Arthur Scherbius

Arthur Scherbius | |

|---|---|

Arthur Scherbius, inventor of the Enigma cipher. | |

| Born | 30 October 1878 |

| Died | 13 May 1929 (aged 50) |

| Nationality | German |

| Education | Technical University Munich & Leibniz University Hannover, PhD in Engineering |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Engineering career | |

| Significant design | Enigma machine |

Arthur Scherbius (30 October 1878 – 13 May 1929) was a German electrical engineer who invented the mechanical cipher Enigma machine.[1] He patented the invention and later sold the machine under the brand name Enigma.

Scherbius offered unequalled opportunities and showed the importance of cryptography to both military and civil intelligence.

Biography[]

Early life and work[]

Scherbius was born in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. His father was a businessman.

He studied electrical engineering at the Technical University Munich and then went on to study at the Leibniz University Hannover, finishing in March 1903. The next year he completed a dissertation entitled "Proposal for the Construction of an Indirect Water Turbine Governor" and was awarded a doctorate in engineering (Dr.-Eng.).

Career[]

Scherbius subsequently worked for a number of electrical firms in Germany and Switzerland. In 1918 he founded the firm of Scherbius & Ritter. He made a number of inventions including asynchronous motors, electric pillows and ceramic heating parts. His research contributions led to his name being associated with the for asynchronous motors.

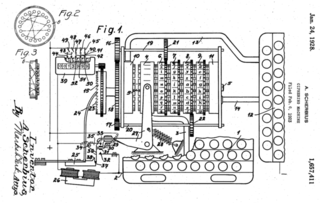

Scherbius applied for a patent (filed 23 February 1918) for a cipher machine based on rotating wired wheels that is now known as a rotor machine.

The Enigma machine[]

His first design of the Enigma was called Model A and was about the size and shape of a cash register (50 kg). Then followed Model B and Model C, which was a portable device in which the letters were indicated by lamps. The Enigma machine looked like a typewriter in a wooden box.

He called his machine Enigma which is the Greek word for "riddle". Combining three rotors from a set of five, each of the 3 rotor setting with 26 positions, and the plug board with ten pairs of letters connected, the military Enigma has 158,962,555,217,826,360,000 (nearly 159 quintillion) different settings. (5 × 4 × 3) × (263) × [26! / (6! × 10! × 210)] = 158,962,555,217,826,360,000.

The firm's cipher machine, marketed under the name "Enigma", was initially pitched at the commercial market. There were several commercial models; one of them was adopted by the German Navy (in a modified version) in 1926. The German Army adopted the same machine (also in a modified version somewhat different from the Navy's) a few years later.

Scherbius initially had to contend with the lack of interest in his invention, but he was convinced that his Enigma would be marketable. However the German Army did become interested in a new cryptographic device despite several disappointments in the past. The serial production of the Enigma started in 1925 and the first machines came into use in 1926.

Scherbius' Enigma provided the German Army with one of the strongest cryptographic ciphers at the time. German military communications were protected using Enigma machines during World War II until they were eventually cracked by Bletchley Park due to a fatal flaw in the encryption algorithm whereby characters were never encrypted as themselves.

Scherbius however did not live to see the widespread use of his machine. In 1929, Scherbius died in a horse carriage accident in Berlin-Wannsee, where he had lived since 1924.

Impact[]

In “Turing’s Cathedral” George Dyson states “…a cryptographic machine had been invented by the German electrical engineer Arthur Scherbius, who proposed it to the German navy, an offer that was declined. Scherbius then founded the Chiffriermaschinen Aktiengesellschaft to manufacture the machine, under the brand name Enigma, for enciphering commercial communications, such as transfers between banks. The German navy changed its mind and adopted a modified version of the Enigma machine in 1926, followed by the German army in 1928, and the German air force in 1935”.[2]

Patents[]

References[]

Notes[]

- ^ Friedrich L. Bauer (2006). Decrypted Secrets: Methods and Maxims of Cryptology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 111. ISBN 9783662040249.

- ^ Dyson, George (2012). Turing's Cathedral. Pantheon. Chapter 13. ISBN 9780307907066.

Bibliography[]

- David Kahn, Seizing the Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-Boats Codes, 1939–1943 (Houghton Mifflin 1991) (ISBN 978-0-395-42739-2)

- 1878 births

- 1929 deaths

- Technical University of Munich alumni

- University of Hanover alumni

- Cipher-machine cryptographers

- German information theorists

- German logicians

- 20th-century German inventors

- 20th-century German mathematicians

- Businesspeople from Frankfurt