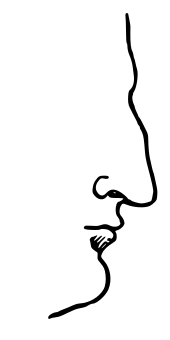

Aquiline nose

An aquiline nose (also called a Roman nose or Irish nose) is a human nose with a prominent bridge, giving it the appearance of being curved or slightly bent. The word aquiline comes from the Latin word aquilinus ("eagle-like"), an allusion to the curved beak of an eagle.[1][2][3] While some have ascribed the aquiline nose to specific ethnic, racial, or geographic groups, and in some cases associated it with other supposed non-physical characteristics (e.g., intelligence, status, personality, etc.), no scientific studies or evidence support any such linkage.

In racialist discourse[]

In racialist discourse, especially that of post-Enlightenment Western scientists and writers, a Roman nose has frequently been characterized as a marker of beauty and nobility,[4] as in Plutarch's description of Mark Antony.[5] The supposed science of physiognomy, popular during the Victorian era, made the "prominent" nose a marker of Aryanness: "the shape of the nose and the cheeks indicated, like the forehead's angle, the subject's social status and level of intelligence. A Roman nose was superior to a snub nose in its suggestion of firmness and power, and heavy jaws revealed a latent sensuality and coarseness".[6] In the twentieth century, proponents of scientific racism, such as Madison Grant[7] and William Z. Ripley, claimed the aquiline nose as characteristic of the peoples they variously identify as Nordic, Teutonic, Celtic, Norman, Frankish, and Anglo-Saxon.[8]

Among Native Americans[]

The aquiline nose was deemed a distinctive feature of some Native American tribes, members of which often took their names after their own characteristic physical attributes (e.g. The Hook Nose).[2] In the depiction of Native Americans, for instance, an aquiline nose is one of the standard traits of the "noble warrior" type.[9] It is so important as a cultural marker, Renee Ann Cramer argued in Cash, Color, and Colonialism (2005), that tribes without such characteristics have found it difficult to receive "federal recognition" or "acknowledgement" from the US government, which is necessary to have a continuous government-to-government relationship with the United States.[10]

See also[]

- Anatomy of the human nose

- Jewish nose

References[]

- ^ Cook, Eliza (1851). Eliza Cook's Journal. J. O. Clark. p. 381.

- ^ a b Fredriksen, John C. (1 January 2001). America's Military Adversaries: From Colonial Times to the Present. ABC-CLIO. p. 432. ISBN 978-1-57607-603-3.

He matured into a powerfully built man, tall, muscular, with an aquiline profile that gave rise to the name Woquni, or “Hook Nose.” The whites translated this into the more familiar moniker of Roman Nose. In his early youth, Roman Nose ...

- ^ Neuman, Henry; Baretti, Giuseppe Marco Antonio (1827). Neuman and Baretti's Dictionary of the Spanish and English Languages: Spanish and English. Hilliard, Gray, Little, and Wilkins. p. 65.

Aquiline, resembling an eagle; when applied to the nose, hooked.

- ^ Adams, Mikaëla M. (2009). "Savage Foes, Noble Warriors, and Frail Remnants: Florida Seminoles in the White Imagination, 1865-1934". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 87 (3): 404–35. JSTOR 20700234.

- ^ Jones, Prudence J. (2006). Cleopatra: A Sourcebook. U of Oklahoma P. p. 94. ISBN 9780806137414.

- ^ Cowling, Mary (1989). The Artist as Anthropologist: The Representation of Type and Character in Victorian Art. Cambridge. Cambridge UP. Quoted in McNees, Eleanor (2004). "Punch and the Pope: Three Decades of Anti-Catholic Caricature". Victorian Periodicals Review. 37 (1): 18–45. JSTOR 20083988.

- ^ Madison Grant, The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History (New York, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916), p. 31.

- ^ Winlow, Heather (2006). "Mapping Moral Geographies: W. Z. Ripley's Races of Europe and the United States". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 96 (1): 119–41. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.2006.00502.x. JSTOR 3694148. S2CID 145454002.

- ^ Cramer, Renee Ann (2006). "The Common Sense of Anti-Indian Racism: Reactions to Mashantucket Pequot Success in Gaming and Acknowledgment". Law & Social Inquiry. 31 (2): 313–41. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4469.2006.00013.x. JSTOR 4092749.

- ^ McCulloch, Anne M. (2006). "Rev. of Cramer, Cash, Color, and Colonialism". Perspectives on Politics. 4 (1): 178–79. doi:10.1017/s1537592706430140. JSTOR 3688655.

Further reading[]

- Barolsky, Paul (2007). Michelangelo's Nose: A Myth and Its Maker. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9780271032726.

- Biological anthropology

- Facial features

- Nose