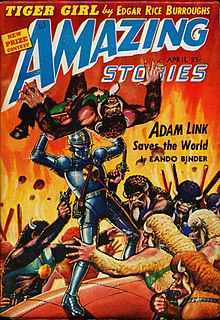

Adam Link in cover of Amazing Stories, April 1942, art by Robert Fuqua | |

| First appearance | I, Robot |

| Last appearance | Adam Link Saves the World |

| Created by | Eando Binder |

| Portrayed by | Read Morgan John Novak |

| In-universe information | |

| Species | Robot |

| Gender | Male |

Adam Link is a fictional robot, made in the likeness of a man, who becomes self-aware, and the protagonist of several science fiction short stories written by Eando Binder, the pen name of Earl Andrew Binder and his brother, Otto Binder. The stories were originally published in the science fiction magazine Amazing Stories from 1939 to 1942. In all, ten Adam Link stories were published. In The American Robot: A Cultural History, Dustin A. Abnet says that Adam was the "most popular science fiction robot of the era".[1]

The first story, published in January 1939, was "I, Robot" (not to be confused with the book of the same name by Isaac Asimov). The story is written in the first person, from the point of view of a newly sentient robot, in the form of a written confession. In the story, the robot explains that it was built and educated by Dr. Charles Link. When Dr. Link dies in an accident, the housekeeper assumes that the robot murdered his master, and the robot goes on the run. At the end of the story, the robot realizes that its flight endangers other living creatures, and prepares to turn itself off.

Immediately popular, the robot was featured in nine more stories published in Amazing Stories.[2] The character was translated into the comic book medium in the pages of EC Comics' Weird Science-Fantasy in 1955, and then in Warren Publishing's Creepy in the mid-60s. In 1964, the original story was also adapted for television in The Outer Limits.

Paperback Library published a mass market paperback collection entitled Adam Link - Robot in 1965, which tells the character's story in a first person narrative from Creation to Citizenship in twenty-one chapters. The collection ends with an Epilogue, encouraging humanity's future. The volume was reprinted in 1970 by Fawcett Crest Books and by Warner in 1974; Ballantine Books also reprinted the book.

Stories[]

All stories were published in Amazing Stories.[3]

- "I, Robot", Jan 1939 (story)

- "The Trial of Adam Link, Robot", July 1939 (story)

- "Adam Link in Business", Jan 1940 (story)

- "Adam Link’s Vengeance", Feb 1940 (story)

- "Adam Link, Robot Detective", May 1940 (story)

- "Adam Link, Champion Athlete", July 1940 (story)

- "Adam Link Fights a War", Dec 1940 (story)

- "Adam Link in the Past", Feb 1941 (story)

- "Adam Link Faces a Revolt", May 1941 (story)

- "Adam Link Saves the World", Apr 1942 (story)

Influence[]

Isaac Asimov says that his robot stories were influenced by the first Adam Link story: "It certainly caught my attention. Two months after I read it, I began 'Robbie', about a sympathetic robot, and that was the start of my positronic robot series. Eleven years later, when nine of my robot stories were collected into a book, the publisher named the collection I, Robot over my objections. My book is now the more famous, but Otto's story was there first."[4]

Adaptations[]

"I, Robot" and "The Trial of Adam Link, Robot" were adapted for a 1964 episode of the television show The Outer Limits called "I, Robot".[5] In the 1995 revival of The Outer Limits, the show again aired an adaptation titled "I, Robot". Both versions featured Leonard Nimoy.

The series has been adapted for comic books twice, once for EC Comics' Weird Science-Fantasy in 1955 (issues 27-29), and again for Warren Publishing's Creepy in 1965-67 (issues 2, 4, 6, 8–9, 12–13 and 15).[6] In each case, the adaptation was scripted by Binder and drawn by Joe Orlando. Both series were discontinued before they could be completed.

In 1964, an adaptation of "Adam Link's Vengeance" was published in the fanzine Fantasy Illustrated # 1, script by Otto Binder and illustrated by D. Bruce Berry and Bill Spicer, the adaptation won the Alley Award for Best Fan Comic Strip of the same year.[7][8]

References[]

- ^ Abnet, Dustin A. (2020). The American Robot: A Cultural History. University of Chicago Press. pp. 179–184. ISBN 978-0226692715. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Schelly, Bill (2016). Otto Binder: The Life and Work of a Comic Book and Science Fiction Visionary. North Atlantic Books. pp. 60–61. ISBN 9781623170370. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Wood, Edward (Fall 1952). "An Amazing Quarter Century". The Journal of Science Fiction. 1 (2): 16. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac (1979). Isaac Asimov Presents the Great SF Stories. DAW Books.

- ^ Schow, David J.; Frentzen, Jeffrey (1986). The Outer Limits: The Official Companion. Ace Books. p. 333. ISBN 978-0441370818.

- ^ Cooke, Jon B.; Roach, David (2001). The Warren Companion. TwoMorrows Publishing. pp. 195–196. ISBN 9781893905085.

- ^ Schelly, Bill. Founders of Comic Fandom, 2010.

- ^ Schelly, Bill (2016-06-07). Otto Binder: The Life and Work of a Comic Book and Science Fiction Visionary. North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-62317-038-7.

External links[]

- Adam Link at Tales of Future Past

- The Outer Limits (1964) "I, Robot" at IMDb

- The Outer Limits (1995) "I, Robot" at IMDbi-robot.html "I, Robot" on The Outer Limits (1964)

- Fictional robots