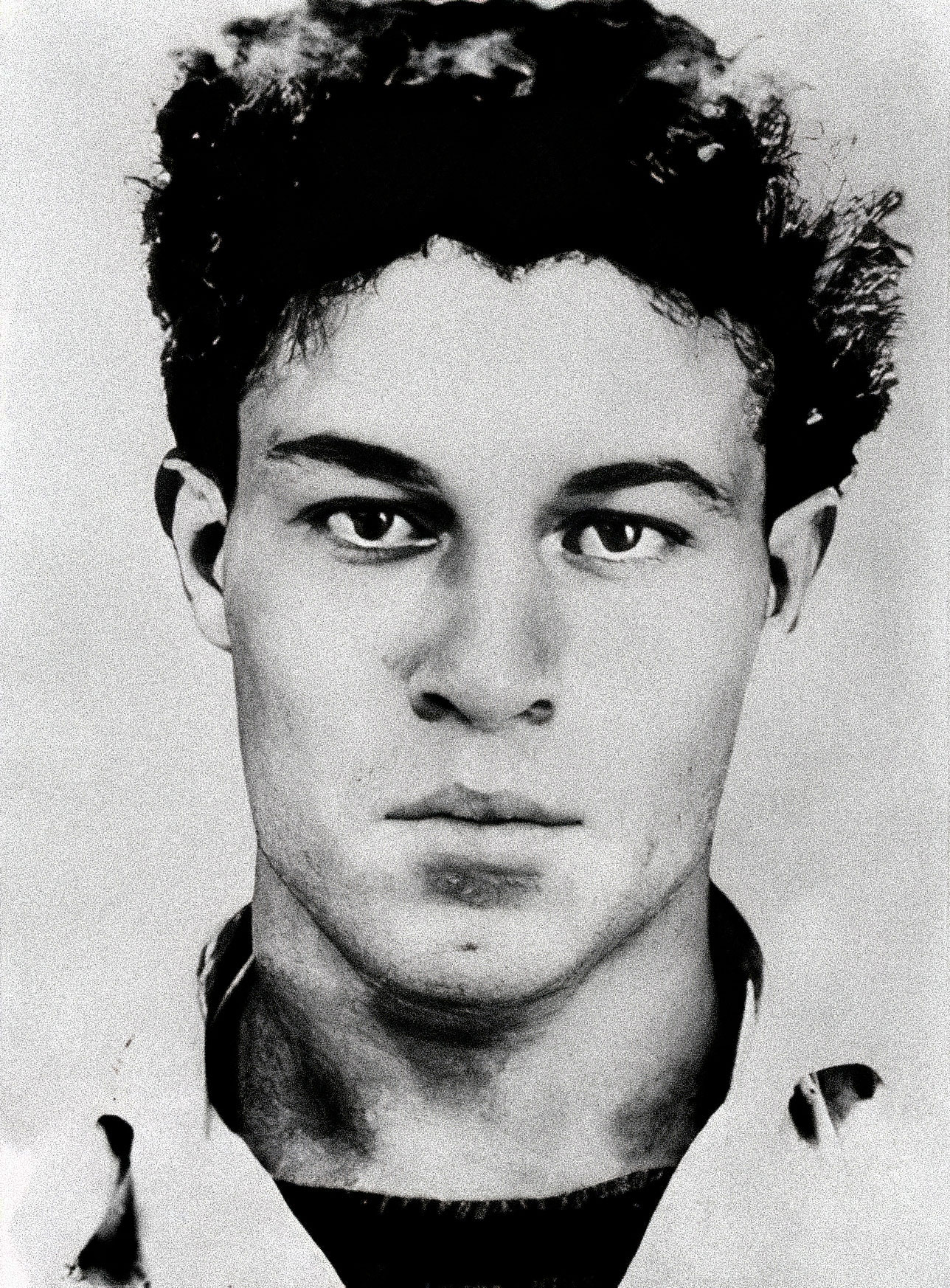

Ali La Pointe

This article includes a list of general references, but it remains largely unverified because it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (February 2011) |

show This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (February 2014) Click [show] for important translation instructions. |

Ali Ammar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 14 May 1930 |

| Died | 8 October 1957 (aged 27) |

| Other names | Ali la Pointe |

| Occupation | Freedom Fighter |

| Organization | Armée de libération nationale (ALN) |

| Known for | Battle of Algiers |

| Movement | Front de libération nationale (FLN) |

Ali Ammar (Arabic: علي عمار; 14 May 1930 – 8 October 1957), better known by his nickname Ali la Pointe, was an Algerian revolutionary fighter and guerrilla leader of the National Liberation Front who fought for Algerian independence against the French colonial regime, during the Battle of Algiers.

Ali lived a life of petty crime and was serving a two-year prison sentence when war broke out in Algeria in 1954. Recruited in the notorious Barberousse prison by FLN militants, he became one of the FLN's most trusted and loyal lieutenants in Algiers. On 28 December 1956, he was suspected of killing the Mayor of Boufarik, Amédée Froger.

In 1957 French paratroopers led by Colonel Yves Godard systematically isolated and eliminated the FLN leadership in Algiers. Godard's counter-terrorism methods included interrogation with torture. In June, la Pointe led teams in setting explosives in street lights near public transportation stops and bombing a dance club that killed 17.[1]

Saadi Yacef ordered the leadership to hide in separate addresses within the Casbah. After Yacef's capture, la Pointe and three companions, Hassiba Ben Bouali, Mahmoud "Hamid" Bouhamidi and 'Petit Omar', held out in hiding until 8 October. Tracked down by paras acting on a tip-off from an informer, Ali La Pointe was given the chance to surrender but refused, whereupon he, his companions, and the house in which he was hiding were bombed by French paratroopers. In all, 20 Algerians were killed in the blast.[2]

Biography[]

Ali Ammar was born on 14 May 1930 in Miliana, Algeria to a poor family.[3] The family's financial situation did not allow him to attend school.[4] His nickname "La Pointe" comes from the Point district in Miliana. While being imprisoned for the first time at the age of thirteen, he learned masonry.[5] In 1945, he became known in Algeria for playing tchi-tchi, a type of gambling game scam, then as a pimp and acquired a sort of prestige.[6][7] He was convicted for theft of military effects in 1943, rape in 1950, international assault and violence to an officer in 1952, and attempted homicide in 1953 and 1954.

In 1954, when the Algerian War broke out, he escaped from the Barberousse prison (Prison de Barberousse) where he was serving a two-year sentence for attempted murder. FLN, Front de libération nationale (National Liberation Front), militants explained to him that Algiers was a victim of colonialism and recruited him to their cause.[6] He later escaped again after being transferred to a prison in Damiette.[8] He returned to Algeria and made contact a few months later with Yacef Saadi.

Activity within the FLN[]

In late 1955,[9] Ali la Pointe was introduced to Yacef Saâdi, who was the deputy of Larbi Ben M'hidi, the head of the FLN for Algiers (aka Zone autonome d'Alger (autonomous zone of Algiers) during the Algerian War.[10] Yacef Saâdi "decided to test him", trusting him with the execution of a snitch on the evening of their meeting.[9][11] Recruited, according to Marie-Monique Robin for his "formidable qualities as a killer",[10] he became, according to Christopher Cradock and M.L.R. Smith, "the chief assassin" for FLN.[12] He was notably responsible for what was referred to as a "line up of the Casbah underworld with the nationalist terrorist movement" from an article by The New York Times.[13] After some figures of the local underworld suspected of being informants were executed, such as Rafai Abdelkader, Said Bud Abbot and Hocine Bourtachi,[9][11][14][15] he "sowed terror" in the casbah, according to Marie-Monique Robin by applying "revolutionary instructions, such as not allowing drinking alcohol or smoking".[10]

On 30 September 1956, two bombs exploded in two public places in Algiers, the Milk Bar and the Cafétaria, killing four and wounding fifty-two. They were planted by Zohra Drif and respectively, while a third bomb, planted by Djamila Bouhired at the Air France terminal, did not explode.[16] These events mark the beginning of the “Battle of Algiers”.[17] These three women are, with , who will plant a bomb on 26 January 1957 at the Coq Hardi brewery, part of the “bombs network” headed by Yacef Saâdi, assisted by Ali la Pointe.[18]

Legacy[]

He was portrayed by Brahim Haggiag in the film The Battle of Algiers.

References[]

- ^ Randall Law Terrorism: A History section "French Success in the Battle of Algiers and Beyond" John Wiley & Sons 2013 ISBN 978-0745640389

- ^ Universite Hassiba Ben Bouali (in French), archived from the original on 20 February 2008, retrieved 2 February 2011

- ^ Karim 0. (12 October 2011). "L'hommage à "Ali La Pointe"". Le Soir d'Algérie. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Horne, Alistair (9 August 2012). A Savage War of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962. Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4472-3343-5.

- ^ Taraud, Christelle (1 October 2008). "Les yaouleds : entre marginalisation sociale et sédition politique. Retour sur une catégorie hybride de la casbah d'Alger dans les années 1930-1960". Revue d'histoire de l'enfance " irrégulière ". Le Temps de l'histoire (in French) (Numéro 10): 59–74. doi:10.4000/rhei.2917. ISSN 1287-2431.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Massu, Jacques (1971). La vraie bataille d'Alger (in French). Plon. p. 291.

- ^ Yves, Courrière. "La bataille d'Alger". FranceArchives. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Crozier, Brian (1960). The Rebels: A Study of Post-War Insurrections. Beacon Press. p. 172.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Delmas, Jean (21 March 2007). La bataille d'Alger (in French). Larousse. ISBN 978-2-03-585477-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Robin, Marie-Monique (19 March 2015). Escadrons de la mort, l'école française (in French). La Découverte. p. 94. ISBN 978-2-7071-8668-3.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ali-la-Pointe. Souvenirs de la Bataille d'Alger 1956". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Cradock, Christopher; Smith, M. L. R. (1 October 2007). ""No Fixed Values": A Reinterpretation of the Influence of the Theory of Guerre Révolutionnaire and the Battle of Algiers, 1956–1957". Journal of Cold War Studies. 9 (4): 68–105. doi:10.1162/jcws.2007.9.4.68. ISSN 1520-3972. S2CID 57558312.

- ^ Brady, «, Thomas F. (13 October 1957). "French Step Up Algeria Fighting: Army Indicates a Recent Increase in Surrendering by Nationalist Rebels Three Actions During Day Casualties Are Listed". The New York Times.

Ali la Pointe [...] had lined up the Casbah underworld with the nationalist terrorist movement.

- ^ Bromberger, Serge (1958). Les rebelles algériens (in French). Plon. p. 147.

- ^ Duchemin, Jacques C. (2006). Histoire du FLN (in French). Éditions Mimouni. p. 215.

- ^ Hitchcock, William I. (26 November 2008). The Struggle for Europe: The Turbulent History of a Divided Continent 1945 to the Present. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-307-49140-4.

- ^ Robin, Marie-Monique (19 March 2015). Escadrons de la mort, l'école française (in French). La Découverte. p. 114. ISBN 978-2-7071-8668-3.

- ^ Naylor, Phillip C. (7 May 2015). Historical Dictionary of Algeria. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8108-7919-5.

- 1930 births

- 1957 deaths

- Members of the National Liberation Front (Algeria)

- People of the Algerian War

- Algerian guerrillas killed in action

- Deaths by explosive device

- People from Miliana

- Algerian revolutionaries