American Dream

The American Dream is a national ethos of the United States, the set of ideals (democracy, rights, liberty, opportunity and equality) in which freedom includes the opportunity for prosperity and success, as well as an upward social mobility for the family and children, achieved through hard work in a society with few barriers. In the definition of the American Dream by James Truslow Adams in 1931, "life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement" regardless of social class or circumstances of birth.[1]

The American Dream is rooted in the Declaration of Independence, which proclaims that "all men are created equal" with the right to "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness."[2] Also, the U.S. Constitution promotes similar freedom, in the Preamble: to "secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity".

The American Dream has been questioned by researchers and political spokespeople, arguing that it is a misplaced belief that contradicts reality in the present-day United States.

History

The meaning of the "American Dream" has changed over the course of history, and includes both personal components (such as home ownership and upward mobility) and a global vision. Historically the Dream originated in the mystique regarding frontier life. As John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore, the colonial Governor of Virginia, noted in 1774, the Americans "for ever imagine the Lands further off are still better than those upon which they are already settled". He added that, "if they attained Paradise, they would move on if they heard of a better place farther west".[3]

19th century

In the 19th century, many well-educated Germans fled the failed 1848 revolution. They welcomed the political freedoms in the New World, and the lack of a hierarchical or aristocratic society that determined the ceiling for individual aspirations. One of them explained:

The German emigrant comes into a country free from the despotism, privileged orders and monopolies, intolerable taxes, and constraints in matters of belief and conscience. Everyone can travel and settle wherever he pleases. No passport is demanded, no police mingles in his affairs or hinders his movements ... Fidelity and merit are the only sources of honor here. The rich stand on the same footing as the poor; the scholar is not a mug above the most humble mechanics; no German ought to be ashamed to pursue any occupation ... [In America] wealth and possession of real estate confer not the least political right on its owner above what the poorest citizen has. Nor are there nobility, privileged orders, or standing armies to weaken the physical and moral power of the people, nor are there swarms of public functionaries to devour in idleness credit for. Above all, there are no princes and corrupt courts representing the so-called divine 'right of birth.' In such a country the talents, energy and perseverance of a person ... have far greater opportunity to display than in monarchies.[4]

The discovery of gold in California in 1849 brought in a hundred thousand men looking for their fortune overnight—and a few did find it. Thus was born the California Dream of instant success. Historian H. W. Brands noted that in the years after the Gold Rush, the California Dream spread across the nation:

The old American Dream ... was the dream of the Puritans, of Benjamin Franklin's "Poor Richard"... of men and women content to accumulate their modest fortunes a little at a time, year by year by year. The new dream was the dream of instant wealth, won in a twinkling by audacity and good luck. [This] golden dream ... became a prominent part of the American psyche only after Sutter's Mill."[5]

Historian Frederick Jackson Turner in 1893 advanced the frontier thesis, under which American democracy and the American Dream were formed by the American frontier. He stressed the process—the moving frontier line—and the impact it had on pioneers going through the process. He also stressed results; especially that American democracy was the primary result, along with egalitarianism, a lack of interest in high culture, and violence. "American democracy was born of no theorist's dream; it was not carried in the Susan Constant to Virginia, nor in the Mayflower to Plymouth. It came out of the American forest, and it gained new strength each time it touched a new frontier," said Turner.[6] In the thesis, the American frontier established liberty by releasing Americans from European mindsets and eroding old, dysfunctional customs. The frontier had no need for standing armies, established churches, aristocrats or nobles, nor for landed gentry who controlled most of the land and charged heavy rents. Frontier land was free for the taking. Turner first announced his thesis in a paper entitled "The Significance of the Frontier in American History", delivered to the American Historical Association in 1893 in Chicago. He won wide acclaim among historians and intellectuals. Turner elaborated on the theme in his advanced history lectures and in a series of essays published over the next 25 years, published along with his initial paper as The Frontier in American History.[7] Turner's emphasis on the importance of the frontier in shaping American character influenced the interpretation found in thousands of scholarly histories. By the time Turner died in 1932, 60% of the leading history departments in the U.S. were teaching courses in frontier history along Turnerian lines.[8]

20th century

Freelance writer James Truslow Adams popularized the phrase "American Dream" in his 1931 book Epic of America:

But there has been also the American dream, that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for every man, with opportunity for each according to his ability or achievement. It is a difficult dream for the European upper classes to interpret adequately, and too many of us ourselves have grown weary and mistrustful of it. It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable, and be recognized by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position... The American dream, that has lured tens of millions of all nations to our shores in the past century has not been a dream of merely material plenty, though that has doubtlessly counted heavily. It has been much more than that. It has been a dream of being able to grow to fullest development as man and woman, unhampered by the barriers which had slowly been erected in the older civilizations, unrepressed by social orders which had developed for the benefit of classes rather than for the simple human being of any and every class.[citation needed]

Martin Luther King Jr., in his "Letter from a Birmingham Jail" (1963) rooted the civil rights movement in the African-American quest for the American Dream:[9]

We will win our freedom because the sacred heritage of our nation and the eternal will of God are embodied in our echoing demands ... when these disinherited children of God sat down at lunch counters they were in reality standing up for what is best in the American dream and for the most sacred values in our Judeo-Christian heritage, thereby bringing our nation back to those great wells of democracy which were dug deep by the Founding Fathers in their formulation of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

Literature

The concept of the American Dream has been used in popular discourse, and scholars have traced its use in American literature ranging from the Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin,[10] to Mark Twain's Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), Willa Cather's My Ántonia,[11] F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby (1925), Theodore Dreiser's An American Tragedy (1925) and Toni Morrison's Song of Solomon (1977).[12] Other writers who used the American Dream theme include Hunter S. Thompson, Edward Albee,[13] John Steinbeck,[14] Langston Hughes,[15] and Giannina Braschi.[16] The American Dream is also discussed in Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman as the play's protagonist, Willy, is on a quest for the American Dream.

As Huang shows, the American Dream is a recurring theme in the fiction of Asian Americans.[17][18]

American ideals

Many American authors added American ideals to their work as a theme or other reoccurring idea, to get their point across.[19] There are many ideals that appear in American literature such as, but not limited to, all people are equal, United States of America is the Land of Opportunity, independence is valued, The American Dream is attainable, and everyone can succeed with hard work and determination. John Winthrop also wrote about this term called, American exceptionalism. This ideology refers to the idea that Americans are, as a nation, elect.[20]

Literary commentary

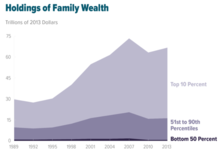

The American Dream has been credited with helping to build a cohesive American experience, but has also been blamed for inflated expectations.[22] Some commentators have noted that despite deep-seated belief in the egalitarian American Dream, the modern American wealth structure still perpetuates racial and class inequalities between generations.[23] One sociologist notes that advantage and disadvantage are not always connected to individual successes or failures, but often to prior position in a social group.[23]

Since the 1920s, numerous authors, such as Sinclair Lewis in his 1922 novel Babbitt, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, in his 1925 classic, The Great Gatsby, satirized or ridiculed materialism in the chase for the American dream. For example, Jay Gatsby's death mirrors the American Dream's demise, reflecting the pessimism of modern-day Americans.[24] The American Dream is a main theme in the book by John Steinbeck, Of Mice and Men. The two friends George and Lennie dream of their own piece of land with a ranch, so they can "live off the fatta the lan'" and just enjoy a better life. The book later shows that not everyone can achieve the American Dream, although it is possible to achieve for a few. A lot of people follow the American Dream to achieve a greater chance of becoming rich. Some posit that the ease of achieving the American Dream changes with technological advances, availability of infrastructure and information, government regulations, state of the economy, and with the evolving cultural values of American demographics.

In 1949, Arthur Miller wrote Death of a Salesman, in which the American Dream is a fruitless pursuit. Similarly, in 1971 Hunter S. Thompson depicted in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey Into the Heart of the American Dream a dark psychedelic reflection of the concept—successfully illustrated only in wasted pop-culture excess.[25]

The novel Requiem for a Dream by Hubert Selby Jr. is an exploration of the pursuit of American success as it turns delirious and lethal, told through the ensuing tailspin of its main characters. George Carlin famously wrote the joke "it's called the American dream because you have to be asleep to believe it".[26] Carlin pointed to "the big wealthy business interests that control things and make all the important decisions" as having a greater influence than an individual's choice.[26] Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Chris Hedges echos this sentiment in his 2012 book Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt:[27]

The vaunted American dream, the idea that life will get better, that progress is inevitable if we obey the rules and work hard, that material prosperity is assured, has been replaced by a hard and bitter truth. The American dream, we now know, is a lie. We will all be sacrificed. The virus of corporate abuse – the perverted belief that only corporate profit matters – has spread to outsource our jobs, cut the budgets of our schools, close our libraries, and plague our communities with foreclosures and unemployment.

The American Dream, and the sometimes dark response to it, has been a long-standing theme in American film.[28] Many counterculture films of the 1960s and 1970s ridiculed the traditional quest for the American Dream. For example, Easy Rider (1969), directed by Dennis Hopper, shows the characters making a pilgrimage in search of "the true America" in terms of the hippie movement, drug use, and communal lifestyles.[29]

Political leaders

Scholars have explored the American Dream theme in the careers of numerous political leaders, including Henry Kissinger,[30] Hillary Clinton,[31] Benjamin Franklin, and Abraham Lincoln.[32] The theme has been used for many local leaders as well, such as José Antonio Navarro, the Tejano leader (1795–1871), who served in the legislatures of Coahuila y Texas, the Republic of Texas, and the State of Texas.[33]

In 2006 U.S. Senator Barack Obama wrote a memoir, The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream. It was this interpretation of the American Dream for a young black man that helped establish his statewide and national reputations.[34][35] The exact meaning of the Dream became for at least one commentator a partisan political issue in the 2008 and 2012 elections.[36]

Political conflicts, to some degree, have been ameliorated by the shared values of all parties in the expectation that the American Dream will resolve many difficulties and conflicts.[37]

Public opinion

"A lot of Americans think the U.S. has more social mobility than other western industrialized countries. This (study using medians instead of averages that underestimate the range and show less stark distinctions between the top and bottom tiers) makes it abundantly clear that we have less. Your circumstances at birth—specifically, what your parents do for a living—are an even bigger factor in how far you get in life than we had previously realized. Generations of Americans considered the United States to be a land of opportunity. This research raises some sobering questions about that image."— Michael Hout, Professor of Sociology at New York University – 2018[38]

The ethos today implies an opportunity for Americans to achieve prosperity through hard work. According to The Dream, this includes the opportunity for one's children to grow up and receive a good education and career without artificial barriers. It is the opportunity to make individual choices without the prior restrictions that limited people according to their class, caste, religion, race, or ethnicity. Immigrants to the United States sponsored ethnic newspapers in their own language; the editors typically promoted the American Dream.[39] argues:

For many in both the working class and the middle class, upward mobility has served as the heart and soul of the American Dream, the prospect of "betterment" and to "improve one's lot" for oneself and one's children much of what this country is all about. "Work hard, save a little, send the kids to college so they can do better than you did, and retire happily to a warmer climate" has been the script we have all been handed.[40]

A key element of the American Dream is promoting opportunity for one's children, Johnson interviewing parents says, "This was one of the most salient features of the interview data: parents—regardless of background—relied heavily on the American Dream to understand the possibilities for children, especially their own children".[41] Rank et al. argue, "The hopes and optimism that Americans possess pertain not only to their own lives, but to their children's lives as well. A fundamental aspect of the American Dream has always been the expectation that the next generation should do better than the previous generation."[42]

Hanson and Zogby (2010) report on numerous public opinion polls that since the 1980s have explored the meaning of the concept for Americans, and their expectations for its future. In these polls, a majority of Americans consistently reported that for their family, the American Dream is more about spiritual happiness than material goods. Majorities state that working hard is the most important element for getting ahead. However, an increasing minority stated that hard work and determination does not guarantee success. Most Americans predict that achieving the Dream with fair means will become increasingly difficult for future generations. They are increasingly pessimistic about the opportunity for the working class to get ahead; on the other hand, they are increasingly optimistic about the opportunities available to poor people and to new immigrants. Furthermore, most support programs make special efforts to help minorities get ahead.[43]

In a 2013 poll by YouGov, 41% of responders said it is impossible for most to achieve the American Dream, while 38% said it is still possible.[45] Most Americans perceive a college education as the ticket to the American Dream.[46] Some recent observers warn that soaring student loan debt crisis and shortages of good jobs may undermine this ticket.[47] The point was illustrated in The Fallen American Dream,[48] a documentary film that details the concept of the American Dream from its historical origins to its current perception.

Research published in 2013 shows that the US provides, alongside the United Kingdom and Spain, the least economic mobility of any of 13 rich, democratic countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.[49][50] Prior research suggested that the United States shows roughly average levels of occupational upward mobility and shows lower rates of income mobility than comparable societies.[51][52] Blanden et al. report, "the idea of the US as 'the land of opportunity' persists; and clearly seems misplaced."[53] According to these studies, "by international standards, the United States has an unusually low level of intergenerational mobility: our parents' income is highly predictive of our incomes as adults. Intergenerational mobility in the United States is lower than in France, Germany, Sweden, Canada, Finland, Norway and Denmark. Research in 2006 found that among high-income countries for which comparable estimates are available, only the United Kingdom had a lower rate of mobility than the United States."[54] Economist Isabel Sawhill concluded that "this challenges the notion of America as the land of opportunity".[55][56][57] Several public figures and commentators, from David Frum to Richard G. Wilkinson, have noted that the American dream is better realized in Denmark, which is ranked as having the highest social mobility in the OECD.[58][59][60][61][62] In the U.S., 50% of a father's income position is inherited by his son. In contrast, the amount in Norway or Canada is less than 20%. Moreover, in the U.S. 8% of children raised in the bottom 20% of the income distribution are able to climb to the top 20% as adult, while the figure in Denmark is nearly double at 15%.[63] In 2015, economist Joseph Stiglitz stated, "Maybe we should be calling the American Dream the Scandinavian Dream."[64]

In the United States, home ownership is sometimes used as a proxy for achieving the promised prosperity; home ownership has been a status symbol separating the middle classes from the poor.[65]

Sometimes the Dream is identified with success in sports or how working class immigrants seek to join the American way of life.[66]

According to a 2020 American Journal of Political Science study, Americans become less likely to believe in the attainability of the American dream as income inequality increases.[67]

Writing after the 2020 general election, Chris Hedges asserted that the surrender of the liberal elite to despotism creates a power vacuum, and quoted the novelist J. G. Ballard: "The American Dream has run out of gas. The car has stopped. It no longer supplies the world with its images, its dreams, its fantasies. No more. It’s over. It supplies the world with its nightmares now."[68]

Four dreams of consumerism

Ownby (1999) identifies four American Dreams that the new consumer culture addressed. The first was the "Dream of Abundance" offering a cornucopia of material goods to all Americans, making them proud to be the richest society on earth. The second was the "Dream of a Democracy of Goods" whereby everyone had access to the same products regardless of race, gender, ethnicity, or class, thereby challenging the aristocratic norms of the rest of the world whereby only the rich or well-connected are granted access to luxury. The "Dream of Freedom of Choice" with its ever-expanding variety of good allowed people to fashion their own particular lifestyle. Finally, the "Dream of Novelty", in which ever-changing fashions, new models, and unexpected new products broadened the consumer experience in terms of purchasing skills and awareness of the market, and challenged the conservatism of traditional society and culture, and even politics. Ownby acknowledges that the dreams of the new consumer culture radiated out from the major cities, but notes that they quickly penetrated the most rural and most isolated areas, such as rural Mississippi. With the arrival of the model T after 1910, consumers in rural America were no longer locked into local general stores with their limited merchandise and high prices in comparison to shops in towns and cities. Ownby demonstrates that poor black Mississippians shared in the new consumer culture, both inside Mississippi, and it motivated the more ambitious to move to Memphis or Chicago.[69][70]

Other parts of the world

The aspirations of the "American Dream" in the broad sense of upward mobility have been systematically spread to other nations since the 1890s as American missionaries and businessmen consciously sought to spread the Dream, says Rosenberg. Looking at American business, religious missionaries, philanthropies, Hollywood, labor unions and Washington agencies, she says they saw their mission not in catering to foreign elites but instead reaching the world's masses in democratic fashion. "They linked mass production, mass marketing, and technological improvement to an enlightened democratic spirit ... In the emerging litany of the American dream what historian Daniel Boorstin later termed a "democracy of things" would disprove both Malthus's predictions of scarcity and Marx's of class conflict." It was, she says "a vision of global social progress."[71] Rosenberg calls the overseas version of the American Dream "liberal-developmentalism" and identified five critical components:

(1) belief that other nations could and should replicate America's own developmental experience; (2) faith in private free enterprise; (3) support for free or open access for trade and investment; (4) promotion of free flow of information and culture; and (5) growing acceptance of [U.S.] governmental activity to protect private enterprise and to stimulate and regulate American participation in international economic and cultural exchange.[72]

Knights and McCabe argued American management gurus have taken the lead in exporting the ideas: "By the latter half of the twentieth century they were truly global and through them the American Dream continues to be transmitted, repackaged and sold by an infantry of consultants and academics backed up by an artillery of books and videos".[73]

After World War II

In West Germany after World War II, says Reiner Pommerin, "the most intense motive was the longing for a better life, more or less identical with the American dream, which also became a German dream".[74] Cassamagnaghi argues that to women in Italy after 1945, films and magazine stories about American life offered an "American dream." New York City especially represented a sort of utopia where every sort of dream and desire could become true. Italian women saw a model for their own emancipation from second class status in their patriarchal society.[75]

Britain

The American dream regarding home ownership had little resonance before the 1980s.[76] In the 1980s, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher worked to create a similar dream, by selling public-housing units to their tenants. Her Conservative Party called for more home ownership: "HOMES OF OUR OWN: To most people ownership means first and foremost a home of their own ... We should like in time to improve on existing legislation with a realistic grants scheme to assist first-time buyers of cheaper homes."[77] Guest calls this Thatcher's approach to the American Dream.[78] Knights and McCabe argue that, "a reflection and reinforcement of the American Dream has been the emphasis on individualism as extolled by Margaret Thatcher and epitomized by the 'enterprise' culture."[79]

Russia

Since the fall of communism in the Soviet Union in 1991, the American Dream has fascinated Russians.[80] The first post-Communist leader Boris Yeltsin embraced the "American way" and teamed up with Harvard University free market economists Jeffrey Sachs and Robert Allison to give Russia economic shock therapy in the 1990s. The newly independent Russian media idealized America and endorsed shock therapy for the economy.[81] In 2008 Russian President Dmitry Medvedev lamented the fact that 77% of Russia's 142 million people live "cooped up" in apartment buildings. In 2010 his administration announced a plan for widespread home ownership: "Call it the Russian dream", said Alexander Braverman, the Director of the Federal Fund for the Promotion of Housing Construction Development. Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, worried about his nation's very low birth rate, said he hoped home ownership will inspire Russians "to have more babies".[82]

China

The Chinese Dream describes a set of ideals in the People's Republic of China. It is used by journalists, government officials and activists to describe the aspiration of individual self-improvement in Chinese society. Although the phrase has been used previously by Western journalists and scholars,[83][84] a translation of a New York Times article written by the American journalist Thomas Friedman, "China Needs Its Own Dream", has been credited with popularizing the concept in China.[84] He attributes the term to Peggy Liu and the environmental NGO JUCCCE's China Dream project,[85][86] which defines the Chinese Dream as sustainable development.[86] In 2013, China's new paramount leader Xi Jinping began promoting the phrase as a slogan, leading to its widespread use in the Chinese media.[87]

The concept of Chinese Dream is very similar to the idea of "American Dream". It stresses entrepreneurship and glorifies a generation of self-made men and women in post-reform China, such as rural immigrants who moved to the urban centers and achieve magnificent improvement in terms of their living standards, and social life. Chinese Dream can be interpreted as the collective consciousness of Chinese people during the era of social transformation and economic progress. The idea was put forward by Chinese Communist Party new General Secretary Xi Jinping on November 29, 2012. The government hoped to revitalize China, while promoting innovation and technology to boost the international prestige of China. In this light, the Chinese Dream, like American exceptionalism, is a nationalistic concept as well.

According to Ellen Brown, writing in 2019, over 90% of Chinese families own their own homes, giving the country one of the highest rates of home ownership in the world.[88]

Criticisms

Some critics believe that such attitudes make individual thought and resistance inconsiderable and lead to the production of Popular culture. Popular culture ostensibly and superficially supports the notion of individualism that is so prevalent in American culture, but it actually destroys individuality by eliminating selection and the establishment of inclusive structures. The American Dream has become a tool for institutions to impose oversight through pre-defined patterns of behavior. Legitimate institutions, including the media, government, the entertainment and education industries, are seeking to sell the American dream. Providers of cultural and economic goods engrave the message of the American Dream in the heart of society through the repeated themes of advertising, the acceptance of celebrities, and electoral contests: "This is what makes you happy." This is a kind of organized social deception and limits people's information to choose their way of life.[89]

The high crime rate in the United States stems in part from the fact that American society, by promoting the American dream metaphor, encourages people to pursue the goal of financial success; But it underestimates legitimate tools for achieving goals. In other words, legitimately accepted cultural norms are sacrificed for a purpose that is more important than life. This is a worldview error manifested in a large society.[90][91][92][93]

See also

- Achievement ideology

- Center for a New American Dream

- Empire of Liberty

- American way

- Chinese Dream

References

- ^ "Lesson Plan: The American Dream". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved October 30, 2020.

- ^ Kamp, David (April 2009). "Rethinking the American Dream". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on May 30, 2009. Retrieved June 20, 2009.

- ^ Lord Dunmore to Lord Dartmouth, December 24, 1774, quoted in John Miller, Origins of the American Revolution (1944) p. 77

- ^ F. W. Bogen, The German in America (Boston, 1851), quoted in Stephen Ozment, A Mighty Fortress: A New History of the German People (2004) pp. 170–71

- ^ H. W. Brands, The age of gold: the California Gold Rush and the new American dream (2003) p. 442.

- ^ Turner, Frederick Jackson (1920). "The Significance of the Frontier in American History". The Frontier in American History. p. 293.

- ^ Turner, The Frontier in American History (1920) chapter 1

- ^ Bogue, Allan G. (1994). "Frederick Jackson Turner Reconsidered". The History Teacher. 27 (2). p. 195. doi:10.2307/494720. JSTOR 494720.

- ^ Quoted in James T. Kloppenberg, The Virtues of Liberalism (1998). p. 147

- ^ J. A. Leo Lemay, "Franklin's Autobiography and the American Dream," in J. A. Leo Lemay and P. M. Zall, eds. Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography (Norton Critical Editions, 1986) pp. 349–360

- ^ James E. Miller, Jr., "My Antonia and the American Dream" Prairie Schooner 48, no. 2 (Summer 1974) pp. 112–123.

- ^ Harold Bloom and Blake Hobby, eds. The American Dream (2009)

- ^ Nicholas Canaday, Jr., "Albee's The American Dream and the Existential Vacuum." South Central Bulletin Vol. 26, No. 4 (Winter 1966) pp. 28–34

- ^ Hayley Haugen, ed., The American Dream in John Steinbeck's of Mice and Men (2010)

- ^ Lloyd W. Brown, "The American Dream and the Legacy of Revolution in the Poetry of Langston Hughes" Studies in Black Literature (Spring 1976) pp. 16–18.

- ^ Riofio, John (2015). "Fractured Dreams: Life and Debt in United States of Banana" (PDF). Biennial Conference on Latina/o Utopias Literatures: "Latina/o Utopias: Futures, Forms, and the Will of Literature".

Braschi's novel is a scathing critique...of over-wrought concepts of Liberty and the American Dream....(It) connects the dots between 9/11, the suppression of individual liberties, and the fragmentation of the individuals and communities in favor of a collective worship of the larger dictates of the market and the economy.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ anupama jain (2011). How to Be South Asian in America: Narratives of Ambivalence and Belonging. Temple University Press. ISBN 9781439903032. Retrieved November 27, 2018.

- ^ Guiyou Huang, The Columbia guide to Asian American literature since 1945 (2006), pp 44, 67, 85, 94.

- ^ Neumann, Henry. Teaching American Ideals through Literature. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1918. Print.

- ^ Symposium: The Role of the Judge in the Twenty-first Century. Boston: Boston U Law School, 2006. Print.

- ^ The pictures originally illustrated a cautionary tale published in 1869 in the Swedish periodical Läsning för folket, the organ of the Society for the Propagation of Useful Knowledge (Sällskapet för nyttiga kunskapers spridande). H. Arnold Barton, A Folk Divided: Homeland Swedes and Swedish Americans, 152547256425264562564562462654666 FILS DE (Uppsala, 1994) p. 71.

- ^ Greider, William. The Nation, May 6, 2009. The Future of the American Dream

- ^ Jump up to: a b Johnson, 2006, pp. 6–10. "The crucial point is not that inequalities exist, but that they are being perpetuated in recurrent patterns—they are not always the result of individual success or failure, nor are they randomly distributed throughout the population. In the contemporary United States, the structure of wealth systematically transmits race and class inequalities through generations despite deep-rooted belief otherwise."

- ^ Dalton Gross and MaryJean Gross, Understanding The Great Gatsby (1998) p. 5

- ^ Stephen E. Ambrose, Douglas Brinkley, Witness to America (1999) p. 518

- ^ Jump up to: a b Smith, Mark A. (2010) The Mobilization and Influence of Business Interests in L. Sandy Maisel, Jeffrey M. Berry (2010) The Oxford Handbook of American Political Parties and Interest Groups p. 460; see also: Video: George Carlin "It's called the American Dream because you have to be asleep to believe it." The Progressive, June 24, 2008.

- ^ Chris Hedges and Joe Sacco (2012). Days of Destruction, Days of Revolt. pp. 226–227. Nation Books. ISBN 1568586434

- ^ Gordon B. Arnold. Projecting the End of the American Dream: Hollywood's Vision of U.S. Decline. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger, 2013.

- ^ Barbara Klinger, "The Road to Dystopia: Landscaping the Nation in Easy Rider" in Steven Cohan, ed. The Road Movie Book (1997).

- ^ Jeremi Suri, "Henry Kissinger, the American Dream, and the Jewish Immigrant Experience in the Cold War," Diplomatic History, Nov 2008, Vol. 32 Issue 5, pp. 719–747

- ^ Dan Dervin, "The Dream-Life of Hillary Clinton", Journal of Psychohistory, Fall 2008, Vol. 36 Issue 2, pp. 157–162

- ^ Edward J. Blum, "Lincoln's American Dream: Clashing Political Perspectives", Journal of the Abraham Lincoln Association, Summer 2007, Vol. 28 Issue 2, pp. 90–93

- ^ David McDonald, Jose Antonio Navarro: In Search of the American Dream in Nineteenth-Century Texas (Texas State Historical Association, 2011)

- ^ Deborah F. Atwater, "Senator Barack Obama: The Rhetoric of Hope and the American Dream," Journal of Black Studies, Nov 2007, Vol. 38 Issue 2, pp. 121–129

- ^ Willie J. Harrell, "'The Reality of American Life Has Strayed From Its Myths,'" Journal of Black Studies, Sep 2010, Vol. 41 Issue 1, pp. 164–183 online

- ^ Matthias Maass, "Which Way to Take the American Dream: The U.S. Elections of 2008 and 2010 as a Struggle for Political Ownership of the American Dream," Australasian Journal of American Studies (July 2012), vol 31 pp. 25–41.

- ^ James Laxer and Robert Laxer, The Liberal Idea of Canada: Pierre Trudeau and the Question of Canada's Survival (1977) pp. 83–85

- ^ "Lack of social mobility more of an 'occupational hazard' than previously known".

- ^ Leara D. Rhodes, The Ethnic Press: Shaping the American Dream (Peter Lang Publishing; 2010)

- ^ Lawrence R. Samuel (2012). The American Dream: A Cultural History. Syracuse UP. p. 7. ISBN 9780815651871.

- ^ Heather Beth Johnson (2014). American Dream and Power Wealth. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 9781134728794.

- ^ Mark Robert Rank; et al. (2014). Chasing the American Dream: Understanding What Shapes Our Fortunes. Oxford U.P. p. 61. ISBN 9780195377910.

- ^ Sandra L. Hanson, and John Zogby, "The Polls – Trends," Public Opinion Quarterly, Sept 2010, Vol. 74 Issue 3, pp. 570–584

- ^ "Trends in Family Wealth, 1989 to 2013". Congressional Budget Office. August 18, 2016.

- ^ Henderson, Ben. "American Dream Slipping Away, But Hope Intact". YouGov. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Americans View Higher Education as Key to American Dream Public Agenda - May 2000

- ^ Donald L. Barlett; James B. Steele (2012). The Betrayal of the American Dream. PublicAffairs. pp. 125–126. ISBN 9781586489700.

- ^ The Fallen American Dream Archived June 30, 2013, at archive.today

- ^ Autor, David (May 23, 2014), "Skills, education, and the rise of earnings inequality among the "other 99 percent"", Science Magazine, 344 (6186), pp. 843–851, Bibcode:2014Sci...344..843A, doi:10.1126/science.1251868, hdl:1721.1/96768, PMID 24855259, S2CID 5622764

- ^ Corak M (2013). "Inequality from Generation to Generation: The United States in Comparison". In Rycroft RS (ed.). The Economics of Inequality, Poverty, and Discrimination in the 21st Century. ABC-CLIO. p. 111. ISBN 9780313396922.

- ^ Beller, Emily; Hout, Michael (2006). "Intergenerational Social Mobility: The United States in Comparative Perspective". The Future of Children. 16 (2): 19–36. doi:10.1353/foc.2006.0012. JSTOR 3844789. PMID 17036544. S2CID 26362679.

- ^ Miles Corak, "How to Slide Down the 'Great Gatsby Curve': Inequality, Life Chances, and Public Policy in the United States", December 2012, Center for American Progress.

- ^ Jo Blanden; Paul Gregg; Stephen Machin (April 2005). "Intergenerational Mobility in Europe and North America" (PDF). The Sutton Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 20, 2013.

- ^ CAP: Understanding Mobility in America - April 26, 2006

- ^ Economic Mobility: Is the American Dream Alive and Well? Archived May 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Economic Mobility Project - May 2007

- ^ Obstacles to social mobility weaken equal opportunities and economic growth, says OECD study, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Economics Department, February 10, 2010.

- ^ Harder for Americans to Rise From Lower Rungs | By JASON DePARLE | January 4, 2012

- ^ David Frum (October 19, 2011). The American Dream moves to Denmark. The Week. Retrieved December 12, 2014.

- ^ Wilkinson, Richard (Oct 2011). How economic inequality harms societies (transcript). TED. (Quote featured on his personal profile on the TED website). Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ Diane Roberts (January 17, 2012). Want to get ahead? Move to Denmark. The Guardian. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ Kerry Trueman (October 7, 2011). Looking for the American Dream? Try Denmark. The Huffington Post. Retrieved December 13, 2014.

- ^ Matt O'Brien (August 3, 2016). This country has figured out the only way to save the American Dream. The Washington Post. Retrieved September 18, 2016.

- ^ Rank, Mark R; Eppard, Lawrence M. "The American Dream of upward mobility is broken. Look at the numbers". The Guardian.

- ^ 'Scandinavian Dream' is true fix for America's income inequality. CNN Money. June 3, 2015.

- ^ William M. Rohe and Harry L. Watson, Chasing the American Dream: New Perspectives on Affordable Homeownership (2007)

- ^ Thomas M. Tarapacki, Chasing the American Dream: Polish Americans in Sports (1995); Steve Wilson. The Boys from Little Mexico: A Season Chasing the American Dream (2010) is a true story of immigrant boys on a high school soccer team who struggle not only in their quest to win the state championship, but also in their desire to adapt as strangers in a new land.

- ^ Wolak, Jennifer; Peterson, David A. M. (2020). "The Dynamic American Dream". American Journal of Political Science. 64 (4): 968–981. doi:10.1111/ajps.12522. ISSN 1540-5907.

- ^ Hedges, Chris (November 5, 2020). "American Requiem". Scheerpost. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Ted Ownby, American Dreams in Mississippi: Consumers, Poverty, and Culture 1830–1998 (University of North Carolina Press, 1999)

- ^ Christopher Morris, "Shopping for America in Mississippi, or How I Learn to Stop Complaining and Love the Pemberton Mall," Reviews in American History" March 2001 v.29#1 103–110

- ^ Emily S. Rosenberg, Spreading the American Dream: American Economic and Cultural Expansion 1890–1945 (1982) pp. 22–23

- ^ Rosenberg, Spreading the American Dream p. 7

- ^ David Knights and Darren McCabe, Organization and Innovation: Guru Schemes and American Dreams (2003) p 35

- ^ Reiner Pommerin (1997). The American Impact on Postwar Germany. Berghahn Books. p. 84. ISBN 9781571810953.

- ^ Cassamagnaghi, Silvia. "New York nella stampa femminile italiana del secondo dopoguerra ["New York in the Italian women's press after World War II"]". STORIA URBANA (Dec. 2005): 91–111.

- ^ Niall Ferguson, The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World (2009) p .252

- ^ See "Conservative manifesto, 1979 Archived May 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ David E. Guest, "Human Resource Management and the American Dream," Journal of Management Studies (1990) 27#4 pp. 377–97, reprinted in Michael Poole, Human Resource Management: Origins, Developments and Critical Analyses (1999) p. 159

- ^ Knights and McCabe, Organization and Innovation (2003) p. 4

- ^ Richard M. Ryan et al., "The American Dream in Russia: Extrinsic Aspirations and Well-Being in Two Cultures," Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, (Dec. 1999) vol. 25 no. 12 pp. 1509–1524, shows the Russian ideology converging toward the American one, especially among men.

- ^ Donald J. Raleigh (2011). Soviet Baby Boomers: An Oral History of Russia's Cold War Generation. Oxford U.P. p. 331. ISBN 9780199744343.

- ^ Anastasia Ustinova, "Building the New Russian Dream, One Home at a Time", Bloomberg Business Week, June 28 – July 4, 2010, pp. 7–8

- ^ Fallows, James (May 3, 2013). "Today's China Notes: Dreams, Obstacles". The Atlantic.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The role of Thomas Friedman". The Economist. May 6, 2013.

- ^ Fish, Isaac Stone (May 3, 2013). "Thomas Friedman: I only deserve partial credit for coining the 'Chinese dream'". Foreign Policy.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "China Dream". JUCCCE.

- ^ Xi Jinping and the Chinese Dream The Economist May 4, 2013, p. 11

- ^ Brown, Ellen (June 13, 2019). "The American Dream Is Alive and Well—in China". Truthdig. Retrieved June 15, 2019.

- ^ Dermo, Sendey (June 2014). "رویای آمریکایی؛ رویکردی نظری به فهم سرمایهداری مصرف گرا" [American Dream; A theoretical approach to understanding consumerist capitalism]. Sooreh Andisheh (in Persian) (76): 47–53.

- ^ Cote, Suzette (2002). "Crime and American Dream". Criminological Theories: Bridging the Past to the Future.

- ^ Sims, Barbara A. (February 1, 1997). "Crime, Punishment, and the American Dream: Toward a Marxist Integration". Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 34 (1).

- ^ Messner, Steven; Rosenfeld, Richard (2007). Crime and the American Dream. Thomson/Wadsworth.

- ^ Messner, Steven; Rosenfeld, Richard (2015). Translated by MOUSANEJAD, ALI. "THE VIRTUES AND VICES OF THE AMERICAN DREAM". Ilam Culture. 14 (38–39): 209–218.

Further reading

- Adams, James Truslow. (1931). The Epic of America (Little, Brown, and Co. 1931)

- Brueggemann, John. Rich, Free, and Miserable: The Failure of Success in America (Rowman & Littlefield; 2010) 233 pages; links discontent among middle-class Americans to the extension of market thinking into every aspect of life.

- Chomsky, Noam. Requiem for the American Dream: The 10 Principles of Concentration of Wealth & Power. Seven Stories Press, 2017. ISBN 978-1609807368

- Chua, Chen Lok. "Two Chinese Versions of the American Dream: The Golden Mountain in Lin Yutang and Maxine Hong Kingston," MELUS Vol. 8, No. 4, The Ethnic American Dream (Winter, 1981), pp. 61–70 in JSTOR

- Churchwell, Sarah. Behold, America: The Entangled History of 'America First' and 'the American Dream' (2018). 368 pp. online review

- Cullen, Jim. The American dream: a short history of an idea that shaped a nation, Oxford University Press US, 2004. ISBN 0-19-517325-2

- Hanson, Sandra L., and John Zogby, "The Polls – Trends", Public Opinion Quarterly, Sept 2010, Vol. 74, Issue 3, pp. 570–584

- Hanson, Sandra L. and John Kenneth White, ed. The American Dream in the 21st Century (Temple University Press; 2011); 168 pages; essays by sociologists and other scholars how on the American Dream relates to politics, religion, race, gender, and generation.

- Hopper, Kenneth, and William Hopper. The Puritan Gift: Reclaiming the American Dream Amidst Global Financial Chaos (2009), argues the Dream was devised by British entrepreneurs who build the American economy

- Johnson, Heather Beth. The American dream and the power of wealth: choosing schools and inheriting inequality in the land of opportunity, CRC Press, 2006. ISBN 0-415-95239-5

- Levinson, Julie. The American Success Myth on Film (Palgrave Macmillan; 2012) 220 pages

- Lieu, Nhi T. The American Dream in Vietnamese (U. of Minnesota Press, 2011) 186 pages ISBN 978-0-8166-6570-9

- Ownby, Ted. American Dreams in Mississippi: Consumers, Poverty, and Culture 1830–1998 (University of North Carolina Press, 1999)

- Samuel, Lawrence R. The American Dream: A Cultural History (Syracuse University Press; 2012) 241 pages; identifies six distinct eras since the phrase was coined in 1931.

External links

- 1930s neologisms

- American culture

- American exceptionalism

- History of the American West

- Social class in the United States

- Socio-economic mobility

- Virtue