Archaeology of Afghanistan

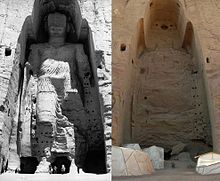

Archaeology of Afghanistan, mainly conducted by British and French antiquarians, has had a heavy focus on the treasure filled Buddhist monasteries that lined the silk road from the 1st c. BCE – 6th c. AD. Particularly the ancient civilizations in the region during the Hellenistic period and the Kushan Empire.[1] The world's oldest-known oil paintings, dating to the 7th c. AD, were found in caves in Afghanistan's Bamiyan Valley.[2] The valley is also home to the famous Buddhas of Bamiyan which were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001.

History of archeology in Afghanistan[]

Early 19th century marked the first archaeological investigation, both excavation and recording of historic sites in Afghanistan.[3] This work was commenced mainly after the British Indian Army officers travelled through the mainland and uncovered the treasures of Afghanistan's ancient history. Their inexhaustible curiosity and ability to amass raw archaeological information led to many significant discoveries and laid foundations for modern scientific archaeology.[3]

Two of these many investigation efforts deserve attention. During the period of antiquity, a British envoy by the name of James Lewis abandoned his post for the British East India Company at Agra in 1827 and headed north-east under the alias of Charles Masson.[4] His three-year travels would take him through Northern India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan and he would later record detailed accounts of his travels for the Bombay Government in the Masson Bombay Dispatches in 1834.[5] This British antiquarian is also known to have surveyed and excavated a significant number of Buddhist artifacts around Kabul and Jalalabad alongside his discoveries from ancient Kapisa, Kushan capital of Begram in the 1st–3rd centuries C.E. The 30,000 coins he recovered during these excavations play a large role in defining the basis of Greco-Bactrain, Indo-Parthian, and Kushan numismatic history of Afghanistan.[3] Most of the treasures and artifacts that Lewis recovered were sent to the British Museum in London where most are housed today.

Further archeological research would not be conducted in the region until the French signed a 30-year contract with a newly independent Afghanistan in 1921–22. This contract established Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan (DAFA), giving the exclusive right of archeological research in the nation to France.[6] This agreement was renewed until 1978, not without revisions, and detailed accounts of the research conducted under this agreement can be found in the 32 volumes of the Mémoires des Délégation Archéologique Française en Afghanistan. One clause of the agreement states that all archeological findings, except for gold, were to be divided evenly between France and Afghanistan until 1965 when all findings would be declared property of Afghanistan. Archeological materials collected by DAFA were sent to the Afghanistan National Museum in Kabul and the Museé national des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet in Paris.

Archaeological research under DAFA traced the prosperous societies along the silk road mainly focusing on the Buddhist monasteries of the Kushan and Hellenistic periods. Full-scale excavations began in Hadda in 1926 by French Archaeologist, Barthoux. He recovered over 15,000 artifacts and fragments from eight monasteries and 500 stupas that were divided between Kabul and Paris.[7] The world-renowned Buddhas of Bamiyan are the most well-known artifacts from the Bamiyan Valley for being the largest standing Buddhas in the world and for their recent destruction by the Taliban. However, Bamiyan is also home to the famous Begram glasses and ivories that were uncovered by another French Archeologist, Hackin, in 1937.[8] The French monopoly of archeology began to erode in the mid 19th century as Afghanistan began archeological collaborations with nations such as Italy, Germany, Japan, India, U.K., U.S., and the U.S.S.R. Research came to a halt as a result of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 and has been slow to resume due to the instability of the region. Afghanistan has suffered civil wars and its conflict with the Taliban persists into the present day.

The Afghan Institute of Archaeology was established in 1966 which attracted the attention of many foreign missions and resulted in important discoveries post-Second World War. This institute also allowed for significant number of research by Afghans themselves.[3] Ahmad-'Ali Kohzad of the Historical Society of Afghanistan (Anjoman-e Tarik-e Afghnestan, q.v.) surveyed portions of central Afghanistan while Shahibiya Mostamandi and Zemaryalai Tarzi initiated full scale excavations at Hadda (Tepe Sotor).

Destruction of artifacts[]

During the Soviet-Afghan War archeological sites like the ones at Hadda were leveled and many of the artifacts were destroyed. Looting was also rife during this conflict and continued through the civil wars that broke out after Soviets withdrew their forces in 1989, into the present day with ongoing conflict in the region. The Taliban, under orders of Mullah Mohammed Omar in 2001, called for the destruction of the famous Buddhas of Bamiyan and they were reduced to rubble. Stability has been brought back to the Bamiyan Valley today and the historic Buddhas have been returned to their original stature as 3D light projections.

References[]

- ^ Stark, Miriam T. (2005). Archaeology of Asia. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 335. ISBN 978-1405102131.

- ^ "World's oldest oil paintings in Afghanistan". Reuters. 22 April 2008. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- ^ a b c d "EXCAVATIONS". Encyclopaedia Iranica Online. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ "MASSON, Charles – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Errington, Elizabeth Jane (2001). "Charles Masson and Begram". Topoi. Orient-Occident. 11 (1): 357–409. doi:10.3406/topoi.2001.1941.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Rediscovering the Past - Two Centuries of Archaeology". www.cemml.colostate.edu. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Rediscovering the Past - Two Centuries of Archaeology". www.cemml.colostate.edu. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ Errington, Elizabeth Jane (2001). "Charles Masson and Begram". Topoi. Orient-Occident. 11 (1): 357–409. doi:10.3406/topoi.2001.1941.

External links[]

- Archaeology of Afghanistan

- Afghan history stubs

- Asian archaeology stubs