Alberto Fernández

Alberto Fernández | |

|---|---|

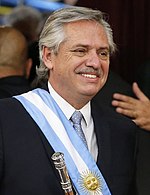

Fernández in 2020 | |

| President of Argentina | |

| Assumed office 10 December 2019 | |

| Vice President | Cristina Fernández de Kirchner |

| Preceded by | Mauricio Macri |

| Chief of the Cabinet of Ministers | |

| In office 25 May 2003 – 23 July 2008 | |

| President | Néstor Kirchner Cristina Fernández de Kirchner |

| Preceded by | Alfredo Atanasof |

| Succeeded by | Sergio Massa |

| Member of the Buenos Aires City Legislature | |

| In office 7 August 2000 – 25 May 2003 | |

| Superintendent of Insurance | |

| In office 1 August 1989 – 8 December 1995 | |

| President | Carlos Menem |

| Preceded by | Diego Peluffo |

| Succeeded by | Claudio Moroni |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Alberto Ángel Fernández 2 April 1959 Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Political party | Justicialist Party (1983–present) |

| Other political affiliations | UNIR Constitutional Nationalist Party (1982–1983) |

| Spouse(s) | Marcela Luchetti

(m. 1993; div. 2005) |

| Domestic partner | Fabiola Yáñez (2014–present)[1] |

| Children | 1 |

| Residence | Quinta presidencial de Olivos |

| Alma mater | University of Buenos Aires |

| Signature | |

Alberto Ángel Fernández (Spanish pronunciation: [alˈβeɾto ferˈnandes]; born 2 April 1959) is an Argentine politician, lawyer and professor, serving as President of Argentina since 2019.

Born in Buenos Aires, Fernández attended the University of Buenos Aires, where he earned his law degree at the age of 24, and later became a professor of criminal law. He entered public service as an adviser to Deliberative Council of Buenos Aires and the Argentine Chamber of Deputies. In 2003, he was appointed Chief of the Cabinet of Ministers, serving during the entirety of the presidency of Néstor Kirchner, and the early months of the presidency of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

A member of the center-left peronist[2] Justicialist Party, Fernández was the party's candidate for 2019 presidential election, defeating incumbent president Mauricio Macri, with 48% of the votes. He started his presidency a few months before the COVID-19 pandemic in Argentina.

In foreign policy, during early months of his presidency, Fernández saw an Argentina's relationship straining with Brazil due to political rhetoric rivalry with Brazil's president Jair Bolsonaro.[3] He questioned the conclusions of the Organization of American States that the reelection of Evo Morales was unconstitutional for electoral fraud.[4]

Early life and career[]

Fernández was born in Buenos Aires, son of Celia Pérez and her first husband. Separated from the latter, Celia (sister of the personal photographer of Juan Domingo Perón) married Judge Carlos Pelagio Galíndez (son of a Senator of the Radical Civic Union).[5] Alberto Fernández, who barely knew his biological father, considers Pelagio to be his father.[5][6]

Alberto Fernández attended Law School at the University of Buenos Aires. He graduated at the age of 24, and later became a professor of criminal law. He entered public service as an adviser to Deliberative Council of Buenos Aires and the Argentine Chamber of Deputies. He became Deputy Director of Legal Affairs of the Economy Ministry, and in this capacity served as chief Argentine negotiator at the GATT Uruguay Round. Nominated by newly elected President Carlos Menem to serve as Superintendent of Insurance, Fernández served as President of the Latin American Insurance Managers' Association from 1989 to 1992, and co-founded the Insurance Managers International Association. He also served as adviser to Mercosur and ALADI on insurance law, and was involved in insurance and health services companies in the private sector. Fernández was named one of the Ten Outstanding Young People of Argentina in 1992, and was awarded the Millennium Award as one of the nation's Businessmen of the Century, among other recognitions.[7] During this time he became politically close to former Buenos Aires Province Governor Eduardo Duhalde.[8]

He was elected on 7 June 2000, to the Buenos Aires City Legislature on the conservative Action for the Republic ticket led by former Economy Minister Domingo Cavallo.

Chief of the Cabinet (2003–2008)[]

He gave up his seat when he was appointed Chief of the Cabinet of Ministers by President Néstor Kirchner upon taking office on 25 May 2003, and retained the same post under Kirchner's wife and successor, President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, upon her election in 2007.[9][10]

A new system of variable taxes on agricultural exports led to the 2008 Argentine government conflict with the agricultural sector, during which Fernández acted as the government's chief negotiator. The negotiations failed, however, and following Vice President Julio Cobos' surprise, tie-breaking vote against the bill in the Senate, Fernández resigned on 23 July 2008.[11]

Pre-presidency[]

He was named head of the City of Buenos Aires chapter of the Justicialist Party, but minimized his involvement in Front for Victory campaigns for Congress in 2009.[12] Fernández actively considered seeking the Justicialist Party presidential nomination ahead of the 2011 general elections.[13] He ultimately endorsed President Cristina Kirchner for re-election, however.[14] He was campaign manager of the presidential candidacy of Sergio Massa in 2015.[15]

Presidential elections[]

Presidential campaign[]

On 18 May 2019, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner announced that Fernández would be a candidate for president, and that she would run for vice president alongside him, hosting his first campaign rally with Santa Cruz Governor Alicia Kirchner, sister-in-law of the former Kirchner.[16][17]

About a month later, seeking to broaden his appeal to moderates, Fernández struck a deal with Sergio Massa to form an alliance called Frente de Todos, wherein Massa would be offered a role within a potential Fernández administration, or be given a key role within the Chamber of Deputies in exchange for dropping out of the presidential race and offering his support.[18] Fernández also earned the endorsement of the General Confederation of Labor, receiving their support in exchange for promising that he will boost the economy, and that there will be no labor reform.[19]

General elections[]

On 11 August 2019, Fernández won first place in the 2019 primary elections, earning 47.7% of the vote, compared to incumbent President Mauricio Macri's 31.8%.[20] Fernández thereafter held a press conference where he said he called Macri to say that he would help Macri complete his term and "bring calm to society and markets," and that his economic proposals do not run the risk of defaulting on the national debt.[21]

In the 27 October general election, Fernández won the presidency by attaining 48.1% of the vote to Macri's 40.4%, exceeding the threshold required to win without the need for a ballotage. [22] In Argentina, a presidential candidate can win outright by either garnering at least 45 percent of the vote, or winning 40 percent of the vote while being 10 points ahead of his or her nearest challenger. He owed his victory mainly to carrying Buenos Aires Province by over 1.6 million votes, accounting for almost all of his nationwide margin of 2.1 million votes. By comparison, Daniel Scioli only carried the country's largest province by 219,000 votes four years earlier.

Presidency[]

| Presidential styles of Alberto Fernández | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | Excelentísimo Señor Presidente de la Nación (Most Excellent President of the Nation) |

| Spoken style | Presidente de la Nación (President of the Nation) |

| Alternative style | Señor Presidente (Mister President) |

Inauguration[]

Fernández was sworn in on 10 December 2019.

Economic policy[]

On 14 December, the government established by decree the emergency in occupational matters and double compensation for dismissal without just cause for six months.[23]

His first legislative initiative, the Social Solidarity and Productive Recovery Bill, was passed by Congress on 23 December.[24] The bill includes tax hikes on foreign currency purchases, agricultural exports, wealth, and - as well as tax incentives for production. Amid the worst recession in nearly two decades, it provides a 180-day freeze on utility rates, bonuses for the nation's retirees and Universal Allocation per Child beneficiaries, and food cards to two million of Argentina's poorest families. It also gave the president additional powers to renegotiate debt terms – with Argentina seeking to restructure its US$100 billion debt with private bondholders and US$45 billion borrowed by Macri from the International Monetary Fund.[24] As the capital controls stayed in effect and with no prospect of being removed, the degraded the country from emerging market to standalone market.[25]

Organizations of the agricultural sector, including Sociedad Rural Argentina, CONINAGRO, Argentine Agrarian Federation and Argentine Rural Confederations, rejected the increase in taxes on agricultural exports. Despite these conflicts, Fernández announced the three-point increase in withholding tax on soybeans on the day of the opening of the regular sessions, on 1 March and generated major problems in the relationship between the government and the agricultural sector.[26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][excessive citations]

Argentina defaulted again on May 22, 2020 by failing to pay $500 million on its due date to its creditors. Negotiations for the restructuring of $66 billion of its debt continue.[34]

The International Monetary Fund reported that the COVID-19 crisis would plunge Argentina's GDP by 9.9 percent, after the country's economy contracted by 5.4 percent in first quarter of 2020, with unemployment rising over 10.4 percent in the first three months of the year, before the lockdown started.[35][36][37]

On August 4, Fernández reached an accord with the biggest creditors on terms for a restructuring of $65bn in foreign bonds, after a breakthrough in talks that had at times looked close to collapse since the country's ninth debt default in May.[38]

On September 22, as part of the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, official reports showed a 19% year-on-year drop in the GDP for the second quarter of 2020, the biggest drop in the country's history.[39][40] Investment went down 38% from the previous year.[39][40] The poverty rate rose to 42% in the second half of 2020, the highest since 2004.[41] Child poverty reaches the 57.7% of minors of 14 years.[41]

Social policy[]

On 31 December 2019, Fernández announced that he will send a bill in 2020 to discuss the legalization of abortion, ratified his support for its approval, and expressed his wish for "sensible debate".[42] However, in June 2020, he stated that he was "attending to more urgent matters" (referring to the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the debt restructuring), and that "he'll send the bill at some point".[43] In November 2020, Fernández's legal secretary, Vilma Ibarra, confirmed that the government would be sending a new bill for the legalization of abortion to the National Congress that month.[44] The Executive sent the bill, alongside another bill oriented towards women's health care (the "1000 Days Plan"), on 17 November 2020.[45] The bill was passed by the Senate, legalizing abortion in Argentina, on 30 December 2020.[46]

On 1 March, he also announced a restructuring of the Federal Intelligence Agency (AFI), including the publications of its accounts - which had been made secret by Macri in a 2016 decree.[47][48] The AFI had been criticized for targeting public figures for political purposes.[47]

On August 17, protests took place in many cities across Argentina against measures taken by Fernández, primarily the Justice Reform Bill his government had sent to the Congress, but also, among other causes: for the "defense of institutions" and "separation of powers", against the government's quarantine measures, the perceived lack of liberty and the increase in crime, and a raise on state pensions.[49][50]

On 4 September 2020, Fernández signed a Necessity and Urgency Decree (Decreto 721/2020) establishing a 1% employment quota for trans and travesti people in the national public sector. The measure had been previously debated in the Chamber of Deputies as various prospective bills.[51] The decree mandates that at any given point, at least 1% of all public sector workers in the national government must be transgender, as understood in the 2012 Gender Identity Law.[52]

On 20 July 2021, Fernández signed another Necessity and Urgency Decree (Decreto 476/2021) mandating the National Registry of Persons (RENAPER) to allow a third gender option on all national identity cards and passports, marked as an "X". The measure applies to non-citizen permanent residents who possess Argentine identity cards as well.[53] In compliance with the 2012 Gender Identity Law, this made Argentina one of the few countries in the world to legally recognize non-binary gender on all official documentation.[54][55]

On 12 November 2020 Fernández signed a decree legalizing the self-cultivation and regulating the sales and subsidized access of medical cannabis, expanding upon a 2017 bill that legalized the use and research of the plant and its derivatives.[56] In June 2019, during his presidential campaign, he had signaled his intention to legalize marijuana for recreational purposes, but not other types of drugs.[57]

Foreign relations[]

During his administration, Argentina's relationship with Brazil has become somewhat strained.[3] Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro refused to attend Fernández's inauguration, accusing him of wanting to create a "great Bolivarian homeland" on the border and of preparing to provoke a flight of capital and companies into Brazil.[58] Fernández and Bolsonaro had their first conversation through a video conference on 30 November 2020, during which both presidents agreed on the importance of cooperation and the role of Mercosur.[59]

Donald Trump's top adviser for the Western Hemisphere, Mauricio Claver-Carone, crossed Fernández in 2019 saying: "We want to know if Alberto Fernández will be a defender of democracy or an apologist for dictatorships and leaders in the region, whether it be Maduro, Correa or Morales."[60]

Under Fernández, Argentina has retired in the Lima Group formed by North and South American nations to address the crisis in Venezuela, after not subscribing to any of the Group's statements and resolutions.[61] Argentina voted in favor of the United Nations resolution to back the continuity of the UN Human Rights Office report on human rights violations in Venezuela.[62] Under Fernández, Argentina withdrew recognition of Juan Guaidó as interim President of Venezuela.[63] In January 2020, the Fernández administration revoked Elisa Trotta Gamus credentials, who was Guaidó's envoy to Argentina and whose representation had been approved by the Macri administration.[64] However, Fernández also refused to recognize Maduro's envoy Stella Lugo's credentials and Foreign Minister Felipe Solá asked her to return to Caracas.[65][66]

Alberto Fernández questioned the conclusions the Organization of American States that the reelection of Evo Morales was unconstitutional for electoral fraud. Fernández's government recognized Morales as the legitimate President of Bolivia, and granted him asylum in Argentina in December 2019.[4][67] On 9 November 2020, with the Luis Arce's victory in 2020, Fernández personally accompanied Morales to the Argentine border with Bolivia, wherein the two leaders held a public act celebrating Morales's return to his home country.[68]

In January 2020, Fernández traveled to Israel for his first presidential trip abroad. There he paid respects to the victims of the Holocaust and maintained a bilateral meeting with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu who thanked him for keeping Hezbollah branded as a terrorist organization, a measure taken by former President Mauricio Macri.[69][70]

Regarding Argentina's strained relations with Iran, Fernández publicly defended the Memorandum of understanding between Argentina and Iran,[71] although critical of this prior to taking office.[72] In September 2020, Fernández asked Iran before the UN General Assembly to "cooperate with the Argentine justice" to bring justice to the cause and extradite those Iranian officials who stand accused of the attack. He further stated that if the officials were to be found innocent, "they could freely return to Iran or otherwise face the consequences for their actions."[71][73]

Position during COVID-19 pandemic and measures[]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Fernandez's government announced a country-wide lockdown, in effect from 20 March until 31 March, later extended until 12 April.[75][76] The lockdown was further renewed on April 27, May 11, May 25, June 8, July 1, July 18, August 3, August 17, August 31 and September 21, and included several measures including travel, transport and citizen movement restrictions, stay-at-home orders, store closures and reduced operating hours.[77]

Responses to the outbreak have included restrictions on commerce and movement, closure of borders, and the closure of schools and educational institutions.[78] The announcement of the lockdown was generally well received, although there were concerns with its economic impact in the already delicate state of Argentina's economy, with analysts predicting at least 3% GDP decrease in 2020.[79][80] Fernandez later announced a 700 billion pesos (US$11.1 billion) stimulus package, worth 2% of the country's GDP.[81][82][79] After announced a mandatory quarantine to every person that returned to Argentina from highly affected countries,[83][84] the government closed its borders, ports, and suspended flights.[78][85]

On 23 March, Fernández asked the Chinese president Xi Jinping for 1,500 ventilators as Argentina had only 8,890 available.[86][87]

Included in the package was the announcement of a one-time emergency payment of 10,000 pesos (US$152, as of March 20) to lower-income individuals whose income was affected by the lockdown, including retirees.[88] Because banks were excluded in the list of businesses that were considered essential in Fernandez's lockdown decree, they remained closed until the Central Bank announced banks would open during a weekend starting on 3 April.[89]

Due to Argentina's notoriously low level of banking penetration, many Argentines, particularly retirees, do not possess bank accounts and are used to withdraw funds and pensions in cash.[90] The decision to open banks for only three days on a reduced-hours basis sparked widespread outrage as hundreds of thousands of retirees (coronavirus' highest risk group) flocked to bank branches in order to withdraw their monthly pension and emergency payment.[91][92][93][94]

Due to the national lockdown, the economical activity suffered a collapse of nearly 10% in March 2020 according to a consultant firm. The highest drop was of the construction sector (32%) versus March 2019. Every economical sector suffered a collapse, with finance, commerce, manufacturing industry and mining being the most affected. The agriculture sector was the least affected, but overall the economic activity for the first trimester of 2020 accumulates a 5% contraction. It is expected that the extension of the lockdown beyond April would increase the collapse of the Argentinian economy.[95] On March, the primary fiscal deficit jumped to US$1,394 million, an 857% increase year-to-year. This was due to the public spending to combat the pandemic and the drop in tax collection due to low activity in a context of social isolation.[96] Schools were closed for over a year, and it is estimated that 1.5 million of kids abandoned school, a 13% of the total.[97]

Despite the government's hard lockdown policy, Fernández has been harshly criticized [98] for not following the appropriate protocols himself. This included traveling throughout the country, taking pictures with large groups of supporters without properly wearing a mask nor respecting social distancing,[99] and holding social gatherings with union leaders.[100]

On September 3, despite most local governments still enforcing strict lockdown measures, Fernández stated that "there is no lockdown",[101] and that such thoughts had "been instilled by the opposition", as part of a political agenda.[102] Fernández eased some lockdown measures in the Greater Buenos Aires on November 6, 2020, shifting to a "social distancing" phase.[103][104]

On 21 January 2021, Fernández became the first Latin American leader to be inoculated against the disease via the recently approved Gam-COVID-Vac (better known as Sputnik V).[105][106]

Ginés González García was forced to resign as Health Minister on 19 February 2021[107] after it was revealed he provided preferential treatment for the COVID-19 vaccine to his close friends, including journalist Horacio Verbitsky and other political figures. He was succeeded by the second in charge Carla Vizzotti. The revelation was met with wide national condemnation from supporters and opposition, as Argentina had at the time received only 1,5 million [108] doses of vaccine for its population of 40 million.[109]

Fernández tested positive for the COVID-19 on 2 April 2021 having a "light fever".[110]

Justicialist Party chairmanship[]

On 22 March 2021, Fernández was elected by the national congress of the Justicialist Party as the party's new national chairman, succeeding José Luis Gioja.[111] Fernández ran unopposed, heading the Unidad y Federalismo list, which received the support of diverse sectors in the Peronist movement, including La Cámpora.[112]

Controversies[]

Fernández has engaged in disputes with users on Twitter before his presidency, in which his reactions have been regarded as aggressive or violent by some.[113][114][115]

Tweets show him responding to other users with expletives such as "pelotudo" (Argentinian slang for "asshole"),[116][117] "pajero" ("wanker"),[118][114] and "hijo de puta" ("son of a bitch"),[119][120] He also called presidential candidate José Luis Espert "Pajert", a word play between his last name and the Argentine slang for "wanker".[117]

In December 2017, he responded to a female Twitter user by saying, "Girl, what you think doesn't worry me. You better learn how to cook. Maybe then you can do something right. Thinking is not your strong suit".[121][122]

In June 2020, he told journalist Cristina Pérez to "go read the Constitution", after being questioned about his attempts to install a government-designated administration in the Vicentín agricultural conglomerate.[123]

In a 2017 interview for the Netflix mini-series Nisman: The Prosecutor, the President, and the Spy, Fernández stated that "To this day, I doubt that he (Nisman) committed suicide";[124] however, after he became president in 2020, Fernández reportedly said, "I am convinced that it was a suicide, after doubting it a lot, I am not going to lie."[125] He was referring to Alberto Nisman, a prosecutor investigating Fernández's vice president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner for her suspected cover-up of Iran's participation in the 1994 AMIA bombing. Nisman accused Fernández de Kirchner of secretly negotiating with Iranian officials to cover up their complicity in the attack in exchange for oil to reduce Argentina's energy deficit. Officially, the agreement called for the exchange of Argentinian grain for Iranian oil.[126] Nisman was found dead in his apartment on January 18, 2015, only hours before he was scheduled to present his report to Congress.[127]

On 9 June 2021, Alberto Fernández was at a meeting with business leaders alongside Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez at the Casa Rosada. When he sought to play up the Argentinian ties with Europe, he said “The Mexicans came from the Indians, the Brazilians came from the jungle, but we Argentines came from the ships. And they were ships that came from Europe.” Fernández erroneously attributed the quote to the Mexican poet, essayist and diplomat Octavio Paz, when it was about lyrics by local musician and personal friend Litto Nebbia. Faced with the negative backlash to his comments, on the same day Fernández apologized on Twitter[128] and the next day sent a letter to the director of the National Institute Against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism (INADI), clarifying his comments.[129]

In August 2021, it was revealed that there had been numerous visits to the presidential palace during the lockdown that he had imposed in early 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic; visitors included an actress, a dog trainer, and a hairdresser, as well as hosting a birthday party for his girlfriend.[130][131]

Personal life[]

Fernández married a fellow University of Buenos Aires law student, Marcela Luchetti, in 1993.[132] They separated in 2005.[133] Fernández and Luchetti have a single child, Tani Fernández Luchetti (born 1994),[134] known in Argentina for being a drag performer and cosplayer who goes by the stage name Dyhzy.[135][136]

Fernández is a supporter of Argentinos Juniors' football team.[137]

Since 2014, Fernández has been in a relationship with journalist and stage actress Fabiola Yáñez, who has fulfilled the role of First Lady of Argentina since Fernández's presidency began.[1] The couple own three dogs: Dylan[138] (named after Bob Dylan, whom Fernández has praised and cited as an inspiration[139]) and two of Dylan's puppies, Prócer[140] and Kaila.[141]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Fabiola Yáñez, la novia de Alberto Fernández: 'Él no quería ser candidato'". Perfil. 26 August 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/dec/10/argentina-alberto-fernandez-inauguration

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ochoa, Raúl (17 February 2020). "Argentina-Brasil: incierto escenario para una relación indispensable". Clarín (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Alberto Fernández defendió la legitimidad de la reelección de Evo Morales en Bolivia". Diario La Nación. 29 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b 20minutos (28 October 2019). "Perfil | Alberto Fernández, el elegido de Cristina que logró llegar a la Presidencia". http://www.20minutos.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ "La historia de Alberto Fernández: de Villa del Parque a la Rosada, con una guitarra y la política a cuestas". www.ambito.com. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- ^ "Clase Magistral". Universidad Nacional de San Luis. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013.

- ^ "El Pasado Menemista de un gobierno que acusa a la oposición de menemista". Perfil. Archived from the original on 17 April 2008.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández habría vuelto con su esposa". Agencia Nova. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández y Vilma Ibarra más juntos que nunca". Perfil. 26 August 2019. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández presentó su renuncia para "dar libertad" a Cristina". Clarín (in Spanish). 23 July 2008. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Kirchner cargó contra Cobos y De Narváez en un acto porteño". Clarín (in Spanish). 16 June 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández reiteró que no descarta ser candidato a presidente en 2011". La Nación (in Spanish). 24 March 2010. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández se declara oficialista y ya se anota como candidato para 2015". La Nación. 30 August 2011. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández: "Es indudable el deterioro en el voto de Sergio Massa"". Minuto Uno (in Spanish). 2 June 2015. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández presidente, Cristina Kirchner vice: el video en el que la senadora anuncia la fórmula". La Nación. 18 May 2019.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández, en su primer acto de campaña: "Salgamos a convocar a todos"". La Nacion (in Spanish). 20 May 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "Argentina's Massa in line for key Congress role on Fernandez presidential ticket". Reuters. 18 June 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Bullrich, Lucrecia (17 July 2019). "Alberto Fernández recibió el respaldo de la CGT y dijo que no hará reformas" (in Spanish). La Nación. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Mander, Benedict (12 August 2019). "Alberto Fernández leads in Argentina's nationwide primary". Financial Times. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández: "El Presidente tiene que llegar al 10 de diciembre"" (in Spanish). La Nacion. 14 August 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Goñi, Uki (28 October 2019). "Argentina election: Macri out as Cristina Fernández de Kirchner returns to office as VP". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández firmó un DNU que establece la doble indemnización por seis meses". Diario La Nación. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Fernández's economic emergency law wins approval in Senate". Buenos Aires Times. 23 December 2019.

- ^ Vinicius Andrade and Jorgelina Do Rosario (24 June 2021). "Argentina Shares Fall After MSCI Cuts Emerging Market Status". Bloomberg. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ "El Gobierno cambió el esquema de retenciones y decidió aumentarlas". Diario La Nación. 15 December 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ "Suba de retenciones. Los productores se movilizaron y en algunos lugares ya piden medidas de fuerza". Diario La Nación. 16 December 2019.

- ^ "Hoy y mañana. En el norte el campo hará un cese de comercialización por 48 horas". Diario La Nación. 19 December 2019.

- ^ "Subirían tres puntos las retenciones a la soja y se tensa el vínculo con el campo". Diario La Nación. 23 February 2020.

- ^ "Retenciones. Productores proponen un paro de 15 días y una rebelión fiscal". Diario La Nación. 1 March 2020.

- ^ "Crece la tensión entre el campo y el Gobierno por la eventual suba de retenciones". Diario La Nación. 24 February 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández: "Es muy violento el paro del campo"". Diario La Nación. 10 March 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández criticó el paro del campo y advirtió: "No nos van a hacer cambiar el rumbo"". Diario La Nación. 10 March 2020.

- ^ Politi, Daniel (22 May 2020). "Argentina Tries to Escape Default as It Misses Bond Payment". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ "IMF predicts Argentina's economy will slump 9.9% in 2020". Buenos Aires Time (Perfil). 25 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "INDEC: Economy contracted by 5.4% in first quarter of 2020". Buenos Aires Time (Perfil). 23 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "IMF predicts deeper global recession due to coronavirus pandemic". Reuters. 24 June 2020. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Argentina strikes debt agreement after restructuring breakthrough". Financial Times. 4 August 2020. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Informe de avance del nivel de actividad - Segundo trimestre de 2020" [Activity Level Report - Second Quarter 2020] (PDF). Informes técnicos (in Spanish). National Institute of Statistics and Census of Argentina. 4 (172). September 2020. ISSN 2545-6636.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gillespie, Patrick (22 September 2020). "Argentina's Economy Slumps 16.2%, Narrowly Beating Forecasts". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Pandemic and economic crisis pushes poverty rate up to 42%". Buenos Aires Times. 31 March 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández confirmó que enviará en 2020 el proyecto para legalizar el aborto". Infobae.com. 31 December 2019.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández, sobre la legalización del aborto: "Ahora tengo otras urgencias"". Clarin.com. 2 June 2020.

- ^ Carbajal, Mariana (10 November 2020). "Aborto legal: el Gobierno enviará el proyecto al Congreso durante noviembre". Página/12 (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ Carbajal, Mariana (17 November 2020). "Aborto legal: Alberto Fernández enviará hoy el proyecto al Congreso". Página/12 (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- ^ Goñi, Uki; (30 December 2020). "Argentina legalises abortion in landmark moment for women's rights: Country becomes only the third in South America to permit elective abortions". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Fernández taps Caamaño to lead overhaul of AFI intelligence agency". Buenos Aires Times. 20 December 2019.

- ^ "Argentina's spy agency regroups, wins back power under Macri". Reuters. 20 July 2016. Archived from the original on 21 July 2016.

- ^ "LIVE: Crowds in Buenos Aires rally against quarantine measures in Argentina". Reuters. 17 August 2020.

- ^ "Anti-government protesters defy virus measures in Argentina". France 24. 18 August 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- ^ "Por decreto, el Gobierno estableció un cupo laboral para travestis, transexuales y transgénero". Infobae (in Spanish). 4 September 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "El Gobierno decretó el cupo laboral trans en el sector público nacional". La Nación (in Spanish). 4 September 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2020.

- ^ "Decreto 476/2021". Boletín Oficial de la República Argentina (in Spanish). 20 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández pondrá en marcha el DNI para personas no binarias". Ámbito (in Spanish). 20 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Identidad de género: el Gobierno emitirá un DNI para personas no binarias". La Nación (in Spanish). 21 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ Hasse, Javier (12 November 2020). "Argentina Regulates Medical Cannabis Self-Cultivation, Sales, Subsidized Access". Forbes. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández, sobre el consumo de marihuana: "No tenemos que perseguir a los fumadores de porro"". La Nación (in Spanish). 18 June 2019. Retrieved 13 November 2020.

- ^ "Jair Bolsonaro: "Quiero una Argentina fuerte, no una patria bolivariana"". Infobae (in Spanish). 13 February 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Niebieskikwiat, Natasha (30 November 2020). "Alberto Fernández mantuvo su primera conversación con Jair Bolsonaro: "La única diferencia que tenemos es en el fútbol"". Clarín (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Clarín.com. "Durísimo mensaje de EE.UU contra Alberto F: "Queremos saber si va a ser abogado de la democracia o apologista de las dictaduras"". www.clarin.com (in Spanish).

- ^ Dinatale, Martín (13 October 2020). "La Argentina permanecerá en el Grupo Lima pero rechazará una declaración contra Venezuela". Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Argentina votó a favor del informe de Bachelet y volvió a condenar el bloqueo a Venezuela". Télam (in Spanish). 6 October 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ "Foreign Ministry withdraws 'special' status granted to Guaidó's envoy". Buenos Aires Times. 7 January 2020.

- ^ "El Gobierno le quitó las credenciales a Elisa Trotta, la embajadora de Juan Guaidó en Argentina" [The Government revoked the credentials of Elisa Trotta, Juan Guaidó's ambassador in Argentina]. Clarín. 7 January 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández rechaza a Stella Lugo como embajadora de Maduro en Argentina" [Alberto Fernández rejects Stella Lugo as Maduro's ambassador in Argentina]. Diario Las Americas (in Spanish). 13 January 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández rechazó a Stella Lugo como embajadora de Maduro en Argentina" [Alberto Fernández rejected Stella Lugo as Maduro's ambassador in Argentina]. El Nacional (in Spanish). 13 January 2020.

- ^ "Evo Morales granted refugee status in Argentina". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández acompañó a Evo Morales hasta la frontera con Bolivia y dejó un mensaje". La Nación (in Spanish). 9 November 2020. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- ^ Lejtman, Román (24 January 2020). "Alberto Fernández, a Netanyahu: "Nuestro compromiso por saber la verdad de lo que pasó en la AMIA es absoluto"". Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ "Benjamin Netanyahu felicitó a Alberto Fernández por mantener la postura contra Hezbollah". Perfíl (in Spanish). 24 January 2020. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Niebieskikwiat, Natasha (16 July 2020). "Alberto Fernández defendió el Memorándum con Irán por la Causa AMIA" [Alberto Fernández defended the Memorandum with Iran for the AMIA Cause]. Clarín (in Spanish).

- ^ Cappiello, Hernán (16 July 2020). "El giro de Alberto Fernández: qué decía antes y qué dice hoy de Cristina Kirchner y el memorándum con Irán" [Alberto Fernández's turn: what he said before and what he says today about Cristina Kirchner and the memorandum with Iran]. La Nación (in Spanish).

- ^ "Alberto Fernández en la ONU: "Le pido a Irán que coopere con la justicia argentina para avanzar en la investigación del atentado a la AMIA"" [Alberto Fernández at the UN: "I ask Iran to cooperate with the Argentine justice to advance the investigation of the AMIA attack"]. Infobae (in Spanish). 22 September 2020.

- ^ Mander, Benedict (23 March 2020). "Pandemic throws Argentina debt strategy into disarray". Financial Times.

- ^ Do Rosario, Jorgelina; Patrick, Gillespie. "Argentina Orders 'Exceptional' Lockdown in Bid to Stem Virus". Bloomberg. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Squires, Scott; Patrick, Gillespie. "Argentina Says It Aims to Avoid Default Amid Lockdown Extension". Bloomberg. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Costa, José María (9 October 2020). "Covid: las 18 provincias que tendrán aislamientos de 14 días en algunas zonas". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 October 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Argentina to close borders for non-residents to combat coronavirus". Reuters. 15 March 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mander, Benedict. "Pandemic throws Argentina debt strategy into disarray". Financial Times. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Rapoza, Kenneth. "Argentina Goes Under Quarantine As Debt Deal Now An Afterthought". Forbes. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Meakin, Lucy (20 March 2020). "Cash and Low Rates: How G-20 Policy-Makers Are Stepping Up". National Post. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Newbery, Charles. "Argentina unveils $11 bln stimulus package". LatinFinance. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus en Argentina: será obligatoria la cuarentena para quienes regresen de los países más afectados". Clarín (in Spanish). 11 March 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "Cuarentena por coronavirus: cuáles son los países de riesgo para los viajeros que vuelven a la Argentina". Clarín (in Spanish). 9 March 2020. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- ^ "El Gobierno cierra fronteras, aeropuertos y puertos por el coronavirus: la veda alcanza a los argentinos". Clarín (in Spanish). 26 March 2020.

- ^ Ruiz, Iván; Arambillet, Delfina (24 April 2020). "Coronavirus en la Argentina: pocas donaciones, muchas compras y el inicio de un malestar con China". La Nación (in Spanish).

- ^ "Coronavirus: el Gobierno le pide ayuda a China para conseguir más respiradores". La Nación (in Spanish). 23 March 2020.

- ^ Sigal, Lucila (23 March 2020). "Argentina offers spot payments to coronavirus-hit low income workers". Reuters. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "En medio de la cuarentena total, hoy abren los bancos: quiénes pueden ir y cómo van a funcionar". Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Raszewski, Eliana; Lobianco, Miguel (3 April 2020). "'Ridiculous' block-long lines at banks greet Argentine pensioners, at high risk for coronavirus". Reuters. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ Doll, Ignacio Olivera. "Argentines disobey virus lockdown to collect money from banks". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Indignados y enojados: testimonios de jubilados que sufrieron el desborde de los bancos". Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ González, Enric (3 April 2020). "Miles de jubilados se agolpan ante los bancos argentinos y se exponen a un contagio masivo". El Pais (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Coronavirus en Argentina: Por el caos en el pago a jubilados, la oposición pide que Alberto Fernández "separe" a los responsables". Clarin (in Spanish). Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ^ "Por la cuarentena, la actividad se derrumbó casi 10% en marzo según Ferreres". Ámbito Financiero (in Spanish). 24 April 2020. Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- ^ "El déficit fiscal primario trepó 857% en marzo por paquete "anticoronavirus" y caída en la actividad". Ámbito Financiero (in Spanish). 20 April 2020.

- ^ Maximiliano Fernandez (2 October 2020). "Estiman que al menos 1.5 millones de alumnos abandonarán la escuela después de la cuarentena" [It is estimated that 1.5 millions of students will drop school after the quarantine] (in Spanish). Infobae. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- ^ "Por qué Alberto Fernández no debería saludar con un abrazo". Chequeado (in Spanish).

- ^ ""Son verdaderas las fotos de Alberto Fernández sin barbijo y sin distanciamiento social". Chequeado (in Spanish).

- ^ "Una foto "borrada" de Alberto, Moyano y Fabiola sin barbijo ni distancia generó revuelo". Perfil.com (in Spanish).

- ^ "Coronavirus. "Seguimos hablando de cuarentena sin que en la Argentina existan cuarentenas" y otras frases de Alberto Fernández". La Nación (in Spanish).

- ^ "Alberto Fernandez: "Estuve en la calle manejando y vi que la gente en CABA sale y camina"". Infobae (in Spanish).

- ^ Jastreblansky, Maia (6 November 2020). "Alberto Fernández, Rodríguez Larreta y Kicillof confirmaron que el AMBA deja atrás la fase de "aislamiento"". La Nación (in Spanish).

- ^ "El AMBA pasa a una etapa de distanciamiento social hasta el 29 de noviembre". Ámbito Financiero (in Spanish). 6 November 2020.

- ^ "Argentina's president sits for Russian Covid jab". France 24. 21 January 2021.

- ^ Centenera, Mar (21 January 2021). "Alberto Fernández, primer presidente de América Latina en vacunarse contra la covid-19". El País (in Spanish).

- ^ "Argentina's health minister forced to resign amid COVID vaccine scandal after his ineptitude as a health minister". Euro News. 19 February 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- ^ "Coronavirus (COVID-19) Vaccinations - Statistics and Research - Our World in Data". Our World in Data.

- ^ "Argentine health minister resigns amid vaccine scandal". AP NEWS. 19 February 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ "Argentine leader Alberto Fernandez says tests positive for coronavirus". Reuters. 2 April 2021.

- ^ Camarano, Cecilia (22 March 2021). "Con un llamado a mantener la unidad, Alberto asumió la presidencia del PJ". Ámbito Financiero (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández asume la presidencia del Consejo del Partido Justicialista". Télam (in Spanish). 22 March 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Fontevecchia, Agustino (7 December 2019). "Alberto, Cristina and a distaste for institutions". Buenos Aires Times.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Alberto Fernández en Twitter: Respuestas feroces y mensajes desbocados de un tuitero que no se queda en el molde" [Alberto Fernández on Twitter: Fierce responses and uncontrolled messages from a tweeter who does not hold back]. Diario Popular (in Spanish).

- ^ "El video que expone lo peor de Alberto: sus agresiones "épicas" son virales" [The video that exposes Alberto's worst: his "epic" attacks are viral]. infotechnology.com (in Spanish).

- ^ @alferdez (19 March 2019). "Que pedazo de pelotudo resultaste. Pasaste de hacerme reír a tener pena por tu imbecilidad. Solo agradece que mi paciencia es infinita. Y rogá que tus imbéciles prepoteadas un día no se crucen con alguien sanguíneo. Seguí tu vida. Pelotudo."" [What an asshole you turned out to be. You went from making me laugh to being sorry for your stupidity. Just be thankful that my patience is infinite. And pray that one day your prepotent idiocies don't cross paths with someone with blood. Go on with your life. Asshole."] (Tweet) (in Spanish) – via Twitter.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Los insultos de Alberto Fernández a los usuarios en las redes sociales" [Alberto Fernandez's insults to social media users]. La Nación (in Spanish). 20 May 2019.

- ^ @alferdez (6 April 2019). "Pajero y pelotudo... lo tuyo no tiene cura. Y no te insulto. Te describo" [Wanker and asshole... your thing has no cure. And I don't insult you. I describe you.] (Tweet) (in Spanish) – via Twitter.

- ^ @alferdez (26 March 2019). "Andamos muy bien, pedazo de hijo de puta" [We're doing fine, you son of a bitch] (Tweet) (in Spanish) – via Twitter.

- ^ "El año de Alberto en Twitter: insultos, gifs graciosos y guiños para la unidad anti Macri" [A year of Alberto on Twitter: swearing, funny gifs and winks towards an anti-Macri ensemble]. A24 (in Spanish). 8 November 2019.

- ^ @alferdez (11 December 2017). "Nena, no es algo que me inquiete lo que vos creas. Mejor aprende a cocinar. Tal vez así logres hacer algo bien. Pensar no es tu fuerte. Está visto" [Girl, what you think doesn't worry me. You better learn how to cook. Maybe then you can do something right. Thinking is not your strong suit. It's seen.] (Tweet) (in Spanish) – via Twitter.

- ^ ""Mejor aprende a cocinar": Usuarios reviven polémicos tuits del nuevo presidente de Argentina" ["You better learn how to cook": Users revive new Argentine president's polemic tweets]. Radio Programas del Perú (in Spanish). 28 October 2019.

- ^ "El tenso cruce entre Alberto Fernández y Cristina Pérez durante una entrevista" [The tense crossing between Alberto Fernández and Cristina Pérez during an interview]. Infobae (in Spanish).

- ^ de 2020, 1 de Enero. "Alberto Fernández, en el documental de Netflix sobre la muerte del fiscal Nisman: "Hasta el día de hoy, dudo que se haya suicidado"". infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ "Giro. Alberto Fernández dijo que ahora cree que la muerte de Nisman "fue un suicidio"". www.lanacion.com.ar (in Spanish). 31 December 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2021.

- ^ "Argentinian president accused of covering up details about the country's worst terrorist attack". the Guardian. 14 January 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ "Los 4 misterios sobre la muerte del fiscal argentino Alberto Nisman que examina la serie de Netflix". BBC News Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ "Uproar after Argentina president says 'Brazilians came from the jungle'". The Guardian. Reuters. 9 June 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández le envió una carta al INADI con su posición sobre la población argentina y latinoamericana". Página/12 (in Spanish). 11 June 2021. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ Portes, Ignacio (26 August 2021). "Argentina's president tries to contain fallout from lockdown party photos". Financial Times.

- ^ "La fiscalía pidió medidas y avanza la causa por las visitas a la quinta de Olivos durante la cuarentena". La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ Mercado, Silvia (2 April 2020). "Alberto Fernández cumple 61 años: 61 fotos de su vida". Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ Gallardo, Agustín (15 December 2019). "Marcela Luchetti, la primera mujer de Alberto Fernández y madre de Estanislao". Perfil (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ "Dyhzy cambió su nombre a Tani Fernández Luchetti y ya tiene el DNI no binario: "Estoy muy feliz"". TN (in Spanish). 12 August 2021. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Leighton-Dore, Samuel (7 November 2019). "Argentina's next president says he is 'proud' of his drag queen son". SBS. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ Sánchez Granel, Guadalupe (10 December 2019). "Quién es el hijo de Alberto Fernández". El Cronista (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ Anguita, Eduardo; Cecchini, Daniel (16 May 2020). "Argentinos Juniors, el club que enloquece a Alberto Fernández: anarquistas, cracks y la oscura presencia de un represor". Infobae (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ "Dylan, el Collie "nacional y popular" de Alberto Fernández que es furor en las redes sociales". Infobae (in Spanish). 11 August 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ "Dylan o Perón, una entrevista con Alberto Fernández". Presentarse (in Spanish). 26 July 2016. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández presentó a su nuevo perro Prócer, el hijo de Dylan". Clarín (in Spanish). 20 November 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ "Alberto Fernández presentó en las redes sociales a la nueva hija de su perro Dylan". Infobae (in Spanish). 16 June 2020. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alberto Ángel Fernández. |

- Website of Alberto Fernández (in Spanish)

- Biography by CIDOB (in Spanish)

- 1959 births

- Living people

- Action for the Republic politicians

- Argentine lawyers

- Chiefs of Cabinet of Ministers of Argentina

- Members of the Buenos Aires City Legislature

- Justicialist Party politicians

- Politicians from Buenos Aires

- Presidents of Argentina

- University of Buenos Aires alumni

- University of Buenos Aires faculty