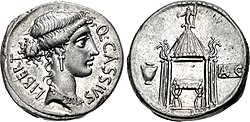

Trial of the Vestal Virgins (114–113 BC)

Aemilia, Licinia and Marcia were Roman vestal Virgins, who were prosecuted for having broken the vow of chastity in two famous trials between 115 and 113 BC.[2] The first trial was conducted by the Pontifex Maximus Metellus Delmaticus, who sentenced to death Aemilia in 114 BC. The decision to spare the other two vestals nevertheless triggered outrage and a special court headed by Cassius Longinus Ravilla was created the following year to restart the investigations. Licinia and Marcia were subsequently put to death as well. The trials were heavily influenced by the political background and network of the participants.

The individuals[]

Aemilia was a member of the patrician gens Aemilia. Licinia was a member of the plebeian gens Licinia and the daughter of Gaius Licinius Crassus. In 123, her dedication of an altar was cancelled by the pontiffs because it had been made without the approval of the people. Marcia was a member of the plebeian gens Marcia and possibly the daughter of Quintus Marcius Rex, praetor in 144 BC.

The trials[]

In 115 BC, the vestals Aemilia, Marcia and Licinia were put on trial accused of having broken their vow of chastity. Reportedly, Aemilia had initially been seduced by Lucius Veturius. After this, she arranged for Marcia and Licinia to have sexual relations with the male friends of her lover. Aemilia and Licinia had multiple lovers, while Marcia had a monogamous relationship with her lover. The three vestals were prosecuted after having been reported to the authorities by their slave Manius, who had assisted them in their affairs after they had promised him manumission in exchange, but never fulfilled their promise to him. According to Manius, the affairs of the vestals was widely tolerated within the Roman aristocracy. The trial was a great scandal in contemporary Rome. After a sensational trial, Aemilia was judged guilty as charged and sentenced to death by the Pontifex Maximus Lucius Caecilius Metellus Dalmaticus. Licinia and Marcia were both acquitted from charges.

The acquittal of Marcia and Licinia created public outrage in Rome because of Manius' testimony that the sexual crimes of the vestals had been an open secret and tolerated among the aristocracy, and the public interpreted the outcome as a case of corruption among the elite. The case against Licinia and Marcia was therefore reopened the following year by the tribune , who took the unusual step to transfer the case from the pontiff to Lucius Cassius Longinus Ravilla, who was known for his severity. They (or at least Licinia) were defended by the orator Lucius Licinius Crassus.[4]

The second trial ended in a guilty verdict for both Licinia and Marcia who were both judged guilty as charged to be executed by live burial. During the trial, several men were implicated as the alleged lovers of the vestals and prosecuted. This involved several prominent people and the process has by some been interpreted as political. Among those men implicated were the orator Marcus Antonius, who was however acquitted. Four men were judged guilty as charged for having been the lovers of the vestals, and sentenced to be buried alive at the forum boarium.

After the trial, several rituals were conducted to clean the holy fire of Vesta from the pollution which was believed to have soiled it because of the crimes.

References[]

- ^ Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage, p. 440.

- ^ Friedrich Münzer: Marcius 114). In: Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft (RE). Band XIV,2, Stuttgart 1930, Sp. 1601 f.

- ^ Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage, p. 452.

- ^ A Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology

Bibliography[]

- T. Robert S. Broughton, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic, American Philological Association, 1952–1986.

- Michael Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage, Cambridge University Press, 1974.

- 114 BC deaths

- Vestal Virgins

- 1st-century BC Roman women

- Executed Roman women