Anti-monuments in Mexico

In Mexico, anti-monuments (Spanish: antimonumentos) are installed and traditionally placed during popular protests. They are installed to recall a tragic event or to maintain the claim for justice to which governments have failed to provide a satisfactory response in the eyes of the complainant.[1]

Many of these are erected for issues related to forced disappearances, massacres, femicides and other forms of violence against women, or any other act of violence.

Concept[]

The term anti-monument finds its genealogy in the reflections of James E. Young. After World War II, Young looked at "those devices of memory that do not seek to glorify national glory but to do a living memory work through the experiences of the victims", in contrast to the traditional monuments that exalted nationalist heroism.[1] Young used the term counter-monument to refer to this type of expression. He exemplified this with the Monument Against Fascism (Hamburg, 1986) by Jochen Gerz and Esther Shalev-Gerz. It consisted of a twelve-meter-high stele on which passers-by could write their names or any kind of reflection, so that little by little the stele would be hidden to "embody the absence of fascism".[1]

However, according to this classification, it is difficult to locate their origin, since there are many actions that could be classified as anti-monuments, at least since 1977.[1] In Latin America, anti-monuments emerged as a way of dealing through the arts with "the violence of the State, as in the cases of Nazism and Latin American dictatorships".[2]

In Mexico, anti-monuments have emerged as a rejection of the state. If traditional monuments are usually installed by the state to last and represent official positions, the anti-monument has the opposite function which "does not imply a denial of the importance of monuments".[3] That is, it tries to remember those victims who did not achieve justice so that "their cases do not fall into oblivion".[4] Thus, according to anthropologist Alfonso Díaz Tovar, the anti-monuments arise in this way to "deconstruct" the "official positions through an appropriation of public space".[4]

They have also been interpreted as "a new way of dealing with the new role of memory".[1]

Cause and implications[]

Mexico is a country where nine out of ten reported crimes are left unpunished.[1][4] As a result, anti-monuments have emerged as a way to remember the victims and prevent their cases from falling into oblivion.[4] For Rosa Salazar, Human Rights, Communication and ICT Laboratory coordinator, anti-monuments have a function similar to that of memorials.[5]

Anti-monuments leave behind the idea that aesthetic objects "were only judged by their beauty, according to a given artistic canon". Apart from their aesthetic appearance, anti-monuments are "artifacts charged with affection" that, with their subversive activities in the public space, tend to reinstate its communitarian sense.[1] For Eunice Hernández, cultural gestor, their location is key to prevent oblivion, since those spaces are emblematic and represent a hegemonic power.[6]

Government position[]

Anti-monuments are rarely removed by the authorities. Although not removing them can affect the image of the government, removing them would imply that they have no interest in resolving the cause of their placement. After being installed, several sit-in groups remain in the area watching over the anti-monuments to prevent the authorities from removing them.[7]

In some instances, some governments have installed their own anti-monuments and in other cases have tried to dialogue with the protesters to decide where or how they should be installed. For philosopher Irene Tello Arista, these actions represent an absence of political commitment to change the situation that originated them.[8]

Antimonumenta[]

The antimonumenta is a type of anti-monument erected to demand justice for the victims of gender violence and femicides in the country.[8]

The first antimonumenta was erected on 8 March 2019, the date commemorating International Women's Day. It was installed on Juárez Avenue, in front of the Palace of Fine Arts in downtown Mexico City during the annual march of women protesting against gender violence. Since then, similar monuments have been installed throughout the country.[9]

The Antimonumenta represents the symbol of the feminist struggle, which is based on the symbol of Venus with a raised fist in the center. The antimonumentas of Mexico City and Guadalajara, for example, are purple. The color represents the history of the feminist struggle: "loyalty, constancy towards a purpose, unwavering firmness towards a cause".[10]

List of anti-monuments[]

| Picture | Name[a] | In memory of | Description | State | Location | Date of installment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

The students that were abducted during the 2014 Iguala mass kidnapping. | The anti-monument features a "Plus 43" and a "Because they were taken alive, we want them alive!" slogan in reference to the 43 students that were kidnapped as they were traveling to commemorate the anniversary of the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre. Six other students were killed.[11] In 2018, a concrete turtle whose shell contains 43 little turtles and whose limbs bear the names of the students, was built in front of the anti-monument.[12] | Mexico City | In front of the Excélsior Building, Paseo de la Reforma Avenue, Colonia Centro | 26 April 2015 | |

|

25 September 2018 | |||||

|

The 49 children who died during the 2009 Hermosillo daycare center fire. | The anti-monument has a 49 and the letters "ABC" in reference to the name of the daycare where the 49 children were killed. The daycare was owned by the Mexican Social Security Institute (IMSS).[13] Two years later, multiple bronze statues of children's shoes with the names of the victims were placed next to it.[14] | IMSS Headquarters, Paseo de la Reforma Avenue, Colonia Juárez | 5 June 2017 | ||

|

5 June 2019 | |||||

|

49 white crosses with the names of the victims.[15] | Secretariat of the Interior Offices, Abraham González Street, Colonia Juárez | 3 November 2020 | |||

|

David Ramírez and Miguel Ángel Rivera, who were kidnapped on 5 January 2012. Although the ransom payment was made, both were not returned and their whereabouts or conditions are unknown.[13] | The plaque calls for padlocks to be placed as a sign of protest.[16] | In front of the High Court of Justice Building, Paseo de la Reforma Avenue, Colonia Juárez | 5 January 2018 | ||

|

19 February 2018 | The 65 miners that died during the 2006 Pasta de Conchos mine disaster. | The main anti-monument features a 65 number that supports a plus symbol. The symbol has written a legend that says "With one voice, rescue now!", as well as the names of all the victims of the collapse.[11] The following day, across the street a cage with 63 helmets with the names of the victims that were not rescued was placed buried with charcoal lumps.[17] | In front of the Mexican Stock Exchange Building, Paseo de la Reforma Avenue, Colonia Juárez | 18 February 2018 | |

|

The victims of the Tlatelolco massacre | The anti-monument features a white dove and a plaque that blames the Government of Mexico and the Mexican Armed Forces for the massacre.[11] | In the corner of Madero Street and the Zócalo, Colonia Centro | 2 October 2018 | ||

|

Antimonumenta | Victims of femicide | It was placed by mothers and relatives of victims of feminicide, during the march #8M for the International Women's Day.[18] | In front of the Palace of Fine Arts, Juárez Avenue, Colonia Juárez | 8 March 2019 | |

|

It was installed during the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women to memorialize the women murdered in the state of Mexico.[19] | State of Mexico | In front of the municipal palace of Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl | 25 November 2019 | ||

|

Antimonumenta | It was installed during the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women to memorialize the women murdered in the state of Jalisco.[20] | Jalisco | Plaza de Armas, Colonia Centro, Guadalajara | 25 November 2020 | |

|

Antimonumenta (Banca Roja)[21] | It was installed during the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. It has a plaque that reads "In memory of all the women murdered by those who claimed to love them or just because they were women" in Spanish.[22] | In front of the Rotonda de los Jaliscienses Ilustres, Hidalgo Avenue, Colonia Centro, Guadalajara | |||

|

It was installed during the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. It reads "In memory of all the female children, adolescents and women victims of femicide violence. Truth and Justice!" in Spanish.[23] | Hidalgo | Plaza Juárez, Colonia Centro, Pachuca | |||

| It was installed during protests where the feminists took the Chetumal Congress. The anti-monument was later destroyed and a replica was installed.[24] | Quintana Roo | Chetumal Congress, Colonia Barrio Bravo, Chetumal | 30 November 2020 | |||

| It was installed during International Women's Day protests. | Veracruz | Parque Apolinar Castillo, Colonia Centro, Orizaba[25] | 7 March 2021 | |||

| Antimonumenta | Michoacán | Fuente de las Tarascas, Colonia Centro, Morelia[26] | 8 March 2021 | |||

| Veracruz | Port of Veracruz, Colonia Ignacio Zaragoza, Veracruz City[27] | |||||

|

Women Who Fight Roundabout | The sculpture was placed on the empty plinth of the Columbus Roundabout.[28] | Mexico City | Old Columbus Roundabout, Paseo de la Reforma, Colonia Juárez | 25 September 2021 | |

| It was installed during the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women to memorialize the women murdered in the state of Oaxaca.[29] | Oaxaca | Fuente de las 8 Regiones, Colonia Reforma, Oaxaca City | 25 November 2021 | |||

| It was installed during the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women to memorialize the women murdered in the state of Yucatán.[30] | Yucatán | Paseo de Montejo, Mérida | ||||

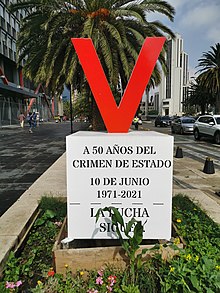

|

The victims of the 1971 Corpus Christi massacre | The monument features a red V and phrases that blame the Government of Mexico for the massacre.[31] | Mexico City | Juárez Avenue and Humboldt Street | 10 June 2021 | |

|

, who opposed the construction of a federal hydroelectric plant in his community. | One year after his assassination, a bust was placed in the school named after him in the community of Amilcingo, Morelos.[32] The next day, after a related march in Mexico City, a replica of the bust (pictured) was placed in the Zócalo square.[33] | Morelos | Amilcingo, Temoac Municipality | 20 February 2020 | |

| Mexico City | Zócalo, Colonia Centro | 21 February 2020 | ||||

|

The 72 migrants murdered during the 2010 San Fernando massacre | It was installed to remember that migration is a human right.[34][35] | In front of the Embassy of the United States Building, Paseo de la Reforma, Colonia Juárez | 22 August 2020 |

Notes[]

- ^ Because most of the anti-monuments are unnamed anonymous works, and the press refers to them simply as "Antimonumentos", some names are unofficial and use recognizable elements to distinguish them from other similar works.

See also[]

- Feminism in Mexico

- Memorial to Victims of Violence in Mexico, a memorial installed by the government in 2013

References[]

- ^ a b c d e f g "Antimonumentos: intervenciones, arte, memoria – InfoActivismo.org" (in Spanish). Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ Seligmann-Silva, Márcio (April 2016). "Antimonumentos: trabalho de memória e de resistência". Psicologia USP (in Portuguese). 27 (1): 49–60. doi:10.1590/0103-6564d20150011.

- ^ Lacruz, M. Elena; Ramírez, Juan (2017). "Anti-monumentos. Recordando el futuro a través de los lugares abandonados". Revista Rita. No. 7. pp. 86–91.

- ^ a b c d González Díaz, Marcos (8 December 2020). "Why are 'anti-monuments' appearing in Mexico (and how they reflect the darkest episodes in its recent history)". Digismak. BBC News. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ a b Galván, Melissa (13 March 2021). "México, el país de los antimonumentos que exigen acabar con la impunidad" [Mexico, the country of anti-monuments demanding an end to impunity]. Expansión. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Hernández, Eunice (2 October 2020). "Dimensiones y paradojas de los antimonumentos en la Ciudad de México" [Dimensions and paradoxes of the anti-monuments in Mexico City]. Este País (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Muñoz Ramírez, Gloria (3 June 2019). "Antimonumentos, la ruta por la memoria amenazada" [Anti-monuments, the route for threatened memory]. Desinformémonos.org (in Spanish). Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ a b Tello Arista, Irene (May 2021). "Arrebatar las narrativas" [To snatch the narratives]. Revista de la Universidad de México (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ "Cinco Estados de México colocan antimonumenta por los feminicidios" [Five states of Mexico place the Animonumenta due to femicies]. Voces Feministas (in Spanish). Tuxtla Gutiérrez. 2 December 2020. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ García, Paula (6 March 2019). "Este es el origen de los símbolos feministas". Hipertextual. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 20 November 2021.

- ^ a b c ""Anti-monuments" commemorating tragedies flourish in Mexico City". EFE. Mexico City. 18 November 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Colocan caparazón de 43 tortugas en el antimonumento de Ayotzinapa (Video)". Aristegui Noticias (in Spanish). 25 September 2018.

- ^ a b Guthrie, Amy (30 June 2019). "Mexico 'anti-monuments' recall dark moments, demand justice". ABC News. Associated Press. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Ortiz, Alexis; Miranda, Perla (5 June 2019). "Instalan zapatitos de bronce en antimonumento de la Guardería ABC". El Universal (in Spanish).

- ^ "Rechazan padres de víctimas de Guardería ABC reunirse con Encinas". MVS Noticias (in Spanish). 3 November 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ Rodríguez, Marco (9 March 2018). "El Memorial de David y Miguel". Grupo Radiofónico y Medios. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Gómez, Nancy (19 February 2019). "Instalan nuevo antimonumento por mineros de Pasta de Conchos". SDPNoticias (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Gómez, Nancy (8 March 2019). "Marcha #8M2019; instalan antimonumenta por feminicidios". SDPNoticias (in Spanish). Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ "Edomex, epicentrode feminicidios, olvidado en marcha feminista". La Silla Rota (in Spanish). 26 November 2019. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Instalan la Antimonumenta, parte de la lucha feminista, en Plaza de Armas" [Antimonumenta, part of the feminist struggle, installed at Plaza de Armas]. Notisistema (in Spanish). 25 November 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- ^ "Feminicidios. Mujeres de Jalisco colocan antimonumenta vs violencia". www.milenio.com (in Mexican Spanish). Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ Ruiz, Josefina (25 November 2020). "Colocan antimonumenta en memoria de mujeres asesinadas en la Rotonda". Milenio. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ Rosas, Lorena (25 November 2020). "#25N: Colocan memorial por víctimas de feminicidio en Plaza Juárez". La Silla rota (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Maldonado, Joana (25 June 2021). "Reinstalarán la antimonumenta este sábado en Chetumal". La Jornada (in Spanish). Cancun. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Renaud, Jhennifer (7 March 2021). "[Video] Instalan antimonumenta; Colectivos exigen justicia". El Sol de Orizaba (in Spanish). Orizaba. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Padilla, Blanca (25 April 2021). "Colectivos reinstalan antimonumenta en las Tarascas" [Colevtives reinstall Antimonumenta at Las Tarascas]. Meganoticias (in Spanish). Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- ^ "Mujeres feministas buscan dialogo para reubicar la 'Antimonumenta'". El Dictamen (in Spanish). 10 March 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Mexican feminists install a statue of a woman to replace one where Columbus stood". The Fresno Bee. Mexico City. EFE. 25 September 2021. Retrieved 9 October 2021.

- ^ Jiménez, Christian (25 November 2021). "Con indignación y Antimonumenta contra feminicidios, mujeres de Oaxaca exigen freno a la violencia" (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "After demonstrating Feminist Anti-monument is unveiled in Paseo de Montejo". The Yucatan Times. Mérida, Yucatán. 26 November 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Colocan antimonumento por víctimas del "Halconazo" en Avenida Juárez". El Universal (in Spanish). 10 June 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Ríos, Emmanuel (12 February 2020). "Develarán monumento a Samir Flores en Amilcingo". El Sol de Cuautla (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ Pillardo, Ángeles (21 February 2020). "Instalan busto de Samir Flores en el Zócalo de la CDMX". SDPNoticias (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Colocan antimonumento por los 72 migrantes masacrados en San Fernando". Desinformémonos (in Spanish). 22 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ "Colocan antimonumento frente a embajada de EU". Excélsior (in Spanish). 22 August 2020. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

Further reading[]

- Díaz Tovar, Alfonso; Ovalle, Lilian Paola (2018). "Antimonumentos. Espacio público, memoria y duelo social en México". Aletheia (in Spanish). 8 (16): 86–91. ISSN 1853-3701.

External links[]

Media related to Antimonumento at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Antimonumento at Wikimedia Commons

- Anti-monuments in Mexico

- Feminism in Mexico

- Monuments and memorials in Mexico