Adriana Lecouvreur

| Adriana Lecouvreur | |

|---|---|

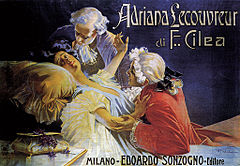

| Opera by Francesco Cilea | |

Aleardo Villa – Adriana Lecouvreur | |

| Librettist | Arturo Colautti |

| Language | Italian |

| Based on | Adrienne Lecouvreur by Eugène Scribe and Ernest Legouvé |

| Premiere | 6 November 1902 Teatro Lirico, Milan |

Adriana Lecouvreur is an opera in four acts by Francesco Cilea to an Italian libretto by Arturo Colautti, based on the 1849 play Adrienne Lecouvreur by Eugène Scribe and Ernest Legouvé. It was first performed on 6 November 1902 at the Teatro Lirico in Milan.

Background[]

The same play by Scribe and Legouvé which served as a basis for Cilea's librettist was also used by at least three different librettists for operas carrying exactly the same name, Adriana Lecouvreur, and created by three different composers. The first was an opera in three acts by Tommaso Benvenuti (premiered in Milan in 1857). The next two were lyric dramas in 4 acts by Edoardo Vera (to a libretto by Achille de Lauzières) which premiered in Lisbon in 1858, and by Ettore Perosio[1] (to a libretto by his father),[2] premiered in Geneva in 1889. After Cilea created his own Adriana, however, none of those by others were performed anymore and they remain largely unknown today.[3]

The opera is based on the life of the French actress Adrienne Lecouvreur (1692–1730). While there are some actual historical figures in the opera, the episode it recounts is largely fictional; its death-by-poisoned-violets plot device is often signalled as verismo opera's least realistic.[4] It is often condemned as being among the most confusing texts ever written for the stage, and cuts that have often been made in performance only make the story harder to follow.[citation needed] The running time of a typical modern performance is about 135 minutes (excluding intervals).

Performance history[]

The opera premiered at the Teatro Lirico, Milan, on 6 November 1902, with the well-known verismo soprano in the title role, Enrico Caruso in the role of Maurizio, and the lyric baritone Giuseppe De Luca as Michonnet.

The opera was first performed in the United States by the San Carlo Opera Company on January 5, 1907, at the French Opera House in New Orleans with Tarquinia Tarquini in the title role. It gained its Metropolitan Opera premiere on 18 November 1907 (in a performance starring Lina Cavalieri and Caruso).[5] It had a run of only three performances that season, however, due in large part to Caruso's ill-health. The opera was not performed again at the Met until a new production was mounted in 1963, with Renata Tebaldi in the title role.[6] That 1963 production continued to be remounted at the same theatre, with differing casts, for the next few decades. It was in the lead role of this opera that the Spanish tenor Plácido Domingo made his Met debut in 1968,[7] alongside Renata Tebaldi. He sang again in Adriana Lecouvreur in February 2009.[8]

The title role in Adriana Lecouvreur has always been a favorite of sopranos with large voices, which tend to sit less at the very top of their range. This part has a relatively low tessitura, going no higher than Bb,[citation needed] and only a few times at that, but requires great vocal power, and is a meaty and challenging one to tackle on a dramatic level – especially during the work's so-called "Recitation" and death scene. Famous Adrianas of the past 75 years have included Claudia Muzio, Magda Olivero,[9] Renata Tebaldi, Carla Gavazzi, Leyla Gencer, Montserrat Caballé, Raina Kabaivanska, Renata Scotto, Mirella Freni, and Joan Sutherland. Angela Gheorghiu tackled the role at the Royal Opera, London, in 2010 with Jonas Kaufmann as Maurizio.[10] It was the first new production (directed by David McVicar) at the Royal Opera House since 1906. [11] Angela Gheorghiu has reprised the role with great critical acclaim, in the same production, at the Vienna State Opera, when the opera was presented for the very first time on its stage (2014),[12] Paris (2015) [13] and again in London, when she celebrated 25 years on the stage of the Royal Opera House and 150 performances with the company (2017) [14] The Met presented a production new to that house by David McVicar on 31 December 2018, with Anna Netrebko in the title role, Piotr Beczała as Maurizio and Anita Rachvelishvili as the Princess de Bouillon.[15]

A recording of part of the opera's last act duet "No, più nobile", rearranged into a self-contained tenor aria, was made by Caruso as early as 1902 for the Gramophone & Typewriter Company in Milan and its affiliates, with Cilea at the piano.

Roles[]

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, November 6, 1902 Conductor: Cleofonte Campanini |

|---|---|---|

| Adriana Lecouvreur (Adrienne Lecouvreur), a famous actress | soprano | |

| Maurizio (Maurice de Saxe), Count of Saxony | tenor | Enrico Caruso |

| Princess de Bouillon | mezzo-soprano | Edvige Ghibaudo |

| Prince de Bouillon | bass | Edoardo Sottolana |

| The Abbé de Chazeuil | tenor | Enrico Giordani |

| Michonnet, a stage manager | baritone | Giuseppe De Luca |

| Mlle Jouvenot | soprano | |

| Mlle Dangeville | mezzo-soprano | |

| Poisson | tenor | |

| Quinault | bass | |

| Major-domo | tenor |

Synopsis[]

- Place: Paris, France

- Time: 1730[16]

Act 1[]

Backstage at the Comédie-Française

The company is preparing for a performance and bustling around Michonnet, the stage manager. The Prince de Bouillon, admirer and patron of the actress Duclos, is also seen backstage with his companion, the Abbé. Adriana enters, reciting, and replies to the others' praise with 'Io son l'umile ancella' ("I am the humble servant of the creative spirit"). Left alone with Adriana, Michonnet wants to express his love for her. However, Adriana explains that she already has a lover: Maurizio, a soldier of the Count of Saxony. Maurizio enters and declares his love for Adriana, 'La dolcissima effigie.' They agree to meet that night, and Adriana gives him some violets to put in his buttonhole. The Prince and the Abbé return. They have intercepted a letter from Duclos, in which she requests a meeting with Maurizio later that evening at the Prince's villa. The Prince, hoping to expose the tryst, decides to invite the entire troupe there after the performance. On receiving Duclos's letter, Maurizio cancels his appointment with Adriana, who in turn opts to join the Prince's party.

Act 2[]

A villa by the Seine

The Princess de Bouillon, not the actress Duclos (who was only acting as her proxy), is anxiously waiting for Maurizio ("Acerba voluttà, dolce tortura"). When Maurizio enters, she sees the violets and asks how he came by them. Maurizio presents them to her, but confesses that he no longer loves her. She deduces that he loves someone else, but soon she's forced to hide when the Prince and the Abbé suddenly arrive. Maurizio realizes that they think he is with Duclos. Adriana enters and learns that Maurizio isn't a soldier at all, but the disguised Count of Saxony himself. He tells Adriana the assignation was political, and that they must arrange the escape of a woman who is in hiding nearby. Adriana trusts him and agrees to help. During the intermezzo that follows, the house is darkened, and Adriana tells the Princess that this is her opportunity to escape. However, the two women are mutually suspicious, and the rescue attempt turns into a blazing quarrel before the Princess finally leaves. Michonnet, the stage manager, discovers a bracelet dropped by the Princess, which he gives to Adriana.

Act 3[]

The Hôtel de Bouillon

The Princess is desperate to discover the identity of her rival. The Prince, who has an interest in chemistry, is storing a powerful poison that the government has asked him to analyze. The couple host a reception, at which guests note the arrival of Michonnet and Adriana. The Princess thinks she recognizes the latter's voice, and announces that Maurizio has been wounded in a duel. Adriana faints. Soon afterwards, however, when Maurizio enters uninjured, Adriana is ecstatic. He sings of his war exploits ("Il russo Mencikoff"). A ballet is performed: the 'Judgement of Paris.' Adriana learns that the bracelet Michonnet found belongs to the Princess. Realizing that they are rivals for Maurizio's affection, the Princess and Adriana challenge each other. When the former pointedly suggests that Adriana should recite a scene from 'Ariadne Abandoned', the Prince asks instead for a scene from Phèdre. Adriana uses the final lines of the text to make a headstrong attack on the Princess, who swears to have her revenge.

Act 4[]

A room in Adriana's house

It's Adriana's name day, and Michonnet is waiting in her home for her to awaken. Adriana is consumed with anger and jealousy. Her colleagues come to visit, bringing her gifts and trying to persuade her to return to the stage. One of these gifts is a diamond necklace, recovered by Michonnet, which Adriana had pawned to help pay off Maurizio's debts. A small casket arrives. It contains a note from Maurizio, along with the violets Adriana had given him at the theater. Adriana, hurt, kisses the flowers ("Poveri fiori") and throws them into the fire. Maurizio enters, hoping to marry her. They embrace, and he notices that she's shaking. She quickly becomes deranged, and Michonnet and Maurizio - who'd presented the violets to the Princess - realize that Adriana has been poisoned. For a moment, she becomes lucid again ("Ecco la luce"), then dies.

Recordings[]

| Year | Cast (Adriana Lecouvreur, La Principessa di Bouillon, Maurizio, Michonnet) |

Conductor, Opera house and orchestra |

Label[17] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1950 | Mafalda Favero, Elena Nicolai, Nicola Filacuridi, |

Federico Del Cupolo, La Scala Orchestra and Chorus, Milan |

CD: VAI Cat: 1230 |

| 1951 | Carla Gavazzi, , Giacinto Prandelli, Saturno Meletti |

, RAI Orchestra and Chorus, Milan |

CD: Cetra Opera Collection – Warner Fonit Cat: 8573 87480-2 |

| 1959 | Magda Olivero, Giulietta Simionato, Franco Corelli, Ettore Bastianini |

Mario Rossi, San Carlo Opera Orchestra and Chorus, Naples (live recording) |

CD: Opera D'Oro Cat: 7037 |

| 1961 | Renata Tebaldi, Giulietta Simionato, Mario Del Monaco, Giulio Fioravanti |

Franco Capuana, Santa Cecilia Academy Orchestra and Chorus, Rome |

CD: Decca Cat: 430256-2 |

| 1975 | Montserrat Caballé, Plácido Domingo, Janet Coster, |

Gianfranco Masini, Orchestra and Chorus (live recording) |

CD: Opera D'Oro Cat: OPD-1194 |

| 1977 | Renata Scotto, Elena Obraztsova, Giacomo Aragall, Giuseppe Taddei |

Gianandrea Gavazzeni, San Francisco Opera Orchestra and Chorus (Recording of a performance in the War Memorial Opera House, San Francisco, September) |

CD: Myto Records Cat: 2MCD 005 234 |

| 1977 | Renata Scotto, Elena Obraztsova, Plácido Domingo, Sherrill Milnes |

James Levine, Philharmonia Orchestra, Ambrosian Opera Chorus |

CD: CBS Records Cat: M2K 79310 |

| 1988 | Joan Sutherland, , Carlo Bergonzi, Leo Nucci |

Richard Bonynge, Welsh National Opera Orchestra and Chorus, Cardiff, Wales |

CD: Decca Cat: 475 7906 |

| 1989 | Mirella Freni, Fiorenza Cossotto, Peter Dvorský, Ivo Vinco |

Gianandrea Gavazzeni, La Scala Orchestra and Chorus, Milan |

DVD: Opus Arte Cat: OALS 3011D |

| 2000 | Daniela Dessì, Olga Borodina, Sergei Larin, |

, La Scala Orchestra and Chorus, Milan (Audio and video recordings of a performance (or of performances) at La Scala, January) |

DVD: TDK "Mediactive" Cat: DV-OPADL Audio CD: The Opera Lovers Cat: ADR 200001 |

| 2010 | Angela Gheorghiu, Olga Borodina, Jonas Kaufmann, Alessandro Corbelli |

Mark Elder, The Royal Opera House Orchestra and Chorus, London (Video recording of a performance at the Royal Opera House, November) |

DVD and Blu-ray: Decca [18] |

| 2019 | Anna Netrebko, Anita Rachvelishvili, Piotr Beczała, Ambrogio Maestri |

Gianandrea Noseda, Metropolitan Opera Orchestra and Chorus (Video recording of a performance at The Met on 12 January) |

Met Opera on Demand (subscription required)[19] |

References[]

Notes

- ^ Ettore Perosio, details, familiaperosio.com.ar

- ^ Patrick O'Connor (2002). "Perosio, Ettore". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.O903864. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0. Retrieved April 19, 2020.

- ^ Casaglia, Gherardo (2005). "History of performances of Adriana Lecouvreur". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- ^ However, for the reference on how widespread in the 18th century problem of poisoning was one could read the chapter on the "Slow Poisoners" within Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds by Charles Mackay (pp. 565–592).

- ^ "Met performance of 18 November 1907". archives.metoperafamily.org. Retrieved Nov 20, 2020.

- ^ "Met performance of 21 January 1963". archives.metoperafamily.org. Retrieved Nov 20, 2020.

- ^ "Met performance of 28 September 1968". archives.metoperafamily.org. Retrieved Nov 20, 2020.

- ^ "Met performance of 6 February 2009". archives.metoperafamily.org. Retrieved Nov 20, 2020.

- ^ Olivero returned to the stage in 1951, after a ten-year retirement, at Cilea's insistent request that she agree to perform the role of Adriana (Rosenthal, H. and Warrack, J., "Olivero, Magda", The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Opera, 2nd edition, Oxford University Press, 1979, pp. 358–359; ISBN 0-19-311318-X).

- ^ Christiansen, Rupert (19 November 2010). "Adriana Lecouvreur, Royal Opera House, London, review". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ "Old2New". Retrieved Nov 20, 2020.

- ^ "112 years in the making: Adriana Lecouvreur's belated première in Vienna". bachtrack.com. Retrieved Nov 20, 2020.

- ^ "Adriana Lecouvreur - Opéra national de Paris (2015) (Production - Paris, france) | Opera Online - The opera lovers web site". www.opera-online.com. Retrieved Nov 20, 2020.

- ^ "The iconic Angela Gheorghiu celebrates 25 years with the Royal Opera House". Evening Standard. Feb 16, 2017. Retrieved Nov 20, 2020.

- ^ Tommasini, Anthony (1 January 2019). "Review: Met Opera's Adriana Lecouvreur Bristles With Passion and Danger". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- ^ The synopsis by Simon Holledge was first published at Operajaponica.org and appears here by permission.

- ^ Recordings of the opera on operadis-opera-discography.org.uk Retrieved 30 July 2012

- ^ "Cilea: Adriana Lecouvreur". Presto Classical. Retrieved Nov 20, 2020.

- ^ Adriana Lecouvreur, 12 January 2019, Met Opera on Demand.(subscription required)

Further reading[]

- English Libretto of Adriana Lecouvreur

- Kobbé, Gustav (1976). The Complete Opera Book. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 1205–1209.

External links[]

Media related to Adriana Lecouvreur (opera) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Adriana Lecouvreur (opera) at Wikimedia Commons- Adriana Lecouvreur: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Work details, libretto, (in German and Italian)

- Portrait of the opera in the online opera guide www.opera-inside.com

- Italian-language operas

- Operas by Francesco Cilea

- 1902 operas

- Operas

- Operas set in France

- Verismo operas

- Operas set in the 18th century

- Operas based on real people

- Operas based on plays

- Operas based on works by Eugène Scribe

- Cultural depictions of Adrienne Lecouvreur