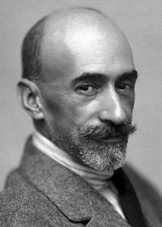

Antonio Pérez de Olaguer

Antonio Pérez de Olaguer Feliu | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Antonio Pérez de Olaguer Feliu 1907 Barcelona, Spain |

| Died | 1968 Barcelona, Spain |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | entrepreneur |

| Known for | writer, editor, publisher |

| Political party | Carlism |

Antonio María Pérez de Olaguer Feliu (1907–1968) was a Spanish writer and a Carlist militant. As a man of letters he was recognized by his contemporaries for travel literature, novel and drama, gaining much popularity in the 1940s and 1950s. Today he is considered mostly a typical representative of early Francoist culture and his works are denied major value. As a Carlist he remained in the back row, though enjoyed enormous prestige among the Catalan rank and file. For decades he worked to bridge the gap between two groups of Catalan Carlists, the Javieristas and the Sivattistas.

Family and youth[]

Antonio Pérez de Olaguer descended from distinguished families both along the paternal and the maternal line. The ancestors of his father originated from Andalusia; his grandfather, (1829-1889),[1] came from Cádiz.[2] A physician serving in the navy, in the mid-19th century he engaged in trade with the Philippines, then managed state contracts in the islands, and eventually developed own retail and real estate business in Manila. He became one of the Philippine tycoons and left a fortune.[3] The business was inherited by his sons: Antonio's father Luis Pérez Samanillo (1868–1936) and Rafael, who enlarged it further on managing two family-owned companies, R. Pérez Samanillo y Cía and Pérez Samanillo Hermanos.[4] They contributed to urbanization of Manila; the brothers owned much of the Paco district, dried the area and commenced residential development; a street in the city still bears their name.[5] One of few art-decó buildings in Manila used to be their department store.[6]

Antonio's maternal ascendants were related to overseas; his great-great-grandfather Antonio Olaguer Feliu Heredia served as virrey del Rio de la Plata, his son and Antonio's great-grandfather José Olaguer Feliu Azcuenaga opted for Argentine nationality;[7] his son and Antonio's grandfather José María Olaguer Feliu Dubonet (1827-1881) was born and lived in the Philippines.[8] His son and Antonio's maternal uncle general José Olaguer Feliú Ramirez became the minister of war in 1922 and later remained active as a primoderiverista politician. His daughter and Antonio's mother, Francisca de Olaguer Feliú Ramirez (1865–1908),[9] also born and raised in the Philippines,[10] married Luis Pérez; the couple settled in Manila.

The collapse of Spanish rule in 1898 did not affect the Pérez business much. However, Luis started to invest in Spain, mostly in Catalonia. In the early 20th century the family permanently settled in a luxury Barcelona residence,[11] managing their overseas economy remotely.[12] They had 9 children, some of them born in the Philippines; Antonio was the youngest one.[13] There is almost no information on his childhood and early teenage years, except that he was raised in Barcelona and very early orphaned by his mother. As in 1911 his father remarried with Asunción Lladó (1884-1963),[14] Antonio was brought up by his step-mother. He studied commerce in an unidentified Jesuit institution;[15] and travelled heavily, accompanying his father during voyages to the Philippines. Later he inherited at least part of the overseas business.[16]

In the late 1920s or very early 1930s[17] Antonio married Sara Moreno Calvo y Ortega (1905-1968).[18] She was the daughter of an Andalusian winegrower[19] and Liberal cacique Guillermo Moreno Calvo;[20] he passed into history when later sub-secretary of the Lerroux cabinet,[21] becoming the key protagonist of the 1935 Nombela affair.[22] The couple settled at calle Muntaner in Barcelona;[23] they had 5 children, all of them sons[24] and all cultivating literary interest of their father in editorial, publishing, theatrical and librarian fields.[25] The best-known of them, Gonzalo Pérez de Olaguer Moreno, became an iconic personality of the Catalan theatre and drama. Antonio lived[26] to see 17 grandchildren.[27]

Writer[]

Pérez de Olaguer was a prolific writer and claimed fathering some 50 books.[28] The genre which prevails is non-fiction; it may be subdivided into 4 sub-genres. Pérez de Olaguer commenced literary career in 1926 with travel literature,[29] followed – as he travelled around the world 6 times[30] – with subsequent volumes in 1929,[31] 1934,[32] 1941[33] and 1944;[34] the last one is an account of truly amazing tour around the world in the midst of the Second World War.[35] Historiography is about three volumes featuring Catholic personalities from the recent past (1933-1940)[36] and a book on his own father (1967).[37] Four volumes of essays anchored in daily life (1950-1953)[38] were written "to cheer up in the dark times". However, Pérez de Olaguer became best known for his works intended to document Republican horror and Nationalist heroism during the Spanish Civil War. He issued 3 volumes discussing Republican atrocities[39] and 2 volumes honoring the Carlist volunteers (1937-1939).[40] The work falling into the same testimonial literature which gained him international recognition was a 1947 work documenting the Japanese barbarity in the Philippines.[41]

Another genre favored by Pérez de Olaguer was novels. They form two distinctly different groups. Four works are marked by grotesque style; except one case[42] the plot is set in contemporary times and the protagonists are involved in twisted intrigues which seem to underline absurdities of daily life, all told in a farcical, optimistic, amusing manner.[43] In terms of content they are benevolent reflections on human confused nature.[44] Entirely different are three novels written during the Civil War.[45] Light message gave way to moralizing objectives related to promotion of the Nationalist cause and grotesque gave way to the horror of wartime setting; what remained was author's optimism and a penchant for a plot anchored in relations between males and females.

In terms of drama Pérez de Olaguer underwent internship period in the early 1930s; working for Enrique Rambal he co-adapted novels for stage performance, tasked with providing intriguing episodic dramas which merged high action with musical interludes.[46] Likewise he adapted his own novel into a 3-act play (1933),[47] which was actually staged.[48] His greatest success as a playwright came with Más leal que galante (1935), written together with Benedicto Torralba de Damas. Set in the Third Carlist War and written in a light verse, the comedy featured a complex romance intrigue with clear Carlist message in the background;[49] its popularity stemmed from smart and pacy intrigue, well-written rhymed dialogues and a blend of romantic and patriotic features. The play was performed countlessly especially in the Nationalist zone[50] and later in the Francoist Spain;[51] there were great Spanish actors like Carmen Díaz starring[52] and great political personalities like Queipo de Llano attending.[53] Another comedy followed in 1935;[54] it failed to repeat the success, though it was later performed in the Philippines and attended by president Quirino.[55] In the 1950s Pérez de Olaguer kept adapting novels for Rambal[56] and wrote libretto for a zarzuela.[57] Only one of his own late plays was performed commercially;[58] others were one-act dramas performed at amateur or religious stages.[59]

Publisher, manager, periodista[]

For some 35 years Pérez de Olaguer remained active in a broadly defined culture; perhaps his most important role was this of a publisher, who animated a number of Catholic cultural initiatives. The key one was , a Barcelona-based review set up by his father in 1908[60] and following some periods of lesser activity still issued in the early 1930s. It was at this time that the young Antonio assumed management of the weekly;[61] following the Civil War La Familia, already as his own property,[62] was re-launched and enjoyed its heyday in the 1950s.[63] Pérez de Olaguer kept running the review as its director[64] until the late 1960s;[65] at some stage he tried to build a satellite infrastructure, launching periodical veladas literarias.[66] Until his death La Familia was one of key platforms of popular Catholic culture in Catalonia, though its importance declined as secularization and consumer lifestyles advanced. Other of Pérez de Olaguer's editorial activities were less successful: Traditionalist weekly Alta Veu[67] and humorous reviews Don Fantasma[68] and Guirigay,[69] launched in the mid-1930s, proved short-lived, though Momento[70] kept appearing in 1951-1954.[71]

Pérez de Olaguer himself started contributing to press titles in 1930.[72] He soon commenced co-operation with La Vanguardia[73] and by the board was dubbed "nuestro collaborador".[74] Starting 1933 he kept supplying pieces to established Barcelona reviews La Cruz[75] and especially to Hormiga de Oro[76] though also to minor titles.[77] Initially his contributions were related to his experience as a traveler and later focused also on theatre;[78] starting 1933 they were increasingly flavored with Catholic and Traditionalist outlook.[79] This thread climaxed during the Civil War; once Pérez de Olaguer resumed writing in October 1936[80] his light and humorous style gave way to serious if not pathetic tone.[81] He kept publishing especially in El Pensamiento Alavés and a Carlist infantile weekly Pelayos; after 1937 his activity decreased. Following the war Pérez de Olaguer contributed to Enciclopedia universal ilustrada europeo-americana,[82] and to Catholic reviews; the popular ones were intended for La Familia, more sophisticated ones were published in Cristiandad; his credo was laid out in a 1957 essay Ante la supuesta inexistencia del escritor católico.[83]

In the Francoist era Pérez de Olaguer remained engaged in numerous Catalan Catholic cultural initiatives, those flavored by Traditionalism rather than those advancing a Christian-Democratic outlook. He was the moving spirit behind 1954-co-founded Asociación de San Francisco de Sales,[84] acted in Amigos de Sagrada Familia[85] and Congregaciones Marianas,[86] lectured at Schola Cordis Iesu[87] and galvanized Patronato O.F.O.R.S.[88] In terms of literature he presided over Agrupación Literaria Ibero-Americana;[89] in terms of theatre headed Fomento del Espectáculo Selecto y del Teatro Asociación,[90] contributed to Congreso Regional de Teatro de Aficionados[91] and the CAPSA amateur theatre.[92] In terms of charity he animated Asociación de Amigos de San Lázaro[93] and especially supported Leprocomio de Fontillas,[94] apart from countless other involvements in educational[95] or religious events.[96]

Carlist: early decades[]

Pérez de Olaguer's ancestors lived mostly overseas and seemed detached from daily Spanish politics; the only information on their preferences available[97] is that his father was a fervent Catholic.[98] The young Antonio initially did not reveal any penchant; it is only in the early 1930s that his writings got saturated with Traditionalism. Exact mechanism of his access to Carlism is not known,[99] yet in 1933 it seemed apparent,[100] perhaps confirmed in 1934.[101] His writings and publications aside[102] there is no confirmation of his engagement in Carlist structures. It is not clear whether Antonio joined requeté military gear-up and whether on July 19 he engaged in the coup.[103] In the mayhem that followed he left Barcelona for Genoa.[104] He entered the Nationalist zone some time before November 1936 and offered his services to Junta Nacional Carlista de Guerra; Pérez de Olaguer was seconded to its Prensa y Propaganda section, touring the area controlled and gathering information on the fallen requetés.[105] He also kept advancing the Carlist cause in numerous books and press publications. His position versus the Unification Decree and buildup of the Francoist regime is not clear; after 1937 his activity as author declined sharply, yet in 1939 Franco watched the victory parade in Barcelona from the balcony of Casa Pérez Samanillo.[106]

Pérez de Olaguer spent part of the early 1940s overseas and there is no information on his Carlist activities, except hosting Fal Conde during the 1942 Montserrat festivities.[107] During growing bewilderment of Carlism Pérez de Olaguer did not engage in the daily party business[108] yet due to his standing as a writer, though also thanks to his easy-going, serene,[109] and modest conduct he enjoyed great prestige among the Catalan party rank and file.[110] He remained loyal to leadership of Fal and to sovereignty of Don Javier; the regent appreciated him personally. Taking advantage of his position in the mid-1940s Pérez de Olaguer tried to mediate between two increasingly hostile fractions of Catalan Carlists: cautious supporters of Fal Conde, who stuck to the regentialist solution, and activist supporters of regional leader Maurici de Sivatte, who demanded that Don Javier openly challenges Franco and declares his own reign. In 1947 he addressed the claimant with a letter, asking to take action and prevent forthcoming breakup.[111] Himself he tended to side with the Sivattistas,[112] noting that Spain needed "legitimate chief of state".[113] Don Javier took notice but did not take action and the conflict escalated. In early 1949 Fal travelled to Barcelona seeking last-minute reconciliation, but Pérez de Olaguer informed him that "por aquel camino el carlismo no podía continuar".[114] Few months later in another letter he advocated more open anti-Francoist stand and noted that caudillo's fate might be this of Hitler and Mussolini.[115] However, Fal's strategy prevailed and Sivatte was dismissed from the Catalan jefatura.

Carlist: late decades[]

Pérez de Olaguer remained embittered about Sivatte's dismissal and protested to Fal;[116] however, while Sivatte soon distanced himself from the party, for Pérez de Olaguer obedience towards Don Javier remained an untouchable principle.[117] The Catalan Carlists held him in high esteem and suggested that it is Pérez de Olaguer who becomes the regional jefe;[118] however, despite insistence on part of the regent Pérez declined the offer, pledging instead that he would work to unite all Catalan Carlists.[119] Indeed, he did, and the early 1950s are marked by his efforts to this end. Unwavering in his loyalty to Don Javier he kept challenging the regency formula. The campaign produced success in 1953; Don Javier issued a vague document, hailed by Consejo de Comunión Tradicionalista as claim of monarchic rights; their communiqué was co-signed by Pérez de Olaguer.[120] The move triggered what looked like rapprochement between Javieristas and Sivattistas; it climaxed when two groups, since 1949 staging 2 separate Montserrat feasts, agreed to have one, very much the result of Pérez de Olaguer's conciliatory work.[121]

In 1956 Pérez de Olaguer together with Sivatte[122] met Don Javier in Perpignan to discuss further alignment and prevent would-be dynastic accord with Don Juan; the Carlist king signed appropriate statement but insisted it is kept private. The document was to be stored by Sivatte but Don Javier soon developed second thoughts and demanded it is to be in custody of Pérez de Olaguer, the king's trusted man in Catalonia.[123] To his great surprise, Sivatte made the Perpignan pledge public during the meeting of Carlist executive in Estella,[124] which heavily damaged Don Javier's relations with Pérez de Olaguer.[125] However, when in 1957 Sivatte launched an openly rebellious Carlist grouping known as RENACE Pérez de Olaguer did not join, in the late 1950s limiting himself to maintaining friendly relations with Sivatte and his collaborators, like Carles Feliu de Travy.[126] His general stand seemed constant; basking in prestige among Catalan Carlists he did not engage in any party activity yet did engage in common, mostly religion-flavored initiatives.[127]

Pérez de Olaguer avoided entanglements in Francoist structures though he used to meet high regional officials of the regime, be it provincial civil governor,[128] capitán general[129] or alcalde.[130] The purpose of these meetings is not clear; it seems he represented various non-political institutions seeking assistance.[131] However, in the early 1960s Pérez de Olaguer started to demonstrate that also politically he sort of acknowledged the stability of Francoist setting. During local elections of 1963 he lent his support to one Carlist candidate[132] and in the Cortes elections of 1967 to another.[133] Following 30 years of the regime his trust in instauration of the Traditionalist monarchy decayed; in a 1966 letter to Don Javier he diagnosed that "el Carlismo, más dividido que nunca, más lleno de rencor que en otras ocasiones, languidece, y por paradoja sólo diríase alimentado, vivificado, por los antiguos partidarios de Sivatte".[134] He repaired relations with the house of Borbón-Parma and hosted Don Carlos Hugo and his wife Irene in his house during their mid-1960s interview with Sivatte; it is not clear whether he shared Sivatte's damning opinion about the prince.[135]

Reception and legacy[]

Pérez de Olaguer's early attempts were acknowledged with patronizing tone; critics admitted potential, unbiased fresh look and writing ease yet stayed cautious and some alluded to a premature debut,[136] though Jacinto Benavente approvingly prologued his 1934 volume.[137] Pérez de Olaguer gained some attention due to his grotesque novels and plays; commended for gracious style,[138] original humor[139] and optimistic humanism[140] they were placed in the farcical tradition of Rabelais[141] or Molière.[142] In the mid-1930s his works started to collect praise in conservative realm, which noted Christian spirit[143] and Traditionalist vision.[144] Más leal que galante earned Pérez de Olaguer great popularity among the Carlists;[145] in 1935 he was already invited as a literary arbiter[146] and received homages.[147] During the Civil War and early Francoism Pérez de Olaguer emerged among more popular writers; some of his works were re-printed 4 times,[148] Más leal was continuously staged commercially and occasionally he kept attending literary juries.[149] He remained an author catering to popular taste and was rewarded by the public rather than by critics and awards.[150] Starting mid-1950s his literary production declined as he focused on Catholic Barcelona reviews instead. Since their circulation remains unknown also their impact remains to be gauged, yet it seems that La Familia counted among key platforms of popular Catalan Catholicism.

After his death Pérez de Olaguer went into oblivion; none of his works has been re-published. In the post-Francoist era the skyrocketing popularity of Gonzalo Pérez de Olaguer – never referred to as the son of Antonio[151] – has entirely eclipsed the memory of his father. Pérez de Olaguer has not made it to history of the Spanish literature and is disregarded not only in synthetic accounts[152] but also ignored[153] or barely mentioned[154] in detailed studies. If referred, he merits scholarly attention as a representative of cultural outlook of early Francoism rather than as an individual. Scholars quote his name when presenting typical features, clichés and traits of Francoist culture, and if admitted importance it is only because some counted him among key contributors[155] to or "más destacados cultivadores"[156] of most characteristic cultural features in the nationalist zone. The ones listed are: lambasting the Republicans as foreign-inspired anti-Spain,[157] depicting them as bestial brutes,[158] disseminating the vision of judeo-masonic plot,[159] idealizing own heroic men,[160] constructing the Cruzada logic,[161] building a myth of Traditionalist Navarre,[162] bending historical truth to serve own political preferences[163] and cultivating sex stereotypes.[164] His individual literary contribution is dismissed as "cuentos escritos en un tono didáctico-moralizante".[165]

In the Carlist realm Pérez de Olaguer is occasionally recorded on private blogs[166] and official Comunión Tradicionalista sites.[167] His testimonial literature on Republican terror was widely quoted during the Francoist era. As a documentary it has not been proven incorrect until today; at times it remains quoted by scholars though they usually[168] stigmatize Pérez de Olaguer as a Nationalist partisan,[169] a source which "does not inspire confidence"[170] or "ideologically committed lay Catholic".[171] Internationally he was acknowledged mostly thanks to work on Japanese atrocities in the Philippines and until today the volume is considered "deeply and broadly researched platform" that every scholarly investigation of the issue must commence with.[172]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ Manuel Joseph Valerio María de los Dolores Marcos Pérez Maqueti entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ and married Augustina Samanillo Fragoso, also from Cádiz, Antonio Pérez de Olaguer, Mi padre, un hombre de bien, Sevilla 1967, p. 41.

- ^ his wealth was estimated at 2m pesos, El Día 02.08.89, available here

- ^ see Filipinas Photo Collection, [in:] Skyscrapercity forum (link unavailable as blacklisted by Wikipedia)

- ^ Hotel de Oriente: the hotel that became a library, [in:] The Crafty Historian blog 01.09.14, available here

- ^ designed by Andres Luna de San Pedro and built in 1928, it was known as Edificio Perez-Samanillo. Now it is known as First United Building, see wikimapia service, available here

- ^ Francisca de Olaguer-Feliu Ramirez entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here. Some other online services provide wrong data, see e.g. NN de Olaguer Feliú y Ramirez entry, [in:] Geni genealogical service, available here

- ^ birth and death dates are quoted after José María de Olaguer-Feliu y Dubonet entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here, which seemes to be a well-informed source. Information about his birth place – somewhat odd compared to itinerary of his father, related to Spain and Argentina, though still possible – is repeated after Tomás Makintach Calaza, Memorial genealogico, histórico, y heraldico de la casa de Azcuenaga, [in:] Genealogia. Revista del Instituto Argentino de Ciencias Genealogicas 17 (1977), p. 157, the source which wrongly quotes his death date as 1857

- ^ Francisca de Olaguer-Feliu Ramirez entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here, Perez de Olaguer 1967, p. 120

- ^ Antonio Pérez de Olaguer Feliu himself provides a different maternal ancestry line. According to his own account, the virrey Antonio Olaguer Feliu Heredia was his great-grandfather (not great-great-grandfather); his son was a „José Olaguer Feliu” (grandfather, no closer information provided) who married Ladislaa Ramirez; their daughter was Francisca Olaguer Feliu Ramirez (mother), see Pérez de Olaguer 1967, p. 88. It would be odd not to trust a first-hand account, yet the dates seem incompatible. The birth date of Antonio Olaguer Feliu Heredia (1742) and this of his alleged granddaughter Francisca (1865) would have been separated by some 120 years

- ^ Caras y Caretas 20.01.12, available here

- ^ he was animating Cámara de Comercio Española de Filipinas, Vida Marítima 30.01.21, available here

- ^ Luis Pérez Samanillo entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ Asunción Lladó Rarmírez entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here. Asuncion was a step-sister of his late wife Francisca. Francisca's father died early and the widowed Francisca's mother re-married with Isidro Lado. Their daughter was Asuncion, Perez de Olaguer 1967, pp. 88-89

- ^ Enciclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europeo-Americana, Suplemento Annual 1967-1968, Madrid 1968, p. 392, referred after Antonio Pérez de Olaguer y Feliu, [in:] La Tradicio de Catalunya service, available here

- ^ with income from the Philippine business Perez did not depend on his literary production. It is not clear when the family shut down the overseas engagements; the iconic Manila building, Edificio Perez-Samanillo, was sold to the Americans in the early 1960s

- ^ in 1928 the future wife was already very close with the Perez family, La Vanguardia 04.11.28, available here; their 3rd child was baptised in December 1934, ABC 11.12.34, available here

- ^ she passed away 2 months after her husband, La Vanguardia 25.04.68, available here

- ^ Josep Armengol i Segú, El poder de la influencia: geografía del caciquismo en España (1875-1923), Madrid 2001, ISBN 9788425911521, p. 35

- ^ he was the civil governor of the Huelva province in 1911 and later joined the Canalejista faction, María Antonia Peña Guerrero, Clientelismo Político y Poderes Periféricos Durante la Restauración: Huelva, 1974-1923, Huelva 1998, ISBN 9788495089175, pp. 94, 314, 423. In 1910-1923 he served in the Cortes, see his entry on the official Cortes site, available here

- ^ ABC 11.12.34, available here

- ^ for details see Donato Ndongo-Bidyogo, Guinea durante la II República. El „escandalo Nombela”, [in:] Endoxa 37 (2016), pp. 101-119

- ^ César Alcalá, D. Mauricio de Sivatte. Una biografía política (1901-1980), Barcelona 2001, ISBN 8493109797, p. 52

- ^ in an interview shortly before death Pérez de Olaguer admitted "cinco hijos", see La Vanguardia 14.06.67, available here. However, a well-informed genealogical service claims he had also one daughter, see Antonio Maria Pérez de Olaguer Feliu entry, [in:] Geneanet service, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 14.06.67, available here

- ^ Pérez de Olaguer was of rather good health, as certified by his constant travelling. His death came entirely unexpected and is attributed to a sudden heart attack, La Vanguardia 30.03.68, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 14.06.67, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 14.06.67, available here. Only some 30 books have been identified here; perhaps he meant also re-editions

- ^ Ensayos literarios, a set of juvenile reflections on his global journeys, La Vanguardia 15.01.26, available here

- ^ the last time in the early 1960s; La Vanguardia 12.05.60, available here; needless to say he had many adventures, including sinking of a ship he travelled on, La Vanguardia 16.12.60, available here. Perhaps the most dramatic story occurred in relation to a domestic flight from Madrid to Barcelona; the flight was fully booked and at the airport Pérez de Olaguer ceded his place to someone who urgently wanted to fly but had not ticket. The plane crashed, killing all those on board. An unsourced story referred after Alcalá 2001, p. 79

- ^ De Occidente á Oriente por Suez

- ^ Mi vuelta al mundo

- ^ Novelista que vio las estrellas, an account of Pérez de Olaguer meeting the Hollywood stars in the US

- ^ Mi segunda vuelta al mundo

- ^ his voyage, apparently undertook between 1942 and 1944, took him across many frontlines. First from neutral Spain Pérez de Olaguer travelled to Fascist Italy, where he visited the Carlist sanctuary in Trieste. Then he crossed to the British-held Egypt, along the Asian coast made it to India and then, also by sea, to the Japanese-held Philippines. Next he crossed the Pacific and the United States (already in war), and in the midst of U-boot warfare crossed the Atlantic to return to Spain. This incredible voyage climaxed during his stay in the Philippines. The Japanese were initially very corteous towards the Spanish colony on the islands and the rupture occurred in wake of the Laurel affair, details of Spanish-Japanese relations in the occupied Philippines in Florentino Rodao, La ocupación japonesa en Filipinas y etnicidad hispana (1941-1945), [in:] Gerónimo de Uztariz 25 (2009), pp. 12-18

- ^ El canonigo Collell (1933), Piedras vivas (1939) and El padre Pro precursor (1940)

- ^ Mi padre, un hombre de bien (1967)

- ^ Son mis humores reales (1950), El mundo por montera (1950), Al leer será el reír Aventura de amor y de viaje (1950), Hospital de San Lazaro (1953). The last one, sub-titled "Autobiografía novelesca", was a set of stories integrated by the personality of their protagonist, the author

- ^ El terror rojo en Cataluña (1937), El terror rojo en Andalucía (1938), El terror rojo en la Montaña (1939). Later he also used to write biographies of some of the executed – e.g .Melquiades Alvarez - for Enciclopedia Espasa, Josefina Cuesta Bustillo, Tiempo y recuerdo: dimensiones temporales de la memorisa política (España 1936-2000), [in:] Carlos Navajas Zubeldía (ed.), Actas del III Simposio de Historia Actual, vol. 2, Logroño 2002, ISBN 8495747227, p. 28

- ^ Los de siempre (1937) and Lágrimas y sonrisas (1938). Later he added also Estampas carlistas (1950)

- ^ El terror amarillo en Filipinas (1947); its abridged English translation, titled Terror in Manila, was published in Manila in 1945. The oldest brother of Antonio, Luis, was killed "a manos de la soldatesca nipona", Perez de Olaguer 1967, p. 99

- ^ ¡Paso al rey! (1931) shares the same style yet is set in a fantastic background; it features a story of two cities/peoples in Africa, Alfenia and Tosaca

- ^ Españolas de Londres (1928), La ciudad que no tenia mujeres (1932) and Memorias de un recién casado (1939). The last one was reportedly written in the early 1930s and based on personal experiences of the author, Hoja Oficial de la Provincia de Barcelona 21.08.39, available. here. It was perhaps Pérez de Olaguer's most successful novel, re-published 4 times, La Vanguardia 14.06. 67, available here

- ^ though ¡Paso al rey! seems to advance a veiled Traditionalist message. Of two fantastic cities/peoples depicted one was tranquil and ordered, while another criminal and violent. The latter invaded the former and apparently succeeded in overcoming resistance, but there was hope that fortune might change, La Hormiga de Oro 24.12.31, available here

- ^ El romance de Ana María (1937), Amor y sangre (1938) and Elvira, Tomás Rúfalo y yo (1939), all partially set in Barcelona after the failed 1936 coup. The last one features the most complex plot; Tomás is an emotionally unstable marxist, half-good (hides the protagonist in red Barcelona) and half-bad (murders a priest). The two meet later on the battleground and Tomás is mortally wounded. He confesses, though only to comfort his mother, and suddenly finds peace of mind before passing away, referred after Piotr Sawicki, La narrativa española de la Guerra Civil (1936-1975). Propaganda, testimonio y memoria creativa, Alicante 2010, pp. 138-139

- ^ Edward Malcolm Batley, David Bradby, Morality and Justice: The Challenge of European Theatre, Amsterdam 2001, ISBN 9789042013988, p. 195

- ^ La ciudad que no tenía mujeres, La Libertad 12.07.33, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 09.07.33, available here

- ^ a Carlist officer falls in love with a mysterious beauty who in fact is a Liberal spy, which leads to military disaster. He is to be executed but another female Marta begs for his life. The king allows Andrés to redeem his guilt on the battlefield, which he does by capturing the enemy standard

- ^ e.g. in Palencia, see El Día de Palencia 07.01.37, available here, or in Valladolid, see El Día de Palencia 20.01.37, available here

- ^ the last identified year the play was staged was 1965, La Vanguardia 28.03.65, available here

- ^ El Pensamiento Alaves 05.07.39, available here

- ^ ABC 21.04.37, available here

- ^ En los mares de Oriente, also co-authored with Torralba de Damas. It was set in the Philippines, Ilustración Católica 02.04.36, available here. It was a played in amateur theatres, La Vanguardia 29.02.36, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 28.02.36, available here

- ^ e.g. he co-scripted Otra vez Pimpinella, adaptation of Adventures of Scarlet Pimpernel, Maria M. Delgado, "Other" Spanish Theatres: Erasure and Inscription on the Twentieth Century Spanish Stage, Madrid 2003, ISBN 9780719059766, p. 83

- ^ Entre viñedos (1955), La Vanguardia 01.02.55, available here

- ^ Eva accepta la manzana (1953), played in Teatro Barcelona, La Vanguardia 22.04.53, available here

- ^ in 1961 Pérez de Olaguer penned Occurió en Fátima, one-act play, performed at amateur and religious stages like teatro CAPSA, later managed by his son, La Vanguardia 18.05.61, available here

- ^ Juan María Roma (ed.), Album historico del Carlismo, Barcelona 1933, p. 97

- ^ in 1933 he was already listed as its director, Roma 1933, p. 97

- ^ La Vanguardia 30.03.68, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 27.10.55, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 28.02.57, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 12.06.66, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 08.03.59, available here

- ^ together with Juan Soler Janer, Melchor Ferrer, Historia del tradicionalismo español vol. XXX/2, Seville 1979, p. 136

- ^ Don Fantasma, sub-titled "Afirmación-Humorismo-Lucha", was managed jointly with Torralba de Damas, El Siglo Futuro 19.02.34, available here

- ^ Ferrer 1979, p. 137

- ^ La Vanguardia 22.04.53, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 30.03.68, available here

- ^ compare his 1930 piece on Japan, La Esfera 15.02.30, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 19.01.30, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 07.12.34, available here

- ^ La Cruz 17.08.33, available here

- ^ in 1934-36 he published 22 articles, Raquel Arias Durá, La revista "La Hormiga de Oro". Análisis de contenido y estudio documental del fondo fotográfico [PhD thesis Universidad Complutense], Madrid 2013, p. 194

- ^ like a Barcelona satiric journal Gutiérrez

- ^ see his piece in La Ilustración Católica 16.07.36, the last one identified before outbreak of the civil war, available here

- ^ his first identified piece published after outbreak of the war appeared in La Unión of 28.10.36, available here

- ^ La Unión 31.10.36, available here

- ^ La Unión 05.11.36, available here

- ^ where he wrote the biographies of several prominent figures, among them Carlists like José María de Alvear, Joaquín Beunza, Prince Xavier of Bourbon-Parma, Alfonso María de Borbón y Pintó, Luis Carpio Moraga, Tomás Caylá, Jesús Comín, Servando Conejero Sotos, José Díez de la Cortina y Olaeta, Ángel Elizalde Sainz de Robles, Manuel Fal Conde, Aurelio José González de Gregorio, Manuel González-Quevedo, Miguel Junyent, Francisco Javier Larrú y Sierra, Antonio Molle Lazo, Mario Muslera, Juan Pérez Nájera, Juan de Olazábal Ramery, Ángel Prados Parejo, Juan Carlos de la Quadra Salcedo, Abelardo da Riva y de Angulo, Estanislao Rico Ariza, José Roca y Ponsa, Emilio Ruiz Muñoz, Manuel Sánchez Cuesta, Casimiro de Sangenís, Antonio Sanz Cerrada, Domingo Tejera de Quesada, Benedicto Torralba de Damas and Luis Carlos Viada y Lluch, as well as other right wing politicians like José Calvo Sotelo (8 pages) or Corneliu Codreanu, and writers like Ramiro de Maeztu or Pedro Muñoz Seca, most of whom were killed during the war, Enciclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europeo-Americana (Espasa), 1936-1939 supplement, vol. 1, 1944

- ^ Ante la supuesta inexistencia del escritor católico, [in:] Cristiandad 315 (1957), pp. 141-142. It was sort of a follow up to his much earlier La tragedia de escritor (1934), an 8 page leaflet in defense of Catholic writing

- ^ its declared objective was promotion, edition and dissemination of Catholic press

- ^ La Vanguardia 28.02.57, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 25.06.58, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 26.04.59, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 11.12.63, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 06.11.59, available here

- ^ in 1961 he was vice-president and member of junta directiva of FESTA, La Vanguardia 18.07.61, available here, in the mid-1960s growing to its president, La Vanguardia 19.04.66, available here, but stepping down to honorary membership in 1967, La Vanguardia 24.01.67, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 30.06.59, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 18.01.61, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 28.02.57, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 30.03.68, available here

- ^ for his 1953 lecture on educational topics see La Vanguardia 19.02.53, available here, for a 1964 lecture on theatre and morality see La Vanguardia 28.01.64, available here

- ^ compare La Vanguardia 31.01.63, available here

- ^ apart that his family was not Carlist, Alcalá 2001, p. 79

- ^ which cost him life; having seen the Republican crowd vandalising a Barcelona church Luis Pérez jumped out of his house to protest; he was last seen alive dragged away by militiamen. His corpse was found later, his hands handcuffed and his skull deformed, referred after Filipinas Photo Collection, [in:] Skyscrapercity forum, (link unavailable as blacklisted by Wikipedia)

- ^ perhaps he followed in the footsteps of his oldest brother Manuel, 17 years Antonio's senior; Manuel was engaged in requeté structures

- ^ as director of La Familia he advertised in a luxurious publication celebrating the centenary of Carlism, Roma 1933, p. 97

- ^ one press note contains a Carlist reference to a "Pérez de Olaguer", which might refer to him or to another member of the family, e.g. his oldest brother Manuel, El Siglo Futuro 08.01.34, available here

- ^ e.g. in 1934 Pérez de Olaguer was poking fun at Manuel Azaña, Gutierrez 01.09.34, available here

- ^ according to a source his oldest brother as Carlist requeté took part in the coup in Barcelona and died fighting for the university premises, El Progreso 06.11.36, available here. However, another source claims that he was not killed in combat but assassinated by the Republicans, and not during July 19-20th fightings but on July 26, 1936, César Alcalá, La represion politica en Catalunya (1936-1939), Madrid 2005, ISBN 8496281310, p. 135. According to Alcalá, the reason was a personal revenge of a former servant whose husband was killed in Asturias, La Razón 21.03.2009, available here. Another Antonio's brother, Their father was assassinated by the republican militia in Cornella in 1936, Enciclopedia universal ilustrada europeo-americana (Suplemento 1936 - 1939. 1.ª parte), Madrid 1944, p. 505.

- ^ it is not clear whether his pregnant wife and two young children fled with him or whether they had left Spain earlier. Anyway, his third son was born in 1936 in Genoa

- ^ El Progreso 06.11.36, available here

- ^ Filipinas Photo Collection, [in:] Skyscrapercity forum (link unavailable as blacklisted by Wikipedia)

- ^ the feast turned into a Carlist v. Falangist street fights and Fal Conde has to seek refuge in Pérez de Olaguer's house, Alcalá 2001, p. 52, Manuel Martorell Pérez, La continuidad ideológica del carlismo tras la Guerra Civil [PhD thesis in Historia Contemporanea, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia], Valencia 2009, p. 239

- ^ though he "realized a number of works for Junta Regional", Robert Vallverdú i Martí, La metamorfosi del carlisme català: del "Déu, Pàtria i Rei" a l'Assamblea de Catalunya (1936-1975), Barcelona 2014, ISBN 9788498837261, p. 107

- ^ some noted that serenity is the best word to describe his usual state of mind, La Vanguardia 30.03.68, available here

- ^ he is described as "afable i comprensiu", Vallverdú i Martí 2014, p. 127, "de actitud intachable",” Alcalá 2001, pp. 78-79

- ^ Vallverdú i Martí 2014, p. 107

- ^ Alcalá 2001, pp. 78-79

- ^ Pérez de Olaguer wrote: "lo que fundamentalmente necesita hoy España y la Comunión, o sea, un Jefé de Estado legitimo. fuerte, con continuidad institucional, bondad personal y institucional, y favorable situación internacional, y un caudillo monárquico y carlista que lleve al Carlismo a la lucha y, si Díos quiere, al triunfo", quoted after Alcalá 2001, pp. 79-80

- ^ Alcalá 2001, p. 93

- ^ in his May 1949 letter to Don Javier Pérez de Olaguer noted that Franco remains in power "por legítimo espíritu de conservación; porque sabe que en el momento que claudique y que ceda un palmo de terreno le espera la suerte de Hítler, de Mussolini, de Laval o de Quisling, sin que quiera por ello compararle con nadie, que es otra cosa", quoted after Martorell Pérez 2009, p. 324

- ^ he crafted the letter in his usual amicable manner, noting however that "los que con toda disciplina y lealtad, con absoluto desinterés y sacrificio, habíamos formado en las filas de Mauricio no merecíamos la patada", quoted after Vallverdú i Martí 2014, p. 115. The attempt was to no avail. Fal responded to him that dismissal was not premature but overdue, based on facts not calumnies, and so on, etc.

- ^ obedience to the claimant was the point of no-discussion for him, Vallverdú i Martí 2014, pp. 116-117

- ^ once Sivatte was dismissed his post went to Santiago Julia, who was from the onset appointed as a provisional caretaker, Vallverdú i Martí 2014, p. 126

- ^ eventually the Catalan jefatura went to Josep Puig i Pellicer. Vallverdú i Martí 2014, p. 126

- ^ Alcalá 2001, p. 99

- ^ Alcalá 2001, p. 110

- ^ and Francesco Puig and Eduardo Conde; the meeting took place in April 1956

- ^ Pérez de Olaguer was "personal friend of Don Javier and his host when in Barcelona", Alcalá 2001, p. 115. Don Javier argued that when corresponding with Pérez de Olaguer he enjoyed "facilidad de correspondencia que non tengo con los otros", Alcalá 2001, p. 116

- ^ Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El nuevo rumbo político del carlismo hacia la colaboración con el régimen (1955-56), [in:] Hispania 69 (2009), p. 193

- ^ Alcalá 2001, p. 120, Vázquez de Prada 2009, p. 194, Mercedes Vázquez de Prada, El final de una ilusión. Auge y declive del tradicionalismo carlista (1957-1967), Madrid 2016, ISBN 9788416558407, p. 43

- ^ compare case of 1958 homage to Pérez de Olaguer, attended by Sivatte, La Vanguardia 25.06.58, available here, La Vanguardia 28.06.58, available here, or the case of a common 1959 radio broadcast with Carlos Feliu de Travy, La Vanguardia 25.01.59, available here

- ^ he either steered clear of or maintained low profile during evidently Carlist events, e.g. he is not listed as attending homage to Antonio Domingo, whom he supported in municipal elections, La Vanguardia 04.12.63, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 16.06.45, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 14.12.45, available here, La Vanguardia 20.01.55, available here, La Vanguardia 27.05.56, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 08.11.49, available here

- ^ like Comisión de Fiestas de la Sagrada Familia, La Vanguardia 24.06.45, available here, or Organización de Refugiados Arabes de Tierra Santa, La Vanguardia 08.11.49, available here

- ^ Antonio Domingo Francas, La Vanguardia 30.10.63, available here

- ^ Ramón María Rodón Guinjoan. It is also revealing that when commending Rodón for his stand during a press interview, Pérez de Olaguer noted that "el Carlismo puede estar orgullose de usted". Ramón María Rodón Guinjoan, Invierno, primavera y otoño del carlismo (1939-1976) [PhD thesis Universitat Abat Oliba CEU], Barcelona 2015, p. 380

- ^ Daniel Jesús García Riol, La resistencia tradicionalista a la renovación ideológica del carlismo (1965-1973) [PhD thesis UNED], Madrid 2015, p. 99

- ^ Alcalá 2001, p. 166. Pérez de Olaguer was however conscious of enthusiasm that Don Carlos Hugo generated among the youth, acknowleding in a letter to Don Javier the crowds with "lealtad y de entusiasmo, singularmente por vuestro hijo Don Carlos Hugo, pero también por Vos", García Riol 2015, p. 99

- ^ Ensayos literarios were praised as written by a good observer but also by an author who lacked master command of the language, La Hormiga de Oro 07.01.26, available here. Commenting on De Occidente á Oriente por Suez the critics noted ease of writing and natural, jolly style, good prospective writer – Nuevo Mundo 01.03.29, available here. More than one reviewer noted that not many people of such a young age had the opportunity to travel that much, which produced an interesting literary blend, ABC 16.12.34, available here

- ^ La Hormiga de Oro 12.01.34, available here

- ^ ABC 20.08.33, available here

- ^ "unas peripecias novelescas, nos brinda tipos, de una moalculablo fuerza expresiva, que se agitan, conducen y manifiestan con ágil dinamismo y líneas morales caricaturescas de fresca originalidad", El Sol 15.04.32, available here

- ^ Contemporanea 9/III (1933), available here

- ^ El Sol 15.04.32m available here

- ^ La Hormiga de Oro 24.12.31, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 04.08.34, available here

- ^ in case of El canonigo Collell some noted that "puede decirse que toda la Cataluña de medio siglo XIX surge de nuevo a la vida", ABC 20.08.33, available here

- ^ though some complained about indulgence in dialogue and loose scenes, La Libertad 12.07.33, available here, La Vanguardia 09.07.33, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 21.10.35, available here

- ^ El Siglo Futuro 17.12.35, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 14.06.67, available here

- ^ La Vanguardia 23.05.51, available here

- ^ three volumes he published in 1950 were – according to the author – written to cheer people up, ABC 31.05.50, available here

- ^ compare e.g. Nuria Sabat, Pérez de Olaguer, una vida per al teatre, [in:] Revista de Girona 254 (2008), available here, Fons Gonzalo Pérez de Olaguer, [in:] Institut del Teatre service, available here, Marcos Ordónez, En la muerte de Gonzalo Pérez de Olaguer, crítico teatral, [in:] El País 04.06.08, available here, Mestre de teatre, [in:] El Punt Avui 03.06.08, available here, Joan Anton Benach, Decano de la critica teatral, [in:] La Vanguardia 03.07.08. available here, Gonzalo Pérez de Olaguer, [in:] ABC 04.06.08, available here

- ^ compare e.g. Santos Sanz Villanueva, Historia y crítica de la literatura española, vol. 8/1 (Epoca contemporanea 1939-1975), Barcelona 1999, ISBN 8474237815, Domingo Yndurain, Historia y critica de la literatura española 1939-1980, vol. 8 (Epoca contemporanea 1939-1980), Barcelona 1981, Jordi Gracia, Domingo Ródenas, Derrota y restitución de la modernidad: literatura contemporánea, 1939-2009, Madrid 2009, ISBN 9788498921229, Jean Canavaggio, Historia de la literatura española, vol. 6 (El siglo XX), Barcelona 1995, ISBN 843447459X

- ^ see e.g. Ignacio Soldevila Durante, Historia de la novela española 1936-2000, Madrid 2001, ISBN 8437619114

- ^ Santos Sanz Villanueva, La novela española durante el franquismo, Madrid 2010, ISBN 9788424904180, p. 316, Julio Rodríguez-Puértola, Historia de la literatura fascista española, vol. 2, Madrid 2008, ISBN 9788446029304, p. 1177, Piotr Sawicki, La narrativa española de la Guerra Civil (1936-1975). Propaganda, testimonio y memoria creativa, Alicante 2010, pp. 64, 138

- ^ Hugo García, Relatos para una guerra. Terror, testimonio y literatura en la España nacional, [in:] Ayer 76/4 (2009), pp. 153-154

- ^ Javier Rodrigo, Guerreros y teólogos. Guerra santa y martirio fascista en la literatura de la cruzada del 36, [in:] Hispania LXXIV/247 (2014), p. 571

- ^ "rusos, franceses y mejicanos ... comunistas, judios y masones" , García 2009, p. 165

- ^ they are depicted as embarking on a killing spree when enjoying themselves with tapas, beer and wine, García 2009, p. 166, Rodrigo 2014, p. 571

- ^ Javier Domínguez Arribas, El enemigo judeo-masónico en la propaganda franquista, 1936-1945, Madrid 2009, ISBN 9788496467989, pp. 243, 245, 259, 273, 284, 524

- ^ García 2009, p. 171

- ^ e.g. in Lágrimas y sonrisas discussing a certain Saturnino Lasterra from Artajona, who took part in the crusade of 1097, Pérez de Olaguer notes that "many years have passed. Even centuries have passed. The wheel of the Crusades keeps turning. There is now a heroic Crusade against unbridled communism. When the moment of truth came, Spain could not fail and the same is true of the land that produced Saturnino . . . and his small home town", quoted and translated after Francisco Javier Caspistegui, Spain's Vendee’: Carlist identity in Navarre as a mobilising model, [in:] Chris Ealham, Michael Richards (eds.), The Splintering of Spain, Cambridge 2005, ISBN 9780511132636, pp. 180-181

- ^ e.g. in Estampas Carlistas Pérez de Olaguer presented as typical a case of a village of which all males between 16 and 70 volunteered to requeté, Caspistegui 2005, pp. 187-188, see also Xosé Manoel Núñez Seixas, La España regional en armas y el nacionalismo de guerra franquista (1936-1939), [in:] Ayer 64/4 (2006), p. 210

- ^ Más leal que galante is according to one scholar "un acercamiento al pasado histórico, imperial, católico y hasta carlista, de España desde diferentes perspectivas, no sólo como recuperación de repertorio artístico, que fue, por lo general bastante deficiente, y esto en los casos en los que fue retomado, sino desde un punto de vista ideológico, esta vez totalmente divergente", Pablo García Blanco, Contra la placidez del pantano: teoría, crítica y práctica dramática de Gonzalo Torrente Ballester [PhD thesis, Universidad Carlos III de Madrid], Getafe 2008, p. 156

- ^ women were not supposed to fight and were reduced to auxiliary roles "because their fragile, delicate, loving fingers are not made for firing guns, but for weaving gentleness, applying honeyed gauzes to the wounds of those brave, heroic, marvellous Navarrese men", comments on Los de siempre by Caspistegui 2005, p. 186

- ^ e.g. Los de siempre is dismissed as "una antologia de cuentos escritos en un tono didáctico-moralizante que idealizan hasta los últimos extremos a los soldados carlistas y el sacrificio de la población de Navarra", Sawicki 2010, p. 64

- ^ compare La Tradició de Catalunya service, available here

- ^ compare Carlismo service, available here

- ^ there are exceptions; some scholars when quoting Perez de Olaguer refer simply to a "historiador", compare Julio Aróstegui, Combatientes Requetés en la Guerra Civil española, 1936-1939, Madrid 2013, ISBN 9788499709758, pp. 685, 708, 726, 750

- ^ Óscar J. Rodríguez Barreira, Poder y actitudes sociales durante la postguerra en Almería (1939-1953), Almeria 2007, ISBN 9788482408460, p. 253

- ^ Bruce Lincoln, Discourse and the Construction of Society. Comparative studies of Myth, Ritual and Classification, New York 2014, ISBN 9780199372362, Chapter 7, footnote 5 (page unavailable)

- ^ Maria Angharad Thomas, The Faith and the Fury: Popular Anticlerical Violence and Iconoclasm in Spain, 1931 – 1936 [PhD thesis Royal Holloway University of London], London 2012, p. 26

- ^ Peter C. Parsons, The Battle of Manila – Myth and Fact, s.l. 2013, p. 4, available here

Further reading[]

- César Alcalá, D. Mauricio de Sivatte. Una biografía política (1901-1980), Barcelona 2001, ISBN 8493109797

- Joan Maria Thomàs, Carlisme Barceloní als anys quarenta: „Sivattistes”, „Unificats”, „Octavistes”, [in:] L’Avenc 212 (1992), pp. 12–17

- Antonio Pérez de Olaguer, Mi padre, un hombre de bien, Sevilla 1967

- Javier Rodrigo, Guerreros y teólogos. Guerra santa y martirio fascista en la literatura de la cruzada del 36, [in:] Hispania LXXIV/247 (2014), pp. 555–586

- Piotr Sawicki, La narrativa española de la Guerra Civil (1936-1975). Propaganda, testimonio y memoria creativa, Alicante 2010

- Robert Vallverdú i Martí, La metamorfosi del carlisme català: del "Déu, Pàtria i Rei" a l'Assamblea de Catalunya (1936-1975), Barcelona 2014, ISBN 9788498837261

External links[]

- Carlists

- Spanish anti-communists

- Spanish monarchists

- Spanish Roman Catholics

- Spanish historians

- Roman Catholic writers

- Spanish dramatists and playwrights

- Spanish essayists

- Spanish male writers

- Spanish novelists

- 20th-century historians

- Male essayists

- Writers from Barcelona

- 1907 births

- 1968 deaths

- 20th-century essayists