Axis war crimes in Italy

| Axis war crimes in Italy | |

|---|---|

| Part of Mediterranean theatre of World War II | |

| |

| Location | Italian Social Republic |

| Date | 8 September 1943 – 8 May 1945 |

| Target | Italian JewsItalian civilian populationItalian military internees |

| Deaths | Italian Jews 8,000Italian civilian population 14,000Italian military internees 40,000 |

Two of the three Axis powers of World War II—Nazi Germany and their Fascist Italian allies—committed war crimes in the Kingdom of Italy.

Research funded by the German government and published in 2016 found the number of victims of Nazi war crimes in Italy to be 22,000, double the previously estimated figure. Most victims were Italian civilians, sometimes in retaliation for partisan attacks, and Italian Jews.[1] This figure does not include Italian military internees: approximately 40,000 of them died in German captivity.[2]

The above estimate excludes the estimated 30,000 Italian partisans who were killed during the war.[clarification needed].[3]

The killing of Italian civilians by frontline units of the Wehrmacht and SS has sometimes been seen as stemming from a sense of betrayal the Germans felt due to the Italian surrender; and by a feeling of racial superiority. However, some historians have argued that the reasons for atrocities and the brutal behaviour were more complex, often resulting from the military crisis caused by the German retreats and the fear of ambushes.[3]

Only a few perpetrators were ever tried for these war crimes. Few of these served prison sentences because of Germany's refusal to prosecute and extradite war criminals to Italy.[1] The Italian government, in the early postwar decades, also made little effort to bring German war criminals to justice by demanding extradition: it feared that such demands would in turn encourage other countries to demand the extradition of Italian citizens accused of war crimes committed while Italy was allied with Nazi Germany.[4]

Background[]

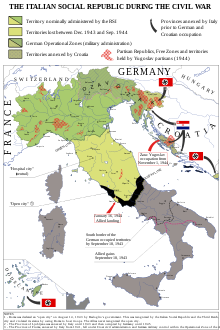

The Kingdom of Italy, until 8 September 1943, was an ally of Nazi Germany and part of the Axis powers. After the Armistice of Cassibile on 8 September and the surrender of Italy to the Allies, the fascists established the Italian Social Republic, the Repubblica Sociale Italiana or RSI, in the northern regions remaining under German control. The new republic, with Benito Mussolini as head of state, was a German puppet state: its government was under German control.[5]

Even before these events Germany had begun distrusting Italy as an ally and, by July 1943, had begun sending substantial numbers of troops to northern Italy while fighting against the Allies took place in Sicily and southern Italy, preparing for an occupation of northern and central Italy. By the time Italy surrendered, 200,000 German soldiers were deployed in northern Italy. The official purpose was to protect it from an Allied invasion, and to secure supply lines. In reality, the goals included disarming the Italian Army and occupying the part of the country, thereby securing Italian economic resources for Germany's benefit.[6]

War crimes committed by German soldiers pre-date the Italian surrender. For example, at Castiglione di Sicilia, 16 civilians were murdered by the 1st Fallschirm-Panzer Division Hermann Göring on 12 August 1943.[7]

Victims[]

The Holocaust in Italy[]

Italian Jews suffered far less persecution in Fascist Italy than the Jews in Nazi Germany did in the lead up to World War II. In the territories occupied by the Italian Army in France and Yugoslavia after the outbreak of World War II Jews even found protection from persecution.[8] The Italian racial laws of 1938 worsened their situation and the latter aided Nazi Germany after the Italian surrender on 8 September 1943 as it provided them with lists of Jews living in Italy.[9] Of the estimated 40,000 Jews living in Italy at the time, comprising Italian citizens and foreign refugees, 8,000 perished during the Holocaust.[5]

SS-Obergruppenführer Karl Wolff, the Highest SS and Police leader in Italy was tasked with overseeing the final solution, the genocide of the Jews. Wolff assembled a group of SS personnel under his command that had experience in the extermination of Jews in Eastern Europe. Odilo Globocnik, appointed as police leader for the coastal area, had been responsible for the murder of hundreds of thousands of Jews and Gypsies in Lublin, Poland, before his assignment to Italy.[10] Karl Brunner was appointed as SS and police leader in Bolzano, South Tyrol, in Monza for upper and western Italy and Karl-Heinz Bürger was placed in charge of anti-partisan operations.[11]

The security police and the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) were under the command of Wilhelm Harster, based in Verona, who had previously held the same position in the Netherlands.[12] Theodor Dannecker, previously active in the deportation of Greek Jews in the part of Greece occupied by Bulgaria, was made chief of the Judenreferat of the SD and was tasked with the deportation of the Italian Jews. Not seen as efficient enough, he was later replaced by Friedrich Boßhammer, who was, like Dannecker, closely associated with Adolf Eichmann. Dannecker committed suicide after being captured in December 1945 while Boßhammer assumed a false name after the war. He was discovered and sentenced to life in West Germany in 1972 but died before ever serving any time.[13][14]

The attitude of the Italian Fascists towards Italian Jews changed fundamentally in November 1943: the Fascist authorities declared them to be of "enemy nationality" during the Congress of Verona and begun to actively participate in the prosecution and arrest of Jews. However, the prosecution by Italian authorities did not extend to people descended from mixed marriages.[15] Initially, after the Italian surrender, the Italian police had only assisted in the round up of Jews when requested to do so by the German authorities. With the Manifest of Verona, in which Jews were declared to be foreigners and, in times of war, enemies, this changed. Police Order No. 5 on 30 November 1943, issued by the minister of the interior of the RSI Guido Buffarini Guidi, ordered the Italian police to arrest Jews and confiscate their property.[16][17]

Italian civilians[]

Approximately 14,000 Italian non-Jewish civilians, often women, children and elderly, have been documented to have died in over 5,300 individual instances of war crimes committed by Nazi Germany. The largest of those was the Marzabotto massacre, where in excess of 770 civilians were murdered. The Sant'Anna di Stazzema massacre saw 560 civilians killed while the Ardeatine massacre saw 335 randomly selected people executed, among them 75 Italian Jews.[9] In the Padule di Fucecchio massacre up to 184 civilians were executed.[18]

Italian military internees[]

With the Italian surrender on 8 September Germany disarmed a large part of the Italian Army and made them prisoners. Instead of awarding them prisoner of war status they were left with a choice of joining the armed forces of the Italian Social Republic or to become military internees. The majority chose the latter and approximately 600,000 of those were sent to Germany and to work as Nazi forced labour. Of those around 40,000 died through murder, hunger and cold in the harsh conditions they had to endure. In the winter of 1944–45 the Italian military internees were designated civilians by Nazi Germany to integrate them more effectively in the forced labour required for the armament industry. This step was declared illegal by the German government in 2001, thereby declaring them as prisoners of war and barring the survivors from compensation.[2]

Allied servicemen[]

Some Allied servicemen were executed after having been captured by German troops. The commander of the LXXV Army Corps, Anton Dostler, was sentenced to death and executed in 1945 for ordering the execution of fifteen American soldiers who had been captured during a commando raid behind German lines,[19] while SS officers Heinrich Andergassen and as well as Oberscharführer were convicted and executed for the murders of seven other Allied soldiers. Some of the accused used the Commando Order in their defence but this was rejected.[20][21][22]

Camps[]

German and Italian run transit camps for Jews, political prisoners and forced labour existed in Italy:[23]

- Bolzano camp, located in the Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol region, part of the Operational Zone of the Alpine Foothills at the time, operating as a German-controlled transit camp from summer 1944 to May 1945.[24][25]

- Borgo San Dalmazzo camp, located in the Piedmont region, operating as a German-controlled transit camp from September 1943 to November 1943 and, under Italian control, from December 1943 to February 1944.[26][27]

- Fossoli camp, located in the Emilia-Romagna region, operating as a prisoner of war camp under Italian control from May 1942 to September 1943, then as a transit camp, still under Italian control until March 1944 and, from then until November 1944 under German control.[28]

Apart from those three transit camps Germany also operated the Risiera di San Sabba camp, located in Trieste, then part of the Operational Zone of the Adriatic Littoral, which simultaneously functioned as an extermination and transit camp. It was the only extermination camp in Italy during World War II and operated from October 1943 to April 1945, with up to 5,000 people killed there.[29][30]

Apart from designated camps Jews and political prisoners were also held at common prisons, like the San Vittore Prison in Milan, which gained notoriety during the war through the inhumane treatment of inmates by the SS guards and the torture carried out there.[31]

Perpetrators[]

War crimes by Nazi Germany in Italy were committed by various branches of the German military and security forces. The Gestapo, SS and its Sicherheitsdienst were involved in the prosecution and murder of Italian Jews and the Ardeatine massacre,[9] while Waffen-SS and Wehrmacht units were responsible for the majority of war crimes committed against Italian civilians. The 1st SS Panzer Division was responsible for Boves massacre, shortly after the Italian surrender and, while neither instructed nor authorised to carry out arrests and executions of Jews, participated in both on its own accord immediately after the Italian surrender. The division also looted Jewish property and had to be explicitly stopped by SS corps commander Paul Hausser on the grounds that only the security police and the SD were authorised to carry out those measures.[32]

The 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division committed the Marzabotto and Sant'Anna di Stazzema massacres, the two worst atrocities in Italy as far as number of victims goes. The division was also involved in the Vinca massacre, where 162 Italian civilians were executed,[33] the San Terenzo Monti massacre, 159 victims,[34] and the , 149 victims.[35]

Wehrmacht units were also involved in massacres in Italy, with the murdering 57 civilians in the Guardistallo massacre and the 26th Panzer Division up to 184 civilians in the Padule di Fucecchio massacre.[18] Soldiers of the latter division are also alleged to have committed the murder of the family of Robert Einstein, a cousin of Nobel Prize Laureate Albert Einstein.[36][37] The 1st Fallschirm-Panzer Division Hermann Göring was involved in massacres, at (173 victims),[38] (130 victims),[39] (107 victims)[40] and (146 victims).[41]

The German 65th Infantry Division was reportedly responsible for two war crimes. In October 1943, two SAS men were captured after stealing a German vehicle, and executed on order of higher headquarters.[42] On 21 June 1944, a partisan attack on the headquarters of Artillery Regiment 165 (the 65th Division's organic artillery regiment) resulted in a soldier being wounded. The regimental commander ordered a reprisal killing of five Italian civilians.[43]

Apart from the Wehrmacht and Waffen-SS divisions, three of the four divisions of the National Republican Army of the Italian Socialist Republic, the 2nd Infantry division Littorio, the 3rd Marine divisionSan Marco and the 4th Alpine division Monterosa, have been identified as having taken part in war crimes.[44][45][46] The worst of those, at Col du Mont Fornet in the Valle d'Aosta on 26 January 1945, saw four members of the Monterosa division found guilty for the death of 33 forced labourers who perished in an avalanche while forced to carry military supplies to a mountain outpost despite severe weather conditions. Four Italian officers were charged and two sentenced to a ten-year jail term but pardoned in a 1947 general amnesty.[47]

Post war[]

With the 1947 Paris Peace Treaties Italy waived any compensation claims against other countries, including Germany (Article 77).[48] The 1961 Bilateral Compensation Agreement between West Germany and Italy resulted in a payment of DM 40 million. The latter was part of a set of agreements which West Germany concluded with twelve countries, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom, paying DM 876 million in what it considered voluntary compensation, without legal obligation.[49][50] In this agreement Italy declared "all outstanding claims on the part of the Italian Republic or Italian natural or legal persons against the Federal Republic of Germany or German natural or legal persons to be settled".[48]

Because of these agreements Germany denied any financial liability for compensation claims by Italian war crime victims and their family members.[51] It also eliminated Germany's legal obligation to extradite war criminals to Italy.[52] After repeated cases of Germany being ordered to pay compensation by Italian courts, Germany took the matter to the International Court of Justice, claiming immunity. In 2012 the ICJ ruled in Germany's favour.[53]

Prosecution[]

Only very few Nazi war criminals have ever served jail sentences in Italy for war crimes, among them Erich Priebke, Karl Hass, Michael Seifert,[52] Walter Reder and Herbert Kappler. Only a few German military personnel were placed on trial in Italy in the first five years after the war up to 1951, with twelve court cases and twenty five accused. After 1951 only a handful of trials were conducted until 1996, when the case against Erich Priebke started a new wave of court cases.[54] By then, in many cases, because decades had elapsed between the crimes and their prosecution, the accused either had died already, died during the court case or were deemed to old to be extradited or serve time in jail. An example of those is the San Cesario sul Panaro massacre, where twelve civilians were killed and where three of the four officers accused died before the trial commenced in 2004 and the fourth one died on the second day of the trial, leaving the massacre without legal repercussions for the perpetrators.[55]

Allied military courts tried high-ranking officers in Italy in the first post-war years. Generalfeldmarschall Albert Kesselring, German commander in the Mediterranean theatre, was tried in Venice for war crimes, found guilty, sentenced to death, but released in 1952. Eduard Crasemann, commander of the 26th Panzer Division, which was involved in the Padule di Fucecchio massacre, was found guilty of war crimes and sentenced to 10 years imprisonment. He spent the rest of his life in jail, dying in Werl, West Germany, on 28 April 1950. Max Simon, commander of the 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division, involved in the Marzabotto and Sant'Anna di Stazzema massacres, was sentenced to death by a British court but pardoned in 1954. Eberhard von Mackensen and Kurt Mälzer were both sentenced to death in Rome but this sentence was later commuted.[19]

Heinrich Andergassen, alongside two others, was sentenced by a US military tribunal and executed in 1946 in Pisa, Italy for his role in execution of OSS agent Roderick Stephen Hall and six other allied soldiers.[20]

From 1948 onward Italian military courts took over the prosecution of suspected German war criminals, sentencing 13 of them. Lieutenant-colonel Herbert Kappler, Major Walter Reder, Lieutenant-general Wilhelm Schmalz and Major were among the German officers put on trial, with Kappler and Reder receiving life sentences.[19]

Anton Dostler, commander of the LXXV Army Corps, was sentenced to death and executed in 1945 for ordering the execution of 15 US soldiers who had been captured during a commando raid behind German lines.[19]

Karl Friedrich Titho, SS-Untersturmführer and commander of the Fossoli di Carpi and Bolzano Transit Camps, was convicted after the war in the Netherlands for his role in executions there. He was deported to Germany in 1953 after the Netherlands had declined an extradition request by Italy in 1951. Despite an arrest warrant in Italy in 1954 Titho was never extradited and died in Germany in 2001, never having gone to trial for his role as camp commander in Italy.[56]

In 1994 a cabinet was discovered in Rome containing 695 files documenting war crimes committed during World War II in Italy, the Cabinet of shame (Italian: Armadio della vergogna).[57]

Theo Saevecke, head of the Gestapo and in Milan, was protected from prosecution through his high-ranking connections in post-war Germany. In 1999 he was sentenced in absentia in Turin to life imprisonment for his involvement in the execution of 15 hostages in Milan, on Piazzale Loreto, in August 1944 but never extradited to Italy.[58]

In 2011 military court in Italy tried four of the suspected perpetrators of the Padule di Fucecchio massacre and found three of them guilty while the fourth one died during the trial. Ernst Pistor (Captain), Fritz Jauss (Warrant officer), and Johan Robert Riss (Sergeant) were found guilty while Gerhard Deissmann died before the sentencing, aged 100. The three were unlikely to serve time in jail because Germany was not obliged to extradite them. None of the three showed any remorse for their action.[52][51]

In 2012 Italian foreign minister Giulio Terzi di Sant'Agata stated, in the presence of the late German Foreign Minister Guido Westerwelle, that Italy would continue to press Germany to extradite or trial locally war criminals sentenced in absentia in Italy.[59]

Few German soldiers accused or convicted of taking part in war crimes have shown remorse for their actions. , a member of the 16th SS Panzergrenadier Division Reichsführer-SS convicted of taking part in the Sant'Anna di Stazzema massacre, admitted that he killed 20 women during the massacre and that his actions haunted him throughout life.[60] Karl Friedrich Titho, commander of the Fossoli di Carpi and Bolzano Transit Camps, shortly before his death admitted that he was, as a member of the SS, guilty of crimes committed in his area of operation and that it had affected him all his life. He apologised to the victims and their family members.[61]

Research[]

Research into the German atrocities in Italy during the war, especially as part of the anti-partisan warfare, was long neglected, Italy being considered a minor theater in comparison to the much larger scale of atrocities committed in Eastern Europe. Consequently, major research by historians into the atrocities committed in Italy only really commenced in the 1990s.[3]

German military historian Gerhard Schreiber (1940–2017) specialised in the German-Italian relations during the Nazi era and published books on the German war crimes in Italy.[62]

Carlo Gentile of the University of Cologne published books and papers on the war in Italy, the war against the Italian partisans and the atrocities committed by Axis forces. He was also used as an historical expert in several trials against Germans accused of war crimes in Italy.[63]

In 2013 Italy and Germany agreed to conduct a study into the war crimes committed by Nazi Germany during World War II, funded by the German government. This study, completed in 2016, resulted in the Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy (Italian: Atlante delle Stragi Naziste e Fasciste in Italia), which was made available online. This new research established the number of victims to be in excess of 22,000, double the previous estimate. While this new research funded by the German government was applauded it was also seen as insufficient by one of the authors to compensate for the lack of prosecution of suspected war criminals and the lack of extradition of convicted ones.[1]

Commemoration[]

Memoriale della Shoah[]

The Memoriale della Shoah is a memorial in Milano Centrale railway station, dedicated to the Jewish people deported from there to the extermination camps and was opened in January 2013.[31]

Padule di Fucecchio massacre[]

In 2015, the Italian Foreign Minister, Paolo Gentiloni, together with his German counterpart Frank Walter Steinmeier, who would later serve as President of Germany, opened a Documentation Centre on the Padule di Fucecchio Massacre.[64]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Armellini, Arvise (5 April 2016). "New Study: Number of Casualties in Nazi Massacres in Italy Nearly Double as Previously Believed". Haaretz. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "8. September 1943: Die italienischen Militärinternierten". Zwangsarbeit 1939–1945 (in German). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Neitzel, Sönke. "Book Review by Sönke Neitzel in War in History: Wehrmacht und Waffen-SS im Partisanenkrieg: Italien 1943–1945". University of Cologne. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ Wiegrefe, Klaus (19 January 2012). "How Postwar Germany Let War Criminals Go Free". Der Spiegel. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The "Final Solution": Estimated Number of Jews Killed". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ Gentile, p. 2–3

- ^ "Castiglione di Sicilia 12.08.1943" (in Italian). Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Gentile, p. 10

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The destruction of the Jews of Italy". The Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ Gentile, p. 4

- ^ Gentile, p. 5

- ^ Gentile, p. 6

- ^ "Dannecker, Theodor (1913–1945)" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ "Boßhammer, Friedrich (1906–1972)" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Gentile, p. 15

- ^ Zimmerman, Joshua D. (2005). Jews in Italy Under Fascist and Nazi Rule, 1922–1945. ISBN 978-0521841016. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ Megargee, Geoffrey P.; White, Joseph R. (2018). The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos. ISBN 978-0253023865. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The responsible". L'Eccidio del Padule di Fucecchio. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Military Courts". Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Andergassen, Heinrich (1908–1946)" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ "Schiffer, August (1901–1946)" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ Steinacher, Gerald (1999). ""In der Bozner Zelle erhängt…": Roderick Hall – Einziges Ein-Mann-Unternehmen des amerikanischen Kriegsgeheimdienstes in Südtirol" ["Hung in a cell in Bolzano...": Roderick Hall – The only one-man operation of the OSS in South Tyrol] (in German). University of Nebraska. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ Der Ort des Terrors: Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager Bd. 9: Arbeitserziehungslager, Durchgangslager, Ghettos, Polizeihaftlager, Sonderlager, Zigeunerlager,Zwangsarbeitslager (in German). Wolfgang Benz, Barbara Distel. 2009. ISBN 978-3406572388. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "BOLZANO". ANED – National Association of Italian political deportees from Nazi concentration camps. Archived from the original on 10 September 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "Bozen-Gries" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "BORGO SAN DALMAZZO". ANED – National Association of Italian political deportees from Nazi concentration camps. Archived from the original on 28 August 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "BORGO SAN DALMAZZO" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "FOSSOLI". ANED – National Association of Italian political deportees from Nazi concentration camps. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "SAN SABBA RICE MILL". ANED – National Association of Italian political deportees from Nazi concentration camps. Archived from the original on 10 September 2018. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "Risiera San Sabba" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Mailand" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ Gentile, p. 11 & 12

- ^ "VINCA FIVIZZANO 24–27.08.1944". Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ "SAN TERENZO MONTI FIVIZZANO 17-19.08.1944". Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ "SAN LEONARDO AL FRIGIDO MASSA 16.09.1944". Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ Kellerhoff, Sven Felix (21 February 2011). "Die ewige Suche nach dem Mörder der Einsteins" [The eternal search for the Einstein murderers]. Die Welt (in German). Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ Dosch, Stefan (23 August 2017). "Einsteins Nichten: Die tragische Geschichte von zwei Schwestern" [Einstein's nieces; The tragic story of two sisters]. Augsburger Allgemeine (in German). Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ "CAVRIGLIA 04.07.1944". Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ "MONCHIO SUSANO E COSTRIGNANO PALAGANO 18.03.1944". Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ "VALLUCCIOLE PRATOVECCHIO STIA 13.04.1944". Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ "CIVITELLA IN VAL DI CHIANA 29.06.1944". Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy (in Italian). Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ The Secret War in Italy: Special Forces, Partisans and Covert Operations 1943–45 by William Fowler, pp. 34–35

- ^ lexicon der wehrmacht

- ^ "2. Divisione granatieri "Littorio"" (in Italian). Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ "3. Divisione fanteria di marina "San Marco"/Presidio di Millesimo" (in Italian). Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ "4. Divisione Alpina "Monterosa"" (in Italian). Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ "COL DU MONT FORNET, VALGRISENCHE, 26.01.1945" (in Italian). Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jurisdictional Immunities of the State (Germany v. Italy), Judgment, ¶22-26 (Feb 3, 2012) Archived 13 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Bilateral Agreements and the Cold War (1956–1974)". German Federal Archives. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ "Claims Agreements with other Countries". Institute for Jewish Policy Research. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Squires, Nick (26 May 2011). "Three former Nazi soldiers found guilty of Tuscan massacre". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Three ex-Nazis get life for WWII massacre". Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata. 26 May 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "Jurisdictional Immunities of the State (Germany v. Italy: Greece intervening)". International Court of Justice. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Cornelißen, Christoph; Pezzino, Paolo (2017). Historikerkommissionen und Historische Konfliktbewältigung (in German). ISBN 978-3110541144. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ "San Cesario sul Panaro". Atlas of Nazi and Fascist Massacres in Italy (in Italian). Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ "Titho, Karl (1911–2001)" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ "Italy Publishes Thousands of Classified Files Related to Nazi Crimes". Haaretz. 16 February 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2018.

- ^ "Saevecke, Theo (1911–2000)" (in German). Gedenkorte Europa 1939–1945. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

- ^ "Italy to Press Germany on Conviction of ex-Nazis". Haaretz. 21 December 2012. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ "'Haunted' SS veteran stands trial for massacre of the innocents in village". The Daily Telegraph. 1 July 2004. Retrieved 18 September 2018.

- ^ Schwarzer, Marianne (17 February 2016). "Dem "Henker von Fossoli" blieb ein Prozess auf deutschem Boden erspart" [The „Executor of Fossoli“ is spared from a trial on German soil]. (in German). Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ Dernbach, Andrea (25 October 2013). "Erinnern statt entschädigen" [Remember instead of compensate]. Der Tagesspiegel. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ "Carlo Gebile". University of Cologne. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "The Italian and German foreign ministers open the Documentation Centre on the Padule di Fucecchio Massacre". Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation. 11 October 2015. Retrieved 12 August 2018.

Bibliography[]

- Carlo Gentile. The Police Transit Camps in Fossoli and Bolzano – Historical report in connection with the trial of Manfred Seifert. Cologne.

Further reading[]

In English[]

- Stephan D Yada-MC Neal (2018). Places of shame – German war crimes in Italy 1943–1945. Norderstedt: Books on demand. ISBN 978-3-7460-9795-4.

In German[]

- Gerhard Schreiber (1990). Die italienischen Militärinternierten im deutschen Machtbereich 1943 bis 1945 [The Italian military internees in the German zone of control 1943 to 1945] (in German). Munich: Oldenbourg. ISBN 3-486-55391-7.

- Gerhard Schreiber (1996). Deutsche Kriegsverbrechen in Italien. Täter, Opfer, Strafverfolgung [War crimes in Italy. Perpetrators, Victims, Prosecution] (in German). Munich: Beck. ISBN 3-406-39268-7.

External links[]

- Nazi war crimes in Italy

- The Holocaust in Italy

- Kingdom of Italy (1861–1946)

- Italian Social Republic

- Axis powers