Automat

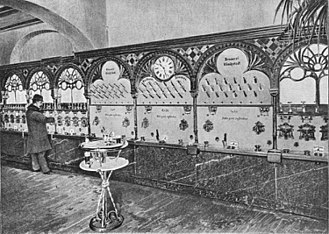

An automat is a fast food restaurant where simple foods and drinks are served by vending machines. The world's first automat was named Quisisana, which opened in Berlin, Germany in 1895.

By country[]

Germany[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (June 2017) |

The first automat in the world was the Quisisana automat, which opened in 1895 in Berlin, Germany.[3]

Japan[]

In Japan, in addition to regular vending machines which sell prepared food, many restaurants also use food ticket machines (Japanese: 食券機, romanized: shokkenki), where one purchases a meal ticket from a vending machine, then presents the ticket to a server, who then prepares and serves the meal. Conveyor belt sushi restaurants are also popular.

Netherlands[]

Automats (Dutch: automatiek) provide a variety of typical Dutch fried fast food, such as frikandellen and croquettes, but also hamburgers and sandwiches from vending machines that are back-loaded from a kitchen. FEBO is the best-known chain of Dutch automats. Some outlets are open 24 hours a day, and are popular with locals, and those leaving clubs and bars late at night. The Dutch concept has been successfully exported overseas.[clarification needed]

United States[]

Originally, the machines in U.S. automats took only nickels.[4] In the original format, a cashier sat in a change booth[citation needed] in the center of the restaurant, behind a wide marble counter with five to eight rounded depressions. The diner would insert the required number of coins in a machine and then lift a window, hinged at the top, and remove the meal, usually wrapped in waxed paper. The machines were replenished from the kitchen behind. All or most New York automats had a cafeteria-style steam table where patrons could slide a tray along rails and choose foods, which were ladled from tureens.

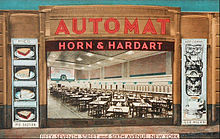

The first automat in the U.S. was opened June 12, 1902, at 818 Chestnut St.[2] in Philadelphia by Horn & Hardart; Horn & Hardart became the most prominent American automat chain.[5] Inspired by Max Sielaff's AUTOMAT Restaurants in Berlin, they became among the first 47 restaurants, and the first non-Europeans, to receive patented vending machines from Sielaff's Berlin factory.[2] The automat was brought to New York City[2] in 1912,[6] and gradually became part of popular culture in northern industrial cities.

The automats were popular with a wide variety of patrons, including Walter Winchell, Irving Berlin and other celebrities of the era. The New York automats were popular with unemployed songwriters and actors. Playwright Neil Simon called automats "the Maxim's of the disenfranchised" in a 1987 article.[7]

The format was threatened by the arrival of fast food, served over the counter and with more payment flexibility than traditional automats. By the 1970s, the automats' remaining appeal in their core urban markets was strictly nostalgic. Another contributing factor to their demise was the inflation of the 1970s, increasing food prices which made the use of coins increasingly inconvenient in a time before bill acceptors commonly appeared on vending equipment.[citation needed]

At one time, there were 40 Horn & Hardart automats in New York City alone. The last one closed in 1991. Horn and Hardart converted most of its New York City locations to Burger King. At the time, the quality of the food was described by some customers as on the decline.[7][8]

2000s US revivals[]

In an attempt to bring back automats in New York City, a company called Bamn! opened a new East Village Dutch-style automat store in 2006,[9] but it closed in 2009. [10] In 2015, another attempt was made, by a San Francisco company called Eatsa, which opened six automated restaurants in California, New York and the District of Columbia, but closed them all by 2019. The company rebranded itself as Brightloom, and continues to sell automation technology to restaurants (which includes software for ordering kiosks, mobile apps, digital signage, etc., to facilitate order pickup).

The COVID-19 Pandemic has inspired a new wave of automat revival attempts, to adapt to the deadly disease and the desire for contactless dining. Joe Scutellaro and Bob Baydale opened an Automat Kitchen in Jersey City's Newport Centre shopping mall in early 2021, which uses technology similar to what Brightloom offers, and specializes in fresh food. [11][12] Another is the Brooklyn Dumpling Shop, which as of 2021 is still planning to open in the East Village, not far from the Bamn! location.[13]

An automat in Manhattan, New York City in 1936.

A modern automat in Manhattan's East Village, circa 2007.[4]

Automat at 1165 Sixth Avenue, New York City, in the 1930s.

A Horn & Hardart postcard explaining how food was served in an automat (c. 1930s).

Rail transport[]

A form of the automat was used on some passenger trains. The Great Western Railway in the United Kingdom announced plans in December 1945 to introduce automat buffet cars.[14] Plans were delayed by impending nationalisation, and an automat was finally introduced on the Cambrian Coast Express, in 1962.[15]

In the United States, the Pennsylvania Railroad introduced an automat between Pennsylvania Station, New York City and Union Station, Washington, DC, in 1954.[16] Southern Pacific Railroad introduced automat buffet cars on the Coast Daylight and Sunset Limited in 1962. Amtrak converted four buffet cars to automats in 1985 for use on the Auto Train. The last one in use in the United States was on the short-lived Lake Country Limited in 2001.

In Switzerland, Bodensee–Toggenburg Bahn introduced automat buffet cars, in 1987.[17]

See also[]

- Automated restaurant

- Automated retail

- Cafeteria

- Conveyor belt sushi

- Full-line vending

References[]

- ^ Bernardo Friese, grandson of Max Sielaff

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Automat-Restaurants – AUTOMAT GmbH, 23 Spenerstrasse, Berlin, N.W. :: Trade Catalogs and Pamphlets - oclc

- ^ Smith, A.F.; Oliver, G. (2015). Savoring Gotham: A Food Lover's Companion to New York City. Oxford University Press, Incorporated. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-19-939702-0. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lui, Claire (2006). "Bamn! The Automat Is Back – Restaurant – Food & Drink". American Heritage Magazine. Archived from the original on 2007-10-20. Retrieved 2015-03-15.

- ^ "Horn & Hardart Automat, 968 6th Ave. between 35th & 36th Sts. (1986)", 36th Street, New York City Signs -- 14th to 42nd Street.

- ^ "Automats become a thing of the past in New York". Free Lance-Star. (Fredericksburg, Virginia). Associated Press. December 31, 1977. p. 12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Barron, James (April 11, 1991). "Last Automat Closes, Its Era Long Gone". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ "New York's Last Automat Closes". St. Petersburg Times. Associated Press. April 11, 1991. Retrieved 2009-07-16.

- ^ Matthews, Karen (August 28, 2006). "Updated Automat to open in New York City". boston.com. Associated Press. Retrieved 2006-08-28.

- ^ Amanda Kludt (March 9, 2009). "The Shutter: Felled Bamn! to Become Baoguette?". Eater NY.

- ^ Charlesworth, Michelle (January 27, 2021). "Blast from the past: Automat returns with a modern twist". ABC 7 Eyewitness News. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ Hamstra, Mark (February 3, 2021). "Automat Kitchen puts modern spin on classic no-contact format". Restaurant Hospitality. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ Warerkar, Tanay (January 21, 2021). "A First Look at Brooklyn Dumpling Shop's Automat". Eater New York. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- ^ "Automat Buffet Cars For British Railways". Reuters. 26 December 1945.

- ^ "Railway Gazette". The Railway Gazette. 119: 709. 1963.

- ^ "Automatic Buffet-Bar Car Introduced By Pennsy". Locomotive Engineers Journal. Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers. 88: 236. 1954.

- ^ Jane's World Railways. Jane's Yearbooks. 1988. p. 700. ISBN 0-7106-0871-3.

Further reading[]

- "The Last Automat," by James T. Farrell (New York, May 14, 1979)

- Automatenrestaurant Qusisana, Mariahilfer Straße 34 im 7, Vienna, Austria, 1972 from Pohanka, Reinhard; Sinalco-Epoche kenne ich

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Automats. |

- In Praise of the Automat – slideshow by Life magazine

- Sielaff Automaten Berlin – Max Sielaff, Automat inventor website

- Used and new Automats in the United States

- Doris Day at the Automat in That Touch of Mink (1962)

- Before Horn & Hardart: European automats

- Token from Automatencafe Quisisana, 57 Kärntner street, Vienna, Austria

- Automat Restaurants :: Trade Catalogs and Pamphlets - oclc

- Automat Restaurants – over 100 years ago – My Stockholm BLOG

- Fast-food restaurants

- Restaurants by type

- Vending

- Automation

- Retail formats