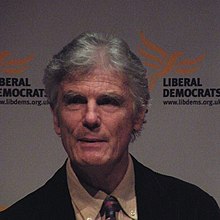

Andrew Phillips, Baron Phillips of Sudbury

This article uses bare URLs, which may be threatened by link rot. (May 2021) |

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (December 2020) |

The Lord Phillips of Sudbury | |

|---|---|

| |

| Chancellor of the University of Essex | |

| In office 28 April 2003 – 21 July 2014 | |

| Vice-Chancellor | Ivor Crewe Colin Riordan Anthony Forster |

| Preceded by | The Lord Nolan |

| Succeeded by | The Baroness Chakrabarti |

| Member of the House of Lords Lord Temporal | |

| In office 25 July 1998 – 7 May 2015 Life peerage | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 15 March 1939 Long Melford, Suffolk, England, UK |

| Political party | Liberal Democrats |

| Spouse(s) | Penelope Ann Bennett |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | Trinity Hall, Cambridge |

| Occupation | British solicitor and politician |

Andrew Wyndham Phillips, Baron Phillips of Sudbury, OBE (born 15 March 1939) is a solicitor and Liberal Democrat politician.

Education; legal practice[]

Andrew Phillips attended Culford School, Uppingham School and Trinity Hall, Cambridge, where he read Economics and Law, then qualified as a solicitor in 1964, eventually specialising in charity law.[1] For two years before university he worked as an office boy in his father's law firm in their home town of Sudbury, Suffolk, and after qualifying he worked initially as a salaried partner in two leading law firms in London – Pritchard Englefield and then Lawford & Co.[2] In 1970 he founded commercial law firm Bates Wells Braithwaite,[3] giving it the same name as his father's firm, though it was an entirely independent entity.

He had several long-running battles with the Charity Commission to secure charitable status for organisations including the Fairtrade Foundation, the Village Retail Stores Association, Charity Bank and Switchboard (previously the London Lesbian and Gay Switchboard) (1974).

Phillips also represented Richard Harries, the Bishop of Oxford, in a case against the Church Commissioners over ethical investment of their assets. Harries challenged the Commissioners to change their investment policy, arguing that the Church ought not to invest in assets that were incompatible with the promotion of the Christian faith, even if it involved financial detriment. The now-famous case was not considered a win for the Bishop at the time, but the action did pave the way for a more permissive environment for charities to invest ethically if they wish.

Outside of charities, one early client of Bates Wells Braithwaite in London was noted inventor James Dyson. Phillips advised him on the setting up of his first company, Kirk-Dyson Designs, and also became a director and shareholder of that entity. However, Phillips later sold his stake back to Dyson for the same sum he'd paid for it – just a few years before Dyson's vacuum cleaners burst onto the UK market and made their designer a very wealthy man.[4]

Phillips stepped down as senior partner of Bates Wells Braithwaite when he joined the House of Lords in 1998. An article in The Times in 2012 described him as "one of the most identifiable and respected English lawyers of his generation.[2]

Broadcasting and publishing[]

From 1976, he appeared on BBC Radio 2’s Jimmy Young Show as the "legal eagle," giving legal advice to the show's listeners. He continued in this role until the show ended upon Sir Jimmy's retirement in 2002. In 1981 and 1982 Phillips presented 30 episodes of The London Programme, a current affairs show on London Weekend Television.[5] He has also appeared on other television and radio programmes such as Any Questions?, A Week in Politics, The Sunday Programme and Newsnight.

From 1992 until 2002 Phillips was on the board of the Scott Trust, owner of The Guardian, where he advocated strongly for its acquisition of The Observer. He has also written numerous blogs for The Guardian[6] and wrote a monthly law column for Good Housekeeping.

He was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 1996 New Year Honours.

Phillips was appointed Chancellor of the University of Essex on 28 April 2003, succeeding Lord Nolan who had retired on 31 December 2002. He retired from the position in July 2013.[7]

Charity work[]

Phillips was co-founder and first chairman of the Legal Action Group in 1971, and also in the same year co-founded The Parlex Group of trans-Europe lawyers.[1] He co-founded the Solicitors Pro Bono Group (LawWorks) in 1996, and remains President.[1]

Phillips was a member of first board of the Community Fund, distributing National Lottery funds. From 1992 to 2002 he was a member of Scott Trust, which owned The Guardian and other media.[1]

Concerned by young people's lack of knowledge about their rights and responsibilities as citizens, Phillips secured funding from The Law Society to set up the Law in Education Project in 1985, to create educational resources for schools. In 1989, the Citizenship Foundation was founded out of this project. Phillips remains President of the Citizenship Foundation (renamed Young Citizens in 2018).[8][9][10]

Political work and House of Lords[]

Phillips was originally a member of the Labour Party, and contested the 1970 General Election for Labour in Harwich. But he was expelled from the party in 1973 for publishing a letter in The Times deploring the party's policy of nationalising the top 100 companies and indemnifying trade unionists with criminal convictions,[11] and joined the Liberals in the early 1970s. He later stood as a Liberal candidate in Saffron Walden in both a 1977 by-election and the 1979 General Election, and later stood as a Liberal in Gainsborough and Horncastle in 1983. He also contested the first European Parliament elections as a Liberal in 1979, in North Essex.

When he stood as a Liberal candidate in the first-ever European elections in 1979, Phillips declared that the EU was out of touch with ordinary people and needed to become more democratic. In 2001, he proposed an amendment to the European Communities (Amendment) Bill requesting that the government send a leaflet to every household in the UK, spelling out the impact of the Treaty of Nice, the accord which reformed the institutional structure of the European Union. Phillips had long complained that the government did nothing to explain the complexities of the EU to the public, and claimed it would cost less than £1.4 million to send a two-page tabloid freesheet to all 24.5 million households. He was not arguing for or against the EU or the Treaty, but appealing for a tool to help the public understand them. He voted to leave the EU in the 2016 referendum.[12]

On 25 July 1998, Phillips was made a life peer as Baron Phillips of Sudbury, of Sudbury in the County of Suffolk.[13][14] He sat in the House of Lords as a Liberal Democrat. He spoke on a wide range of issues but was especially concerned with civil liberties and charity law.

Phillips was one of six peers on the joint pre-legislative scrutiny committee of the Charities Bill and later led the response to it in the Lords, putting down over 200 amendments and having a significant impact on its final shape.

Uneasy at the growing trust deficit between government and its citizens, he helped to block the introduction of the Identity Cards Bill, which he regards as his proudest achievement in Parliament. The new law, tabled in 2004, would have made ID cards compulsory for every citizen, given the Home Secretary extensive powers to require copious details about people and their lives, and carried heavy penalties for non-compliance.

In July 2006, to the surprise of many people, Phillips announced his intention to resign from the House of Lords at the age of 67 (the average age of members being 68). He often criticised the cascades of legislation produced by Parliament, saying in 2012: “We are now legislating between 12,000 and 15,000 pages of new statute law a year and we repeal only about 2,000, 3,000 or 4,000 pages. We are legislating more than any respectable democracy in the western world by far. Dire consequences arise from having this excessive quantity of legislation, much of which is half baked and not implemented, or implemented unevenly."[15] He pointed out to the House of Lords during a debate on the Constitutional Reform and Governance Bill in 2010, that that Bill alone was longer than the entire legislative output of 1906.[16]

He had wanted to vacate his seat in the House of Lords, revert to being known as Mr Phillips, and allow "new blood" from his party to take his seat.[17] However, although hereditary peers may disclaim their titles under the Peerage Act 1963, life peers are unable to renounce their titles and continue to hold them for life. He introduced a Private Member's Bill permitting the resignation of life peers, but it failed.[18] Therefore, Phillips took leave of absence from the House, meaning he was unable to attend or vote, but could return at a month's notice. There was not automatically a seat for a new Liberal Democrat peer in the House. During his first spell in the Lords, he made 1,486 contributions over the eight years.[19]

In 2009, Phillips ended his leave of absence, returning to the Chamber to speak and vote once again. The House of Lords Reform Act (2014) allowed him finally to resign, which he did on 7 May 2015. During his 14 years in the Lords, he made 2,330 contributions.

Phillips led the Liberal Democrats’ opposition in the Lords to the government's Identity Cards Bill 2014, inflicting several defeats on the government.[20][21] He said it was probably his proudest victory, partly because the provisions of the Bill hadn't really registered with peers until he championed it. The whole scheme was "just too Orwellian for me", he said.

With the introduction of the House of Lords Reform Act in 2014, which allows life peers to resign from the House, Phillips finally resigned on 7 May 2015, the day of the General Election. During his second spell in the Lords, which lasted six years, he spoke on 844 occasions and cast 303 votes.[22]

He considered proposing an amendment to the Act allowing for anyone resigning their peerage to also lose their title. But other parliamentarians begged him not to, pointing out that all those peers who like their titles would choose not to resign. On that basis, he abandoned the amendment, but personally prefers to be addressed as Andrew and has described "Lord" as "such a vaunting title".

Views[]

Views on the decline of community[]

Phillips has often lamented the erosion of civic values and citizen responsibility, and warned about the growing culture of materialism and destruction of trust in society.

In 2007 he made a citizen's arrest on a boy who allegedly threw Phillips’s bike to the ground, after he told the boy and his friends they shouldn't cycle along a narrow path as it could be dangerous to parents with prams.[23]

In 2014 he delivered the Hinton Lecture for the National Council for Voluntary Organisations. It was titled "Whither the common good?" and in it he lamented the "disillusioned citizenry", "macho-money-lust" and "licensed greed and corruption" that have taken over society.[24]

At a Charity Finance Group event in 2012, he decried our "valueless society" and said the voluntary sector was its only hope.[25]

In one of his final days in the Lords, in March 2015, he asked the government to establish a Royal Commission to investigate threats to community life in the United Kingdom and recommend counter-measures.[26] The suggestion was not taken up.

Phillips has also denounced a similar decline in values in the law profession. At a seminar sponsored by the Gordon Cook Foundation in 2007, he recalled with dismay the removal of the 20-partner limit on law firms, the Law Society's abandonment of the no-advertising rule, the passing of the Limited Liability Partnership Act which allowed law firms to incorporate with limited liability, and the introduction of the Legal Services Bill which paved the way for firms to be owned and controlled by external shareholders. "In effect, we are de-professionalising ourselves, losing our autonomy and cohesion and further diluting our ethos," he said. And in an interview with The Times in 2012 about the opening up of law practices to private equity, he said the profession had sold its soul: “The law has become another tool for the rich and mighty that others can’t access."[27]

Views on Israel[]

Phillips has stated that he is a supporter of Israel, and offered to fight for Israel in the 1973 Arab–Israeli War. But visiting Israel, the West Bank and Gaza for the first time in 2001, and a number of times since, has altered his view. He believes Israel's controls on Gaza are contrary to international law and simple morality, and that international action on the Gaza situation is in the interests of Israel.[28] Phillips has called for economic and cultural sanctions on Israel.[29]

Jewish Chronicle blogs[clarification needed] have been critical of Phillips views, suggesting that he is being critical of Jews as well as of Israel.[30][31]

Family life[]

Andrew Phillips married Penelope Ann Bennett in 1968. They have a son, two daughters and five grandchildren. He lists among his recreational interests theatre, local history (especially of Suffolk), arts, architecture (especially parish churches), golf, walking and reading.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Lord Phillips of Sudbury". Bates Wells Braithwaite. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ames, Jonathan (31 May 2012). "Lord Phillips: law has become tool for rich". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ "Who We Are". Bates Wells Braithwaite. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ^ Forster-Heinzer, Sarah (2014), "Against All Odds", SensePublishers, pp. 1–8, doi:10.1007/978-94-6209-941-8_1, ISBN 9789462099418 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ "Andrew Phillips". IMDb. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ "Andrew Phillips | The Guardian". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ "Forster, Prof. Anthony William, (born 19 May 1964), Vice-Chancellor, University of Essex, since 2012", Who's Who, Oxford University Press, 1 December 2013, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.257441

- ^ "Brackenbury, Sir Henry Britten, (1866–8 March 1942), Vice-President, British Medical Association (Chairman of Council, 1927–34); Vice-President, late Chairman of Council, Tavistock Clinic; Vice-President, Association of Education Committees (President, 1914–18); Member, General Medical Council; Member of Advisory Committee to Ministry of Health", Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 1 December 2007, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u222935

- ^ "The Citizenship Foundation, registered charity no. 801360". Charity Commission.

- ^ "Our history". Young Citizens. Retrieved 30 April 2019.

- ^ Cook, Stephen. "Newsmaker: Legal eagle – Baron Phillips of Sudbury Liberal Democrat peer". thirdsector.co.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ Phillips, Lord Andrew. "'There can be no more reluctant Brexiteer than me'". East Anglian Daily Times. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- ^ "Harrison-Church, Prof. Ronald James, (26 July 1915 – 30 November 1998), Professor of Geography, University of London, at London School of Economics, 1964–77", Who Was Who, Oxford University Press, 1 December 2007, doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.u248870

- ^ https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/55210/page/8287

- ^ "Draft House of Lords Reform Bill – Hansard". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Constitutional Reform and Governance Bill – Hansard". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ Dines, Graham. "Call me Mr Phillips". East Anglian Daily Times. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Life Peerages (Disclaimer) Bill [HL] – Hansard". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Mr Andrew Phillips (Hansard)". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ King, Oliver; agencies (6 March 2006). "New ID cards defeat for government". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Peers threaten to scupper ID card link to passports". The Independent. 6 March 2006. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Lord Phillips of Sudbury – Contributions – Hansard". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Suffolk lord makes citizen's arrest". Ipswich Star. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "NCVO – Hinton lectures". ncvo.org.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Lord Phillips: 'Valueless' society needs the voluntary sector". civilsociety.co.uk. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Community Life – Hansard". Parliament of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ Ames, Jonathan (31 May 2012). "Lord Phillips: law has become tool for rich". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ Lord Phillips of Sudbury (3 December 2012). "Palestine: United Nations General Assembly Resolution". Lords Hansard. UK Parliament. 3 December 2012 : Column 507. Retrieved 20 November 2014.

- ^ Andrew Phillips (1 February 2010). "No relief for the Palestinians while Israel enjoys impunity". The Independent. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ Jessica Elgot (24 February 2011). "Jews? Many are just prejudiced". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ Jonathan Hoffman (3 November 2010). "Lord Phillips: "America is in the grip of the well-organised Jewish Lobby"". The Jewish Chronicle. Archived from the original on 6 November 2010.

External links[]

- Leigh Rayment’s Peerage Page

- Lib Dem peer loses bid to hand seat to ‘new blood’, The Guardian, 11 July 2006

- Just call me mister, says Lib-Dem peer, Daily Telegraph, 27 July 2006

- Lord Phillips of Sudbury recent appearances from TheyWorkForYou.com

- Lord Phillips of Sudbury, Bates, Wells & Braithwaite (archived 2013)

- 1939 births

- Living people

- People from Sudbury, Suffolk

- Liberal Democrats (UK) life peers

- Officers of the Order of the British Empire

- People educated at Culford School

- Chancellors of the University of Essex

- Alumni of Trinity Hall, Cambridge

- British solicitors

- Labour Party (UK) parliamentary candidates