Attacks on Serbs during the Serbian–Ottoman War (1876–1878)

The events of persecution against the Serbian population occurred in Ottoman Kosovo in 1878, as a consequence of the Serbian–Ottoman War (1876–78).[1] Incoming Albanian refugees to Kosovo who were expelled by the Serb army from the Sanjak of Niš were involved in revenge attacks and hostile to the local Serb population.[2][3][4] Ottoman Albanian troops also participated in attacks, at the behest of Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II.[1]

Background[]

During the Serbian–Ottoman War of 1876–78, between 30,000 and 70,000 Muslims, mostly Albanians, were expelled by the Serb army from the Sanjak of Niš and fled to the Kosovo Vilayet.[5][6][7][8][9][4] Within the context of the Serbian–Ottoman War, the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II unleashed his auxiliary troops consisting of Kosovar Albanians on the remaining Serbs before and after the Ottoman army's retreat in 1878.[10] Tensions in the form of revenge attacks arose by incoming Albanian refugees on local Kosovo Serbs that contributed to the beginnings of the ongoing Serbian-Albanian conflict in coming decades.[2][3][4]

1878[]

January 18–19[]

With the Serbian capture of Niš, the Kumanovo villagers awaited the Serbian Army which went for Vranje and Kosovo.[11] The Serbian artillery fire was heard throughout the winter of 1877/78.[11] Ottoman Albanian troops from Debar and Tetovo fled the front and crossed the Pčinja, looting and raping along the way.[11]

On January 18, 1878, 17 armed Albanians descended from the mountains into Oslare, shouting while entering the village.[11] They first arrived at the house of Arsa Stojković, which they looted and emptied before his eyes, enraging Stojković who proceeded to punch one of them.[11] He was shot in the stomach and fell down, though still alive, he took a stake and delivered a mighty blow to the shooter's head, dying with him.[11] The villagers then quickly entered an armed fight with the Albanians, killing them.[11]

On January 19, 1878, 40 Albanian deserters retreating from the Ottoman army broke into the house of elder Taško, a serf, in the Bujanovac region, tied up the males and raped his two daughters and two daughters-in-law,[12] then proceeded to loot the house and left the village.[11] Taško armed himself and persuaded the village to retaliate, tracing them in the snow and multiplying in numbers.[13] The Albanian deserters were dispersed, drunk, and were intercepted first at Lukarce, where 6 of them were beaten to death.[13] They killed all of them.[12]

With the taste of blood, revenge and victory, the retaliation grew into an uprising, with the avengers becoming rebels, riding armed on horse as soldiers, through the villages of Kumanovo and Kriva Palanka and called to revolt.[13] The movement was strengthened by Mladen Piljinski and his group's killing of Ottoman Albanian haramibaşı Bajram Straž and his seven friends, whose severed heads were brought as trophies and used as flags in the villages. On January 20, 1878, the leaders of the Kumanovo Uprising were chosen.[13]

January 26[]

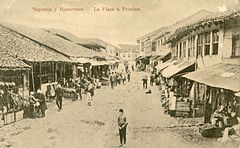

Downtown Pristina. | |

| Date | January 26–27, 1878 |

|---|---|

| Location | Panađurište hamlet, Pristina, Ottoman Empire (now Kosovo) |

| Cause | Advance of the Serbian Army |

| Participants | Albanians |

| Deaths | Numerous Serbs murdered, as well as Albanian attackers |

| Property damage | Houses set on fire |

At the same time, there was a massacre of Serbs in Pristina by armed Albanians who took advantage of the anarchy and confusion that followed.[13] On January 26, refugees from Albanian-inhabited villages came to Pristina with news that Serbian outposts were already at Gračanica.[13] Albanians started attacking Serb houses, and robbed, kidnapped, beat and killed people.[14]

Armed Albanians gathered in the Serb-inhabited mahala of Panađurište,[15] where most of the atrocities took place.[16][17] Five men knocked on the door of gunmaker Jovan Janićijević (known as Jovan Đakovac).[14] Jovan was a friend of the Serbian teacher Kovačević in Pristina.[16] As no one opened, in order to cross the wall, three stood on each other.[18] Jovan shot the one peeking into the yard, and the house was riddled with shots, and Jovan's wife was killed.[18] Jovan took his children and broke the wall to his neighbour's house, a friend who was a Turk, and pushed them through the wall.[18] His relative Stojan shot back, halting their attack.[18] Jovan and Stojan defended themselves, while half a day passed with attacks and victims.[18] The attackers left the premises through the Četiri Lule Street, then returned with hay and straws and set the house on fire, which was filled by smoke.[18] Stojan surrendered on the promise of besa, however, he was decapitated, and his head was thrown on the street.[18] Jovan, the only one left, entered the basement when the house broke down.[18] With a shoulder wound, he rushed out the field and managed to shoot three of the attackers, before being killed.[18] They marched the Pristina bazaar with his head on a pole.[19]

For the 20 dead Albanians, they demanded redemption in blood; just one of the houses, of Hadži-Kosta, gave 17 victims.[19] In the night, when fatigue and hunger stopped the massacre, the askeri counted the dead.[19]

Legacy[]

Ottoman defeat to Serbia alongside new geopolitical circumstances post 1878 opposed by Albanian nationalists resulted in anti-Christian attitudes among them that eventually supported what today is known as "ethnic cleansing" that made part of the Kosovo Serb population to leave.[20]

Prior to the Balkan wars (1912–13), Kosovo Serb community leader Janjićije Popović stated that the wars of 1876–1878 "tripled" the hatred of Turks and Albanians, especially that of the refugee population from the Sanjak of Niš toward Serbs by committing acts of violence against them.[4]

References[]

- ^ a b Lampe, 2000, p. 55.

- ^ a b Frantz, Eva Anne (2009). "Violence and its Impact on Loyalty and Identity Formation in Late Ottoman Kosovo: Muslims and Christians in a Period of Reform and Transformation". Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs. 29 (4): 460–461. doi:10.1080/13602000903411366. "In consequence of the Russian-Ottoman war, a violent expulsion of nearly the entire Muslim, predominantly Albanian-speaking, population was carried out in the sanjak of Niš and Toplica during the winter of 1877-1878 by the Serbian troops. This was one major factor encouraging further violence, but also contributing greatly to the formation of the League of Prizren. The league was created in an opposing reaction to the Treaty of San Stefano and the Congress of Berlin and is generally regarded as the beginning of the Albanian national movement. The displaced persons (Alb. muhaxhirë, Turk. muhacir, Serb. muhadžir) took refuge predominantly in the eastern parts of Kosovo. The Austro-Hungarian consul Jelinek reported in April of 1878.... The account shows that these displaced persons (muhaxhirë) were highly hostile to the local Slav population.... Violent acts of Muslims against Christians, in the first place against Orthodox but also against Catholics, accelerated. This can he explained by the fears of the Muslim population in Kosovo that were stimulated by expulsions of large Muslim population groups in other parts of the Balkans in consequence of the wars in the nineteenth century in which the Ottoman Empire was defeated and new Balkan states were founded. The latter pursued a policy of ethnic homogenisation expelling large Muslim population groups."; p. 467. "Clewing (as well as Müller) sees the expulsions of 1877 – 1878 as a crucial reason for the culmination of the interethnic relations in Kosovo and 1878 as the epoch year in the Albanian-Serbian conflict history."

- ^ a b Müller, Dietmar (2009). "Orientalism and Nation: Jews and Muslims as Alterity in Southeastern Europe in the Age of Nation-States, 1878–1941". East Central Europe. 36 (1): 63–99. doi:10.1163/187633009x411485. "For Serbia the war of 1878, where the Serbians fought side by side with Russian and Romanian troops against the Ottoman Empire, and the Berlin Congress were of central importance, as in the Romanian case. The beginning of a new quality of the Serbian-Albanian history of conflict was marked by the expulsion of Albanian Muslims from Niš Sandžak which was part and parcel of the fighting (Clewing 2000 : 45ff.; Jagodić 1998 ; Pllana 1985). Driving out the Albanians from the annexed territory, now called "New Serbia," was a result of collaboration between regular troops and guerrilla forces, and it was done in a manner which can be characterized as ethnic cleansing, since the victims were not only the combatants, but also virtually any civilian regardless of their attitude towards the Serbians (Müller 2005b). The majority of the refugees settled in neighboring Kosovo where they shed their bitter feelings on the local Serbs and ousted some of them from merchant positions, thereby enlarging the area of Serbian-Albanian conflict and intensifying it."

- ^ a b c d Stefanović, Djordje (2005). "Seeing the Albanians through Serbian eyes: The Inventors of the Tradition of Intolerance and their Critics, 1804–1939". European History Quarterly. 35 (3): 469. doi:10.1177/0265691405054219. hdl:2440/124622. "In 1878, following a series of Christian uprisings against the Ottoman Empire, the Russo-Turkish War, and the Berlin Congress, Serbia gained complete independence, as well as new territories in the Toplica and Kosanica regions adjacent to Kosovo. These two regions had a sizable Albanian population which the Serbian government decided to deport."; p.470. "The ‘cleansing’ of Toplica and Kosanica would have long-term negative effects on Serbian-Albanian relations. The Albanians expelled from these regions moved over the new border to Kosovo, where the Ottoman authorities forced the Serb population out of the border region and settled the refugees there. Janjićije Popović, a Kosovo Serb community leader in the period prior to the Balkan Wars, noted that after the 1876–8 wars, the hatred of the Turks and Albanians towards the Serbs ‘tripled’. A number of Albanian refugees from Toplica region, radicalized by their experience, engaged in retaliatory violence against the Serbian minority in Kosovo... The 1878 cleansing was a turning point because it was the first gross and large-scale injustice committed by Serbian forces against the Albanians. From that point onward, both ethnic groups had recent experiences of massive victimization that could be used to justify ‘revenge’ attacks. Furthermore, Muslim Albanians had every reason to resist the incorporation into the Serbian state."

- ^ Pllana, Emin (1985). "Les raisons de la manière de l'exode des refugies albanais du territoire du sandjak de Nish a Kosove (1878–1878) [The reasons for the manner of the exodus of Albanian refugees from the territory of the Sanjak of Niš to Kosovo (1878–1878)]". Studia Albanica. 1: 189–190.

- ^ Rizaj, Skënder (1981). "Nënte Dokumente angleze mbi Lidhjen Shqiptare të Prizrenit (1878–1880) [Nine English documents about the League of Prizren (1878–1880)]". Gjurmine Albanologjike (Seria e Shkencave Historike). 10: 198.

- ^ Şimşir, Bilal N, (1968). Rumeli’den Türk göçleri. Emigrations turques des Balkans [Turkish emigrations from the Balkans]. Vol I. Belgeler-Documents. p. 737.

- ^ Bataković, Dušan (1992). The Kosovo Chronicles. Plato.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical Dictionary of Kosovo. Scarecrow Press. p. XXXII. ISBN 9780333666128.

- ^ Lampe 2000, p. 55"Before and after the army's withdrawal, the new Ottoman Sultan, Abdul Hamid II, unleashed Kosovar Albanian auxiliaries on the remaining Serbs."

- ^ a b c d e f g h Krakov 1990, p. 11

- ^ a b Institut za savremenu istoriju 2007, p. 86

- ^ a b c d e f Krakov 1990, p. 12

- ^ a b Popović 1900, p. 87.

- ^ Krakov 1990, pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Društvo sv. Save 1928, p. 58.

- ^ Društvo sv. Save 1930, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Krakov 1990, p. 13

- ^ a b c Krakov 1990, p. 14

- ^ Little 2007, p. 125"In time the Albanian nationalists became more overtly anti-Christian, eventually advocating something what today would be called "ethnic cleansing," an alarming movement that encouraged many Serbs to leave Kosovo."

Sources[]

- Krakov, Stanislav (1990) [1930]. Plamen četništva (in Serbian). Belgrade: Hipnos. (in Serbian)

- Institut za savremenu istoriju (2007). Gerila na Balkanu (in Serbian). Tokyo: Institute for Disarmament and Peace Studies. (in Serbian)

- Popovi��, Zarija R. (1900). Pred Kosovom: beleške iz doba 1874-1878 godine. Drž. štamp. Kralj. Srbije. pp. 86–87.

Панађуриште беше центар арнаутских напада. Дођоше пет Арнаута пред врата Јованове куће и стадоше лупати.

- Milan Budisavljević; Paja Adamov Marković; Dragutin J. Ilić (1899). Brankovo kolo za zabavu, pouku i književnost. Vol. 5.

Али догађај 26. јануара 1878. године остаће крвавим словима записан на лнетоии- ма историје града Приштине.

- Društvo sv. Save (1928). Brastvo. Vol. 22. Društvo sv. Save. p. 58.

Али је напад поглавито био управљен на Панађуриште, а у Панађуришту на кућу Јована Ђаковца. Јован је по зањимању пушкар. Његово српско одушев- љење било је појачано утицајем приштевачког учитеља Кова- чевића, коме је Јован често одлазио. И кад би Јован са својим шеснаестогодишњим сином ишао јутром у дућан, или се ве- чером враћао из дућана, били су вазда наоружани револверима и мартинкама. Турци би на овако наоружане кауре попреко гледали, ...

- Društvo sv. Save (1930). Brastvo. Vol. 24–26. Društvo sv. Save.

После неколико дана је у Приштини настала сеча Срба од Арнаута Малесораца којих је био пун град. Нарочито је био напад у махали Панађуришту на кућу непокорног Јована Ђаковца пушкара. Јован се јуначки борио, док му није кућа упаљена те му загрожена опасносг да се у диму угуши или да у пламену изгори. Заменивши своје главе десетороструко главама арнаутским, најзад су јуначки пали Јован, жена му и шурак.

- Lampe, John R. (28 March 2000). Yugoslavia as History: Twice There Was a Country. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77401-7.

- Little, David (2007). Peacemakers in Action: Profiles of Religion in Conflict Resolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-85358-3.

- Михаило Воjводић (1978). Србија 1878: документи. Српска књижевна задруга.

- Vladimir Stojančević (1998). Srpski narod u Staroj Srbiji u Velikoj istočnoj krizi 1876-1878. Službeni list SRJ.

- Bor. M. Karapandžić (1986). Srpsko Kosovo i Metohija: zločini Arnauta nad srpskim narodom. sn.n.

- Serbian–Turkish Wars (1876–1878)

- Massacres in the Ottoman Empire

- Serbian–Albanian conflict

- Kosovo Serbs

- Persecution of Serbs

- Kosovo Vilayet

- 1876 in the Ottoman Empire

- 1877 in the Ottoman Empire

- 1878 in the Ottoman Empire

- Ottoman Serbia

- 1876 in Serbia

- 1877 in Serbia

- 1878 in Serbia

- 19th century in Serbia

- Pogroms

- Massacres of Serbs

- Persecution of Christians in the Ottoman Empire