Aromanians

Armãnji, Rrãmãnji | |

|---|---|

The flag most commonly associated with the Aromanians, unofficial but with traditional roots | |

| Total population | |

| c. 250,000 (Aromanian-speakers)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 39,855 (1951 census)[2][obsolete source] estimated up to 200,000 | |

| 26,500 (2006 estimate)[3] | |

| 9,695 (2002 census)[4] | |

| 8,266 (2011 census)[5] estimated up to 200,000 | |

| (2011 census)[6] | |

| 243 (2011 census)[7][8] | |

| 29 (2011 census)[9] | |

| 13 (2002 census)[10] | |

| 10 (2013 census)[11] | |

| Languages | |

| Aromanian | |

| Religion | |

| Eastern Orthodox Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Romance peoples; (most notably Romanians, Moldovans, Megleno-Romanians, and Istro-Romanians) | |

| Part of a series on |

| Aromanians |

|---|

|

|

| By region or country |

| Major settlements |

| Language and identity |

| Religion |

|

| History |

|

| Related groups |

|

The Aromanians (Aromanian: Armãnji, Rrãmãnji)[12] are a Romance[13] ethnic group native to the Balkans, traditionally living in Serbia, North Macedonia, Montenegro, northern and central Greece, central and southern Albania and south-western Bulgaria, and currently to be found in central and southern Albania, south-western Bulgaria, south-western North Macedonia, northern and central Greece, southern Serbia and south-eastern Romania (Dobruja). The Aromanians are also known by several names, such as "Vlachs" or "Macedo-Romanians"[14][15][16] (sometimes used to also refer to the Megleno-Romanians).[17]

The term "Vlachs" is used in Greece to refer to Aromanians, but this term is internationally used to encompass all Romance-speaking peoples of the Balkans and Tatra Mountains regions.[18]

Aromanians speak the Aromanian language, a Latin-derived vernacular very similar to Romanian, which has many slightly varying dialects of its own.[19] It descends from the Vulgar Latin spoken by the Paleo-Balkan peoples (Latinised Thracians or Dacians for example) subsequent to their Romanization. Aromanian is a mix of Latin and post-Big Migrations domestic language with additional influences from other surrounding languages of the Balkans, mainly Greek, Albanian, Macedonian, and Bulgarian.[20]

Names and classification

Ethnonyms

The term Aromanian derives directly from the Latin Romanus, meaning Roman citizen. The initial a- is a regular epenthetic vowel, occurring when certain consonant clusters are formed, and it is not, as folk etymology sometimes has it, related to the negative or privative a- of Greek (also occurring in Latin words of Greek origin). The term was coined by Gustav Weigand in his 1894 work Die Aromunen. The first book to which many scholars have referred to as the most valuable to translate their ethnic name is a grammar printed in 1813 in Austria by . The Greek title was Grammatike Romanike Etoi Makedono-Blachike (Roman or Macedono-Vlach Grammar).

The terms Vlach is an exonym; used since medieval times. Aromanians call themselves Rrãmãn or Armãn, depending on which of the two dialectal groups they belong, and identify as part of the Fara Armãneascã ("Aromanian tribe") or the Populu Armãnescu ("Aromanian people").[12] The endonym is rendered in English as Aromanian, in Romanian as Aromâni, in Greek as Armanoi (Αρμάνοι), in Albanian as Arumunët, in Bulgarian as Arumani (Арумъни), in Macedonian as Aromanci (Ароманци), in Serbo-Croatian as Armani and Aromuni.

The term "Vlach" was used in medieval Balkans as an exonym for all the Romance-speaking (Romanized) people of the region, as well as a general name for shepherds, but nowadays is commonly used for the Aromanians and Meglenites, Daco-Romanians[21] being named Vlachs only in Serbia, Bulgaria and North Macedonia. The term is noted in the following languages: Greek "Vlachoi" (Βλάχοι), Albanian "Vllah", Bulgarian, Serbian and Macedonian "Vlasi" (Bласи), Turkish "Ulahlar", Hungarian[22] "Oláh". It is noteworthy that the term Vlach also meant "bandit" or "rebel" in Ottoman historiography, and that the term was also used as an exonym for mainly Orthodox Christians in Ottoman-ruled western Balkans (mainly denoting Serbs), as well as by the Venetians for the immigrant Slavophone population of the Dalmatian hinterland (also mainly denoting Serbs).

Groups

German academic Thede Kahl divides the Aromanians into two main groups, the "Rrãmãnji" and "Armãnji", which are further divided into sub-groups.[12]

Rrãmãnji

- Muzăchiars, from Muzachia situated in southwestern-central Albania.

- Fãrshãrots (or Fãrshãriots), concentrated in Epirus, from Frashër (Aromanian Farshar), once Aromanian urban centre situated in south-eastern Albania.

- Moscopolitans or Moscopoleans, from the city of Moscopole, once an important urban center of the Balkans, now a village in southeastern Albania.

Armãnji

- Pindeans, concentrated in and around the Pindus Mountains of Northern and Central Greece.

- Gramustians (or Gramosteans, gr. grammostianoi), from Gramos Mountains, an isolated area in south-eastern Albania, and north-west of Greece.

Nicknames

The Aromanian communities have several nicknames depending on the country where they are living.

- Gramustians and Pindians are nicknamed Koutsovlachs (Greek: Κουτσόβλαχοι). This term is sometimes taken as derogatory, as the first element of this term is from the Greek koutso- (κουτσό-) meaning "lame". Following a Turkish etymology where küçük means "little" they are the smaller group of Vlachs as opposed to the more numerous Vlachs (Daco-Romanians).

- Farsherots, from Frashër (Albania), Moscopole and Muzachia are nicknamed "Frashariotes" or Arvanitovlachs (Greek Αρβανιτόβλαχοι), meaning "Albanian Vlachs" referring to their place of origin.[23] Most of the Frashariotes are characterized also as "Greek-Vlach Northern Epirotes" because of their frequent historical inhabitancy of ethnic Greek territory.[24]

In the South Slavic countries, such as Serbia, North Macedonia and Bulgaria, the nicknames used to refer to the Aromanians are usually Vlasi (South Slavic for Vlachs and Wallachians) and Tsintsari (also spelled Tzintzari, Cincari or similar), which is derived from the way the Aromanians pronounce the word meaning five, tsintsi. In Romania, the demonym Macedoni, Machedoni or Macedoromâni is also used. In Albania, the terms Vllah ("Vlach") and Çoban or Çobenj (from Turkish çoban, "shepherd") are used.[25]

Population

Settlements

The Aromanian community in Albania is estimated up to 200,000 people, including those who no longer speak the language.[26] Tanner estimates that the community constitutes 2% of the population.[26] In Albania, Aromanian communities inhabit Moscopole, their most famous settlement, the Kolonjë District (where they are concentrated), a quarter of Fier (Aromanian Ferãcã), while Aromanian was taught, as recorded by Tom Winnifrith, at primary schools in Andon Poçi near Gjirokastër (Aromanian Ljurocastru), Shkallë (Aromanian Scarã) near Sarandë, and Borovë near Korçë (Aromanian Curceau) (1987).[23]

A Romanian research team concluded in the 1960s that Albanian Aromanians migrated to Tirana, Stan Karbunarë, Skrapar, Pojan, Bilisht and Korçë, and that they inhabited Karaja, Lushnjë, Moscopole, Drenovë (Aromanian Dãrnova) and Boboshticë (Aromanian Bubushtitsa).[23] There was an important community of Aromanians in Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina that was probably assimilated by local dwellers. Initially they were Christians but around year 1000 they adhered to Bogomil/Patarene Christian sect and were Serbianized. After the Turkish occupation, the Aromanians of Bosnia and Herzegovina converted to Islam faith due to economic and religious motifs.[27] There are many artifacts of Aromanians in Bosnia and Herzegovina, mainly in their necropolises. These necropolises cover all Bosnia and consist of funerary monuments, generally without crosses.

Origin

The Aromanian language is related to the Vulgar Latin spoken in the Balkans during the Roman period.[28] It is hard to establish the history of the Vlachs in the Balkans, with a gap between the barbarian invasions and the first mentions of the Vlachs in the 11th and 12th centuries.[29] Byzantine chronicles are unhelpful, and only in the 13th, 14th and 15th centuries the term Vlach becomes more frequent, although it proves problematic to distinguish sorts of Vlachs as it was used for various subjects, such as the empire of the Asen dynasty, Thessaly, and Romania across the Danube.[29] It has been assumed that Aromanians are descendants of Roman soldiers or Latinized original populations (Greeks, Illyrians, Thracians or Dardanians), due to the historical Roman military presence in the territory inhabited by the community.[28] Many Romanian scholars maintain that the Aromanians were part of a Daco-Romanian migration from the north of the Danube between the 6th[30] and 10th centuries, supporting the theory that the 'Great Romanian' population descend from the ancient Dacians and Romans.[31] Greek scholars view the Aromanians as descendants of Roman legionaries that married Greek women.[30] There is no evidence for either theory, and Winnifrith deems them improbable.[30] The little evidence that exists points that the Vlach (Aromanian) homeland was in the southern Balkans and North of the Jireček Line demarcating the Latin and Greek linguistic influence spheres.[32] With the Slavic breakthrough of the Danube frontier in the 7th century, Latin-speakers were pushed further southwards.[32]

History and self-identification

The Aromanians or Vlachs first appear in medieval Byzantine sources in the 11th century, in the Strategikon of Kekaumenos and Anna Komnene's Alexiad, in the area of Thessaly.[33] In the 12th century, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela records the existence of the district of "Vlachia" near Halmyros in eastern Thessaly, while the Byzantine historian Niketas Choniates places "Great Vlachia" near Meteora. Thessalian Vlachia was apparently also known as "Vlachia in Hellas".[34] Later medieval sources also speak of an "Upper Vlachia" in Epirus, and a "Little Vlachia" in Aetolia-Acarnania, but "Great Vlachia" is no longer mentioned after the late 13th century.[33]

The medieval Vlachs (Aromanians) of Herzegovina are considered authors of the famous funerary monuments with petroglyphs (stecci in Serbian) from Herzegovina and surrounding countries. The theory of the Vlach origin was proposed by Bogumil Hrabak (1956) and Marian Wenzel[35] and more recently was supported by the archeological and anthropological researches of skeleton remains from the graves under stećci. The theory is much older and was first proposed by Arthur Evans in his work Antiquarian Researches in Illyricum (1883). While doing research with Felix von Luschan on stećak graves around Konavle, he found that a large number of skulls were not of Slavic origin but similar to older Illyrian and Arbanasi tribes, as well as noting that Dubrovnik memorials recorded those parts inhabited by the Vlachs until the 15th century.[36]

Aromanians within the Balkan nationalisms of the 19th and 20th centuries

A distinct Aromanian consciousness was not developed until the 19th century, and was influenced by the rise of other national movements in the Balkans.[37]

Until then, the Aromanians, as Eastern Orthodox Christians, were subsumed with other ethnic groups into the wider ethnoreligious group of the "Romans" (in Greek Rhomaioi, after the Eastern Roman or Byzantine Empire), which in Ottoman times formed the distinct Rum millet.[38] The Rum millet was headed by the Greek-dominated Patriarchate of Constantinople, and the Greek language was used as a lingua franca among Balkan Orthodox Christians throughout the 17th–19th centuries. As a result, wealthy, urbanized Aromanians were culturally Hellenized and played a major role in the dissemination of Greek language and culture; indeed, the first book written in Aromanian was written in the Greek alphabet and aimed at spreading Greek among Aromanian-speakers.[39]

By the early 19th century, however, the distinct Latin-derived nature of the Aromanian language began to be studied in a series of grammars and language booklets.[40] In 1815, the Aromanians of Budapest requested permission to use their language in liturgy, but it was turned down by the local metropolitan.[40]

The establishment of a distinct Aromanian national consciousness, however, was hampered by the tendency of the Aromanian upper classes to be absorbed in the dominant surrounding ethnicities, and espouse their respective national causes as their own.[41] So much did they become identified with the host nations that Balkan national historiographies portray the Aromanians as the "best Albanians", "best Greeks" and "best Bulgarians", leading to researchers calling them the "chameleons of the Balkans".[42] Consequently, many Aromanians played a prominent role in the modern history of the Balkan nations: the revolutionary Pitu Guli, Greek Prime Minister Ioannis Kolettis, Greek magnate Georgios Averoff, Greek Defence Minister Evangelos Averoff, Serbian Prime Minister Vladan Đorđević, Patriarch Athenagoras I of Constantinople, Romanian metropolitan Andrei Şaguna, the Wallachian and Moldavian rulers of the Ghica family, etc.

Following the establishment of independent Romania and the autocephaly of the Romanian Orthodox Church in the 1860s, the Aromanians increasingly began to come under the influence of the Romanian national movement. Although vehemently opposed by the Greek church, the Romanians established an extensive state-sponsored cultural and educative network in the southern Balkans: the first Romanian school was established in 1864, and by the early 20th century there were 100 Romanian churches and 106 schools with 4,000 pupils and 300 teachers.[43] As a result, Aromanians divided into two main factions, one pro-Greek, the other pro-Romanian, plus a smaller focusing exclusively on its Aromanian identity.[38]

With the support of the Great Powers, and especially Austria-Hungary, the "Aromanian-Romanian movement" culminated in the recognition of the Aromanians as a distinct millet (the Ullah Millet) by the Ottoman Empire on 22 May 1905, with corresponding freedoms of worship and education in their own language.[44] Nevertheless, due to the advanced assimilation of the Aromanians, this came too late to lead to the creation of a distinct Aromanian national identity; indeed, as Gustav Weigand noted in 1897, most Aromanians were not only indifferent, but actively hostile to their own national movement.[45]

At the same time, the Greek–Romanian antagonism over Aromanian loyalties intensified with the armed Macedonian Struggle, leading to the rupture of diplomatic relations between the two countries in 1906. During the Macedonian Struggle, most Aromanians participated on the "patriarchist" (pro-Greek) side, but some sided with the "exarchists" (pro-Bulgarians).[44] However, following the Balkan Wars of 1912–13, Romanian interest waned, and when it revived in the 1920s it was designed more towards encouraging the Romanians' "Macedonian brothers" to emigrate to Southern Dobruja, where there were strong non-Romanian minorities.[45]

While Romanian activity declined, from World War I on and with its involvement in Albania, Italy made some efforts—not very successful—in converting pro-Romanian sympathies into pro-Italian ones.[45] In World War II, during the Axis occupation of Greece, Italy encouraged Aromanian nationalists to form an "Aromanian homeland", the so-called Principality of the Pindus. The project never gained much traction among the local population, however. On the contrary, many leading figures of the Greek Resistance against the Axis, like Andreas Tzimas, Stefanos Sarafis, and Alexandros Svolos, were Aromanians. The "principality" project collapsed with the Italian armistice in 1943.

Modern Aromanian identities

The date of the announcement of the Ottoman irade of 23 May 1905 has been adopted in recent times by Aromanians in Albania, Australia, Bulgaria and North Macedonia as the "Aromanian National Day" (Dzua Natsionalã a Armãnjilor), but notably not in Greece or among the Aromanians in the Greek diaspora.[46]

In modern times, Aromanians generally have adopted the dominant national culture, often with a dual identity as both Aromanian and Greek/Albanian/Bulgarian/Macedonian/Serbian/etc.[47] Aromanians are also found outside the borders of Greece. There are many Aromanians in southern Albania and in towns all over the Balkans,[46] while Aromanians identifying as Romanians are still to be found in areas where Romanian schools were active.[47] There are also many Aromanians who identify themselves as solely Aromanian (even, as in the case of the "Cincars", when they no longer speak the language). Such groups are to be found in southwestern Albania, the eastern parts of North Macedonia, the Aromanians who immigrated to Romania in 1940, and in Greece in the Veria (Aromanian Veryea or Veryia) and Grevena (Aromanian Grebini) areas and in Athens.[46]

Culture

Religion

The Aromanians are predominantly Orthodox Christians, and follow the Eastern Orthodox liturgical calendar.

Cuisine

One of the most well-known Aromanian foods which as main dishes are pisurudã (home made noodles fried in oil or grease), pisurudã (lardon, well-fried bacon), tigãnjauã which are pieces of fried pork in a pan, ahnii (meat dish with vegetables usually with potatoes or beans or onions), pãstrãmã (the Aromanian version of pastirma), etc. Hence the Aromanian cuisine is mainly focused around meat, lard and animal fat. Lãrdii is a type of pork fat used for cooking and usãndzã is a type of pork fat & bacon. Tigane is an Aromanian fried type of donut. Aromanian cuisine is also centered around pies as well such as brushtulã which is a cheese and butter style pie, cãmbãcuchi which is an Aromanian cake or pie made of corn flour, cãtsãroanje an Aromanian pita-pie made of many leaves, with the top one being flaky and curly, pitã di lapti (literally "milk pie") and many more.

Music

The polyphonic song of Epirus is a form of traditional folk polyphony practiced among Aromanians, Albanians, Greeks and Macedonians in southern Albania and northwestern Greece. The polyphonic song of Epirus is not to be confused with other varieties of polyphonic singing, such as the yodeling songs of the region of Muotatal, or the Cantu a tenore of Sardinia.

Clothing

In Aromanian rural areas, clothes differed from the dress of the city dwellers. The shape and the colour of a garment, the volume of the headgear, the shape of a jewel could indicate cultural affiliation and also could show the village people came from. Fustanella usage among Aromanians can be traced to at least the 15th century, with notable examples being seen in the Aromanian stećak of the Radimlja necropolis. Additionally Aromanians claim the fustanella as their ethnic costume.

Aromanians today

In Greece

In Greece, Aromanians are not recognised as an ethnic but as a linguistic minority and, like the Arvanites, have been indistinguishable in many respects from other Greeks since the 19th century.[48][49] Although Greek Aromanians would differentiate themselves from native Greeks (Grets) when speaking in Aromanian, most still consider themselves part of the broader Greek nation (Elini, Hellenes), which also encompasses other linguistic minorities such as the Arvanites or the Slavic speakers of Greek Macedonia.[50] Greek Aromanians have long been associated with the Greek national state, actively participated in the Greek Struggle for Independence, and have obtained very important positions in government,[51] although there was an attempt to create an autonomous Aromanian canton under the protection of Italy at the end of World War I, called Principality of the Pindus. Aromanians have been very influential in Greek politics, business and the army. Revolutionaries Rigas Feraios and Giorgakis Olympios,[52] Prime Minister Ioannis Kolettis,[53] billionaires and benefactors Evangelos Zappas and Konstantinos Zappas, businessman and philanthropist George Averoff, Field Marshal and later Prime Minister Alexandros Papagos, and conservative politician Evangelos Averoff[54] were all either Aromanians or of partial Aromanian heritage. It is difficult to estimate the exact number of Aromanians in Greece today. The Treaty of Lausanne of 1923 estimated their number between 150,000 and 200,000, but the last two censuses to differentiate between Christian minority groups, in 1940 and 1951, showed 26,750 and 22,736 Vlachs respectively.[50] Estimates on the number of Aromanians in Greece range between 40,000[2] and 300,000. Kahl estimates the total number of people with Aromanian origin who still understand the language as no more than 300,000, with the number of fluent speakers under 100,000.[50]

The majority of the Aromanian population lives in northern and central Greece; Epirus, Macedonia and Thessaly. The main areas inhabited by these populations are the Pindus Mountains, around the mountains of Olympus and Vermion, and around the Prespa Lakes near the border with Albania and the Republic of North Macedonia. Some Aromanians can still be found in isolated rural settlements such as Samarina (Aromanian Samarina, Xamarina or San Marina), Perivoli (Aromanian Pirivoli) and Smixi (Aromanian Zmixi). There are also Aromanians (Vlachs) in towns and cities such as Ioannina (Aromanian Ianina, Enina or Enãna), Metsovo (Aromanian Aminciu), Veria (Aromanian Veryia) Katerini, Trikala (Aromanian Trikolj), Grevena (Aromanian Grebini) and Thessaloniki (Aromanian Sãruna)

Generally, the use of the minority languages has been discouraged in Greece,[55] although recently there have been efforts to preserve the endangered languages (including Aromanian) of Greece.

Since 1994, the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki offers beginner and advanced courses in "Koutsovlach", and cultural festivals with over 40,000 participants—the largest Aromanian cultural gatherings in the world—regularly take place in Metsovo.[56] Nevertheless, there are no exclusively Aromanian newspapers, and the Aromanian language is almost totally absent from television.[56] Indeed, although as of 2002 there were over 200 Vlach cultural associations in Greece, many did not even feature the term "Vlach" in their titles, and only a few are active in preserving the Aromanian language.[56]

In 1997, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe passed a resolution encouraging the Balkan states to take steps to rectify the "critical situation" of Aromanian culture and language.[57] In response, the then President of Greece, Konstantinos Stefanopoulos, publicly urged Greek Aromanians to teach the language to their children.

In 2001, 31 Aromanian mayors and heads of villages signed a protest resolution against the U.S. State Department report on the human rights situation in Greece. They complained "against the direct or indirect characterisation of the Vlach-speaking Greeks as an ethnic, linguistic or other minority, stating that the Vlach-speaking Greeks never requested to be recognised by the Greek state as a minority, stressing that historically and culturally they were and still are an integral part of Hellenism, they would be bilingual and Aromanian would be secondary".[58]

Furthermore, the largest Aromanian group in Greece (and across the world), the Panhellenic Federation of Cultural Associations of Vlachs in Greece,[56] has repeatedly rejected the classification of Aromanian as a minority language or the Vlachs as a distinct ethnic group separate from the Greeks, considering the Aromanians as an "integral part of Hellenism".[59][60][61] The Aromanian (Vlach) Cultural Society, which is associated with Sotiris Bletsas, is represented on the Member State Committee of the European Bureau for Lesser Spoken Languages in Greece.[62]

In Albania

There is a large Aromanian community in Albania, which is officially called Vlach Minority (Albanian: Minoriteti Vllah), specifically in the southern and central regions of the country. It is estimated that the number of Aromanians in Albania go up to 200,000, including those not speaking the language any more.[63][64] There are currently timid attempts to establish education in their native language in the town of Divjakë.[65]

For the last years there seems to be a renewal of the former policies of supporting and sponsoring of Romanian schools for Aromanians of Albania. As a recent article in the Romanian media points out, the kindergarten, primary and secondary schools in the Albanian town of Divjakë where the local Albanian Aromanians pupils are taught classes both in Aromanian and Romanian were granted substantial help directly from the Romanian government. The only Aromanian language church in Albania is the Transfiguration of Jesus (Aromanian Ayiu Sutir) of Korçë, which was given 2 billion lei help from the Romanian government. They also have a political party named Aleanca për Barazi dhe Drejtësi Europiane (The Alliance for European Equality and Justice), and two social organisations named Shoqata Arumunët/Vllehtë e Shqiperisë (The Society of the Aromanians/Vlachs of Albania) and Unioni Kombëtar Arumun Shqiptar (The Aromanian Albanian National Union). Many of the Albanian Aromanians (Arvanito Vlachs) have immigrated to Greece, since they are considered in Greece part of the Greek minority in Albania.[66]

Notable Aromanians whose family background hailed from today's Albania include Bishop Andrei Şaguna, and Reverend , whereas notable Albanians with an Aromanian family background are actors Aleksandër (Sandër) Prosi, Margarita Xhepa, Albert Vërria, and , as well as composer Nikolla Zoraqi[67] and singers Eli Fara and Parashqevi Simaku.

On 13 October 2017, Aromanians received the official status of ethnic minority, through voting of a bill by Albanian Parliament.

In North Macedonia

According to official government figures (census 2002), there are 9,695 Aromanians or Vlachs, as they are officially called in North Macedonia. According to the census of 1953 there were 8,669 Vlachs, 6,392 in 1981 and 8,467 in 1994.[68] Aromanians are recognized as an ethnic minority, and are hence represented in Parliament and enjoy ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious rights and the right to education in their language.

There are Aromanian cultural societies and associations such as the Union for Aromanian Culture from North Macedonia, The Aromanian League of North Macedonia, The International League of Aromanians, Comuna Armãneascã "Frats Manachi", (The Aromanian Community Manaki Brothers) in Bitola (Aromanian Bituli or Bitule), Partia a'Armãnjlor di tu Machedonia (The Party of the Aromanians from Macedonia) and Unia Democraticã a'Armãnjlor di tu Machedonia (The Democratic Union of the Aromanians from Macedonia).

Many forms of Aromanian-language media have been established since the 1990s. North Macedonia's Government provides financial assistance to Aromanian-language newspapers and radio stations. Aromanian-language newspapers such as (Aromanian: Fenix) service the Aromanian community. The Aromanian television program Spark (Aromanian: Scanteao; Macedonian Искра (Iskra)) broadcasts on the second channel of the Macedonian Radio-Television.

There are Aromanian classes provided in primary schools and the state funds some Aromanian published works (magazines and books) as well as works that cover Aromanian culture, language and history. The latter is mostly done by the first Aromanian Scientific Society, "Constantin Belemace" in Skopje (Aromanian Scopia), which has organized symposiums on Aromanian history and has published papers from them. According to the last census, there were 9,596 Aromanians (0.48% of the total population). There are concentrations in Kruševo (Aromanian Crushuva) 1,020 (20%), Štip (Aromanian Shtip) 2,074 (4.3%), Bitola 1,270 (1.3%), Struga 656 (1%), Sveti Nikole (Aromanian San Nicole) 238 (1.4%), Kisela Voda 647 (1.1%) and Skopje 2,557 (0.5%).[4]

In Romania

Since the Middle Ages, due to the Turkish occupation and the destruction of their cities, such as Moscopole, Gramoshtea, Linotopi and later on Kruševo, many Aromanians fled their native homelands in the Balkans to settle the Romanian principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, which had a similar language and a certain degree of autonomy from the Turks. These immigrant Aromanians were assimilated into the Romanian population.

In 1925, 47 years after Dobruja was incorporated into Romania, King Ferdinand gave the Aromanians land and privileges to settle in this region, which resulted in a significant migration of Aromanians into Romania. Today, 25% of the population of the region are descendants of Aromanian immigrants.[citation needed]

There are currently between 50,000 and 100,000 Aromanians in Romania, most of which are concentrated in Dobruja.[citation needed] According to the Union for Aromanian Language and Culture, there are some 100,000 Aromanians in Romania, and they are often called macedoni ("Macedonians").[citation needed] Some Aromanian associations even place the total number of people of Aromanian descent in Romania as high as 250,000.[citation needed]

Recently,[when?] there has been a growing movement in Romania, both by Aromanians and by Romanian lawmakers, to recognize the Aromanians either as a separate cultural group or as a separate ethnic group, and extend to them the rights of other minorities in Romania, such as mother-tongue education and representatives in parliament.[citation needed]

In Bulgaria

Most of the Aromanians in the Sofia region are descendants of Macedonian and northern Greek emigrants who arrived between 1850 and 1914.[69]

In Bulgaria, most Aromanians were concentrated in the region south-west of Sofia, in the region called Pirin, formerly part of the Ottoman Empire until 1913. Due to this reason, a large number of these Aromanians moved to Southern Dobruja, part of the Kingdom of Romania after the Treaty of Bucharest of 1913. After the reinclusion of Southern Dobruja in Bulgaria with the Treaty of Craiova of 1940, most were moved to Northern Dobruja in a population exchange. Another group moved to northern Greece. Nowadays, the largest group of Aromanians in Bulgaria is found in the southern mountainous area, around Peshtera. Most Aromanians in Bulgaria originate from the Gramos Mountains, with some from North Macedonia, the Pindus Mountains in Greece and Moscopole in Albania.[70]

After the fall of communism in 1989, Aromanians and Romanians (known as "Vlachs" in Bulgaria) have started initiatives to organize themselves under one common association.[71][72][73]

According to the 1926 official census, there were 69,080 Romanians, 5,324 Aromanians, 3,777 Cutzovlachs, and 1,551 Tsintsars.[citation needed]

In Serbia

In medieval times, the Aromanians populated Herzegovina and elevated famous necropolises with petroglyphs (Radimlja, Blidinje, etc.).[74] The Aromanians, known as Cincari (Цинцари), migrated to Serbia in the 18th and early 19th centuries. They most often were bilingual in Greek, and were often called "Greeks" (Grci). They were influential in the forming of Serbian statehood, having contributed with rebel fighters, merchants and intellectuals. Many Greek Aromanians (Грко Цинцари) came to Serbia with Alija Gušanac as krdžalije (mercenaries) and later joined the Serbian Revolution (1804–1817). Some of the notable rebels include Konda Bimbaša and Papazogli.[75] Among the notable people of Aromanian descent are playwright Jovan Sterija Popović (1806–1856), novelist Branislav Nušić (1864–1938), and politician Vladan Đorđević (1844–1930).

The majority of Serbian people of Aromanian descent do not speak Aromanian and espouse a Serb identity. They live in Niš, Belgrade and some smaller communities in Southern Serbia, such as Knjaževac. The Lunjina Serbian–Aromanian Association was founded in Belgrade in 1991. According to the 2011 census, there were 243 Serbian citizens that identified as ethnic Cincari.[76] However, unofficial estimates number the Aromanian population of Serbia at 5,000[77]–15,000.[78]

Diaspora

Aside from the Balkan countries, there are also communities of Aromanian emigrants living in Canada, the United States, France and Germany. Although the largest diaspora community is in select major Canadian cities, Freiburg, Germany has one of the most important Aromanian organisations, the Union for Culture and Language of the Aromanians, and one of the largest libraries in the Aromanian language. In the United States, the Society Farsarotul is the oldest and most well-known association of Aromanians, founded in 1903 by Nicolae Cican, an Aromanian native of Albania. In France, the Aromanians are grouped in the Trã Armãnami ("for Aromanians") cultural association.[79]

Genetic studies

In 2006 Bosch et al. attempted to determine if the Aromanians are descendants of Latinised Dacians, Greeks, Illyrians, Thracians or a combination of these, but it was shown that they are genetically indistinguishable from the other Balkan populations. Linguistic and cultural differences between Balkan groups were deemed too weak to prevent gene flow among the groups.[80]

- Y-DNA haplogroups[80]

| Sample population | Sample size | R1b | R1a | I | E1b1b | E1b1a | J | G | N | T | L | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aromanians from Dukas, Albania[80] | 39 | 2.6% (1/39) | 2.6% (1/39) | 17.9% (7/39) | 17.9% (7/39) | 0.0 | 48.7% (19/39) | 10.3% (4/39) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Aromanians from Andon Poçi, Albania[80] | 19 | 36.8% (7/19) | 0.0 | 42.1% (8/19) | 15.8% (3/19) | 0.0 | 5.3% (1/19) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Aromanians from Kruševo, North Macedonia[80] | 43 | 27.9% (12/43) | 11.6% (5/43) | 20.9% (9/43) | 20.9% (9/43) | 0.0 | 11.6% (5/43) | 7.0% (3/43) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Aromanians from Štip, North Macedonia[80] | 65 | 23.1% (15/65) | 21.5% (14/65) | 16.9% (11/65) | 18.5% (12/65) | 0.0 | 20.0% (13/65) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |

| Aromanians in Romania[80] | 42 | 23.8% (10/42) | 2.4% (1/42) | 19.0% (8/42) | 7.1% (3/42) | 0.0 | 33.3% (14/42) | 0.0 | — | — | — | – 14.4% (6/42) |

| Aromanians in Balkan Peninsula | 39+ 19+ 43+ 65+ 42= 208 |

21.63% (45/208) | 10.1% (21/208) | 20.67% (43/208) | 16.35% (34/208) | 0.0 | 25% (52/208) | 3.37% (7/208) | — | — | — | – 2.9% (6/208) |

Haplogroup R1b is the most common haplogroup among two or three of the five tested Aromanian populations, which is not shown as a leading mark of the Y-DNA locus in other regions or ethnic groups on the Balkan Peninsula. On the 16 Y-STR markers from the five Aromanian populations, Jim Cullen's predictor speculates that over half of the mean frequency of 22% R1b of the Aromanian populations is more likely to belong to the L11 branch.[80]> L11 subclades form the majority of Haplogroup R1b in Italy and western Europe, while the eastern subclades of R1b are prevailing in populations of the eastern Balkans.[81]

Notable Aromanians

This section does not cite any sources. (December 2020) |

Art and literature

- Alexandru Arsinel—comedian and actor

- Constantin Belimace—poet

- Ion Luca Caragiale—playwright, short story writer, poet, theater manager, political commentator and journalist

- Toma Caragiu—theatre, television and film actor

- Konstantin Čomu—cinema operator

- Elena Gheorghe—singer

- Jovan Četirević Grabovan—icon painter

- Stere Gulea—film director and screenwriter

- Kira Hagi—actress

- Dimitrios Lalas—composer and musician

- Taško Načić—actor

- Sergiu Nicolaescu—film director, actor and politician

- Constantin Noica—philosopher, essayist and poet

- Branislav Nušić—playwright, satirist, essayist, novelist

- Dan Piţa—film director and screenwriter

- Aurel Plasari—writer

- Jovan Sterija Popović—playwright, poet, lawyer, philosopher and pedagogue

- Florica Prevenda—painter

- Toše Proeski—singer

- Sandër Prosi—actor

- Camil Ressu—painter and academic

- Konstantinos Tzechanis—philosopher, mathematician and poet

- Nuși Tulliu—poet and prose writer

- Albert Vërria—actor

- Lika Yanko—painter

- Jovan Jovanović Zmaj—poet

Law, philanthropy and commerce

- George Averoff—businessman and philanthropist

- Gigi Becali—businessman and politician

- Emanoil Gojdu—lawyer

- Petar Ičko—merchant

- Mocioni family—barons, philanthropists and bankers

- Theodoros Modis—lumber merchant and scholar

- Sterjo Nakov—businessman

- Simon Sinas—banker, aristocrat, benefactor and diplomat

- Georgios Sinas—entrepreneur, banker and national benefactor

- Michael Tositsas—benefactor

- Evangelis Zappas—philanthropist and businessman

- Konstantinos Zappas—entrepreneur and national benefactor

Military

- Konda Bimbaša—fighter

- Pitu Guli—revolutionary

- Christodoulos Hatzipetros—military leader

- Anastasios Manakis—revolutionary

- Giorgakis Olympios—military commander

- Alexandros Papagos—army officer[82]

- Anastasios Pichion—educator and fighter

- Stefanos Sarafis—army officer

- Konstantinos Smolenskis—army officer

- Leonidas Smolents—army officer

- Mitre the Vlach—revolutionary

Politics

- Apostol Arsache—politician and philanthropist

- Evangelos Averoff—politician and writer

- Nicolae Constantin Batzaria—politician, activist and writer

- Marko Bello—politician, diplomat and lecturer

- Yannis Boutaris—politician and businessman

- Costică Canacheu—politician and businessman

- Ion Caramitru—politician and actor

- Alcibiades Diamandi—politician

- Michael Dukakis—politician

- Vladan Đorđević—politician, diplomat, physician, prolific writer, organizer of the State Sanitary Service

- Rigas Feraios—writer, political thinker and revolutionary

- Taki Fiti—politician

- Ştefan Octavian Iosif—poet and translator

- Ioannis Kolettis—politician

- Helena Angelina Komnene

- Spyridon Lambros—politician and professor

- Apostol Mărgărit—writer

- Nicolaos Matussis—politician

- Georgios Modis—jurist, politician and writer

- Alexandros Papagos— politician and army officer

- Pilo Peristeri—politician

- Dan Stoenescu—diplomat, political scientist and journalist

- Alexandros Svolos—politician

- Andreas Tzimas—politician

- Petros Zappas—entrepreneur and politician

Religion

- Cyril of Bulgaria—patriarch

- Joachim III of Constantinople—ecumenical patriarch

- Theodore Kavalliotis—priest and teacher

- Andrei Șaguna—metropolitan bishop

- Nektarios Terpos—scholar and monk

Sciences, academia and engineering

- Sotiris Bletsas

- Elie Carafoli

- Ioannis Chalkeus

- Sterie Diamandi

- Neagu Djuvara

- Jovan Karamata

- Mina Minovici

- Theodore Modis

- Yorgo Modis

- Daniel Moscopolites

- George Murnu

- Pericle Papahagi

- Nicolae Malaxa

Sports

- Gheorghe Hagi—football coach and former player

- Ianis Hagi—football player

- Simona Halep—tennis player

- Keidi Bare—football player

- Cristian Gaţu—handball player

- —boxer

- —boxer

- Dominique Moceanu—gymnast

- Gert Trasha—weightlifter

- Theoharis Trasha—weightlifter

Gallery

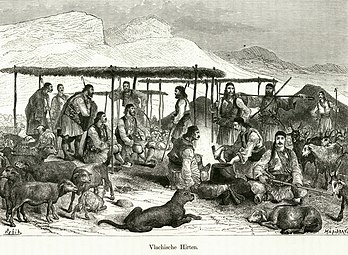

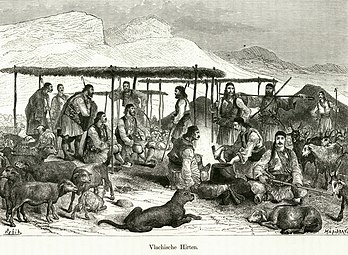

Vlach (Aromanian) herdsmen in Greece (Amand Schweiger from Lerchenfeld, 1887)

Aromanian men of Macedonia, circa 1914

Kutsovlachs in 1915

See also

- Romanians

- Megleno-Romanians

- Istro-Romanians

- Vlachs

- Thraco-Roman

Citations

- ^ Puig, Lluis Maria de (17 January 1997). "Report: Aromanians". Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly. Doc. 7728.

- ^ Jump up to: a b According to INTEREG – quoted by Eurominority Archived 3 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine: Aromanians in Greece Archived 19 May 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Gatej, Iuliana (8 December 2006). "Aromânii vor statut minoritar". Cotidianul (in Romanian). Archived from the original on 9 March 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "North Macedonia census 2002" (PDF). Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ "Albanian census 2011" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 November 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ "2011 Bulgaria Census". Censusresults.nsi.bg. 2011. Archived from the original on 19 December 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ "Попис становништва, домаћинстава и станова 2011. у Републици Србији" (PDF) (in Serbian). Statistics of Serbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "Third Report Submitted by Serbia Pursuant to Article 25, Paragraph 2 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities". Council of Europe. pp. 14–15. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "1. Population by Ethnicity – Detailed Classification, 2011 Census". Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- ^ "Popis 2002". Statistics of Slovenia. Retrieved 31 July 2019.

- ^ "1. Stanovništvo prema etničkoj/nacionalnoj pripadnosti – detaljna klasifikacija". Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kahl 2002, p. 145.

- ^ Minahan, James (2000). One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 776. ISBN 978-0313309847.

Romance (Latin) nations...

- ^ Benevedes, Eli; Lally, Owen; Li, Hung-En; Perlee, Abigail; Piombino, Eileen (2021). Investigating the Impacts of Earthquakes on Ethnic and Religious Groups: Bucharest, Romania (PDF) (Thesis). Worcester Polytechnic Institute. pp. 1–63.

- ^ Tudorancea, Radu (2007). "An analysis of the Macedo-Romanian issue within the Romanian–Greek relations during the first decade of the twentieth century (1900–1926)" (PDF). Euro-Atlantic Studies (11): 91–97.

- ^ Vrabie, Emil (1993). "Aromanian etymologies". General Linguistics. 33 (4): 212–219. ProQuest 1301510711.

- ^ Țîrcomnicu, Emil (2009). "Some topics of the traditional wedding customs of the Macedo–Romanians (Aromanians and Megleno–Romanians)". Romanian Journal of Population Studies. 3 (3): 141–152.

- ^ "Vlach – European ethnic group". Britannica.com. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 March 2006. Retrieved 16 May 2006.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ James Minahan (1 January 2002). Encyclopedia of the Stateless Nations: A-C. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 175–. ISBN 978-0-313-32109-2. Retrieved 18 April 2012.

- ^ "What does Daco-Romanian mean?". www.definitions.net.

- ^ "Magyar Néprajzi Lexikon /". Mek.niif.hu. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Winnifrith 1987, p. 35.

- ^ Katsanis, N.A.; Dinas, K.D. "Ch. 6. The names of the Vlachs". The Vlachs of Greece (in Greek).

Στην Αλβανία υπάρχουν οι Φρασαριώτες Βλάχοι (από την περιοχή Φράσαρι) γνωστοί και ως Αρβανιτόβλαχοι, οι περισσότεροι από τους οποίους είναι Ελληνόβλαχοι βορειοηπειρώτες που κατά καιρούς, λόγω των ιστορικών συνθηκών, εγκαθίστανται στον ελληνικό χώρο.

- ^ Tanner 2004, pp. 203–.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tanner 2004, p. 209.

- ^ Isidor Ieşan, Secta patarenă în Balcani şi în Dacia Traiană. Institutul de arte grafice C. Sfetea, București, 1912

- ^ Jump up to: a b Tanner 2004, p. 210.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Winnifrith 1987, p. 39.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Winnifrith 2002, p. 114.

- ^ Tanner 2004, p. 205.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Winnifrith 2002, p. 115.

- ^ Jump up to: a b ODB, "Vlachs" (A. Kazhdan), pp. 2183–2184.

- ^ ODB, "Vlachia" (A. Kazhdan), p. 2183.

- ^ Marian Wenzel, Bosnian and Herzegovinian Tombstobes-Who Made Them and Why?" Sudost-Forschungen 21(1962): 102–143

- ^ Mužić, Ivan (2009). "Vlasi i starobalkanska pretkršćanska simbolika jelena na stećcima". Starohrvatska prosvjeta (in Croatian). Split: Museum of Croatian Archaeological Monuments. III (36): 315–349.

- ^ "BJUNIORNEWBLOG: THE AROMANIAN REBIRTH". 11 September 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kahl 2002, p. 146.

- ^ Kahl 2002, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kahl 2002, p. 147.

- ^ Kahl 2002, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Kahl 2002, p. 150.

- ^ Kahl 2002, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kahl 2002, p. 148.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kahl 2002, p. 149.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kahl 2002, p. 151.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kahl 2002, p. 152.

- ^ Elisabeth Kontogiorgi, Population exchange in Greek Macedonia the rural settlement of refugees 1922–1930, p. 22

- ^ Viktor Meier (1999). Yugoslavia: A History of Its Demise. Routledge. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-415-18596-7.

The problem of the linguistic minorities in Greece is a complex one ... They both consider themselves Greeks

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Kahl 2002, p. 153.

- ^ John S. Koliopoulos, Plundered loyalties Axis occupation in Greek West Macedonia 1941–1949, pages 81–85

- ^ Leontis, Artemis (2009). Culture and customs of Greece. Greenwood Press. p. 13. ISBN 9780313342967.

- ^ Merry, Bruce (2004). Encyclopedia of modern Greek literature. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 163. ISBN 9780313308130.

- ^ Brown, James F. (2001). The grooves of change: Eastern Europe at the turn of the millennium. Duke University Press. p. 261. ISBN 9780822326526.

- ^ Greek Monitor of Human and Minority Rights vol I. No 3 December 1995

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Kahl 2002, p. 155.

- ^ "Recommendation 1333 (1997) on the Aromanian culture and language". 1997. Archived from the original on 18 November 2002. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ Kahl 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Έκδοση ψηφίσματος διαμαρτυρίας κατά του Στέτ Ντιπαρτμεντ (in Greek). 28 February 2001. Archived from the original on 15 September 2004. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ Έκδοση Δελτίου Τύπου για την διοργάνωση του Συνεδρίου του Ελληνικού παραρτήματος της μη κυβερνητικής οργάνωσης του Ε.Β.L.U.L., στη Θεσσαλονίκη (in Greek). 14 November 2002. Archived from the original on 10 September 2004. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ Έκδοση ψηφίσματος διαμαρτυρίας κατά της έκθεσης της Αμερικανικής οργάνωσης Freedom House (in Greek). 18 August 2003. Archived from the original on 15 September 2004. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- ^ "Learn a Foreign Language". eblul.org.[dead link]

- ^ Tanner 2004, p. 208.

- ^ Winnifrith 1995.[incomplete short citation]

- ^ "Aromanians in Albania" (PDF). Ecmi.de. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers. The Albanian Aromanians´ Awakening: Identity Politics and Conflicts in Post-Communist Albania Archived 18 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine, p. 12-13.

- ^ Çollaku, Robert (July–August 2011). Gusho, Jani (ed.). "Frația (Vëllazëria)". Calendaru 2011. Arumunët e Shqipërisë. p. 2.

- ^ The Vlachs of Macedonia Archived 27 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Tom J. Winnifrith.

- ^ Conseil de l'Europe. Assemblée parlementaire. Session ordinaire (1997). Documents de séance. Council of Europe. p. xxi. ISBN 978-92-871-3239-0.

- ^ Армъните в България ("The Aromanians in Bulgaria") (in Bulgarian). Архитектурно-етнографски комплекс "Етър" – Габрово. Archived from the original on 30 January 2009. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ^ "Ministerul Afacerilor Externe". MAE.ro. 23 July 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ "Lumea Magazin". 5 September 2005. Archived from the original on 5 September 2005.

- ^ "Romanian Global News – singura agentie de presa a romanilor de pretutindeni". 7 October 2007. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 9 January 2018.

- ^ Marian Wenzel, Bosnian and Herzegovinian Tombstobes-Who Made Them and Why?" Sudost-Forschungen 21(1962): 102–143.

- ^ Mitološki zbornik. 7–8. Centar za mitološki studije Srbije. 2002. p. 35.

Многи Грко-Цинцари су дошли у Србију са Гушанцем као крхалије, па су касније пришли устаницима. У ову групу спадају Конда и Папазоглија. У Гушанчевој војсци Конда је био буљубаша, све до 1806. године, када су устаници ...

- ^ ""Остали" етничке заједнице са мање од 2000 припадника и двојако изјашњени" (PDF). RZS. 2012 [2011]. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ Jokić Stamenković, Dragana (30 January 2017). "Цинцари – крвоток Балкана". Politika (in Serbian).

- ^ Ružica, Miroslav (2006). "The Balkan Vlachs/Aromanians awakening, national policies, assimilation". Proceedings of the Globalization, Nationalism and Ethnic Conflicts in the Balkans and Its Regional Context: 28–30. S2CID 52448884.

- ^ "TRA ARMANAMI » Aestu site".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Bosch, E.; Calafell, F.; González-Neira, A.; Flaiz, C; Mateu, E; Scheil, HG; Huckenbeck, W; Efremovska, L; et al. (2006). "Paternal and maternal lineages in the Balkans show a homogeneous landscape over linguistic barriers, except for the isolated Aromuns". Annals of Human Genetics. 70 (Pt 4): 459–87. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2005.00251.x. PMID 16759179. S2CID 23156886.

- ^ Myres, Natalie M. (2010). "A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b Holocene era founder effect in Central and Western Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 19 (1): 95–101. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.146. PMC 3039512. PMID 20736979.

- ^ Jovanovski, Dalibor; Minov, Nikola (2017). "Ioannis Kolettis. The Vlach from the ruling elite of Greece". Balcanica Posnaniensia. Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. 24 (1): 222–223. ISSN 2450-3177. Retrieved 8 May 2017.

General sources

- Atanassova, Katya (1998). "Aromanians". Communities and Identities in Bulgaria: 1000–1012.

- Cozaru, G. C., A. C. Papari, and M. L. Sandu. "Considerations Regarding the Ethno-Cultural Identity of the Aromanians in Dobrogea". Tradition and Reform Social Reconstruction of Europe (2013): 121.

- Iosif, Corina (2011). "The Aromanians between nationality and ethnicity: the history of an identity building". Transylvanian Review. 20: 133–148.

- Kahl, Thede (2002). "The Ethnicity of Aromanians after 1990: the Identity of a Minority that Behaves like a Majority". Ethnologia Balkanica. 6. pp. 145–169.

- Kahl, Thede (2003). "Aromanians in Greece. Minority or Vlach-Speaking Greeks?". Jahrbücher für Geschichte und Kultur Südosteuropas. 5: 205–219.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- Kocój E., Heritage without Heirs? Tangible and religious cultural heritage of the Vlachs minority in Europe in the context of interdisciplinary research project (contribution to the subject), Balcanica Posnaniensia", Poznań 2015, s. 137–147.

- Kocój E., The Story of an Invisible City. The Cultural Heritage of Moscopole in Albania. Urban Regeneration, Cultural Memory and Space Management [in:] Intangible heritage of the city. Musealisation, preservation, education, ed. By M. Kwiecińska, Kraków 2016, s. 267–280.

- Kocój E., Artifacts of the past as traces of memory. The Aromanian cultural heritage in the Balkans, Res Historica, 2016, p. 175–195.

- Motta, Giuseppe (2011). "The Fight for Balkan Latinity. The Aromanians until World War I". Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. 2 (3): 252–260.

- Motta, Giuseppe (2012). "The Fight for Balkan Latinity (II). The Aromanians after World War". Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. 3 (11): 541–550.

- Nowicka, E. (2016). "Ethnic Identity of Aromanians/Vlachs in the 21st Century". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Ruzica, Miroslav (2006). "The Balkan Vlachs/Aromanians Awakening, National Policies, Assimilation" (PDF). Proceedings of the Globalization, Nationalism and Ethnic Conflicts in the Balkans and Its Regional Context. Belgrade. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- Schwandner-Sievers, Stephanie (1999). "The Albanian Aromanians' awakening: identity politics and conflicts in post-communist Albania". Flensburg: European Centre for Minority Issues. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Tanner, Arno (2004). "The Vlachs—A contested identity". The Forgotten Minorities of Eastern Europe: The History and Today of Selected Ethnic Groups in Five Countries. East-West Books. pp. 203–. ISBN 978-952-91-6808-8.

- Ţîrcomnicu, Emil (2009). "Some Topics of the Traditional Wedding Customs of the Macedo–Romanians (Aromanians and Megleno–Romanians)". Romanian Journal of Population Studies Supplement. 3 (Supplement): 141–152.

- Winnifrith, Tom (1987). The Vlachs: the history of a Balkan people (PDF). Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-7156-2135-6.

- Winnifrith, Tom (2002). "Vlachs". In Clogg, Richard (ed.). Minorities in Greece: Aspects of a Plural Society. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 112–121. ISBN 978-1-85065-705-7.

Further reading

- "Report: The Vlachs". Greek Monitor of Human & Minority Rights. 1 (3). December 1995 [May–June 1994].

- Gica, Alexandru. The recent history of the Aromanians in Southeast Europe. Scr/bd. Rome, 2010 (The Recent History of the Aromanians in Southeast Europe-Alexandru Gica | Republic Of Macedonia | Greece)

External links

Media related to Aromanians at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Aromanians at Wikimedia Commons

- Aromanians

- Eastern Romance people

- Ethnic groups in Albania

- Ethnic groups in Bulgaria

- Ethnic groups in Greece

- Ethnic groups in North Macedonia

- Ethnic groups in Romania

- Ethnic groups in Serbia

- Ethnic groups in the Balkans

- Romance peoples

- Ethnic groups divided by international borders