Analytic theology

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Analytic theology (abbreviated AT) refers to a growing body of theological literature resulting from the application of the methods and concepts of late-20th-century analytic philosophy. In the last decade, various lectures, study centers, conference sections, academic journals, and at least one monographic series has appeared with "Analytic Theology" in their title or description. The movement counts both philosophers and theologians in its ranks, but a growing number of theologians with philosophy training produce AT literature. Analytic theology is strongly related to the philosophy of religion, but it is wider in scope due to its willingness to engage topics not normally addressed in the philosophy of religion (such as the Eucharist, sin, salvation, and eschatology). Given the types of historical philosophy that have funded the analytic philosophy of religion, theologians are frequently involved in retrieval theology as they revisit, re-appropriate, and modify older Christian solutions to theological questions. Analytic theology has strong roots in the Anglo-American analytic philosophy of religion in the last quarter of the 20th century, as well as similarities at times to scholastic approaches to theology. However, the term analytic theology primarily refers to a resurgence of philosophical-theological work during the last 15 years by a community of scholars spreading outward from centers in the UK and the US.[citation needed]

Defining analytic theology[]

Historically and methodologically, AT is both a way of approaching theological works as well as a sociological or historical shift in academic theology.

Analytic theology defined as a theological method[]

Due to its similarities to philosophical theology and philosophy of religion, defining analytic theology has been a challenge. Systematic theologian William J. Abraham defines analytic theology as “systematic theology attuned to the deployment of the skills, resources, and virtues of analytic philosophy. It is the articulation of the central themes of Christian teaching illuminated by the best insights of analytic philosophy.”[1] Philosopher Michael Rea defines analytic theology as “the activity of approaching theological topics with the ambitions of an analytic philosopher and in a style that conforms to the prescriptions that are distinctive of analytic philosophical discourse. It will also involve, more or less, pursuing those topics in a way that engages the literature that is constitutive of the analytic, employing some of the technical jargon from that tradition, and so on. But, in the end, it is the style and the ambitions that are most central.”[2] Cambridge theologian Sarah Coakley, by contrast, warns that attempts to set down an essentialist definition for analytic theology (i.e. a club that some are in and some are not welcome in) will distract from the productive work resulting from the recent flourishing of AT.[3]

More specifically, analytic theology can be understood in a narrow and wide sense. When understood more widely, analytic theology is a method to be applied in theological works. Like other methodological approaches to theology (e.g. historical theology, retrieval theology, post-liberal theology), analytic theology, in this view, is a way of doing theological work that is independent of one's theological commitments. In this wider sense, Muslims, Jews, and Christians could all apply the same analytic methods to their theological work. William Wood has called this the “formal model” of analytic theology.[4]

By contrast, some are concerned that those participating in the analytic theology movement are doing more than just applying a particular method to their work. Given that most of its practitioners are Christians, they wonder if analytic theology is also a theological program (i.e. it is committed to forwarding a certain body of theological beliefs). This then would be the narrower sense of analytic theology. In contrast to the formal method above, Wood suggests we could call this wider sense the “substantive model” of analytic theology. Here one does “theology that draws on the tools and methods of analytic philosophy to advance a specific theological agenda, one that is, broadly speaking, associated with traditional Christian orthodoxy. On this conception, the central task of analytic theology would be to develop philosophically well-grounded accounts of traditional Christian doctrines like the Trinity, Christology, and the atonement.” Wood is correct that the majority of analytic theologians are Christians who write in support of a broadly conciliar Orthodoxy. However, until statements by Christian analytic theologians can be cited that reject non-Christian (or even unorthodox Christian) conclusions as falling outside the boundaries of analytic theology, the “substantive model” may lack justification as a fair definition.

Falling between these two poles may be a more moderate position. Oliver Crisp, one of the founders of the contemporary AT movement, comments that AT is indeed more than just a theological style of writing. It also involves work by theologians who hold that “there is some theological truth of the matter and that this truth of the matter can be ascertained and understood by human beings (theologians included!).” Such writers also hold to “instrumental use of reason.”[5] Crisp's comment brings out a key attribute of analytic theology addressed below - a tendency towards theological realism.

Whether one holds a wide, narrow, or moderate view of analytic theology, “doing” analytic theology does not require undergoing a religious experience, participating in a church, or holding to any confessional statement. This openness makes more sense in contrast to the idea of doctrine, which involves the clarification and advancement of the teachings of a particular church or Christian community.

Characteristics of analytic theology[]

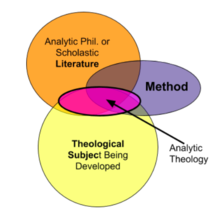

As a way of doing theology, analytic theology can often be identified by at least two, but usually three features: First there is the analytic method itself. Second is the focus on theological topics, such as incarnation or resurrection. There is not a hard boundary between analytic theology and analytic philosophy of religion. However, as noted in the introduction, analytic theology tends to treat a wider range of theological topics than the philosophy of religion. Whereas the latter might limit its focus to the existence of God, the problem of evil, and a very minimal concept of God (i.e. omniscience, omnipotence, omnibenevolence). Analytic Theologians assume the existence of God and press well into the analysis of theological topics not often addressed by the philosophy of religion. The third feature that characterizes most analytic theology is an engagement with the wider analytic philosophical or theological literature for concepts that can be applied to answer theological questions. Very often these concepts are deployed in the process of solving questions or conceptual “problems” that accompany certain theological beliefs (e.g. the two natures of Christ, or the question of free will in heaven). This literary aspect may be as essential as the other two. For example, ideas such as speech-act theory or possible worlds semantics have been applied to theological questions involving divine revelation or foreknowledge. In other words, analytic theology involves not only theology was written about with a certain analytic style but an application of ideas found in the analytic philosophical literature.

The analytic method[]

The most frequently mentioned characteristic of analytic theology is its broad methodological and thematic overlap with analytic philosophy. This is signaled by the shared term “analytic” in both phrases. An effort to sketch out, tentatively, some rhetorical features that characterised analytic philosophy was first made by philosopher Michael Rea in the introduction to the 2009 edited volume Analytic Theology.[6] The idea was that some of these ways of pursuing an analysis of topics are found to characterize analytic theology. Rae's five characteristics are:

- P1. Write as if philosophical positions and conclusions can be adequately formulated in sentences that can be formalized and logically manipulated.

- P2. Prioritize precision, clarity, and logical coherence.

- P3 Avoid substantive (non-decorative) use of metaphor and other tropes whose semantic content outstrips their propositional content.

- P4 Work as much as possible with well-understood primitive concepts, and concepts that can be analyzed in terms of those.

- P5 Treat conceptual analysis (insofar as it is possible) as a source of evidence.

(Rea's qualification of each of these principles as well as his discussion of disagreements over them should be consulted):

Imagine, for example, that a theologian writes that Jesus's cry of dereliction from the cross indicates that the Trinity was broken or ruptured mysteriously during Jesus' crucifixion. First, in terms of differentiating AT from the philosophy of religion, this is not something likely to be addressed in the philosophy of religion. An analytic theologian might ask for what “broken” denotes given its connotations when used about the God of Christianity. Is the original writer merely using rhetorical flair or are they trying to imply an actual ontological change in God? The analytic theologian, given her penchant for theory building, might list out the implications for other Christian doctrines depending on what meaning is intended by the word “broken.” The analytic theologian might turn to the history of theology, philosophically careful theologians, in search of concepts that help her speak about Christ being “forsaken” by God without doing so in a way that unnecessarily risks contradicting an orthodox understanding of the Trinity.[7]

Analytic writers are willing to agree with others that many things about God easily outstrip our conceptual abilities. Mystery or apophatic is not incompatible with Analytic Theology. However the latter is more likely than others to press back when such concepts are used in a way that seems unnecessarily incoherent or risks contradicting other doctrines.

Analytic theology defined sociologically and historically[]

Andrew Chignell has offered a different definition of analytic theology: “analytic theology is a new, concerted, and well-funded effort on the part of philosophers of religion, theologians, and religion scholars to re-engage and learn from one another, instead of allowing historical, institutional, and stylistic barriers to keep them apart.”[8] This definition is seen as significant because in some senses analytic theology is not substantially different methodologically than philosophical theology work done in the 1980s and 1990s. For example, Thomas V. Morris's books The Logic of God Incarnate (1986) and Our Idea of God (1991) exemplify the method and style of those working in analytic theology, but predates the current trend by twenty years.

From this perspective, what characterizes analytic theology is sociological as much as methodological. In addition to its stylistic features, analytic theology is a reconciliation between philosophers, theologians, and biblical studies scholars that were less present before the mid-2000s. Chignell mentions at least two edited volumes that attempted to bring together philosophers, theologians and scholars of religion to work on questions they had in common.[9] It is difficult to say why the analytic theology movement did not gain momentum prior to Crisp and Rea's efforts between 2004 and the 2009 publication of Analytic Theology. In their respective fields, Crisp and Rea both witnessed a lack of eagerness for interdisciplinary interaction between philosophy and theology.[10] One possibility for the delay is that more time was needed (in the mid-1990s) before works by Richard Swinburne, Thomas Flint, Nicholas Wolterstorff, Eleonore Stump, Alvin Plantinga, and others made room in the theological academy for a movement like analytic theology.

An alternative, and significant factor, is the role the John Templeton Foundation played in funding projects connected with analytic theology. It is not inconsequential that the John Templeton Foundation has helped to fund analytic theology-type projects on three continents, including North America, at the University of Notre Dame's Center for Philosophy of Religion; in Europe, at the Munich School of Philosophy and University of Innsbruck; and, in the Middle East, at the Shalem Center and then later the Herzl Institute in Jerusalem. More recent Templeton-funded initiatives include a three-year project at Fuller Theological Seminary in California and the establishment of Logos Institute for Analytic and Exegetical Theology at the University of St. Andrews, Scotland.”[11]

Whatever the link between the rise of AT and funding might be, it is unlikely that funding alone accounts for the flourishing in work that has appeared in the last decade. It certainly has nothing to do with the rich precursors to the AT movement in the 1980s and 1990s. For this reason, understanding the 20th-century shifts in Anglo-American philosophy is important to understanding the appearance of analytic theology.

The history of analytic theology[]

Historically demarcating movements (e.g. the Early Modern period of European history) is always imperfect. Many intellectual movements rise and fall like a bell curve rather than appearing suddenly as with clear boundaries. Analytic theology is no different. It should be thought of as the result of a wave cresting and not the result of a few contemporary individuals. Those currently working analytic theology derive their momentum from previous scholarship.

Contemporary analytic theology, represented by scholars like Oliver Crisp and Michael Rea, has its roots in three periods of Western philosophical history. These are indicated by the three “rising tide” levels in Figure 2. These periods include: (a) historic Scholastic philosophical theology (b) Mid 20th century responses by Christian philosophers to challenges of religious epistemology and religious language about God (c) a turn by Christian philosophers to work on more traditionally theological topics in the 1980s.

As noted above, analytic theology is a contemporary movement. It is a resurgence in philosophical-theology that began in the UK and the US. However, this movement has always had a strong retrieval element to it. Retrieval theology refers to thinkers revisiting and reappropriating certain ideas from historical theology or philosophy. In analytic theology, this retrieval often includes a revisitation to the works of theologian-philosophers like Augustine, Duns Scotus, Anselm, Thomas Aquinas, and Jonathan Edwards. How then did a contemporary movement wind up with roots in a period of the Western intellectual tradition that is hundreds of years old?

In Medieval Europe, a rich tradition of philosophical thought about theological topics flourished for over a thousand years. This tradition of philosophical theology was brought into steep decline by the philosophy of Immanuel Kant and the theology of Friedrich Schleiermacher.[12] In the 20th-century, logical positivism stands as the low water-mark of philosophical theology with its denial of the very possibility to talk meaningfully about God at all. As a result, a very robust dividing wall separated philosophy and theology by the middle of the 20th century. (See Figure 2). The story of analytic theology usually begins at this point with Logical Positivism.

In August 1929, a group of philosophers in Vienna sometimes referred to as the Vienna Circle, published a manifesto containing a verificationist criterion to be used as a criterion by which statements could be analyzed in terms of meaning. Any statements that could not be broken down into empirically verifiable concepts were held to be meaningless thus preventing any metaphysical (i.e. theological) dialogue as counting as meaningful.

In the middle of the 20th century this verification principle began to crumble under the weight of its strictness on at least four counts: (a) No satisfactory concept of empirical verifiability could be agreed upon; (b) Supporters of logical positivism like Carl Hempel argued that it seemed to invalidate less strictly worded universal generalizations of science; (c) Ordinary language philosophers argued that it rendered meaningless imperatives, interrogatives, and other performative utterances.[13] (d) Furthermore, the verification principle itself was not empirically verifiable by its own standards.

By the 1950s logical positivism was in decline and with it the stance that metaphysical claims were meaningless. The conversation shifted to grounds that required speakers to show why theological or philosophical claims were true or false. This had a liberating effect on analytic philosophy.[14] According to Nicholas Wolterstorff, the demise of Logical Positivism also had the effect of throwing doubt over other attempts, such as those of Kant or the Logical Positivists, to point out a deep epistemological boundary between the knowable and unknowable, the thinkable and unthinkable. This put a crack in the wall that had divided theology and philosophy for centuries. Wolterstorff states that one result of the demise of logical positivism “has proved to be that the theme of limits on the thinkable and the assertible has lost virtually all interest for philosophers in the analytic tradition. Of course, analytic philosophers do still on occasion charge people with failing to think a genuine thought or make a genuine judgment. But the tacit assumption has come to be that such claims will always have to be defended on an individual, ad hoc, basis; deep skepticism reigns among analytic philosophers concerning all grand proposals for demarcating the thinkable from the unthinkable, the assertible from the non-assertible.”[15] Wolterstorff also suggests that classical-foundationalism collapsed as the de facto theory of epistemology in philosophy, but it was not replaced by an alternative theory. What has resulted was an environment of dialogical pluralism where no major epistemological framework (e.g. classical foundationalism or idealism) is widely held.[16]

In this context of dialogical pluralism, the state of play returned to one in which metaphysical or theistic belief could be taken as rational provided one could give justification for those beliefs. Two mechanisms for doing this became popular: Reformed Epistemology (See. Alvin Plantinga & Nicholas Wolterstorff) and evidentialist approaches that made use of Bayesian probability (See. Richard Swinburne). Either way, logical argumentation, and rational coherence remained important for such beliefs.[17] In addition to arguments for rational belief in God, Christian philosophers also began to give arguments for the rationality of various aspects of belief within a theistic worldview. Examples here would be the coherence of certain traditional attributes of God or the possibility that the existence of God was not logically incompatible with the existence of evil in the world).

In 1978, the [Society of Christian Philosophers] was formed. Six years later Alvin Plantinga delivered his famous presidential addresses “Advice to Christian Philosophers” in which he signaled the need for Christians working in that field to do more than follow the assumptions and approaches to philosophy accepted in the wider field, given that many of those assumptions were antithetical to Christianity. He goes on to write that

Christian philosophers, however, are the philosophers of the Christian community; and it is part of their task as Christian philosophers to serve the Christian community. But the Christian community has its questions, its own concerns, its own topics for investigation, its agenda, and its research program. Christian philosophers ought not merely to take their inspiration from what's going on at Princeton or Berkeley or Harvard, attractive and scintillating as that may be; for perhaps those questions and topics are not the ones or not the only ones, they should be thinking about as the philosophers of the Christian community. There are other philosophical topics the Christian community must work at, and other topics the Christian community must work at philosophically. And obviously, Christian philosophers are the ones who must do the philosophical work involved. If they devote their best efforts to the topics fashionable to the non-Christian philosophical world, they will neglect a crucial and central part of their task as Christian philosophers. What is needed here is more independence, more autonomy concerning the projects and concerns of the non-theistic philosophical world.[18]

In the 1980s and 1990s Christian philosophers did begin to turn much of their efforts to explicating questions unique to Christian theology, thereby setting the precedent for the type of work done in analytic theology. The decades saw the production of more literature by Christian philosophers treating theological topics such as the attributes of God the atonement by scholars like [Richard Swinburne]. However, much of that work remained largely appreciated by Christian philosophers and less so by Christian theologians. As noted in the analytic theology Defined as a Movement section, both Oliver Crisp and Michael Rea found that philosophers and theologians were not interacting and sharing resources as late as the mid-2000s. It was in the mid-2000s at Notre Dame that they floated the idea of an edited volume aimed at bringing philosophers and theologians together to work on theological questions with a methodology tuned to the style and resources of analytic philosophy.

As we discussed the matter, we thought that perhaps a volume might be called for a volume tendentiously entitled Analytic Theology, which would include a few essays making a case directed toward theologians on behalf of analytic approaches to theological topics, a few essays that offered criticism of such approaches, and a few more essays that addressed some of the historical, methodological, and epistemological issues that seemed to lurk in the background of the disciplinary divide. Broadly speaking, our primary task in the volume was to say a bit about what we take “analytic theology” to consist in, and then to make a sort of cumulative case in favor of its being a worthwhile enterprise.[19]

It was with the publication of this volume that AT began to garner attention, both positive and negative, in philosophical and theological circles. In 2012, a session at the American Academy of Religion was dedicated to discussing the volume, followed by several articles in volume 81 the AAR journal. In 2013 the Journal of analytic theology was begun, which is now in its sixth year. In 2015, Thomas McCall, professor of Theology at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School published An Invitation to Analytic Christian Theology with IVP. The following year at the 2016 Evangelical Theological Society annual conference a series of papers were given interacting with McCall's book to a packed room. By the close of the second decade of the 21st-century, several multiple-year projects have been funded at graduate-level institutions that focus on Analytic Theology. Edited volumes, such as those in the Oxford Studies in analytic theology series, continue to be released. Several dissertations have now been published, like monographs, that treat theological topics in an Analytic Style, and both the AAR and ETS continue to have regular sections devoted to papers on Analytic Theology.

Analytic theology compared to other disciplines[]

In a 2013 volume of the Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Andrew Chignell notes that some of the reviewers and writers in the 2009 analytic theology edited volume wondered what the difference, if any, was between analytic theology and philosophical theology.[20] Chignell's definition brings out an important question. Similarly one might ask what the difference between analytic theology and the Analytic Philosophy of Religion is.[21] Demarcating boundaries between disciplines can be difficult. This is no different from analytic theology. Therefore, suggestions will be disputed. However, here are a few distinctions.

- Analytic theology versus philosophical theology. The difference between Analytic Theology and philosophical theology is largely sociological or historic. Analytic theology just is philosophical theology applied by theologians with philosophical methods and sensitivities. In time, as analytic theologians listen to the calls by Biblical Theologians to be more sensitive to exegetical issues, there might develop a slight difference between even philosophical theology and analytic theology.

- Analytic theology versus the philosophy of religion. The difference between Analytic Theology and the philosophy of religion, is more of a difference in scope. Given that AT grew out of Anglo-American philosophy of religion, they share much of the same history up until the 1990s. However, Analytic Theology is willing to treat topics of Christian theology that one will not see addressed in the philosophy of religion. Furthermore, analytic theologians are not focused on proving the existence of God. Instead, they will begin with God's existence, and the deliverances of their particular Christian tradition, and work on theological questions with the tools of analytic philosophy. Andrew Chignell suggests something like this in writing:

Philosophy of religion involves arguments about religiously pertinent philosophical issues, of course, but these arguments are customarily constructed in such a way that, ideally, anyone will be able to feel their probative force based on ‘reason alone.’ Analytic theology, by contrast, appeals to sources of topics and evidence that go well beyond our collective heritage as rational beings with the standard complement of cognitive faculties.[22] In addition to creating a wider range of topics than the philosophy of religion, and focusing on a slightly narrower audience, AT may differ from the philosophy of religion in the way it makes use of Scripture and tradition as evidence in its methodology.[23]

- Analytic theology versus systematic theology. The difference between analytic theology and systematic theology is a third question that has been raised. Michael Rea's introduction in the 2009 analytic theology volume has not been received well by some theologians. Analytic Theology has thus been challenged as legitimately theology. Some suspect it is no more than philosophy in theological costume. William Abraham argues that analytic theology is systematic theology and that it was only a matter of time before something like analytic theology took root in the theological world.[24] Oliver Crisp has published an article demonstrating how analytic theology could qualify itself as systematic theology. Crisp cites leading theologians to demonstrate that there is no agreed-upon definition for systematic theology. He then shows how analytic theology shares a common task and goals with systematic theology and rises above a conceptual threshold established by the way various theologians view systematic theology.[25] In a 2017 interview, Oliver Crisp suggests that analytic theology is not attempting to take over the work of theology, but is instead suggesting an additional set of resources that theologians could turn to find help in their theological projects.[26]

Analytic theology thus sits at the boundaries between several disciplines as suggested by Figure 3.

Motivations for analytic theology[]

Why would students and scholars want to do theological work in an analytic style? At least three motivations exist:

- A motivation to find possible solutions to theological challenges. The history of theology has demonstrated that times of disagreement during the church's history have produced advances in theological clarity and depth. Theological disagreements force parties to be clear about their terminology, thought processes, and values. Disagreement also motivates thinkers to look for new solutions to prior conceptual problems. During the 20th-century, challenges to Christian theology by many thinkers like Anthony Flew, William Rowe, and John Hick provoked responses by philosophers like Basil Mitchell, Alvin Plantinga, and Thomas Morris which proved to be valued by many Christian theologians. By way of example, Christians have held for centuries that God answers petitionary prayer. More than one philosopher has offers a strong argument for the incompatibility of answered prayer and divine foreknowledge. It is easy to see a strong desire for a solution to the puzzle. Analytic theology, thanks to its careful way of proceeding and its access to philosophical concepts, offers conceptual tools to work out explanations to solutions, rather than just asserting that answered prayer is possible (e.g. rather than merely citing Bible passages like James 5:15-18).

- A motivation to consider theological topics and challenges from a fresh perspective. Some theological words (e.g. love, judgment) are widely used without reflection because they are part of everyday language. However, clarifying what words like “love” refer to (rather than mistaking the effects of love for the meaning of “love” ) can bring a fresh perspective to old discussions. Christians might know for example that God loves us and that the evidence of love is patience and kindness. If love is defined as a desire for the good of the beloved and union with the beloved (and insight from Thomas Aquinas) new vistas of thought open up. One suddenly has criteria by which to identify patient actions that are genuinely loving patient and kind acts that are driven by other motives.

- A motivation to reap the benefits of clearer thinking in theological writing. When responding to conceptual challenges, writers sometimes offer “solutions” that, in hindsight, turn out to be new terms that do little more than renaming the problem or put a new label on an old solution. The clear and careful thinking, prized by analytic theologians, can alert others to these dead ends by calling writers to clarify the meanings masked by new terminology, or to demonstrate the difference between new terms and already existing “solutions.”

Criticisms of analytic theology[]

Some of the following concerns have been voiced over analytic theology. First, “Why do analytic theologians have such conservative theological views?” In other words, is AT just a theological project? Second, “Why do analytic theologians ignore historical-critical biblical studies?” The worry here is also stated as, "Analytic Theologians seem to treat the Bible as a sourcebook for propositions to insert into logical arguments." Thirdly, similar to the second worry, "Does AT genuinely engage Biblical narrative?" Fourth, "Is Analytic Theology genuinely theology or is it just philosophy dressed in theological clothing?"

Practitioners & examples of analytic theology[]

One of the best ways to become acquainted with a style of work or a movement is to become acquainted with works that are considered to be good examples of that style. As noted in the article above, before the mid-2000s most of the scholars doing something like analytic theology were Christian philosophers working on their own projects.

Practitioners[]

Given its dual citizenship in theology and philosophy, nothing prevents philosophers, with theological skills, or theologians, with philosophical training, from doing analytic theology. One should expect the scholar's particular strengths, theology versus philosophy, to take the leading role in their writing. Some of the best work resourced by analytic theologians have been done by philosophers, including nearly all of the past presidents of the Society of Christian Philosophers. Although artificial, an attempt to list out some leading lights in terms of “generations”

- 1st Generation (Writers who released their first works in the 1960-70s.) Basil Mitchell, Nicholas Wolterstorff, George Mavrodes, Alvin Plantinga, Richard Swinburne

- 2nd Generation (Writers who released their first works in the 1980s.) Plantinga/Wolterstorff/Swinburne again, William Hasker, Thomas Flint, Linda Zagzebski, Eleonore Stump, Thomas Morris, James P. Moreland, William J. Abraham

- 3rd Generation (Writers who released works in the 1990s and 2000s) Oliver Crisp, Michael Rea, Thomas McCall, Trent Doughtery, Brian Leftow, Sarah Coakley, etc..

- 4th Generation (Writers who released works in the last decade) Tim Pawl, Jonathan C Rutledge, Joshua Cockayne, Joshua Farris, JT Turner, James Arcadi, Jordan Wessling, Aku Visala, R.T. Mullins, Kevin Hector, RC Kunst, etc....

Examples[]

The literature representative of analytic theology is growing rapidly. A few examples include: Analytic Theology: New Essays in the Philosophy of Theology (2009) edited by Oliver Crisp and Michael Rea; Analytic Theology: A Bibliography (2012) by William Abraham, An Invitation to Analytic Christian Theology (2015) by Thomas H. McCall; the Journal of Analytic Theology, the TheoLogica journal. Interested scholars should consult the growing series of titles under the Oxford Studies in Analytic Theology. There are nine titles in the series as of 2018.[27] The PBS series Closer to Truth, released an episode on analytic theology in 2018. Finally, as noted in the sections on the history of analytic theology, there is a much wider body of literature published between 1970 and the 2009 release of the analytic theology that represents the kind of work analytic theologians value and use in their more recent works.

Geography of analytic theology[]

Given the above history, it is not unreasonable to suggest that analytic theology had its birth in an Anglo-American world of analytic philosophy. This is in contrast to the German idealist context of much early 20th-century theology (e.g. Karl Barth, Karl Rahner). Since the publication of the 2009 analytic theology volume, and with the help of several Templeton grants, analytic theology is being done in the UK, US, Germany, and Israel. Individual scholars who would count themselves as Analytic Theologians, or supporters of AT, can be found at institutions in the following countries or regions: Spain, Israel, Brazil, France, the UK, Austria, Scandinavia, and North America.

Currently, there are several centers of study where analytic theology is being actively worked on in a departmental setting. These include: Fuller Theological Seminary, the Logos Institute at St. Andrews University, the Center for Philosophy of Religion at Notre Dame University, Oriel College at Oxford and the University of Innsbruck.[28]

References[]

- ^ William J. Abraham, “Systematic Theology as Analytic Theology,” in Analytic Theology: New Essays in the Philosophy of Theology, ed. Oliver Crisp and Michael C. Rea (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 54.

- ^ Michael C. Rea, “Introduction,” in Analytic Theology: New Essays in the Philosophy of Theology, ed. Oliver Crisp and Michael C. Rea (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 7.

- ^ Sarah Coakley, “On Why Analytic Theology Is Not a Club,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 81, no. 3 (September 1, 2013): 604-605.

- ^ William Wood, “Trajectories, Traditions, and Tools in Analytic Theology,” Journal of Analytic Theology 4 (2016): 255

- ^ Oliver Crisp, “On Analytic Theology,” in Analytic Theology: New Essays in the Philosophy of Theology, ed. Oliver Crisp and Michael C. Rea (Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 35.

- ^ Oliver Crisp and Michael C. Rea, eds., Analytic Theology: New Essays in the Philosophy of Theology (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2009).

- ^ See, for example, Thomas H. McCall, Forsaken: The Trinity and the Cross, and Why It Matters (Downers Grove, Ill: IVP Academic, 2012).

- ^ Andrew Chignell, “The Two (or Three) Cultures of Analytic Theology: A Roundtable,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 81, no. 3 (September 1, 2013): 570. Emphasis removed.

- ^ See Eleonore Stump and Thomas P. Flint, eds., University of Notre Dame Studies in the Philosophy of Religion, vol. 7, "Hermes and Athena: Biblical Exegesis and Philosophical Theology" (Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1993). See also, William J. Wainwright, ed., Reflection and Theory in the Study of Religion, vol. 11, "God, Philosophy, and Academic Culture: a Discussion between Scholars in the AAR and the APA" (Atlanta, Ga.: Scholars Press, 1996).

- ^ Michael Rea, “Analytic Theology: Precis,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 81, no. 3 (September 1, 2013): 573.

- ^ Joshua R. Farris and James M. Arcadi, “Introduction to the Topical Issue ‘Analytic Perspectives on Method and Authority in Theology,’” Open Theology 3, no. 1 (November 27, 2017), 630.

- ^ See Nicholas Wolterstorff, “Is It Possible and Desirable for Theologians to Recover from Kant?,” Modern Theology 14, no. 1 (January 1998).

- ^ Georg Gasser, “Toward Analytic Theology: An Itinerary,” Scientia et Fides 3, no. 2 (November 4, 2015): 27.

- ^ Gasser, “Toward Analytic Theology,” 31.

- ^ Nicholas Wolterstorff, “How Philosophical Theology Became Possible within the Analytic Tradition of Philosophy,” in Analytic Theology: New Essays in the Philosophy of Theology, ed. Oliver Crisp and Michael C. Rea (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 157.

- ^ Wolterstorff, “How Philosophical Theology Became Possible,” 159-161.

- ^ Gasser, “Toward Analytic Theology”, 44.

- ^ Alvin Plantinga, “Advice to Christian Philosophers,” Faith and Philosophy 1, no. 3 (1984): 253–271.

- ^ Michael Rea, “Analytic Theology: Precis,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 81, no. 3 (September 1, 2013): 573.

- ^ Andrew Chignell, “The Two (or Three) Cultures of Analytic Theology: A Roundtable,” Journal of the American Academy of Religion 81, no. 3 (September 1, 2013): 569–570.

- ^ Max Baker-Hytch, “Analytic Theology and Analytic Philosophy of Religion: What’s the Difference?,” Journal of Analytic Theology 4 (May 2016): 347.

- ^ Andrew Chignell, “As Kant Has Shown,” in Analytic Theology: New Essays in the Philosophy of Theology, ed. Oliver Crisp and Michael C. Rea (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 119.

- ^ Max Baker-Hytch presses on this last possible difference by calling Analytic Theologians to specify exactly what it is about its use of Scripture and tradition that distinguishes it from the philosophy of religion. See Max Baker-Hytch, “Analytic Theology and Analytic Philosophy of Religion: What’s the Difference?,” Journal of Analytic Theology 4 (May 2016): 347-361.

- ^ William J. Abraham, “Systematic Theology as Analytic Theology,” in Analytic Theology: New Essays in the Philosophy of Theology, ed. Oliver Crisp and Michael C. Rea (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 54–69.

- ^ Oliver D. Crisp, “Analytic Theology as Systematic Theology,” Open Theology 3, no. 1 (January 26, 2017): 156–166.

- ^ See https://www.closertotruth.com/episodes/what-analytic-theology

- ^ See https://global.oup.com/academic/content/series/o/oxford-studies-in-analytic-theology-osat/

- ^ See Innsbruck: www.uibk.ac.at/analytic-theology/; Fuller Seminary: analytictheology.fuller.edu; St. Andrews: logos.wp.st-Andrews.ac.uk; and Notre Dame: philreligion.nd.edu/research-initiatives/analytic-theology.

- Theology