Anglo-German Naval Agreement

| Notes between His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom and the German Government regarding the Limitation of Naval Armaments | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Naval limitation agreement |

| Signed | 18 June 1935 |

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

| Condition | Ratification by the Parliament of the United Kingdom and the German Reichstag. |

| Signatories | |

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement (AGNA) of 18 June 1935 was a naval agreement between the United Kingdom and Germany regulating the size of the Kriegsmarine in relation to the Royal Navy.

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement fixed a ratio whereby the total tonnage of the Kriegsmarine was to be 35% of the total tonnage of the Royal Navy on a permanent basis.[1] It was registered in League of Nations Treaty Series on 12 July 1935.[2] The agreement was denounced by Adolf Hitler on 28 April 1939.

The Anglo-German Naval Agreement was an ambitious attempt on the part of both the British and the Germans to reach better relations, but it ultimately foundered because of conflicting expectations between the two countries. For Germany, the Anglo-German Naval Agreement was intended to mark the beginning of an Anglo-German alliance against France and the Soviet Union,[3] whereas for Britain, the Anglo-German Naval Agreement was to be the beginning of a series of arms limitation agreements that were made to limit German expansionism. The Anglo-German Naval Agreement was controversial, both at the time and since, because the 35:100 tonnage ratio allowed Germany the right to build a Navy beyond the limits set by the Treaty of Versailles, and London had made the agreement without consulting the French or Italian governments.

Background[]

Part V of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles had imposed severe restrictions on the size and capacities of Germany's armed forces. Germany was allowed no submarines, no naval aviation, and only six obsolete pre-dreadnought battleships; the total naval forces allowed to the Germans were six armoured vessels of no more than 10,000 tons displacement, six light cruisers of no more than 6,000 tons displacement, twelve destroyers of no more than 800 tonnes displacement, and twelve torpedo boats.[4]

Through the interwar years German opinion had protested these restrictions as harsh and unjust, and demanded that either all the other states of Europe disarm to German levels, or Germany be allowed to rearm to the level of all the other European states. In Britain, where after 1919 guilt was felt over what was seen as the excessively harsh terms of Versailles, the German claim to "equality" in armaments often met with considerable sympathy. More importantly, every German government of the Weimar Republic was implacably opposed to the terms of Versailles, and given that Germany was potentially Europe's strongest power, from the British perspective it made sense to revise Versailles in Germany's favour as the best way of preserving the peace.[5] The British attitude was well summarised in a Foreign Office memo from 1935 that stated "... from the earliest years following the war it was our policy to eliminate those parts of the Peace Settlement which, as practical people, we knew to be unstable and indefensible".[6]

The change of regime in Germany in 1933 did cause alarm in London, but there was considerable uncertainty regarding Hitler's long-term intentions. The Secretary to the Committee of Imperial Defence (CID), Sir Maurice Hankey, visited Germany in August 1933, and wrote a report of his impressions of the "New Germany" that October. His report concluded with the words:

- "Are we still dealing with the Hitler of Mein Kampf, lulling his opponents to sleep with fair words to gain time to arm his people, and looking always to the day when he can throw off the mask and attack Poland? Or is it a new Hitler, who discovered the burden of responsible office, and wants to extricate himself, like many an earlier tyrant from the commitments of his irresponsible days? That is the riddle that has to be solved".[7]

This uncertainty over Hitler's ultimate intentions in foreign policy were to colour much of the British policy towards Germany until 1939.

[]

Equally important as one of the origins of the Treaty were the deep cuts made to the Royal Navy after the Washington Naval Conference of 1921–22 and the London Naval Conference of 1930.[8] The cuts imposed by the two conferences, combined with the effects of the Great Depression, caused the collapse of much of the British shipbuilding industry in the early 1930s.[9] That seriously hindered efforts at British naval rearmament later in the decade, leading the Admiralty to value treaties with quantitative and qualitative limitations on potential enemies as the best way of ensuring the royal Navy's sea supremacy.[10] Maiolo argues that it was actually of little importance whether potential enemies placed voluntary limitations on the size and scale of their navies.[11] In particular, Admiral Sir Ernle Chatfield, the First Sea Lord between 1933 and 1938, came to argue in favour of such treaties. They promised a standardised classification of different warships and discouraged technical innovations, which, under existing conditions, the Royal Navy could not always hope to match.[12] Chatfield especially wished for the Germans to do away with their Deutschland-class Panzerschiffe (known in the London press as "pocket battleships"), as such ships, embracing the characteristics of both battleships and cruisers, were dangerous to his vision of a world of regulated warship types and designs.[13] As part of the effort to do away with the Panzerschiffe, the British Admiralty stated in March 1932 and again in the spring of 1933 that Germany was entitled to "a moral right to some relaxation of the treaty [of Versailles]".[14]

World Disarmament Conference[]

In February 1932, the World Disarmament Conference opened in Geneva. Among the more hotly-debated issues at the conference was the German demand for Gleichberechtigung ("equality of armaments", abolishing Part V of Versailles) as opposed to the French demand for sécurité ("security"), maintaining Part V. The British attempted to play the "honest broker" and sought to seek a compromise between the French claim to sécurité and the German claim to Gleichberechtigung, which in practice meant backing the German claim to rearm beyond Part V, but not allowing the Germans to rearm enough to threaten France. Several of the British compromise proposals along these lines were rejected by both the French and German delegations as unacceptable.

In September 1932, Germany walked out of the conference, claiming it was impossible to achieve Gleichberechtigung. By this time, the electoral success of the Nazis had alarmed London, and it was felt unless the Weimar Republic could achieve some dramatic foreign policy success, Hitler might come to power. In order to lure the Germans back to Geneva, after several months of strong diplomatic pressure by London on Paris, in December 1932 all the other delegations voted for a British-sponsored resolution that would allow for the "theoretical equality of rights in a system which would provide security for all nations".[15][16] Germany agreed to return to the conference. Thus, before Hitler became Chancellor, it had been accepted that Germany could rearm beyond the limits set by Versailles, though the precise extent of German rearmament was still open to negotiation.

Adolf Hitler[]

During the 1920s, Hitler's thinking on foreign policy went through a dramatic change. At the beginning of his political career Hitler was hostile to the UK, considering it an enemy of the Reich. However, after the UK opposed the French occupation of the Ruhr in 1923, he came to rank the UK as a potential ally.[17] In Mein Kampf, and even more in its sequel, Zweites Buch, Hitler strongly criticised the pre-1914 German government for embarking on a naval and colonial challenge to the British Empire, and in Hitler's view, needlessly antagonizing the UK.[18] In Hitler's view, the UK was a fellow "Aryan" power, whose friendship could be won by a German "renunciation" of naval and colonial ambitions against the UK.[18] In return for such a "renunciation", Hitler expected an Anglo-German alliance directed at France and the Soviet Union, and the UK's support for the German efforts to acquire Lebensraum in Eastern Europe. As the first step towards the Anglo-German alliance, Hitler had written in Mein Kampf of his intention to seek a "sea pact", by which Germany would "renounce" any naval challenge against the UK.[19]

In January 1933, Hitler became the German chancellor. The new government in Germany had inherited a strong negotiating position at Geneva from the previous government of General Kurt von Schleicher. The German strategy was to make idealistic offers of limited rearmament, out of the expectation that all such offers would be rejected by the French, allowing Germany to go on ultimately with the maximum rearmament. The ultra-nationalism of the Nazi regime had alarmed the French, who put the most minimal possible interpretation of German "theoretical equality" in armaments, and thereby played into the German strategy. In October 1933, the Germans again walked out of the conference, stating that everyone else should either disarm to the Versailles level, or allow Germany to rearm beyond Versailles.[14] Though the Germans never had any serious interest in accepting any of the UK's various compromise proposals, in London, the German walk-out was widely, if erroneously, blamed on French "intransigence". The UK Government was left with the conviction that, in the future, opportunities for arms limitation talks with the Germans should not be lost because of French "intransigence". Subsequent offers by the UK to arrange for the German return to the World Disarmament Conference were sabotaged by the Germans putting forward proposals that were meant to appeal to the UK while being unacceptable to the French. On 17 April 1934, the last such effort ended with the French Foreign Minister Louis Barthou's rejection of the latest German offer as unacceptable in the so-called "Barthou note" which ended French participation in the Conference while declaring that France would look after its own security in whatever way was necessary. At the same time, Admiral Erich Raeder of the Reichsmarine persuaded Hitler of the advantages of ordering two more Panzerschiffe, and in 1933 advised the Chancellor that Germany would be best off by 1948 with a fleet of three aircraft carriers, 18 cruisers, eight Panzerschiffe, 48 destroyers and 74 U-boats.[20] Admiral Raeder argued to Hitler that Germany needed naval parity with France as a minimum goal, whereas Hitler from April 1933 onwards, expressed a desire for a Reichsmarine of 33.3% of the total tonnage of the Royal Navy.[21]

In November 1934, the Germans formally informed the UK of their wish to reach a treaty with the UK, under which the Reichsmarine would be allowed to grow until the size of 35% of the Royal Navy. The figure was raised because the phrase of a German goal of "one third of the Royal Navy except in cruisers, destroyers, and submarines" did not sound quite right in speeches.[21] Admiral Raeder felt that the 35:100 ratio was unacceptable towards Germany, but was overruled by Hitler who insisted on the 35:100 ratio.[22] Aware of the German desire to expand their Navy beyond Versailles, Admiral Chatfield repeatedly advised it would be best to reach a naval treaty with Germany so as to regulate the future size and scale of the German navy.[23] Though the Admiralty described the idea of a 35:100 tonnage ratio between London and Berlin as "the highest that we could accept for any European power", it advised the government that the earliest Germany could build a Navy to that size was 1942, and that though they would prefer a smaller tonnage ratio than 35:100, a 35:100 ratio was nonetheless acceptable.[24] In December 1934, a study done by Captain Edward King, Director of the Royal Navy's Plans Division suggested that the most dangerous form a future German Navy might take from the UK's perspective would be a Kreuzerkrieg (Cruiser war) fleet.[25] Captain King argued that guerre-de-course German fleet of Panzerschiffe, cruisers, and U-boats operating in task forces would be dangerous for the Royal Navy, and that a German "balanced fleet" that would be a mirror image of the Royal Navy would be the least dangerous form the German Navy could take.[26] A German "balanced fleet" would have proportionally the same number of battleships, cruisers, destroyers, etc. that the UK's fleet possessed, and from the UK's point of view, this would be in the event of war, the easiest German fleet to defeat.[26]

U-boat construction[]

Though every government of the Weimar Republic had violated Part V of Versailles, in 1933 and 1934, the Nazi government had become more flagrant and open in violating Part V. In 1933, the Germans started to build their first U-boats since World War I, and in April 1935, launched their first U-boats.[27] On 25 April 1935, the UK's naval attaché to Germany, Captain Gerard Muirhead-Gould was officially informed by Captain Leopold Bürkner of the Reichsmarine that Germany had laid down twelve 250 ton U-boats at Kiel.[28] On 29 April 1935, the Foreign Secretary Sir John Simon informed the British House of Commons that Germany was now building U-boats.[28] On 2 May 1935, the Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald told the House of his government's intention to reach a naval pact to regulate the future growth of the German Navy.[28]

In a more general sense, because of the UK's championing of German "theoretical equality" at the World Disarmament Conference, London was in a weak moral position to oppose the German violations. The German response to the UK's complaints about violations of Part V were that they were merely unilaterally exercising rights the UK's delegation at Geneva were prepared to concede to the Reich. In March 1934, a British Foreign Office memo stated "Part V of the Treaty of Versailles... is, for practical purposes, dead, and it would become a putrefying corpse which, if left unburied, would soon poison the political atmosphere of Europe. Moreover, if there is to be a funeral, it is clearly better to arrange it while Hitler is still in a mood to pay the undertakers for their services".[29]

In December 1934, a secret Cabinet committee met to discuss the situation caused by German rearmament. The UK Foreign Secretary Sir John Simon stated at one of the committee's meetings that "If the alternative to legalizing German rearmament was to prevent it, there would be everything to be said, for not legalizing it".[30] But since London had already rejected the idea of a war to end German rearmament, the UK Government chose a diplomatic strategy that would allow abolition of Part V in exchange for German return to both the League of Nations, and the World Disarmament Conference.[30] At the same meeting, Simon stated "Germany would prefer, it appears, to be ‘made an honest woman'; but if she is left too long to indulge in illegitimate practices and to find by experience that she does not suffer for it, this laudable ambition may wear off".[31] In January 1935, Simon wrote to George V that "The practical choice is between a Germany which continues to rearm without any regulation or agreement and a Germany which, through getting a recognition of its rights and some modifications of the Peace Treaties enters into the comity of nations and contributes in this or other ways to European stability. As between these two courses, there can be no doubt which is the wiser".[32] In February 1935, a summit in London between the French Premier Pierre Laval and UK Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald led to an Anglo-French communiqué issued in London that proposed talks with the Germans on arms limitation, an air pact, and security pacts for Eastern Europe and the nations along the Danube.[33]

Talks[]

In early March 1935, talks intended to discuss the scale and extent of German rearmament in Berlin between Hitler and Simon were postponed when Hitler took offence at a UK Government White Paper that justified a higher defence budget under the grounds that Germany was violating the Versailles Treaty, and he claimed to have contracted a "cold". In the interval between Hitler "recovering" and Simon's visit, the German government took the chance for formally rejecting all the clauses of Versailles relating to disarmament on the land and air. In the 1930s, the UK Government was obsessed with the idea of a German bombing attack destroying London and so placed a great deal of value on reaching an air pact outlawing bombing.[34] The idea of a naval agreement was felt to be a useful stepping stone to an air pact.[34] On 26 March 1935, during one of his meetings with Simon, and his deputy Anthony Eden, Hitler stated his intention to reject the naval disarmament section of Versailles but was prepared to discuss a treaty regulating the scale of German naval rearmament.[35] On 21 May 1935, Hitler in a speech in Berlin formally offered to discuss a treaty offering a German Navy that was to operate forever on a 35:100 naval ratio.[36] During his "peace speech" of 21 May, Hitler disavowed any intention of engaging in a pre-1914 style naval race with the UK, and he stated: "The German Reich government recognises of itself the overwhelming importance for existence and thereby the justification of dominance at sea to protect the British Empire, just as, on the other hand, we are determined to do everything necessary in protection of our own continental existence and freedom".[22] For Hitler, his speech illustrated the quid pro quo of an Anglo-German alliance, the UK's acceptance of German mastery of Continental Europe in exchange for German acceptance of the UK's mastery over the seas.[22]

On 22 May 1935, the British Cabinet voted for formally taking up Hitler's offers of 21 May as soon as possible.[36] Sir Eric Phipps, the UK's ambassador in Berlin, advised London that no chance at a naval agreement with Germany should be lost "owing to French shortsightedness".[36] Chatfield informed the Cabinet that it was most unwise to "oppose [Hitler's] offer, but what the reactions of the French will be to it are more uncertain and its reaction on our own battleship replacement still more so".[36]

On 27 March 1935, Hitler had appointed Joachim von Ribbentrop to head the German delegation to negotiate any naval treaty.[37] Von Ribbentrop served as both Hitler's Extraordinary Ambassador–Plenipotentiary at Large (making part of the Auswärtiges Amt, the German Foreign Office) and as the chief of a Nazi Party organization named the Dienststelle Ribbentrop that competed with the Auswärtiges Amt. Baron Konstantin von Neurath, the German Foreign Minister, was first opposed to this arrangement, but he changed his mind when he decided that the UK would never accept the 35:100 ratio; having Ribbentrop head the mission was the best way to discredit his rival.[38]

On 2 June 1935, Ribbentrop arrived in London. The talks began on Tuesday, 4 June 1935, at the Admiralty office with Ribbentrop heading the German delegation and Simon the UK's delegation.[39] Ribbentrop, who was determined to succeed at his mission no matter what, began his talks by stating the UK could either accept the 35:100 ratio as "fixed and unalterable" by the weekend, or the German delegation would go home, and the Germans would build their navy up to any size they wished.[36][40] Simon was visibly angry with Ribbentrop's behaviour: "It is not usual to make such conditions at the beginning of negotiations". Simon walked out of the talks.[40] On 5 June 1935, a change of opinion came over the UK's delegation. In a report to the British Cabinet, it was "definitely of the opinion that, in our own interest, we should accept this offer of Herr Hitler's while it is still open.... If we now refuse to accept the offer for the purposes of these discussions, Herr Hitler will withdraw the offer and Germany will seek to build to a higher level than 35 per cent.... Having regard to past history and to Germany's known capacity to become a serious naval rival of this country, we may have cause to regret it if we fail to take this chance...".[41] Also, on 5 June, during talks between Sir Robert Craigie, the British Foreign Office's naval expert and chief of the Foreign Office's American Department, and Ribbentrop's deputy, Admiral Karlgeorg Schuster, the Germans conceded that the 35:100 ratio would be expressed in ship tonnage, the Germans building their tonnage up to whatever the UK's tonnage was in various warship categories.[39] On the afternoon of that same day, the British Cabinet voted to accept the 35:100 ratio, and Ribbentrop was informed of the Cabinet's acceptance in the evening.[41]

During the next two weeks, talks continued in London on various technical issues, mostly relating to how the tonnage ratios would be calculated in the various warship categories.[42] Ribbentrop was desperate for success and so agreed to almost all the UK's demands.[42] On 18 June 1935, the agreement was signed in London by Ribbentrop, and the new UK Foreign Secretary, Sir Samuel Hoare. Hitler called 18 June 1935, the day of the signing, "the happiest day of his life", as he believed that it marked the beginning of an Anglo-German alliance.[43][44]

Text[]

"Exchange of Notes between His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom and the German Government regarding the Limitation of Naval Armaments-London, 18 June 1935.

(1)

Sir Samuel Hoare to Herr von Ribbentrop Your Excellency, Foreign Office, June 18, 1935

During the last few days the representatives of the German Government and His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom have been engaged in conversations, the primary purpose of which has been to prepare the way for the holding of a general conference on the subject of the limitation of naval armaments. I have now much pleasure in notifying your Excellency of the formal acceptance by His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom of the proposal of the German Government discussed at those conversations that the future strength of the German navy in relation to the aggregate naval strength of the Members of the British Commonwealth of Nations should be in the proportion of 35:100. His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom regard this proposal as a contribution of the greatest importance to the cause of future naval limitation. They further believe that the agreement which they have now reached with the German government, and which they regard as a permanent and definite agreement as from to-day between the two Governments, will facilitate the conclusion of a general agreement on the subject of naval limitation between all the naval Powers of the world.

2. His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom also agree with the explanations which were furnished by the German representatives in the course of the recent discussions in London as the method of application of this principle. These explanations may be summarised as follows:-

(a) The ratio of 35:100 is to be a permanent relationship, i.e. the total tonnage of the German fleet shall never exceed a percentage of 35 of the aggregate tonnage of the naval forces, as defined by treaty, of the Members of the British Commonwealth of Nations, or, if there should in the future, be no treaty limitations of the Members of the British Commonwealth of Nations.

(b) If any future general treaty of naval limitation should not adopt the method of limitation by agreed ratios between the fleets of different Powers, the German Government will not insist on the incorporation of the ratio mentioned in the preceding sub-paragraph in such future general treaty, provided that the method therein adopted for the future limitation of naval armaments is such as to give Germany full guarantees that this ratio can be maintained.

(c) Germany will adhere to the ratio 35:100 in all circumstances, e.g. the ratio will not be affected by the construction of other Powers. If the general equilibrium of naval armaments, as normally maintained in the past, should be violently upset by any abnormal and exceptional construction by other Powers, the German Government reserve the right to invite His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom to examine the new situation thus created.

(d)The German Government favour, the matter of limitation of naval armaments, that system which divides naval vessels into categories, fixing the maximum tonnage and/or armament for vessels in each category, and allocates the tonnage to be allowed to each Power by categories of vessels. Consequently, in principle, and subject to (f) below, the German Government are prepared to apply the 35 per cent. ratio to the tonnage of each category of vessel to be maintained, and to make any variation of this ratio in a particular category or categories dependent on the arrangements to this end that may be arrived at in a future general treaty on naval limitation, such arrangements being based on the principle that any increase in one category would be compensated for by a corresponding reduction in others. If no general treaty on naval limitation should be concluded, or if the future general treaty should not contain provision creating limitation by categories, the manner and degree in which the German Government will have the right to vary the 35 percent. ratio in one or more categories will be a matter for settlement by agreement between the German Government and His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom, in the light of the naval situation then existing.

(e) If, and for so long as other important naval Powers retain a single category for cruisers and destroyers, Germany shall enjoy the right to have a single category for these two classes of vessels, although she would prefer to see these classes in two categories.

(f) In the matter of submarines, however, Germany, while not exceeding the ratio of 35:100 in respect of total tonnage, shall have the right to possess a submarine tonnage equal to the total submarine tonnage possessed by the Members of the British Commonwealth of Nations. The German Government, however, undertake that, except in the circumstances indicated in the immediately following sentence, Germany's submarine tonnage shall not exceed 45 percent. of the total of that possessed by the Members of the British Commonwealth of Nations. The German Government reserve the right, in the event of a situation arising, which in their opinion, makes it necessary for Germany to avail herself of her right to a percentage of submarine tonnage exceeding the 45 per cent. above mentioned, to give notice this effect to His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom, and agree that the matter shall be the subject of friendly discussion before the German Government exercise that right.

(g) Since it is highly improbable that the calculation of the 35 per cent. ratio should give for each category of vessels tonnage figures exactly divisible by the maximum individual tonnage permitted for ships in that category, it may be necessary that adjustments should be make in order that Germany shall not be debarred from utilising her tonnage to the full. It has consequently been agreed that the German Government and His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom will settle by common accord what adjustments are necessary for this purpose, and it will be understood that this procedure shall not result in any substantial or permanent departure from the ratio 35:100 in respect of total strengths.

3. With reference to sub-paragraph (c) of the explanations set out above, I have the honour to inform you that His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom have taken note of the reservation and recognise in the right therein set out, on the understanding that the 35:100 ratio will be maintained in default of agreement to the contrary between the two Governments.

4. I have the honour to request your Excellency to inform me that the German Government agrees that the proposal of the German Government has been correctly set out in the preceding paragraphs of this note.

I have. & c.

SAMUEL HOARE

(2)

(Translation)

Herr von Ribbentrop to Sir Samuel Hoare

Your Excellency, London, June 18, 1935

I have the honour to acknowledge the receipt of your Excellency's note of to-day's date, in which you were so good as to communicate to me on behalf of His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom the following:-

(Here follows a German translation of paragraphs 1 to 3 of No. 1.)

I have the honour to confirm to your Excellency that the proposal of the German Government is correctly set forth in the foregoing note, and I note with pleasure that His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom accept this proposal.

The German Government, for their part, are also of the opinion that the agreement at which they have now arrived with His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom, and which they regard as a permanent and definite agreement with effect from to-day between the two Governments, will facilitate the conclusion of a general agreement on this question between all the naval Powers of the world.

I have, & c.

JOACHIM VON RIBBENTROP,

Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Germany".[45]

French reaction[]

The Naval Pact was signed in London on 18 June 1935 without the UK Government consulting with France and Italy, or, later, informing them of the secret agreements which stipulated that the Germans could build in certain categories more powerful warships than any of the three Western nations then possessed. The French regarded this as treachery. They saw it as a further appeasement of Hitler, whose appetite grew on concessions. Also, they resented that the UK's agreement had for private gain further weakened the peace treaty, thus adding to the growing overall military power of Germany. The French contended that the UK had no legal right to absolve Germany from respecting the naval clauses of the Versailles Treaty.[46]

As an additional insult for France, the Naval Pact was signed on the 120th anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo, at which British and Prussian troops defeated the French army of Napoleon.

Impact[]

Because of the lengthy period needed to construct warships and the short duration of the agreement its impact was limited. It was estimated by both German and British naval experts that the earliest year that Germany could reach the 35% limit was 1942.[47] In practice, lack of shipbuilding space, design problems, shortages of skilled workers, and the scarcity of foreign exchange to purchase necessary raw materials slowed the rebuilding of the German Navy. A lack of steel and non-ferrous metals caused by the Kriegsmarine being third in terms of German rearmament priorities, behind the Heer and the Luftwaffe, led to the Kriegsmarine (as the German Navy had been renamed in 1935) being still far from the 35% limit when Hitler denounced the agreement in 1939.[48]

The requirement for the Kriegsmarine to divide its 35% tonnage ratio by warship categories had the effect of forcing the Germans to build a symmetrical "balanced fleet" shipbuilding program that reflected the UK's priorities.[25] Since the Royal Navy's leadership thought that the "balanced fleet" would be the easiest German fleet to defeat and a German guerre-de-course fleet the most dangerous, the agreement brought the UK considerable strategic benefits.[49] Above all, since the Royal Navy did not build "pocket battleships", Chatfield valued the end of the Panzerschiff building.[49]

When the Kriegsmarine began planning for a war with the UK in May 1938, the Kriegsmarine's senior operations officer, Commander Hellmuth Heye, concluded the best strategy for the Kriegsmarine was a Kreuzerkrieg fleet of U-boats, light cruisers and Panzerschiff operating in tandem.[50] He was critical of the existing building priorities dictated by the agreement since there was no realistic possibility of a German "balanced fleet" defeating the Royal Navy.[50] In response, senior German naval officers started to advocate a switch to a Kreuzerkrieg type fleet that would pursue a guerre-de-course strategy of attacking the British Merchant Marine, but they were overruled by Hitler, who insisted on the prestige of Germany building a "balanced fleet". Such a fleet would attempt a Mahanian strategy of winning maritime supremacy by a decisive battle with the Royal Navy in the North Sea.[51] Historians such as Joseph Maiolo, Geoffrey Till and the authors of the Kriegsmarine Official History have agreed with Chatfield's contention that a Kreuzerkrieg fleet offered Germany the best chance for damaging the UK's power and that the UK benefited strategically by ensuring that such a fleet was not built in the 1930s.[52]

In the field of Anglo-German relations, the agreement had considerable importance. The UK expressed hope, as Craigie informed Ribbentrop, that it "was designed to facilitate further agreements within a wider framework and there was no further thought behind it".[3] In addition, the UK viewed it as a "yardstick" for measuring German intentions towards the UK.[53] Hitler regarded it as marking the beginning of an Anglo-German alliance and was much annoyed when this did not result.[54]

By 1937, Hitler started to increase both the sums of Reichmarks and raw materials to the Kriegsmarine, reflecting the increasing conviction that if war came, the UK would be an enemy, not an ally, of Germany.[55] In December 1937, Hitler ordered the Kriegsmarine to start laying down six 16-inch gun battleships.[55] At his meeting with Lord Halifax in November 1937, Hitler stated that the agreement was the only item in the field of Anglo-German relations that had not been "wrecked".[56]

By 1938, the only use the Germans had for the agreement was to threaten to renounce it as a way of pressuring London to accept Continental Europe as Germany's rightful sphere of influence.[57] At a meeting on 16 April 1938 between Sir Nevile Henderson, the UK's ambassador to Germany, and Hermann Göring, the latter stated it had never been valued in England, and he bitterly regretted that Herr Hitler had ever consented to it at the time without getting anything in exchange. It had been a mistake, but Germany was nevertheless not going to remain in a state of inferiority in this respect vis-à-vis a hostile UK, and would build up to a 100 per cent basis.[58]

In response to Göring's statement, a joint Admiralty-Foreign Office note was sent to Henderson to inform him that he should inform the Germans:

"Field Marshal Göring's threat that in certain circumstances Germany might, presumably after denouncing the Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935, proceed to build up to 100% of the British fleet is clearly bluff [emphasis in the original]. In view of the great existing disparities in the size of the two navies this threat could only be executed if British construction were to remain stationary over a considerable period of years whilst German tonnage was built up to it. This would not occur. Although Germany is doubtless capable of realizing the 35% figure by 1942 if she so desires, or even appreciably earlier, it seems unlikely (considering her difficulties in connection with raw material, foreign exchange and the necessity of giving priority to her vast rearmament on land and in the air, and considering our own big programme) that she would appreciably exceed that figure during the next few years. This is not to say we have not every interest in avoiding a denunciation of the Anglo-German Agreement of 1935, which would create a present state of uncertainty as to Germany's intentions and the ultimate threat of an attempt at parity with our Navy, which must be regarded as potentially dangerous given that Germany has been credited with a capacity for naval construction little inferior to our own. Indeed, so important is the Naval Agreement to His Majesty's Government that it is difficult to conceive that any general understanding between Great Britain and Germany, such as General Göring is believed to desire, would any longer be possible were the German Government to denounce the Naval Agreement. In fact, a reaffirmation of the latter in all probability have to figure as part of such a general understanding.

The German Navy was for Germany mainly an instrument for putting political pressure on Britain. Before the war, Germany would have been willing to cease or moderate its naval competition with Britain but only in return for a promise of its neutrality in any European conflict. Hitler attempted the same thing by different methods, but, like other German politicians, he saw only one side of the picture. It is clear from his writings that he was enormously impressed with the part played by the prewar naval rivalry in creating bad relations between the two countries. Thus he argued that the removal of this rivalry was all that was necessary to obtain good relations. By making a free gift of an absence of naval competition, he hoped that relations between the two countries would be so improved that Britain should not, in fact, find it necessary to interfere with Germany's continental policy.

He overlooked, like other German politicians, that Britain is bound to react not only against danger from any purely-naval rival, but also against dominance of Europe by any aggressive military power, particularly if that power is in a position to threaten the Low Countries and the Channel ports. British complaisance could never be purchased by trading one of the factors against the other, and any country that attempted so would be bound to create disappointment and disillusion, as Germany did.[59]

Munich agreement and denunciation[]

At the conference in Munich that led to the Munich Agreement in September 1938, Hitler informed Neville Chamberlain that if the UK's policy was "to make it clear in certain circumstances" that the UK might be intervening in a mainland European war, the political preconditions for the agreement no longer existed, and Germany should denounce it. This led to Chamberlain including mention of it in the Anglo-German Declaration of 30 September 1938.[60]

By the late 1930s, Hitler's disillusionment with the UK's led to German foreign policy taking increasing anti-UK course.[61] An important sign of Hitler's changed perceptions about the UK was his decision in January 1939 to give first priority to the Kriegsmarine in allocations of money, skilled workers and raw materials and to launch Plan Z to build a colossal Kriegsmarine of 10 battleships, 16 "pocket battleships", 8 aircraft carriers, 5 heavy cruisers, 36 light cruisers and 249 U-boats by 1944 purposed to crush the Royal Navy.[62] Since the fleet envisioned in the Z Plan was considerably larger than allowed by the 35:100 ratio in the agreement, it was inevitable that Germany would renounce it. Over the winter of 1938–39, it became clearer to London that the Germans no longer intended to abide by the agreement, which played a role in straining Anglo-German relations.[63] Reports received in October 1938 that the Germans were considering denouncing the agreement were used by Halifax in Cabinet discussions for the need for a tougher policy with the Reich.[64] The German statement of 9 December 1938 of intending to build to 100% ratio allowed in submarines by the agreement and to the limits in heavy cruisers led to a speech by Chamberlain before the correspondents of the German News Agency in London that warned of the "futility of ambition, if ambition leads to the desire for domination".[65]

At the same time, Halifax informed Herbert von Dirksen, the German ambassador to the UK, that his government viewed the talks to discuss the details of the German building escalation as a test case for German sincerity.[66] When the talks began in Berlin on 30 December 1938, the Germans took an obdurate approach, leading London to conclude that the Germans did not wish for the talks to succeed.[67]

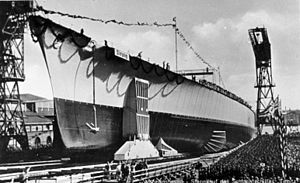

In response to the UK's "guarantee" of Poland of 31 March 1939, Hitler, enraged by the UK's move proclaimed "I shall brew them a devil's drink".[68] In a speech in Wilhelmshaven for the launch of the battleship Tirpitz, Hitler threatened to denounce the agreement if the UK persisted with its "encirclement" policy, as represented by the "guarantee" of Polish independence.[68] On 28 April 1939, Hitler denounced the AGNA.[68] To provide an excuse for its denunciation of and to prevent the emergence of a new naval treaty, the Germans began refusing to share information about their shipbuilding, leaving the UK with the choice of either accepting the unilateral German move or rejecting it, thus providing the Germans with the excuse to denounce the treaty.[69]

At a Cabinet meeting on 3 May 1939, the First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Stanhope, stated that "at the present time Germany was building ships as fast as she could but that she would not be able to exceed the 35 per cent ratio before 1942 or 1943".[69] Chatfield, now Minister for the Co-ordination of Defence, commented that Hitler had "persuaded himself" that the UK had provided the Reich with a "free hand" in Eastern Europe in exchange for the agreement.[69] Chamberlain stated that the UK had never given such an understanding to Germany, and he commented that he first learned of Hitler's belief in such an implied bargain during his meeting with the Führer at the Berchtesgaden summit in September 1938.[69] In a later paper to the Cabinet, Chatfield stated "that we might say that we now understood Herr Hitler had in 1935 thought that we had given him a free hand in Eastern and Central Europe in return for his acceptance of the 100:35 ratio, but that as we could not accept the correctness of this view it might be better that the 1935 arrangements should be abrogated".[70]

In the end, the UK's reply to the German move was a diplomatic note, strongly disputing the German claim that the UK was attempting to "encircle" Germany with hostile alliances.[70] The German denunciation and reports of increased German shipbuilding in June 1939 caused by the Z Plan played a significant part in persuading the Chamberlain government of the need to "contain" Germany by building a "Peace front" of states in both Western and Eastern Europe and raised the perception in the Chamberlain government in 1939 that German policies were a threat to the UK.[71]

See also[]

- Appeasement

- Stresa front

- Events preceding World War II in Europe

Notes[]

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 35–36.

- ^ League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 161, pp. 10–20.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maiolo 1998, p. 37.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, p. 20.

- ^ Gilbert 1966, p. 57.

- ^ Medlicott 1969, p. 3.

- ^ Document 181 C10156/2293/118 "Notes by Sir Maurice Hankey on Hitler's External Policy in Theory and Practice October 24, 1933" from British Documents on Foreign Affairs Germany 1933 page 339.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 11–12, 14–15.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 15–16, 21.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maiolo 1998, p. 21.

- ^ Weinberg 1970, p. 40.

- ^ Doerr 1998, p. 128.

- ^ Jäckel 1981, p. 31.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jäckel 1981, p. 20.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, p. 22.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, p. 23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maiolo 1998, p. 24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kershaw 1998, p. 556.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, p. 26.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 26–18.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maiolo 1998, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maiolo 1998, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Maiolo 1998, p. 33.

- ^ Medlicott 1969, p. 9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dutton 1992, p. 187.

- ^ Dutton 1992, p. 188.

- ^ Haraszti 1974, p. 22.

- ^ Messerschmidt 1990, p. 613.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maiolo 1998, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Weinberg 1970, p. 212.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Maiolo 1998, p. 34.

- ^ Bloch 1992, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Bloch 1992, p. 69.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maiolo 1998, p. 35.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bloch 1992, p. 72.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bloch 1992, p. 73.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bloch 1992, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Kershaw 1998, p. 558.

- ^ Hildebrand 1973, p. 39.

- ^ Document 121 [A5462/22/45] from British Documents on Foreign Affairs Series 5, Volume 46 Germany 1935 edited by Jeremy Noakes, London: Public Record Office, 1994 pages 181–183.

- ^ Shirer 1969, pp. 249–250.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 57–59.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, p. 60.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maiolo 1998, pp. 68–70.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maiolo 1998, p. 71.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, p. 73.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, p. 184.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 48, 190.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maiolo 1998, pp. 48, 138.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, p. 155.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 155–156.

- ^ Haraszti 1974, p. 245.

- ^ Haraszti 1974, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, p. 156.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 70–71, 154–155.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 74, 164–165.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, p. 165.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, p. 169.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, p. 170.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Maiolo 1998, p. 178.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Maiolo 1998, p. 179.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Maiolo 1998, p. 181.

- ^ Maiolo 1998, pp. 180–181, 184.

References[]

- Bloch, Michael (1992). Ribbentrop. New York: Crown Publishers Inc.

- Doerr, Paul W. (1998). British Foreign Policy, 1919-1939. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0719046728.

- Dutton, David (1992). Simon A Political Biography of Sir John Simon. London: Aurum Press.

- Gilbert, Martin (1966). The Roots of Appeasement. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- Hall III, Hines H. "The Foreign Policy-Making Process in Britain, 1934-1935, and the Origins of the Anglo-German Naval Agreement" Historical Journal (1976) 19#2 pp. 477–499 online

- Haraszti, Eva (1974). Treaty-Breakers or "Realpolitiker"? The Anglo-German Naval Agreement of June 1935. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado.

- Hildebrand, Klaus (1973). The Foreign Policy of the Third Reich. London: Batsford.

- Kershaw, Sir Ian (1998). Hitler 1889–1936: Hubris. New York: W.W. Norton.

- Jäckel, Eberhard (1981). Hitler's World View A Blueprint for Power. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Maiolo, Joseph (1998). The Royal Navy and Nazi Germany, 1933–39 A Study in Appeasement and the Origins of the Second World War. London: Macmillan Press. ISBN 0-312-21456-1.

- Medlicott, W. N. (1969). Britain and Germany: The Search For Agreement 1930–1937. London: Athlone Press.

- Messerschmidt, Manfred (1990). "Foreign Policy and Preparation for War". Germany and the Second World War the Build-up of German Aggression. Oxford: Clarendon Press. I: 541–718.

- Shirer, William (1969). The Collapse of the Third Republic: An Inquiry into the Fall of France in 1940. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Watt, D.C. (1956). "The Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935: An Interim Judgement". Journal of Modern History. 28 (28#2): 155–175. doi:10.1086/237885. JSTOR 1872538. S2CID 154892871.

- Weinberg, Gerhard (1970). The Foreign Policy of Hitler's Germany Diplomatic Revolution in Europe 1933-36. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Full Text of The Anglo-German Naval Agreement of 1935 Naval Weapons of the World

- Bilateral treaties of the United Kingdom

- Politics of World War II

- Military history of Germany during World War II

- Military history of the United Kingdom during World War II

- Naval history of Germany

- History of the Royal Navy

- 1935 in the United Kingdom

- Germany–United Kingdom military relations

- Arms control treaties

- Interwar-period treaties

- Treaties concluded in 1935

- Treaties of Nazi Germany

- Naval treaties

- 1935 in British politics