After the Fox

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2013) |

| After the Fox | |

|---|---|

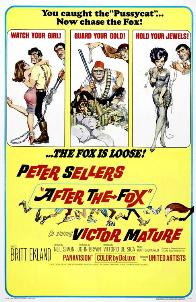

Theatrical release poster by Frank Frazetta | |

| Directed by | Vittorio De Sica |

| Screenplay by | Neil Simon (screenplay) Cesare Zavattini |

| Produced by | John Bryan |

| Starring | Peter Sellers Britt Ekland Lydia Brazzi Paolo Stoppa Victor Mature Tino Buazzelli Vittorio De Sica |

| Cinematography | Leonida Barboni |

| Edited by | Russell Lloyd |

| Music by | Burt Bacharach Piero Piccioni |

Production company | Delgate / Nancy Enterprises |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date | 1966 |

Running time | 103 min |

| Countries | Italy United Kingdom |

| Languages | English Italian |

| Box office | $2,296,970 (rentals)[1] |

After the Fox (Italian: Caccia alla volpe) is a 1966 heist comedy film directed by Vittorio De Sica and starring Peter Sellers, Victor Mature and Britt Ekland. The English-language screenplay is by Neil Simon and De Sica's longtime collaborator Cesare Zavattini.

Despite its notable credits, the film was poorly received when it was released. It has gained a cult following for its numerous in-jokes skewering pompous directors (including Cecil B. DeMille, Federico Fellini, Michelangelo Antonioni and De Sica); movie stars; their starstruck audiences; and pretentious film critics.[2] The film was remade in 2010 in Hindi as Tees Maar Khan.[3]

Plot[]

Outside of Cairo, Okra (Akim Tamiroff), using a bikini-clad accomplice (Maria Grazia Buccella) as a distraction, hijacks $3 million in gold bullion. The thieves need a way to smuggle the two tons of gold bars into Europe. There are only four master criminals considered capable of smuggling the gold, but each is ruled out: a Frenchman is so crippled he can barely move his wheelchair; an Irishman is so nearsighted he is arrested trying to hold up a police station instead of a bank; a German is so fat he can barely get through a door to escape; and an Italian, Aldo Vanucci (Peter Sellers), a master of disguise known as The Fox, is in prison.

Vanucci knows about the smuggling contract but is reluctant to accept it because he does not want to disgrace his mother and young sister, Gina (Britt Ekland). When his three sidekicks inform him that Gina has grown up and does not always come home after school, an enraged, over-protective Vanucci vows to escape. He impersonates the prison doctor and convinces the guards that Vanucci has tied him up in his cell and escaped. The guards capture the doctor and bring him face to face with Vanucci, who flees with the aid of his gang. Vanucci returns home where his mother tells him that Gina is working on the Via Veneto. He takes this to mean that Gina is a prostitute. Disguised as a priest, Aldo watches Gina, provocatively dressed, flirt with and kiss a fat, middle-aged man. Aldo attacks the man, but Gina, who aspires to be a movie star, is merely acting in a low-budget film. Aldo's actions cost her the job. Aldo realizes that the smuggling operation will improve his family's life. He makes contact with Okra and agrees to smuggle the gold into Italy for half of the take. Two policemen are constantly on Vanucci's trail and he uses disguises and tricks to throw them off.

After seeing a crowd mob the over-the-hill American matinee idol Tony Powell (Victor Mature), it strikes Vanucci that movie stars and film crews are idolized and have free rein in society. This insight forms the basis of his plan. Posing as an Italian neo-realist director named Federico Fabrizi, he intends to bring the gold ashore in broad daylight as part of a scene in an avant-garde film. To give the picture an air of legitimacy, he cons Powell to star in the film, which is blatantly titled The Gold of Cairo (a play on The Gold of Naples, a film De Sica directed in 1954). Powell's agent, Harry (Martin Balsam), is suspicious of Fabrizi, but his vain client wants to do the film. Fabrizi enlists the starstruck population of Sevalio, a tiny fishing village, to unload the shipment. But when the boat carrying the gold is delayed, Fabrizi must actually shoot scenes for his faux film to keep up the ruse.

The ship finally arrives and the townspeople unload the gold, but Okra double-crosses Vanucci and, using a movie smoke machine for cover, drives off with the gold. A slapstick car chase ensues, ending with Okra, Vanucci and the police crashing into each other. Vanucci, Tony Powell, Gina, Okra, and the villagers are accused of being co-conspirators and Vanucci's "film" is shown as evidence in court. An Italian film critic leaps to his feet and proclaims the disjointed footage to be a masterpiece. Vanucci suffers a crisis of conscience and confesses his guilt in court, thereby exonerating the villagers, but vows to escape from prison once again. He escapes from prison by impersonating the prison doctor again, this time tying the doctor up in his cell and walking out of the prison in his place. But when he attempts to remove the fake beard part of his disguise, Vanucci discovers the beard is real and exclaims, "Ze wrong man has escaped!"

Cast[]

- Peter Sellers as Aldo Vanucci / Federico Fabrizi

- Victor Mature as Tony Powell

- Britt Ekland as Gina Vanucci / Gina Romantica

- Martin Balsam as Harry Granoff

- Akim Tamiroff as Okra

- Maria Grazia Buccella as Okra's sister

- Maurice Denham as The Chief of Interpol

- Paolo Stoppa as Polio

- Tino Buazzelli as Siepi

- as Carlo

- Lydia Brazzi as Mamma Vanucci

- Lando Buzzanca as The Police Chief Rizzuto

- Tiberio Murgia as 1st Detective

- Francesco De Leone as 2nd Detective

- Pier Luigi Pizzi as Prison Doctor

- Enzo Fiermonte as Raymond

- Carlo Croccolo as Salvatore

- Nino Vingelli as a judge

- Vittorio De Sica as himself

Production[]

This was Neil Simon's first screenplay; at that time, he had three hit shows running on Broadway — Little Me, Barefoot in the Park and The Odd Couple. Simon said he originally wanted to write a spoof of art house films such as Last Year at Marienbad and the Michelangelo Antonioni films but the story evolved into the idea of a film-within-a-film. Aldo Vanucci brings to mind the fast-talking cons of Phil Silvers and the brilliant dialects of Sid Caesar. This is probably no coincidence since Simon wrote for both on television.[4] In his 1996 memoir Rewrites, Simon recalled that an agent suggested Peter Sellers for the lead, while Simon preferred casting "an authentic Italian", such as Marcello Mastroianni or Vittorio Gassman. Sellers loved the script and asked Vittorio De Sica to direct.[5]

De Sica's interest in the project surprised Simon, who at first dismissed it as a way for the director to support his gambling habit. De Sica said he saw a social statement to be made, namely how the pursuit of money corrupts even the arts. Simon believed De Sica also relished the opportunity to take potshots at the Italian film industry. De Sica insisted that Simon collaborate with Cesare Zavattini. Since neither spoke the other's language, the two writers worked through interpreters. Simon wrote, "He had very clear, concise, and intelligent comments that I could readily understand and agree with". Still, Simon worried that inserting social statements into what he considered a broad farce would not do justice to either. Yet, After The Fox does touch on themes found in De Sica's earlier work, namely disillusion and dignity.[5]

Sellers told the press his main reason for doing the film was the chance to work with De Sica. After the Fox was the first film produced by Sellers' new Brookfield production company, which he formed in partnership with John Bryan, a former production designer. It was also their last production, as Sellers and Bryan had a rift over De Sica. Sellers complained the director "thinks in Italian; I think in English" and wanted De Sica replaced; Bryan resisted for financial and artistic reasons. De Sica grew impatient with his petulant star; indeed, he cared for neither Sellers' performance nor Simon's screenplay.[6]

Victor Mature, who had retired from films five years earlier, was lured back to the screen by the prospect of parodying himself as Tony Powell.[6] Mature was always a self-effacing star who had no illusions about his work. At the height of his fame, he applied for membership in the Los Angeles Country Club but was told the club did not accept actors. He replied, "I'm not an actor, and I've got 64 films to prove it!"[7] A clip from Mature's 1949 film Easy Living (in which he plays an aging football star) appears in the film. He agreed to make After The Fox after a personal call from Sellers.[8] Mature also revealed that he based Tony Powell partially on De Sica, "Plus a lot of egotism, and DeMille, too — that bit with the fellow following him around with the chair all the time." Mature told the Chicago Tribune, "I not only enjoyed doing the film, but it gave me the urge to get back into pictures. They were an exciting group of people to work with."[9]

According to Neil Simon, Sellers demanded that his wife, Britt Ekland, be cast as Gina, the Fox's sister. Ekland's looks and accent were wrong for the role, but to keep Sellers happy De Sica acquiesced. Still, Simon recalled, Ekland worked hard on the film.[5] Sellers and Ekland made one other film together, The Bobo (1967).

Akim Tamiroff appears as Okra, the mastermind of the heist in Cairo. Tamiroff had been working on and off for Orson Welles playing Sancho Panza in Don Quixote, a film Welles never finished. Martin Balsam plays Tony's dyspeptic agent, Harry. Maria Grazia Buccella appears as Okra's voluptuous accomplice. Buccella was a former Miss Italy (1959) and placed third in the Miss Europe pageant. She had been considered for the role of Domino in Thunderball.[10] Lydia Brazzi, the wife of actor Rossano Brazzi, was hand-picked by De Sica for the role of the Fox's mother, despite her protests that she was not an actress.[5] Lando Buzzanca appears as the chief of police in Sevalio. Simon recalled the Italian supporting cast learned their English lines phonetically.[5]

The film's budget was $3 million, which included the construction of a replica of Rome's most famous street, the Via Veneto, on the Cinecittà lot, and location filming in the village of Sant' Angelo on Ischia in the Bay of Naples. The Sevalio sequences were shot during the height of the tourist season. Reportedly the villagers of Sant' Angelo were so busy accommodating tourists they had no time to appear in the film; extras were brought in from a neighboring village.[5]

Simon lamented that De Sica insisted on using his own film editors—two individuals who did not speak English and thus did not understand the jokes.[5] The film was later re-cut in Rome by one of John Huston's favorite film editors, Russell Lloyd, but Simon believes more funny bits "are lying in a cutting room in Italy". (Apparently there was a deleted scene where Vanucci impersonated one of the Beatles.[11]) The voices and accents of the Italian comic actors were dubbed in London, mainly by Robert Rieti and edited in Rome by Malcolm Cooke, who had been a post-sync dialogue editor on Lawrence of Arabia.[citation needed]

Simon summed up his opinion of the film: "to give the picture its due, it was funny in spots, innovative in its plot, and was well-intentioned. But a hit picture? Uh-uh ... Still today, After the Fox remains a cult favorite."[5]

Burt Bacharach composed the score and with lyricist Hal David wrote the title song for the film. For the Italian release, the score was composed by Piero Piccioni.[12] The title song "After the Fox" was recorded by The Hollies with Sellers in August 1966 and released by United Artists as a single (b/w "The Fox-Trot").[13][14]

Release[]

After the Fox was released in Great Britain, Italy and the United States in December 1966.[15] As part of a publicity barrage, United Artists announced that it had signed Federico Fabrizi to direct three films. The story was to be planted in the trade papers and then appear in general newspapers, with Sellers available for telephone interviews in character as Fabrizi. The editors of Daily Variety recognized the fictional name immediately, however, and spoiled the gag.[16]

The film received mixed reviews. The New York Times critic Bosley Crowther summed up his review, "It's pretty much of a mess, this picture. Yes, you'd think it was done by amateurs".[4]

The Variety reviewer thought "Peter Sellers is in nimble, lively form in this whacky comedy which, though sometimes strained, has a good comic idea and gives the star plenty of scope for his usual range of impersonations".[17]

The Boston Globe termed the film "funny, fast and wholly ridiculous", and thought Sellers' portrayal of Fabrizi "hilarious."[18]

Billboard called the film "a series of fun-filled satires...guaranteed for laughs", and thought Sellers was "at his droll best" and Mature "hilarious."[19]

Monthly Film Bulletin, however, wrote, "Continuing the De Sica's decline of recent years, this witless comedy of incompetent crooks and excitable Italians never even begins to get off the ground", and called Seller's performance "self-indulgent", but singled out Mature as "amusing and touching."[20]

Opinion continues to be divided. After the Fox is rated 6.5/10 on IMDB, an average of more than 2,500 user ratings. The review aggregator Web site Rotten Tomatoes reported a 71% approval rating with an average rating of 5.6/10, based on seven reviews.[21]

The film has some kinship with What's New Pussycat?, which was released the previous year and also starred Sellers. That film was the first written by Woody Allen who, like Neil Simon, had been a staff writer for Sid Caesar. Even the advertising tagline on the posters and trailer for After The Fox proclaimed, "You Caught The Pussycat ... Now Chase The Fox!".[6] The poster art for both films was illustrated by Frank Frazetta.[22]

Influence[]

The device in which robbers use a movie set to cover a robbery is also in Woody Allen's Take the Money and Run (1969). In the television series Batman, it is used in the 1968 episode titled "The Great Train Robbery".

The scene in the film where Aldo speaks to Okra through the beautiful Maria Grazia Buccella inspired a similar scene in Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002), in which Austin Powers talks to Foxxy Cleopatra through the Nathan Lane character.[citation needed]

The 2010 Bollywood film Tees Maar Khan is an official remake of After the Fox.[23]

References[]

- ^ "Big Rental Films of 1967", Variety, 3 January 1968, p. 25.

- ^ Erickson, Hal. "After the Fox: Overview". AllMovie. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ https://www.rediff.com/movies/report/tees-maar-khan-is-an-official-remake/20101222.htm

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crowther, Bosley (24 December 1966). "After the Fox (1966). Screen: 'After the Fox': First Neil Simon Film Has Local Premiere". The New York Times. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Simon, Neil (1996). "La Dolce Vita". Rewrites: A Memoir. ISBN 0-684-82672-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c McKay, James (2012). The Films of Victor Mature. McFarland. pp. 20, 165–166. ISBN 978-0-7864-4970-5.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (7 December 1966). "Victor Mature Hits Stride". Los Angeles Times. p. D15.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (7 December 1966). "Victor Mature Hits Stride". Los Angeles Times. p. D15.

- ^ Chicago Tribune, Jan 15, 1967.

- ^ "Production Notes – Thunderball". MI6. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ "The Faces Of Sellers", The Baltimore Sun, 1 Aug. 1965

- ^ Spencer, Kristopher (2008). Film and Television Scores, 1950–1979: A Critical Survey by Genre. McFarland. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-7864-5228-6.

- ^ Strong, Martin Charles (2002). The Great Rock Discography. Canongate. p. 495. ISBN 978-1-84195-312-0.

- ^ Neely, Tim; Popoff, Martin (2009). Goldmine Price Guide to 45 RPM Records. Krause. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-89689-958-2.

- ^ Munden, Kenneth White (1997). The American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures Produced in the United States. University of California Press. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-520-20970-1.

- ^ "Hocus Pocus Vs. Pokus-Hoaxers on UA's Fabrizi", Variety, 23 Nov. 1966

- ^ Variety staff (31 December 1965). "Review: After the Fox". Variety. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ Boston Globe; Dec 16, 1966; p. 38

- ^ Boxoffice, Dec 12, 1966.

- ^ Monthly Film Bulletin. 33 (384). London. 1 January 1966. p. 168. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ "After the Fox (1966)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- ^ Booker, M. Keith (2014). Comics through Time: A History of Icons, Idols, and Ideas. ABC-CLIO. p. 587. ISBN 978-0-313-39751-6.

- ^ "It's official: Tees Maar Khan is a remake". Rediff.com. 22 December 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2010.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: After the Fox |

- After the Fox at IMDb

- After the Fox at AllMovie

- After the Fox at the TCM Movie Database

- 1966 films

- 1960s crime comedy films

- 1960s multilingual films

- English-language films

- Italian-language films

- British films

- British crime comedy films

- Italian films

- Commedia all'italiana

- Italian crime comedy films

- Films directed by Vittorio De Sica

- Films with live action and animation

- Films with screenplays by Neil Simon

- Films with screenplays by Cesare Zavattini

- Films about con artists

- Italian heist films

- Films scored by Burt Bacharach

- Films set in the Mediterranean Sea

- United Artists films

- British multilingual films

- Italian multilingual films

- 1966 comedy films

- English-language Italian films