Alice's Restaurant (film)

| Alice's Restaurant | |

|---|---|

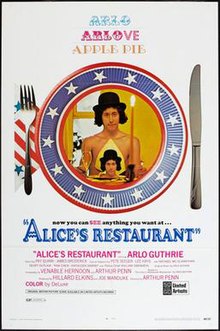

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Arthur Penn |

| Screenplay by | Venable Herndon Arthur Penn |

| Produced by | Hillard Elkins Joseph Manduke |

| Starring | Arlo Guthrie Pat Quinn William Obanhein James Broderick Pete Seeger Lee Hays |

| Cinematography | Michael Nebbia |

| Edited by | Dede Allen |

| Music by | Arlo Guthrie Garry Sherman |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 111 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $6,100,000 (North American theatrical rentals)[1][2] |

Alice's Restaurant is a 1969 American comedy film directed by Arthur Penn. It is an adaptation of the 1967 folk song "Alice's Restaurant Massacree", originally written and sung by Arlo Guthrie. The film stars Guthrie as himself, with Pat Quinn as Alice Brock and James Broderick as Ray Brock. Penn, who resided in the story's setting of Stockbridge, Massachusetts, co-wrote the screenplay in 1967 with Venable Herndon after hearing the song, shortly after directing Bonnie & Clyde.[3]

Alice's Restaurant was released on August 19, 1969, a few days after Guthrie appeared at the Woodstock Festival. A soundtrack album for the film was also released by United Artists Records. The soundtrack includes a studio version of the title song, which was originally divided into two parts (one for each album side); a 1998 CD reissue on the Rykodisc label presents this version of the song in full, and adds several bonus tracks to the original LP.

Plot[]

In 1965, Arlo Guthrie (as himself) has attempted to avoid the draft by attending college in Montana. His long hair and unorthodox approach to study gets him in trouble with local police as well as residents. He quits school, and subsequently hitchhikes back East. He first visits his father Woody Guthrie (Joseph Boley) in the hospital.

Arlo ultimately returns to his friends Ray (James Broderick) and Alice Brock (Pat Quinn) at their home, a deconsecrated church in Great Barrington, Massachusetts where they welcome friends and like-minded bohemian types to "crash". Among these are Arlo's school friend Roger (Geoff Outlaw) and artist Shelly (Michael McClanathan), an ex-heroin addict who is in a motorcycle racing club. Alice is starting up a restaurant in nearby Stockbridge. Frustrated with Ray's lackadaisical attitude, she has an affair with Shelly, and ultimately leaves for New York to visit Arlo and Roger. Ray comes to take her home, saying he has invited a "few" friends for Thanksgiving.

The central point of the film is the story told in the song: After Thanksgiving dinner, Arlo and his friends decide to do Alice and Ray a favor by taking several months worth of garbage from their house to the town dump. After loading up a red VW microbus with the garbage, and "shovels, and rakes and other implements of destruction", they head for the dump. Finding the dump closed for the holiday, they drive around and discover a pile of garbage that someone else had placed at the bottom of a short cliff. At that point, as mentioned in the song, "... we decided that one big pile is better than two little piles, and rather than bring that one up we decided to throw ours down."

The next morning they receive a phone call from "Officer Obie" (Police Chief William Obanhein as himself), who asks them about the garbage. After admitting to littering, they agree to pick up the garbage and to meet him at the police officers' station. Loading up the red VW microbus, they head to the police station where they are immediately arrested.

As the song puts it, they are then driven to the quote scene of the crime unquote where the police are engaged in a hugely elaborate investigation. At the trial, Officer Obie is anxiously awaiting the chance to show the judge the 27 8x10 color glossy photos of the crime but the judge (James Hannon as himself) happens to be blind, using a seeing eye dog, and simply levies a $25 fine, orders them to pick up the garbage and then sets them free. The garbage is eventually taken to New York and placed on a barge. Meanwhile, Arlo has fallen in love with a beautiful Asian girl, Mari-chan (Tina Chen).

Later in the movie, Arlo is called up for the draft, in a surreal depiction of the bureaucracy at the New York City military induction center on Whitehall Street. He attempts to make himself unfit for induction by acting like a homicidal maniac in front of the psychiatrist, but fails (the incident actually gets him praise). Because of Guthrie's criminal record for littering, he is first sent to the Group W bench (where convicts wait), then outright rejected as unfit for military service, not because of the littering incident, but because he makes a remark about the dubiousness of considering littering to be a problem when selecting candidates for armed conflict, making the officials suspicious of "his kind" and them to send his personal records to Washington, DC.

Upon returning to the church, Arlo finds Ray and members of the motorcycle club showing home movies of a recent race. Shelly enters, obviously high, and Ray beats him until he reveals his stash of heroin, concealed in some art he has been working on. Shelly roars off into the night on his motorcycle to his death; the next day, Woody dies. Ray and Alice have a hippie-style wedding in the church, and a drunken Ray proposes to sell the church and start a country commune instead, revealing that he blames himself for Shelly's death. The film ends with Alice standing alone in her bedraggled wedding gown on the church steps.

Cast[]

- Arlo Guthrie as himself

- Pat Quinn as Alice Brock

- James Broderick as Ray Brock

- Pete Seeger as himself

- Lee Hays as himself – reverend at evangelical meeting

- Michael McClanathan as Shelly

- Geoff Outlaw as Roger Crowther

- Tina Chen as Mari-chan

- Kathleen Dabney as Karin

- William Obanhein as himself – Officer Obie

- James Hannon as himself – the blind judge

- Seth Allen as Evangelist

- Monroe Arnold as Bluegrass

- Joseph Boley as Woody Guthrie

- Vinnette Carroll as Draft Clerk

- Sylvia Davis as Marjorie Guthrie

- Simm Landres as Private Jacob / Jake

- Eulalie Noble as Ruth

- Louis Beachner as Dean

- MacIntyre Dixon as First Deconsecration Minister

- Arthur Pierce Middleton as Second Deconsecration Minister

- Donald Marye as Funeral Director

- Shelley Plimpton as Reenie

- M. Emmet Walsh as Group W Sergeant

Cameos and special appearances[]

The real Alice Brock makes a number of cameo appearances in the film. In the scene where Ray and friends are installing insulation, she is wearing a brown turtleneck top and has her hair pulled into a ponytail. In the Thanksgiving dinner scene, she is wearing a bright pink blouse. In the wedding scene, she is wearing a Western-style dress. She declined an offer to portray herself in the film.[4]

Stockbridge police chief William Obanhein ("Officer Obie") plays himself in the film, explaining to Newsweek magazine that making himself look like a fool was preferable to having somebody else make him look like a fool.[5] Judge James E. Hannon, who presided over the littering trial, also appears as himself in the film.[6] Many of Guthrie's real-life associates in Stockbridge made appearances as extras, and Penn, who himself had a home in Stockbridge,[3] spent time living among them in an effort to grasp their lifestyle.[7] Guthrie and all of the extras were housed at the same hotel during filming of scenes outside Stockbridge, but Guthrie received star treatment; a limousine was provided for Guthrie each morning while the others had to find their own transportation for filming. This strained the relations between Guthrie and his friends for many years.[7] Much of the film was recorded in Stockbridge.[3]

The film also features the first credited film appearance of character actor M. Emmet Walsh, playing the Group W sergeant. (Walsh had previously appeared as an uncredited extra in Midnight Cowboy, released three months prior.) The film also features cameo appearances by American folksingers/songwriters Lee Hays (playing a reverend at an evangelical meeting) and Pete Seeger (playing himself).[citation needed]

Differences from real life[]

The original song "Alice's Restaurant Massacree" that formed the basis for the film's central plotline was, for the most part, a true story. However, other than this and the hippie wedding at the end of the film, most of the other events and characters in the film were fictional creations of the screenplay's writers. According to Guthrie on the DVD's audio commentary, the film used the names of real people but took numerous liberties with actual events. Richard Robbins, Guthrie's co-defendant in real-life, was replaced by the fictional Roger Crowther for the film (in the song, he remained anonymous); he later described almost all the additions to the story as "all fiction" and "complete bull."[7] The subplots involving the Shelly character were completely fictional and not based on any real people or incidents in Guthrie's life;[8] his character's motorcycle club was loosely based on the Trinity Motorcycle Club (or, by a conflicting account, the Triangle Motorcycle Club), a real-life group of motorcyclists that associated with the Brocks and were alluded to in another Guthrie song, the "Motorcycle Song".[9] The film also has Guthrie being forced to leave a Montana town after "creating a disturbance" – i.e., several town residents object to Guthrie's long hair and gang up to throw him through a plate glass window. This never happened, and Guthrie expresses regret that Montana got a "bad rap" in the film. In reality, during the time of the littering incident and trial, Guthrie was still enrolled in a Montana college, and was only in Stockbridge for the long Thanksgiving weekend (he would drop out of college at the end of the semester).[6]

Alice Brock has spoken very negatively of the film's portrayal of her.[10] She stated in a 2014 interview "That wasn't me. That was someone else's idea of me."[9] Brock took particular offense at the film implying that she had slept with Guthrie (among others) and noted that she had never associated with heroin users.[8] She also noted that the film in particular[4] had brought a large amount of unwanted publicity: "It just really impinged on your privacy. It's just amazing how brazen people can be when you're a supposed public figure (...) We sold the church at that point."[9]

Reception[]

The film has a 63% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 19 reviews, with a weighted average of 6.19/10.[11] In 2009, Politics Daily wrote that, "calling the 1969 film a comedy misses its noir backbeat of betrayed romanticism, and thinking of it as a madcap autobiography misses its politics. This is a movie driven by the military draft and the Vietnam War".[12]

Upon its initial release, Newsweek called the film "the best of a number of remarkable new films which seem to question many of the traditional assumptions of establishment America."[13]

When interviewed in 1971, the film's director, Arthur Penn, said of the film: "What I tried to deal with is the US's silence and how we can best respond to that silence. ... I wanted to show that the US is a country paralyzed by fear, that people were afraid of losing all they hold dear to them. It's the new generation that's trying to save everything".[14]

In being offered the opinion that violence is not so important in the film, Penn replied: "Alice's Restaurant is a film of potential transition because the characters know, in some way, what they are looking for. ... It's important to remember that the characters in Alice's Restaurant are middle-class whites. They aren't poor or hungry or working class. They are not in the same boat as African Americans. But they're not militants either. In this respect the church dwellers are not particularly threatening. They find it easy to live there, even if most people can't afford such a luxury. From this point of view, this film depicts a very specific social class. It's a bourgeois film".[15]

The final scene is not of a loving couple seeing off their guests, but of Alice standing alone looking into the distance, watching the guests leave, as if knowing that her future is in fact bleak with Ray.[16] Coincidentally, the real Alice and Ray finalized their divorce on the same day the wedding scene was filmed.[7] Arthur Penn has said that the final scene was intended as comment on the inevitable passing of the counterculture dream: "In fact, that last image of Alice on the church steps is intended to freeze time, to say that this paradise doesn't exist any more, it can only endure in memory".[17] Gene Siskel of the Chicago Tribune listed Alice's Restaurant as third best film of 1969.[18]

The film grossed $6,300,000[2] in the United States, making it the 23rd highest-grossing film of 1969.

Awards[]

- Nominated for Academy Award for Best Director (1969) – Arthur Penn[19]

- Nominated for Writers Guild of America Award for Best Drama Written Directly for the Screen (1970) – Venable Herndon, Arthur Penn

- Third Place – Laurel Awards – Golden Laurel for Comedy (1970)

- Nominated for British Academy of Film and Television Arts Awards – Anthony Asquith Award for Film Music (1971) – Arlo Guthrie

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "All-time Film Rental Champs", Variety, 7 January 1976 p 46

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Box Office Information for Alice's Restaurant". The Numbers. Retrieved February 26, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Cummings, Paula (November 21, 2017). Interview: Arlo Guthrie Carries On Thanksgiving Traditions And Fulfills Family Legacy. NYS Music. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Shea, Andrea (Nov 26, 2017). "Arlo Guthrie's 'Alice's Restaurant' Is A Thanksgiving Tradition. But This Year The Real Alice Needs Help". The ARTery. Retrieved Dec 7, 2020.

- ^ Zimmerman, Paul D. (September 29, 1969). "Alice's Restaurant's Children." Newsweek, page 103.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Doyle, Patrick (November 26, 2014). Arlo Guthrie looks back on 50 years of Alice's Restaurant Archived 2017-09-09 at the Wayback Machine. Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Arlo Guthrie's Alice is alive, glad to be here. The Wall Street Journal via the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (November 22, 2006). Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brown, Jane Roy (February 24, 2008). After Alice's restaurants. The Boston Globe. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Giuliano, Charles (March 27, 2014). Alice's Restaurant Returns to the Berkshires. Berkshire Fine Arts. Retrieved October 24, 2015.

- ^ "Alice quits restaurant business". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. June 21, 1970. p. 9B.

- ^ "Alice's Restaurant (1969)".

- ^ James Grady, "Thanksgiving at Alice's Restaurant: The Guthries' American Dream Lives On", Politics Daily, 25.11.2009.

- ^ Zimmerman, Paul (September 29, 1969). "Alice's Restaurant's Children". Newsweek: 101–106.

- ^ Arthur Penn (2008). Arthur Penn: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-105-7.

- ^ M. Chaiken and P. Cronin (eds), Arthur Penn Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 1998, p. 65.

- ^ M. Chaiken and P. Cronin (eds), Arthur Penn Interviews. University Press of Mississippi, 1998.

- ^ Cineaste (December 1993). "Arthur Penn Interview". cineaste. XX (2). Archived from the original on 14 September 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- ^ Siskel and Ebert Top Ten Lists. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

- ^ Awards Information for Alice's Restaurant. IMDb. Retrieved April 22, 2014.

External links[]

- 1969 films

- English-language films

- 1960s comedy road movies

- American comedy road movies

- American films

- Anti-war films about the Vietnam War

- Films about music and musicians

- Films based on songs

- Films directed by Arthur Penn

- Films set in 1965

- Films set in Massachusetts

- Films set in Montana

- Films set in New York City

- Films shot in Massachusetts

- Films shot in New York City

- Hippie films

- Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War

- Stockbridge, Massachusetts

- Thanksgiving in films

- United Artists films

- 1969 comedy films

- Cultural depictions of Woody Guthrie