Allyl alcohol

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Prop-2-en-1-ol | |

| Other names | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 3DMet | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.003.156 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 1098 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| C3H6O | |

| Molar mass | 58.080 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | colorless liquid[1] |

| Odor | mustard-like[1] |

| Density | 0.854 g/ml |

| Melting point | −129 °C |

| Boiling point | 97 °C (207 °F; 370 K) |

| Miscible | |

| Vapor pressure | 17 mmHg[1] |

| Acidity (pKa) | 15.5 (H2O)[2] |

| -36.70·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | External MSDS |

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS Signal word | Danger |

GHS hazard statements

|

H225, H301, H311, H315, H319, H331, H335, H400 |

| P210, P233, P240, P241, P242, P243, P261, P264, P270, P271, P273, P280, P301+310, P302+352, P303+361+353, P304+340, P305+351+338, P311, P312, P321, P322, P330, P332+313, P337+313, P361 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) |

3

3

1 |

| Flash point | 21 °C (70 °F; 294 K) |

| 378 °C (712 °F; 651 K) | |

| Explosive limits | 2.5–18.0% |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LC50 (median concentration)

|

1000 ppm (mammal, 1 hr) 76 ppm (rat, 8 hr) 207 ppm (mouse, 2 hr) 1000 ppm (rabbit, 3.5 hr) 1000 ppm (monkey, 4 hr) 1060 ppm (rat, 1 hr) 165 ppm (rat, 4 hr) 76 ppm (rat, 8 hr)[3] |

| NIOSH (US health exposure limits): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

2 ppm[1] |

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 2 ppm (5 mg/m3) ST 4 ppm (10 mg/m3) [skin] [1] |

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

20 ppm[1] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

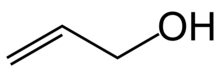

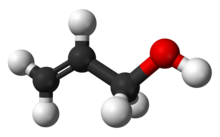

Allyl alcohol (IUPAC name: prop-2-en-1-ol) is an organic compound with the structural formula CH2=CHCH2OH. Like many alcohols, it is a water-soluble, colourless liquid. It is more toxic than typical small alcohols. Allyl alcohol is used as a raw material for the production of glycerol, but is also used as a precursor to many specialized compounds such as flame-resistant materials, drying oils, and plasticizers.[4] Allyl alcohol is the smallest representative of the allylic alcohols.

Production[]

Allyl alcohol can be obtained by many methods. It was first prepared in 1856 by Auguste Cahours and August Hofmann by hydrolysis of allyl iodide.[4] Today allyl alcohol is produced commercially by the Olin and Shell corporations through the hydrolysis of allyl chloride:

- CH2=CHCH2Cl + NaOH → CH2=CHCH2OH + NaCl

Allyl alcohol can also be made by the rearrangement of propylene oxide, a reaction that is catalyzed by potassium alum at high temperature. The advantage of this method relative to the allyl chloride route is that it does not generate salt. Also avoiding chloride-containing intermediates is the "acetoxylation" of propylene to allyl acetate:

- CH2=CHCH3 + 1/2 O2 + CH3COOH → CH2=CHCH2OCOCH3 + H2O

Hydrolysis of this acetate gives allyl alcohol. In alternative fashion, propylene can be oxidized to acrolein, which upon hydrogenation gives the alcohol.

Other methods[]

In principle, allyl alcohol can be obtained by dehydrogenation of propanol. In the laboratory, it has been prepared by the reaction of glycerol with oxalic or formic acids.[5][6] Allyl alcohols in general can be prepared by allylic oxidation of allyl compounds by selenium dioxide.

Applications[]

Allyl alcohol is converted mainly to glycidol, which is a chemical intermediate in the synthesis of glycerol, glycidyl ethers, esters, and amines. Also, a variety of polymerizable esters are prepared from allyl alcohol, e.g. diallyl phthalate.[4]

Safety[]

Allyl alcohol is more toxic than related alcohols. Its threshold limit value (TLV) is 2 ppm. It is a lachrymator.[4]

It is classified as an extremely hazardous substance in the United States as defined in Section 302 of the U.S. Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act (42 U.S.C. 11002), and is subject to strict reporting requirements by facilities which produce, store, or use it in significant quantities.[7]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0017". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Haynes, William M., ed. (2016). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (97th ed.). CRC Press. p. 5–88. ISBN 978-1498754286.

- ^ "Allyl alcohol". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Ludger Krähling; Jürgen Krey; Gerald Jakobson; Johann Grolig; Leopold Miksche (2002). "Allyl Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a01_425.

- ^ Oliver Kamm & C. S. Marvel (1941). "Allyl alcohol". Organic Syntheses.; Collective Volume, 1, p. 42

- ^ Cohen, Julius (1900). Practical Organic Chemistry (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan and Co., Limited. p. 96.

Practical Organic Chemistry Cohen Julius.

- ^ "40 C.F.R.: Appendix A to Part 355—The List of Extremely Hazardous Substances and Their Threshold Planning Quantities" (PDF) (July 1, 2008 ed.). Government Printing Office. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 25, 2012. Retrieved October 29, 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)

External links[]

- International Chemical Safety Card 0095

- NIOSH Pocket Guide to Chemical Hazards. "#0017". National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- Institut national de recherche et de sécurité (2004). "Alcool allylique." Fiche toxicologique n° 156. Paris:INRS. (in French)

- State of Michigan public information on allyl alcohol

- Occupational exposure guidelines

- Primary alcohols

- Allyl compounds

- Hepatotoxins