Ayn Rand

Ayn Rand | |

|---|---|

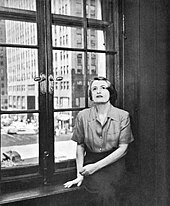

Rand in 1943 | |

| Native name | Алиса Зиновьевна Розенбаум |

| Born | Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum February 2, 1905 St. Petersburg, Russian Empire |

| Died | March 6, 1982 (aged 77) New York City, New York, U.S.A. |

| Resting place | Kensico Cemetery, Valhalla, New York, U.S.A. |

| Pen name | Ayn Rand |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Language | English |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | Petrograd State University (diploma in history, 1924) |

| Period | 1934–1982 |

| Subject | Philosophy |

| Notable works |

|

| Notable awards | Prometheus Award – Hall of Fame 1983 Atlas Shrugged 1987 Anthem |

| Spouse | |

| Signature |  |

Alice O'Connor (born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum;[a] February 2 [O.S. January 20], 1905 – March 6, 1982), better known by her pen name Ayn Rand (/aɪn/),[2] was a Russian-American writer and philosopher.[3][4] She is known for her fiction and for developing a philosophical system she named Objectivism. Born and educated in Russia, she moved to the United States in 1926. She wrote a play that opened on Broadway in 1935. After two early novels that were initially unsuccessful, she achieved fame with her 1943 novel, The Fountainhead. In 1957, Rand published her best-known work, the novel Atlas Shrugged. Afterward, until her death in 1982, she turned to non-fiction to promote her philosophy, publishing her own periodicals and releasing several collections of essays.

Rand advocated reason as the only means of acquiring knowledge; she rejected faith and religion. She supported rational and ethical egoism and rejected altruism. In politics, she condemned the initiation of force as immoral[5][6] and opposed collectivism, statism, and anarchism. Instead, she supported laissez-faire capitalism, which she defined as the system based on recognizing individual rights, including private property rights.[7] Although Rand opposed libertarianism, which she viewed as anarchism, she is often associated with the modern libertarian movement in the United States.[8] In art, Rand promoted romantic realism. She was sharply critical of most philosophers and philosophical traditions known to her, except for Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, and classical liberals.[9][10]

Rand's fiction received mixed reviews from literary critics.[11] Although academic interest in her ideas has grown since her death,[12][13] academic philosophers have generally ignored or rejected her philosophy because of her polemical approach and lack of methodological rigor.[4] Her writings have politically influenced some libertarians and conservatives.[14][15] The Objectivist movement attempts to spread her ideas, both to the public and in academic settings.[16]

Life[]

Early life[]

Rand was born Alisa Zinovyevna Rosenbaum on February 2, 1905, to a Russian-Jewish bourgeois family living in Saint Petersburg.[17] She was the eldest of three daughters of Zinovy Zakharovich Rosenbaum, a pharmacist, and Anna Borisovna (née Kaplan).[18] Rand later said she found school unchallenging and began writing screenplays at age eight and novels at age ten.[19] At the prestigious , her closest friend was Vladimir Nabokov's younger sister, Olga; the pair shared an intense interest in politics.[20][21]

She was twelve at the time of the February Revolution of 1917, during which Rand favored Alexander Kerensky over Tsar Nicholas II. The subsequent October Revolution and the rule of the Bolsheviks under Vladimir Lenin disrupted the life the family had enjoyed previously. Her father's business was confiscated, and the family fled to the Crimean Peninsula, which was initially under the control of the White Army during the Russian Civil War. While in high school there, Rand concluded she was an atheist and valued reason above any other virtue. After graduating in June 1921, she returned with her family to Petrograd (as Saint Petersburg was then named), where they faced desperate conditions, occasionally nearly starving.[22][23]

Following the Russian Revolution, universities were opened to women, allowing her to be in the first group of women to enroll at Petrograd State University.[24] At 16, she began her studies in the department of social pedagogy, majoring in history.[25] At the university, she was introduced to the writings of Aristotle and Plato;[26] Rand came to see their differing views on reality and knowledge as the primary conflict within philosophy.[27] She also studied the philosophical works of Friedrich Nietzsche.[28]

Along with many other bourgeois students, she was purged from the university shortly before graduating. After complaints from a group of visiting foreign scientists, many of the purged students were allowed to complete their work and graduate,[29][30] which she did in October 1924.[31] She then studied for a year at the State Technicum for Screen Arts in Leningrad. For an assignment, Rand wrote an essay about the Polish actress Pola Negri, which became her first published work.[32]

By this time, she had decided her professional surname for writing would be Rand,[33] possibly because it is graphically similar to a vowelless excerpt Рзнб of her birth surname Розенбаум in Cyrillic.[34][35] She adopted the first name Ayn.[b]

Arrival in the United States[]

In late 1925, Rand was granted a visa to visit relatives in Chicago.[39] She departed on January 17, 1926.[40] Arriving in New York City on February 19, 1926, Rand was so impressed with the Manhattan skyline that she cried what she later called "tears of splendor".[41] Intent on staying in the United States to become a screenwriter, she lived for a few months with her relatives. One of them owned a movie theater and allowed her to watch dozens of films free of charge. She then left for Hollywood, California.[42]

In Hollywood, a chance meeting with famed director Cecil B. DeMille led to work as an extra in his film The King of Kings and a subsequent job as a junior screenwriter.[43] While working on The King of Kings, she met an aspiring young actor, Frank O'Connor; the two married on April 15, 1929. She became a permanent American resident in July 1929 and an American citizen on March 3, 1931.[44][45][c] She made several attempts to bring her parents and sisters to the United States, but they were unable to obtain permission to emigrate.[48][49]

During these early years of her career, Rand wrote a number of screenplays, plays, and short stories that were not produced or published during her lifetime; some were published later in The Early Ayn Rand.[50]

Early fiction[]

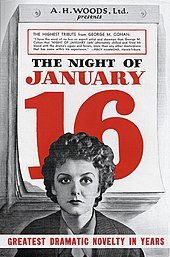

Although it was never produced, Rand's first literary success came with the sale of her screenplay Red Pawn to Universal Studios in 1932. [51] Her courtroom drama Night of January 16th, first produced by E. E. Clive in Hollywood in 1934, reopened successfully on Broadway in 1935. Each night, a jury was selected from members of the audience; based on its vote, one of two different endings would be performed.[52][d]

Her first published novel, the semi-autobiographical We the Living, was published in 1936. Set in Soviet Russia, it focused on the struggle between the individual and the state. Initial sales were slow, and the American publisher let it go out of print,[55] although European editions continued to sell.[56] She adapted the story as a stage play, but producer George Abbott's Broadway production was a failure and closed in less than a week.[57][e] After the success of her later novels, Rand was able to release a revised version in 1959 that has since sold over three million copies.[59] In a foreword to the 1959 edition, Rand wrote that We the Living "is as near to an autobiography as I will ever write. ... The plot is invented, the background is not ...".[60]

Rand wrote her novella Anthem during a break from writing her next major novel, The Fountainhead. It presents a vision of a dystopian future world in which totalitarian collectivism has triumphed to such an extent that even the word I has been forgotten and replaced with we.[61][62] Published in England in 1938, Rand could not find an American publisher initially. As with We the Living, Rand's later success allowed her to get a revised version published in 1946, which has sold over 3.5 million copies.[63]

The Fountainhead and political activism[]

During the 1940s, Rand became politically active. She and her husband worked as full-time volunteers for Republican Wendell Willkie's 1940 presidential campaign. This led to Rand's first public speaking experiences; she enjoyed fielding sometimes hostile questions from New York City audiences who had seen pro-Willkie newsreels.[64] Her work brought her into contact with other intellectuals sympathetic to free-market capitalism. She became friends with journalist Henry Hazlitt, who introduced her to the Austrian School economist Ludwig von Mises. Despite her philosophical differences with them, Rand strongly endorsed the writings of both men throughout her career, and both of them expressed admiration for her. Mises once referred to her as "the most courageous man in America", a compliment that particularly pleased her because he said "man" instead of "woman".[65][66] Rand became friends with libertarian writer Isabel Paterson. Rand questioned her about American history and politics long into the night during their many meetings, and gave Paterson ideas for her only non-fiction book, The God of the Machine.[67]

Rand's first major success as a writer came in 1943 with The Fountainhead, a romantic and philosophical novel that she wrote over seven years.[68] The novel centers on an uncompromising young architect named Howard Roark and his struggle against what Rand described as "second-handers"—those who attempt to live through others, placing others above themselves. Twelve publishers rejected it before the Bobbs-Merrill Company finally accepted it at the insistence of editor Archibald Ogden, who threatened to quit if his employer did not publish it.[69] While completing the novel, Rand was prescribed the amphetamine Benzedrine to fight fatigue.[70] The drug helped her to work long hours to meet her deadline for delivering the novel, but afterwards she was so exhausted that her doctor ordered two weeks' rest.[71] Her use of the drug for approximately three decades may have contributed to what some of her later associates described as volatile mood swings.[72][73]

The Fountainhead became a worldwide success, bringing Rand fame and financial security.[74] In 1943, she sold the film rights to Warner Bros. and returned to Hollywood to write the screenplay. Producer Hal B. Wallis hired her afterwards as a screenwriter and script-doctor. Her work for him included the screenplays for the Oscar-nominated Love Letters and You Came Along.[75] Rand worked on other projects, including a never-completed nonfiction treatment of her philosophy to be called The Moral Basis of Individualism.[76][77][f]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Rand extended her involvement with free-market and anti-communist activism while working in Hollywood. She became involved with the anti-Communist Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals and wrote articles on the group's behalf. She also joined the anti-Communist American Writers Association.[78] A visit by Paterson to meet with Rand's California associates led to a falling out between the two when Paterson made comments to valued political allies which Rand considered rude.[79][80] In 1947, during the Second Red Scare, Rand testified as a "friendly witness" before the United States House Un-American Activities Committee that the 1944 film Song of Russia grossly misrepresented conditions in the Soviet Union, portraying life there as much better and happier than it was.[81] She also wanted to criticize the lauded 1946 film The Best Years of Our Lives for what she interpreted as its negative presentation of the business world, but was not allowed to do so.[82] When asked after the hearings about her feelings on the investigations' effectiveness, Rand described the process as "futile".[83]

After several delays, the film version of The Fountainhead was released in 1949. Although it used Rand's screenplay with minimal alterations, she "disliked the movie from beginning to end" and complained about its editing, the acting and other elements.[84]

Atlas Shrugged and Objectivism[]

Following the publication of The Fountainhead, Rand received numerous letters from readers, some of whom the book had influenced profoundly.[85] In 1951, Rand moved from Los Angeles to New York City, where she gathered a group of these admirers around her. This group (jokingly designated "The Collective") included a future chair of the Federal Reserve Alan Greenspan, a young psychology student named Nathan Blumenthal (later Nathaniel Branden) and his wife Barbara, and Barbara's cousin Leonard Peikoff. Initially, the group was an informal gathering of friends who met with Rand at her apartment on weekends to discuss philosophy. Later, Rand began allowing them to read the drafts of her new novel, Atlas Shrugged, as she wrote the manuscript.[86] In 1954, her close relationship with Nathaniel Branden turned into a romantic affair, with the knowledge of their spouses.[87]

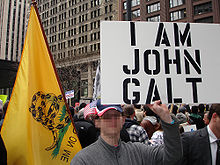

Published in 1957, Atlas Shrugged was considered Rand's magnum opus.[88][89] She described the novel's theme as "the role of the mind in man's existence—and, as a corollary, the demonstration of a new moral philosophy: the morality of rational self-interest".[90] It advocates the core tenets of Rand's philosophy of Objectivism and expresses her concept of human achievement. The plot involves a dystopian United States in which the most creative industrialists, scientists, and artists respond to a welfare state government by going on strike and retreating to a hidden valley where they build an independent free economy. The novel's hero and leader of the strike, John Galt, describes it as "stopping the motor of the world" by withdrawing the minds of the individuals contributing most to the nation's wealth and achievements. With this fictional strike, Rand intended to illustrate that without the efforts of the rational and productive, the economy would collapse and society would fall apart. The novel includes elements of mystery, romance, and science fiction,[91][92] and contains an extended exposition of Objectivism in a lengthy monologue delivered by Galt.[93]

Despite many negative reviews, Atlas Shrugged became an international bestseller,[94] however, the reaction of intellectuals to the novel discouraged and depressed Rand.[72][95] Atlas Shrugged was her last completed work of fiction marking the end of her career as a novelist and the beginning of her role as a popular philosopher.[96]

In 1958, Nathaniel Branden established the Nathaniel Branden Lectures, later incorporated as the Nathaniel Branden Institute (NBI), to promote Rand's philosophy. Collective members gave lectures for the NBI and wrote articles for Objectivist periodicals that Rand edited. She later published some of these articles in book form. Rand was unimpressed by many of the NBI students[97] and held them to strict standards, sometimes reacting coldly or angrily to those who disagreed with her.[98][99][100] Critics, including some former NBI students and Branden himself, later described the culture of the NBI as one of intellectual conformity and excessive reverence for Rand. Some described the NBI or the Objectivist movement as a cult or religion.[101][102] Rand expressed opinions on a wide range of topics, from literature and music to sexuality and facial hair. Some of her followers mimicked her preferences, wearing clothes to match characters from her novels and buying furniture like hers.[103] However, some former NBI students believed the extent of these behaviors was exaggerated, and the problem was concentrated among Rand's closest followers in New York.[100][104]

Later years[]

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Rand developed and promoted her Objectivist philosophy through her nonfiction works and by giving talks to students at institutions such as Yale, Princeton, Columbia,[105] Harvard, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[106] She began delivering annual lectures at the Ford Hall Forum, responding to questions from the audience.[107] During these appearances, she often took controversial stances on the political and social issues of the day. These included: supporting abortion rights,[108] opposing the Vietnam War and the military draft (but condemning many draft dodgers as "bums"),[109][110] supporting Israel in the Yom Kippur War of 1973 against a coalition of Arab nations as "civilized men fighting savages",[111][112] saying European colonists had the right to invade and take land inhabited by American Indians,[112][113] and calling homosexuality "immoral" and "disgusting", while also advocating the repeal of all laws concerning it.[114] She endorsed several Republican candidates for president of the United States, most strongly Barry Goldwater in 1964, whose candidacy she promoted in several articles for The Objectivist Newsletter.[115][116]

In 1964, Nathaniel Branden began an affair with the young actress Patrecia Scott, whom he later married. Nathaniel and Barbara Branden kept the affair hidden from Rand. When she learned of it in 1968, though her romantic relationship with Branden had already ended,[117] Rand ended her relationship with both Brandens, and the NBI was closed.[118] She published an article in The Objectivist repudiating Nathaniel Branden for dishonesty and other "irrational behavior in his private life".[119] In subsequent years, Rand and several more of her closest associates parted company.[120]

Rand underwent surgery for lung cancer in 1974 after decades of heavy smoking.[121] In 1976, she retired from writing her newsletter and, after her initial objections, allowed a social worker employed by her attorney to enroll her in Social Security and Medicare.[122][123] During the late 1970s, her activities within the Objectivist movement declined, especially after the death of her husband on November 9, 1979.[124] One of her final projects was work on a never-completed television adaptation of Atlas Shrugged.[125]

On March 6, 1982, Rand died of heart failure at her home in New York City.[126] She was interred in the Kensico Cemetery, Valhalla, New York.[127] At her funeral, a 6-foot (1.8 m) floral arrangement in the shape of a dollar sign was placed near her casket.[128] In her will, Rand named Leonard Peikoff as her beneficiary.[129]

Literary method and influences[]

Rand described her approach to literature as "romantic realism".[130] She wanted her fiction to present the world "as it could be and should be", rather than as it was.[131] This approach led her to create highly stylized situations and characters. Her fiction typically has protagonists who are heroic individualists, depicted as fit and attractive.[132] Her stories' villains support duty and collectivist moral ideals. Rand often describes them as unattractive and they sometimes have names that suggest negative traits, like Wesley Mouch in Atlas Shrugged.[133]

Rand considered plot a critical element of literature,[134] and her stories typically have what biographer Anne Heller described as "tight, elaborate, fast-paced plotting".[135] Romantic triangles are a common plot element in Rand's fiction; in most of her novels and plays, the main female character is romantically involved with at least two different men.[136][137]

Influences[]

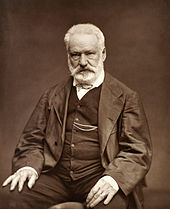

In school Rand read works by Fyodor Dostoevsky, Victor Hugo, Edmond Rostand, and Friedrich Schiller, who became her favorites.[138] She considered them to be among the "top rank" of Romantic writers because of their focus on moral themes and their skill at constructing plots.[139] Hugo, in particular, was an important influence on her writing, especially her approach to plotting. In the introduction she wrote for an English-language edition of his novel Ninety-Three, Rand called him "the greatest novelist in world literature". [140]

Although Rand disliked most Russian literature, her depictions of her heroes show the influence of the Russian Symbolists[141] and other nineteenth-century Russian writing, most notably the 1863 novel What Is to Be Done? by Nikolay Chernyshevsky.[142][143] Rand's experience of the Russian Revolution and early Communist Russia influenced the portrayal of her villains. This is most apparent in We the Living, set in Russia. The ideas and rhetoric of Ellsworth Toohey in The Fountainhead[144] and the destruction of the economy by the looters in Atlas Shrugged also reflect it.[145][146]

Rand's descriptive style echoes her early career writing scenarios and scripts for movies; her novels have many narrative descriptions that resemble early Hollywood movie scenarios. They often follow common film editing conventions, such as having a broad establishing shot description of a scene followed by close-up details, and her descriptions of women characters often take a "male gaze" perspective.[147]

Philosophy[]

| Objectivist movement |

|---|

|

|

Rand called her philosophy "Objectivism", describing its essence as "the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute".[148] She considered Objectivism a systematic philosophy and laid out positions on metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, political philosophy, and aesthetics.[149]

In metaphysics, Rand supported philosophical realism and opposed anything she regarded as mysticism or supernaturalism, including all forms of religion.[150] Rand believed in free will as a form of agent causation and rejected determinism.[151]

In epistemology, she considered all knowledge to be based on sense perception, the validity of which Rand considered axiomatic,[152][153] and reason, which she described as "the faculty that identifies and integrates the material provided by man's senses".[154] Rand rejected all claims of non-perceptual or a priori knowledge, including "'instinct,' 'intuition,' 'revelation,' or any form of 'just knowing'".[155] In her Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, Rand presented a theory of concept formation and rejected the analytic–synthetic dichotomy.[156][157]

In ethics, Rand argued for rational and ethical egoism (rational self-interest), as the guiding moral principle. She said the individual should "exist for his own sake, neither sacrificing himself to others nor sacrificing others to himself".[158] Rand referred to egoism as "the virtue of selfishness" in her book of that title.[3] In it, she presented her solution to the is-ought problem by describing a meta-ethical theory that based morality in the needs of "man's survival qua man".[4][159] She condemned ethical altruism as incompatible with the requirements of human life and happiness,[4] and held the initiation of force was evil and irrational, writing in Atlas Shrugged that, "Force and mind are opposites."[160][161]

Rand's political philosophy emphasized individual rights—including property rights. She considered laissez-faire capitalism the only moral social system because in her view it was the only system based on protecting those rights.[7] Rand opposed statism, which she understood included theocracy, absolute monarchy, Nazism, fascism, communism, democratic socialism, and dictatorship.[162] She believed a constitutionally limited government should protect natural rights.[163] Although her political views are often classified as conservative or libertarian, Rand preferred the term "radical for capitalism". She worked with conservatives on political projects, but disagreed with them over issues such as religion and ethics.[164][165] Rand denounced libertarianism, which she associated with anarchism.[8][166] She rejected anarchism as a naïve theory based in subjectivism that could only lead to collectivism in practice.[167]

In aesthetics, Rand defined art as a "selective re-creation of reality according to an artist's metaphysical value-judgments".[168] According to her, art allows philosophical concepts to be presented in a concrete form that can be grasped easily, thereby fulfilling a need of human consciousness.[169] As a writer, the art form Rand focused on most closely was literature. She considered romanticism to be the approach that most accurately reflected the existence of human free will.[170]

Rand said her most important contributions to philosophy were her "theory of concepts, ethics, and discovery in politics that evil—the violation of rights—consists of the initiation of force".[171] She believed epistemology was a foundational branch of philosophy and considered the advocacy of reason to be the single most significant aspect of her philosophy,[172] stating: "I am not primarily an advocate of capitalism, but of egoism; and I am not primarily an advocate of egoism, but of reason. If one recognizes the supremacy of reason and applies it consistently, all the rest follows."[173]

Criticisms[]

Rand's ethics and politics are the most criticized areas of her philosophy.[174] Numerous authors, including Robert Nozick and William F. O'Neill, in some of the earliest academic critiques of her ideas,[175] said she failed in her attempt to solve the is–ought problem.[176] Critics have called her definitions of egoism and altruism biased and inconsistent with normal usage.[177] Critics from religious traditions oppose her rejection of altruism in addition to atheism.[178] Essays criticizing Rand's egoistic views are included in a number of anthologies for teaching introductory ethics, often including no essays presenting or defending them.[179]

Multiple critics, including Nozick, have said her attempt to justify individual rights based on egoism fails.[180] Others, like Michael Huemer, have gone further, saying that her support of egoism and her support of individual rights are inconsistent positions.[181] Some critics, like Roy Childs, have said that her opposition to the initiation of force should lead to support of anarchism, rather than limited government.[182][183]

Commentators, including Hazel Barnes, Albert Ellis, and Nathaniel Branden, have criticized Rand's focus on the importance of reason. Branden said this emphasis led her to denigrate emotions and create unrealistic expectations of how consistently rational human beings should be.[184]

Relationship to other philosophers[]

Except for Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas and classical liberals, Rand was sharply critical of most philosophers and philosophical traditions known to her.[9][10] Acknowledging Aristotle as her greatest influence,[94] Rand remarked that in the history of philosophy she could only recommend "three A's"—Aristotle, Aquinas, and Ayn Rand.[185] In a 1959 interview with Mike Wallace, when asked where her philosophy came from, she responded: "Out of my own mind, with the sole acknowledgement of a debt to Aristotle, the only philosopher who ever influenced me. I devised the rest of my philosophy myself."[186]

In an article for the Claremont Review of Books, political scientist Charles Murray criticized her claim that her only "philosophical debt" was to Aristotle. He asserted her ideas were derivative of previous thinkers such as John Locke and Friedrich Nietzsche.[187] Rand found early inspiration from Nietzsche,[188][189][190] and scholars have found indications of this in Rand's private journals. In 1928, she alluded to his idea of the "superman" in notes for an unwritten novel whose protagonist was inspired by the murderer William Edward Hickman.[191][192][193] There are other indications of Nietzsche's influence in passages from the first edition of We the Living (which Rand later revised),[194][195] and in her overall writing style.[4][196] By the time she wrote The Fountainhead, Rand had turned against Nietzsche's ideas,[188][197] and the extent of his influence on her even during her early years is disputed.[198][199][200]

Rand considered her philosophical opposite to be Immanuel Kant, whom she referred to as "the most evil man in mankind's history";[201] she believed his epistemology undermined reason and his ethics opposed self-interest.[202] Philosophers George Walsh[203] and Fred Seddon[204] have argued she misinterpreted Kant and exaggerated their differences.

Reception and legacy[]

Critical reception[]

The first reviews Rand received were for Night of January 16th. Reviews of the Broadway production were largely positive, but Rand considered even positive reviews to be embarrassing because of significant changes made to her script by the producer.[205] Although Rand believed that her novel We the Living was not widely reviewed, over 200 publications published approximately 125 different reviews. Overall, they were more positive than those she received for her later work.[206] Her 1938 novella Anthem received little review attention, both for its first publication in England and for subsequent re-issues.[207]

Rand's first bestseller, The Fountainhead, received far fewer reviews than We the Living, and reviewers' opinions were mixed.[208] Lorine Pruette's positive review in The New York Times was one that Rand greatly appreciated.[209] Pruette called her "a writer of great power" who wrote "brilliantly, beautifully and bitterly", and said "you will not be able to read this masterful book without thinking through some of the basic concepts of our time".[210] There were other positive reviews, but Rand dismissed most of them for either misunderstanding her message or for being in unimportant publications.[208] Some negative reviews focused on the novel's length;[11] one called it "a whale of a book" and another said "anyone who is taken in by it deserves a stern lecture on paper-rationing". Other negative reviews called the characters unsympathetic and Rand's style "offensively pedestrian".[208]

Atlas Shrugged was widely reviewed, and many of the reviews were strongly negative.[11][211] In National Review, conservative author Whittaker Chambers called the book "sophomoric" and "remarkably silly".[212] He described the book's tone as "shrillness without reprieve". He accused Rand of supporting a godless system (which he related to that of the Soviets), claiming, "From almost any page of Atlas Shrugged, a voice can be heard, from painful necessity, commanding: 'To a gas chamber—go!'".[213] Atlas Shrugged received positive reviews from a few publications, including praise from the noted book reviewer John Chamberlain.[211] Rand scholar Mimi Reisel Gladstein later wrote that "reviewers seemed to vie with each other in a contest to devise the cleverest put-downs", saying it was "execrable claptrap", "written out of hate", and showed "remorseless hectoring and prolixity".[11]

Rand's nonfiction received far fewer reviews than her novels. The tenor of the criticism for her first nonfiction book, For the New Intellectual, was similar to that for Atlas Shrugged.[214][215] Philosopher Sidney Hook likened her certainty to "the way philosophy is written in the Soviet Union",[216] and author Gore Vidal called her viewpoint "nearly perfect in its immorality".[217] Her subsequent books got progressively less review attention.[214]

On the 100th anniversary of Rand's birth in 2005, writing for The New York Times, Edward Rothstein referred to her written fiction as quaint utopian "retro fantasy" and programmatic neo-Romanticism of the misunderstood artist, while criticizing her characters' "isolated rejection of democratic society".[218]

Popular interest[]

With over 30 million copies sold as of 2015, Rand's books continue to be read widely.[g] A survey conducted for the Library of Congress and the Book-of-the-Month Club in 1991 asked club members to name the most influential book in their lives. Rand's Atlas Shrugged was the second most popular choice, after the Bible.[222] Although Rand's influence has been greatest in the United States, there has been international interest in her work.[223][224]

Rand's contemporary admirers included fellow novelists, like Ira Levin, Kay Nolte Smith and L. Neil Smith; she has influenced later writers like Erika Holzer and Terry Goodkind.[225] Other artists who have cited Rand as an important influence on their lives and thought include comic book artist Steve Ditko[226] and musician Neil Peart of Rush,[227] although he later distanced himself. Rand provided a positive view of business and subsequently many business executives and entrepreneurs have admired and promoted her work.[228] John Allison of BB&T and Ed Snider of Comcast Spectacor have funded the promotion of Rand's ideas.[229][230] Mark Cuban (owner of the Dallas Mavericks) as well as John P. Mackey (CEO of Whole Foods), among others, have said they consider Rand crucial to their success.[231]

Television shows including animated sitcoms, live-action comedies, dramas, and game shows, as well as movies and video games have referred to Rand and her works.[232][233] Throughout her life she was the subject of many articles in popular magazines,[234] as well as book-length critiques by authors such as the psychologist Albert Ellis[235] and Trinity Foundation president John W. Robbins.[236] Rand, or characters based on her, figure prominently (in positive and negative lights) in literary and science fiction novels by prominent American authors.[237] Nick Gillespie, former editor-in- chief of Reason, remarked that, "Rand's is a tortured immortality, one in which she's as likely to be a punch line as a protagonist. Jibes at Rand as cold and inhuman run through the popular culture."[238] Two movies have been made about Rand's life. A 1997 documentary film, Ayn Rand: A Sense of Life, was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.[239] The Passion of Ayn Rand, a 1999 television adaptation of the book of the same name, won several awards.[240] Rand's image also appears on a 1999 U.S. postage stamp illustrated by artist Nick Gaetano.[241]

Rand's works have found a foothold in classrooms.[242] Since 2002, the Ayn Rand Institute has provided free copies of Rand's novels to high school teachers who promise to include the books in their curriculum.[243] The Institute had distributed 4.5 million copies in the U.S. and Canada by the end of 2020.[221] In 2017, Rand was added to the required reading list for the A Level Politics exam in the United Kingdom.[244]

Political influence[]

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism |

|---|

|

Although she rejected the labels "conservative" and "libertarian",[245][246] Rand has had a continuing influence on right-wing politics and libertarianism.[14][15] Rand is often considered one of the three most important women (along with Rose Wilder Lane and Isabel Paterson) in the early development of modern American libertarianism.[247][248] David Nolan, one founder of the Libertarian Party, said that "without Ayn Rand, the libertarian movement would not exist".[249] In his history of that movement, journalist Brian Doherty described her as "the most influential libertarian of the twentieth century to the public at large".[222] Historian Jennifer Burns referred to her as "the ultimate gateway drug to life on the right".[14]

The political figures who cite Rand as an influence are usually conservatives (often members of the Republican Party),[250] despite Rand taking some atypical positions for a conservative, like being pro-choice and an atheist.[251] She faced intense opposition from William F. Buckley Jr. and other contributors to the conservative National Review magazine, which published numerous criticisms of her writings and ideas.[252] Nevertheless, a 1987 article in The New York Times referred to her as the Reagan administration's "novelist laureate".[253] Republican congressmen and conservative pundits have acknowledged her influence on their lives and have recommended her novels.[254][255][256][257] She has influenced some conservative politicians outside the U.S., such as Sajid Javid in the United Kingdom,[258] Siv Jensen in Norway,[259] and Ayelet Shaked in Israel.[260]

The financial crisis of 2007–2008 spurred renewed interest in her works, especially Atlas Shrugged, which some saw as foreshadowing the crisis.[261][262][263] Opinion articles compared real-world events with the novel's plot.[250][263] Signs mentioning Rand and her fictional hero John Galt appeared at Tea Party protests.[262] There was increased criticism of her ideas, especially from the political left. Critics blamed the economic crisis on her support of selfishness and free markets, particularly through her influence on Alan Greenspan.[257] In 2015, Adam Weiner said that through Greenspan, "Rand had effectively chucked a ticking time bomb into the boiler room of the US economy".[264] Lisa Duggan said that Rand's novels had "incalculable impact" in encouraging the spread of neoliberal political ideas.[265] In 2021, Cass Sunstein said Rand's ideas could be seen in the tax and regulatory policies of the Trump administration, which he attributed to the "enduring influence" of Rand's fiction.[266]

Academic reaction[]

During Rand's lifetime, her work received little attention from academic scholars.[16] Since her death, interest in her work has increased gradually.[267][268] In 2009, historian Jennifer Burns identified "three overlapping waves" of scholarly interest in Rand, including "an explosion of scholarship" since the year 2000.[269] However, as of that same year, few universities included Rand or Objectivism as a philosophical specialty or research area, with many literature and philosophy departments dismissing her as a pop culture phenomenon rather than a subject for serious study.[270] From 2002 to 2012, over 60 colleges and universities accepted grants from the charitable foundation of BB&T Corporation that required teaching Rand's ideas or works; in some cases, the grants were controversial or even rejected because of the requirement to teach about Rand.[271][272] In 2020, media critic Eric Burns said that, "Rand is surely the most engaging philosopher of my lifetime", [273] but "nobody in the academe pays any attention to her, neither as an author nor a philosopher.[274] That same year, the editor of a collection of critical essays about Rand said academics who disapproved of her ideas had long held "a stubborn resolve to ignore or ridicule" her work,[275] but he believed more academic critics were engaging with her work in recent years.[12]

To her ideas[]

In 1967, John Hospers discussed Rand's ethical ideas in the second edition of his textbook, An Introduction to Philosophical Analysis. That same year, Hazel Barnes included a chapter critiquing Objectivism in her book An Existentialist Ethics.[276] When the first full-length academic book about Rand's philosophy appeared in 1971, its author declared writing about Rand "a treacherous undertaking" that could lead to "guilt by association" for taking her seriously.[277] A few articles about Rand's ideas appeared in academic journals before her death in 1982, many of them in The Personalist.[278] One of these was "On the Randian Argument" by libertarian philosopher Robert Nozick, who criticized her meta-ethical arguments.[176][279] Other philosophers, writing in the same publication, argued that Nozick misstated Rand's case.[278] In an article responding to Nozick, Douglas Den Uyl and Douglas B. Rasmussen defended her positions, but described her style as "literary, hyperbolic and emotional".[280]

The Philosophic Thought of Ayn Rand, a 1984 collection of essays about Objectivism edited by Den Uyl and Rasmussen, was the first academic book about Rand's ideas published after her death.[236] In one essay, political writer Jack Wheeler wrote that despite "the incessant bombast and continuous venting of Randian rage", Rand's ethics are "a most immense achievement, the study of which is vastly more fruitful than any other in contemporary thought".[281] In 1987, Allan Gotthelf, George Walsh, and David Kelley co-founded the Ayn Rand Society, a group affiliated with the American Philosophical Association.[282][283]

In a 1995 entry about Rand in Contemporary Women Philosophers, Jenny A. Heyl described a divergence in how different academic specialties viewed Rand. She said that Rand's philosophy "is regularly omitted from academic philosophy. Yet, throughout literary academia, Ayn Rand is considered a philosopher."[284] Writing in the 1998 edition of the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, political theorist Chandran Kukathas summarized the mainstream philosophical reception of her work in two parts. He said most commentators view her ethical argument as an unconvincing variant of Aristotle's ethics, and her political theory "is of little interest" because it is marred by an "ill-thought out and unsystematic" effort to reconcile her hostility to the state with her rejection of anarchism.[3] The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies, a multidisciplinary, peer-reviewed academic journal devoted to the study of Rand and her ideas, was established in 1999. R. W. Bradford, Stephen D. Cox, and Chris Matthew Sciabarra were its founding co-editors.[285]

In a 2010 essay for the Cato Institute, libertarian philosopher Michael Huemer argued very few people find Rand's ideas convincing, especially her ethics. He attributed the attention she receives to her being a "compelling writer", especially as a novelist, noting that Atlas Shrugged outsells Rand's non-fiction works and the works of other philosophers of classical liberalism.[286] In 2012, the Pennsylvania State University Press agreed to take over publication of The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies,[287] and the University of Pittsburgh Press launched an "Ayn Rand Society Philosophical Studies" series based on the Society's proceedings.[288] That same year, political scientist Alan Wolfe dismissed Rand as a "nonperson" among academics.[13] The Fall 2012 update to the entry about Rand in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy said that "only a few professional philosophers have taken her work seriously".[4]

To her fiction[]

Academic consideration of Rand as a literary figure during her life was even more limited than the discussion of her philosophy. Mimi Reisel Gladstein could not find any scholarly articles about Rand's novels when she began researching her in 1973, and only three such articles appeared during the rest of the 1970s.[289] Since her death, scholars of English and American literature have continued largely to ignore her work,[290] although attention to her literary work has increased since the 1990s.[291] Several academic book series about important authors cover Rand and her works. These include Twayne's United States Authors (Ayn Rand by James T. Baker), Twayne's Masterwork Studies (The Fountainhead: An American Novel by Den Uyl and Atlas Shrugged: Manifesto of the Mind by Gladstein), and Re-reading the Canon (Feminist Interpretations of Ayn Rand, edited by Gladstein and Sciabarra), as well as in popular study guides like CliffsNotes and SparkNotes.[292] In The Literary Encyclopedia entry for Rand written in 2001, John David Lewis declared that "Rand wrote the most intellectually challenging fiction of her generation."[293] In 2019, Lisa Duggan described Rand's fiction as popular and influential on many readers, despite being easy to criticize for "her cartoonish characters and melodramatic plots, her rigid moralizing, her middle- to lowbrow aesthetic preferences ... and philosophical strivings".[294]

Objectivist movement[]

After the closure of the Nathaniel Branden Institute, the Objectivist movement continued in other forms. In the 1970s, Leonard Peikoff began delivering courses on Objectivism.[295] In 1979, Objectivist writer Peter Schwartz started a newsletter called The Intellectual Activist, which Rand endorsed.[296][297] She also endorsed The Objectivist Forum, a bimonthly magazine founded by Objectivist philosopher Harry Binswanger, which ran from 1980 to 1987.[298]

In 1985, Peikoff worked with businessman Ed Snider to establish the Ayn Rand Institute, a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting Rand's ideas and works. In 1990, after an ideological disagreement with Peikoff, philosopher David Kelley founded the Institute for Objectivist Studies, now known as The Atlas Society.[299][300] In 2001, historian John McCaskey organized the Anthem Foundation for Objectivist Scholarship, which provides grants for scholarly work on Objectivism in academia.[301]

Selected works[]

Fiction and drama:

- Night of January 16th (performed 1934, published 1968)

- We the Living (1936, revised 1959)

- Anthem (1938, revised 1946)

- The Unconquered (performed 1940, published 2014)

- The Fountainhead (1943)

- Atlas Shrugged (1957)

- The Early Ayn Rand (1984)

- Ideal (2015)

Non-fiction:

- For the New Intellectual (1961)

- The Virtue of Selfishness (1964)

- Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal (1966, expanded 1967)

- The Romantic Manifesto (1969, expanded 1975)

- The New Left (1971, expanded 1975)

- Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology (1979, expanded 1990)

- Philosophy: Who Needs It (1982)

- Letters of Ayn Rand (1995)

- Journals of Ayn Rand (1997)

Notes[]

- ^ Russian: Алиса Зиновьевна Розенбаум, [aˈlʲɪsa zʲɪˈnovʲɪvnə rəzʲɪnˈbaʊm]. Most sources transliterate her given name as either Alisa or Alissa.[1]

- ^ Rand said Ayn was adapted from a Finnic name.[36] Some biographical sources question this, suggesting it may come from a nickname based on the Hebrew word עין (ayin, meaning 'eye').[37] Letters from Rand's family do not use such a nickname for her.[38]

- ^ Rand's immigration papers anglicized her given name as Alice,[41] so her legal married name became Alice O'Connor, but she did not use that name publicly or with friends.[46][47]

- ^ In 1941, Paramount Pictures produced a movie loosely based on the play. Rand did not participate in the production and was highly critical of the result.[53][54]

- ^ In 1942, the novel was adapted without Rand's permission into a pair of Italian films, Noi vivi and Addio, Kira. After Rand's post-war legal claims over the piracy were settled, her attorney purchased the negatives. The films were re-edited with Rand's approval and released as We the Living in 1986.[58]

- ^ A condensed version of the unfinished book was published as an essay titled "The Only Path to Tomorrow" in the January 1944 issue of Reader's Digest.

- ^ This total includes 3.6 million copies purchased for free distribution to schools by the Ayn Rand Institute (ARI), but does not include editions in languages other than English.[220] By 2020, the total for ARI's free distribution programs had increased to 4.5 million.[221]

References[]

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 121.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Kukathas 1998, p. 55.

- ^ a b c d e f Badhwar & Long 2020.

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, p. 298.

- ^ Gotthelf 2000, p. 91.

- ^ a b Gotthelf 2000, pp. 91–92.

- ^ a b Sciabarra 1995, pp. 266–267.

- ^ a b O'Neill 1977, pp. 18–20.

- ^ a b Sciabarra 1995, pp. 12, 118.

- ^ a b c d Gladstein 1999, pp. 117–119.

- ^ a b Cocks 2020, p. 15.

- ^ a b Murnane 2018, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Burns 2009, p. 4.

- ^ a b Gladstein 2009, pp. 107–108, 124.

- ^ a b Sciabarra 1995, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. xiii.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, p. 68.

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, pp. 69, 367–368.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 2.

- ^ Branden 1986, pp. 35–39.

- ^ Britting 2004, pp. 14–20.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, p. 77.

- ^ Sciabarra 1999, pp. 5–8.

- ^ Lennox, James G. "Who Sets the Tone for a Culture?' Ayn Rand's Approach to the History of Philosophy". In Gotthelf & Salmieri 2016, p. 325.

- ^ Britting 2004, pp. 17–18, 22–24.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 47.

- ^ Britting 2004, p. 24.

- ^ Sciabarra 1999, p. 1.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Britting 2004, p. 33.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 7.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 55.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 19, 301.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 55–57.

- ^ Milgram, Shoshana. "The Life of Ayn Rand: Writing, Reading, and Related Life Events". In Gotthelf & Salmieri 2016, p. 39.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b Heller 2009, p. 53.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 57–60.

- ^ Britting 2004, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Britting 2004, p. 39.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 71.

- ^ Milgram, Shoshana. "The Life of Ayn Rand: Writing, Reading, and Related Life Events". In Gotthelf & Salmieri 2016, p. 24.

- ^ Branden 1986, p. 72.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 96–98.

- ^ Britting 2004, pp. 43–44, 52.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 22.

- ^ Britting 2004, pp. 40, 42.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 76, 92.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 78.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 87.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Ralston, Richard E. "Publishing We the Living". In Mayhew 2004, p. 141.

- ^ Britting, Jeff. "Adapting We the Living". In Mayhew 2004, p. 164.

- ^ Britting, Jeff. "Adapting We the Living". In Mayhew 2004, pp. 167–176.

- ^ Ralston, Richard E. "Publishing We the Living". In Mayhew 2004, p. 143.

- ^ Rand 1995, p. xviii.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 50.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 102.

- ^ Ralston, Richard E. "Publishing Anthem". In Mayhew 2005a, pp. 24–27.

- ^ Britting 2004, p. 57.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 114.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 249.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 75–78.

- ^ Britting 2004, pp. 61–78.

- ^ Britting 2004, pp. 58–61.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 85.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 89.

- ^ a b Burns 2009, p. 178.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 304–305.

- ^ Doherty 2007, p. 149.

- ^ Britting 2004, pp. 68–71.

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, p. 112.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 171.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 100–101, 123.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Mayhew 2005b, pp. 91–93, 188–189.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 125.

- ^ Mayhew 2005b, p. 83.

- ^ Britting 2004, p. 71.

- ^ Branden 1986, p. 181.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 240–243.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 256–259.

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, p. 113.

- ^ Mayhew 2005b, p. 78.

- ^ Salmieri, Gregory. "Atlas Shrugged on the Role of the Mind in Man's Existence". In Mayhew 2009, p. 248.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 42.

- ^ McConnell 2010, p. 507.

- ^ Stolyarov II, G. "The Role and Essence of John Galt's Speech in Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged". In Younkins 2007, p. 99.

- ^ a b Burns 2009, p. 2.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 303–306.

- ^ Younkins 2007, p. 1.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 303.

- ^ Doherty 2007, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 329.

- ^ a b Burns 2009, p. 235.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 232–233.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Doherty 2007, p. 235.

- ^ Branden 1986, pp. 315–316.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 14.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 16.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 228–229, 265.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 352.

- ^ Rand 2005, p. 96.

- ^ a b Burns 2009, p. 266.

- ^ Thompson, Stephen. "Topographies of Liberal Thought: Rand and Arendt and Race". In Cocks 2020, p. 237.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 362, 519.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 204–206.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 322–323.

- ^ Britting 2004, p. 101.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 374–375.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 378–379.

- ^ Branden 1986, pp. 386–389.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 391–393.

- ^ McConnell 2010, pp. 520–521.

- ^ Weiss 2012, p. 62.

- ^ Branden 1986, pp. 392–395.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 406.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 410.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 405, 410.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 400.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 179.

- ^ Britting, Jeff. "Adapting The Fountainhead to Film". In Mayhew 2006, p. 96.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 26.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 27.

- ^ Torres & Kamhi 2000, p. 64.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 64.

- ^ Duggan 2019, p. 44.

- ^ Wilt, Judith. "The Romances of Ayn Rand". In Gladstein & Sciabarra 1999, pp. 183–184

- ^ Britting 2004, pp. 17, 22.

- ^ Torres & Kamhi 2000, p. 59.

- ^ Heller 2009, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Grigorovskaya 2018, pp. 315–325.

- ^ Kizilov 2021, p. 106.

- ^ Weiner 2020, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Rosenthal 2004, pp. 220–223.

- ^ Kizilov 2021, p. 109.

- ^ Rosenthal 2004, pp. 200–206.

- ^ Gladstein, Mimi Reisel. "Ayn Rand's Cinematic Eye". In Younkins 2007, pp. 109–111.

- ^ Rand 1992, pp. 1170–1171.

- ^ Gladstein & Sciabarra 1999, p. 2.

- ^ Den Uyl, Douglas J. & Rasmussen, Douglas B. "Ayn Rand's Realism". In Den Uyl & Rasmussen 1986, pp. 3–20.

- ^ Rheins, Jason G. "Objectivist Metaphysics: The Primacy of Existence". In Gotthelf & Salmieri 2016, p. 260.

- ^ Peikoff 1991, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Gotthelf 2000, p. 54.

- ^ Rand 1964, p. 22.

- ^ Rand 1982, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Salmieri & Gotthelf 2005, p. 1997.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Rand 1964, p. 30.

- ^ Rand 1964, p. 25.

- ^ Rand 1992, p. 1023.

- ^ Peikoff 1991, pp. 313–320.

- ^ Peikoff 1991, p. 369.

- ^ Peikoff 1991, p. 367.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 174–177, 209, 230–231.

- ^ Doherty 2007, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 268–269.

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Torres & Kamhi 2000, p. 26.

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Gotthelf 2000, p. 93.

- ^ Rand 2005, p. 166.

- ^ Salmieri, Gregory. "The Objectivist Epistemology". In Gotthelf & Salmieri 2016, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Rand 1971, p. 1.

- ^ Den Uyl & Rasmussen 1986, p. 165.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, pp. 100, 115.

- ^ a b Sciabarra 1995, p. 240.

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, p. 235.

- ^ Baker 1987, pp. 140–142.

- ^ Khawaja 2014, pp. 211–213.

- ^ Miller, Fred D., Jr. & Mossoff, Adam. "Ayn Rand’s Theory of Rights: An Exposition and Response to Critics". In Salmieri & Mayhew 2019, pp. 135–142

- ^ Miller, Fred D., Jr. & Mossoff, Adam. "Ayn Rand’s Theory of Rights: An Exposition and Response to Critics". In Salmieri & Mayhew 2019, pp. 146–148

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 116.

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, pp. 186–189.

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, p. 12.

- ^ Podritske & Schwartz 2009, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Murray 2010.

- ^ a b Heller 2009, p. 42.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 16, 22.

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, pp. 100–106.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Duggan 2019, p. 3.

- ^ Sciabarra 1998, pp. 136, 138–139.

- ^ Sciabarra 1998, p. 135.

- ^ Loiret-Prunet, Valerie. "Ayn Rand and Feminist Synthesis: Rereading We the Living". In Gladstein & Sciabarra 1999, p. 97.

- ^ Sheaffer, Robert. "Rereading Rand on Gender in the Light of Paglia". In Gladstein & Sciabarra 1999, p. 313.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 41, 68.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 303–304.

- ^ Sciabarra 1998, pp. 135, 137–138.

- ^ Mayhew, Robert. "We the Living '36 and '59". In Mayhew 2004, p. 205.

- ^ Rand 1971, p. 4.

- ^ Salmieri, Gregory. "An Introduction to the Study of Ayn Rand". In Gotthelf & Salmieri 2016, p. 14.

- ^ Walsh 2000.

- ^ Seddon 2003, pp. 63–81.

- ^ Branden 1986, pp. 122–124.

- ^ Berliner, Michael S. "Reviews of We the Living". In Mayhew 2004, pp. 147–151.

- ^ Berliner, Michael S. "Reviews of Anthem". In Mayhew 2005a, pp. 55–60.

- ^ a b c Berliner, Michael S. "The Fountainhead Reviews". In Mayhew 2006, pp. 77–82.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 152.

- ^ Pruette 1943, p. BR7.

- ^ a b Berliner, Michael S. "The Atlas Shrugged Reviews". In Mayhew 2009, pp. 133–137.

- ^ Chambers 1957, p. 594.

- ^ Chambers 1957, p. 596.

- ^ a b Gladstein 1999, p. 119.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Hook 1961, p. 28.

- ^ Vidal 1962, p. 234.

- ^ Rothstein 2005.

- ^ Cocks 2020, p. 29.

- ^ Salmieri, Gregory. "An Introduction to the Study of Ayn Rand". In Gotthelf & Salmieri 2016, p. 3.

- ^ a b "Ayn Rand Institute Annual Report 2020". Ayn Rand Institute. December 20, 2020. p. 17 – via Issuu.

- ^ a b Doherty 2007, p. 11.

- ^ Gladstein 2003, pp. 384–386.

- ^ Murnane 2018, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Riggenbach 2004, pp. 91–144.

- ^ Sciabarra 2004, pp. 8–11.

- ^ Sciabarra 2002, pp. 161–185.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 168–171.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 298.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. 412.

- ^ Rubin 2007.

- ^ Sciabarra 2004, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 282.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 110–111.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 98.

- ^ a b Gladstein 1999, p. 101.

- ^ Sciabarra 2004, p. 3.

- ^ Chadwick & Gillespie 2005, at 1:55.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 128.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 122.

- ^ Wozniak 2001, p. 380.

- ^ Salmieri, Gregory. "An Introduction to the Study of Ayn Rand". In Gotthelf & Salmieri 2016, p. 4.

- ^ Duffy 2012.

- ^ Wang 2017.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 258.

- ^ Weiss 2012, p. 55.

- ^ Burns 2015, p. 746.

- ^ Brühwiler 2021, p. 88.

- ^ Branden 1986, p. 414.

- ^ a b Doherty 2009, p. 54.

- ^ Weiss 2012, p. 155.

- ^ Burns 2004, pp. 139, 243.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 279.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 124.

- ^ Heller 2009, p. xi.

- ^ Doherty 2009, p. 51.

- ^ a b Burns 2009, p. 283.

- ^ Elgot 2018.

- ^ Rudoren 2015.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 283–284.

- ^ a b Doherty 2009, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b Gladstein 2009, p. 125.

- ^ Weiner 2020, p. 2.

- ^ Duggan 2019, p. xiii.

- ^ Sunstein 2021, pp. 145–146.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, pp. 114–122.

- ^ Salmieri & Gotthelf 2005, p. 1995.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 295–296.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 116.

- ^ Flaherty 2015.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, pp. 116–117.

- ^ Burns 2020, p. 261.

- ^ Burns 2020, p. 259.

- ^ Cocks 2020, p. 11.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 188, 325.

- ^ O'Neill 1977, p. 3.

- ^ a b Gladstein 1999, p. 115.

- ^ Nozick 1971, pp. 282–304.

- ^ Den Uyl & Rasmussen 1978, p. 203.

- ^ Wheeler, Jack. "Rand and Aristotle". In Den Uyl & Rasmussen 1986, p. 96.

- ^ Gotthelf 2000, pp. 2, 25.

- ^ Thomas 2000, p. 17.

- ^ Heyl 1995, p. 223.

- ^ Sciabarra 2012, p. 184.

- ^ Huemer 2010.

- ^ Sciabarra 2012, p. 183.

- ^ Seddon 2014, p. 75.

- ^ Gladstein 2003, pp. 373–374, 379–381.

- ^ Gladstein 2003, p. 375.

- ^ Gladstein 2003, pp. 384–391.

- ^ Gladstein 2003, pp. 382–389.

- ^ Lewis 2001.

- ^ Duggan 2019, p. 4.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 249.

- ^ Sciabarra 1995, p. 385.

- ^ Burns 2009, p. 276.

- ^ Gladstein 1999, p. 79.

- ^ Burns 2009, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, pp. 19, 114.

- ^ Gladstein 2009, p. 117.

Works cited[]

- Badhwar, Neera & Long, Roderick T. (Fall 2020). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Ayn Rand". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved May 3, 2021.

- Baker, James T. (1987). Ayn Rand. Twayne's United States Authors Series. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8057-7497-9.

- Branden, Barbara (1986). The Passion of Ayn Rand. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company. ISBN 978-0-385-19171-5.

- Britting, Jeff (2004). Ayn Rand. Overlook Illustrated Lives series. New York: Overlook Duckworth. ISBN 978-1-58567-406-0.

- Brühwiler, Claudia Franziska (2021). Out of a Gray Fog: Ayn Rand's Europe (Kindle ed.). Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-1-79363-686-7.

- Burns, Eric (2020). 1957: The Year that Launched the American Future. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-3995-0.

- Burns, Jennifer (November 2004). "Godless Capitalism: Ayn Rand and the Conservative Movement". Modern Intellectual History. 1 (3): 359–385. doi:10.1017/S1479244304000216. S2CID 145596042.

- Burns, Jennifer (2009). Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-532487-7.

- Burns, Jennifer (December 2015). "The Three 'Furies' of Libertarianism: Rose Wilder Lane, Isabel Paterson, and Ayn Rand". Journal of American History. 102 (3): 746–774. doi:10.1093/jahist/jav504.

- Chadwick, Alex (host) & Gillespie, Nick (contributor) (February 2, 2005). "Book Bag: Marking the Ayn Rand Centennial". Day to Day. National Public Radio.

- Chambers, Whittaker (December 28, 1957). "Big Sister is Watching You". National Review. pp. 594–596.

- Cocks, Nick, ed. (2020). Questioning Ayn Rand: Subjectivity, Political Economy, and the Arts. Palgrave Studies in Literature, Culture and Economics (Kindle ed.). Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-030-53072-3.

- Den Uyl, Douglas & Rasmussen, Douglas (April 1978). "Nozick On the Randian Argument". The Personalist. 59 (2): 184–205.

- Den Uyl, Douglas & Rasmussen, Douglas, eds. (1986) [1984]. The Philosophic Thought of Ayn Rand (paperback ed.). Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-01407-9.

- Doherty, Brian (2007). Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement. New York: Public Affairs Press. ISBN 978-1-58648-350-0.

- Doherty, Brian (December 2009). "She's Back!". Reason. Vol. 41 no. 7. pp. 51–58.

- Duffy, Francesca (August 20, 2012). "Teachers Stocking Up on Ayn Rand Books". Education Week. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- Duggan, Lisa (2019). Mean Girl: Ayn Rand and the Culture of Greed. Oakland, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-96779-3.

- Elgot, Jessica (April 30, 2018). "Who is Sajid Javid, the UK's New Home Secretary?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 30, 2018. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Flaherty, Colleen (October 16, 2015). "Banking on the Curriculum". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- Grigorovskaya, Anastasiya Vasilievna (December 2018). "Ayn Rand's 'Integrated Man' and Russian Nietzscheanism". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 18 (2): 308–334. doi:10.5325/jaynrandstud.18.2.0308. S2CID 172003322.

- Gladstein, Mimi Reisel (1999). The New Ayn Rand Companion. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-30321-0.

- Gladstein, Mimi Reisel (Spring 2003). "Ayn Rand Literary Criticism". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 4 (2): 373–394. JSTOR 41560226.

- Gladstein, Mimi Reisel (2009). Ayn Rand. Major Conservative and Libertarian Thinkers series. New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-4513-1.

- Gladstein, Mimi Reisel & Sciabarra, Chris Matthew, eds. (1999). Feminist Interpretations of Ayn Rand. Re-reading the Canon series. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-01830-0.

- Gotthelf, Allan (2000). On Ayn Rand. Wadsworth Philosophers Series. Belmont, California: Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 978-0-534-57625-7.

- Gotthelf, Allan & Salmieri, Gregory, eds. (2016). A Companion to Ayn Rand. Blackwell Companions to Philosophy. Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8684-1.

- Heller, Anne C. (2009). Ayn Rand and the World She Made. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-51399-9.

- Heyl, Jenny A. (1995). "Ayn Rand (1905–1982)". In Waithe, Mary Ellen (ed.). A History of Women Philosophers: Contemporary Women Philosophers, 1900–Today. 4. Boston: Kluwer Academic. pp. 207–224. ISBN 978-0-7923-2807-0.

- Hook, Sidney (April 9, 1961). "Each Man for Himself". The New York Times Book Review. p. 28.

- Huemer, Michael (January 22, 2010). "Why Ayn Rand? Some Alternate Answers". Cato Unbound. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- Khawaja, Irfan (July 2014). "Randian Egoism: Time to Get High" (PDF). Reason Papers. 36 (1): 211–223.

- Kizilov, Mikhail (July 2021). "Re-reading Rand through a Russian Lens". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 21 (1): 105–110. doi:10.5325/jaynrandstud.21.1.0105. S2CID 235717431.

- Kukathas, Chandran (1998). "Rand, Ayn (1905–82)". In Craig, Edward (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 8. New York: Routledge. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0-415-07310-3.

- Lewis, John David (October 20, 2001). "Ayn Rand". The Literary Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- Mayhew, Robert, ed. (2004). Essays on Ayn Rand's We the Living. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0697-6.

- Mayhew, Robert, ed. (2005a). Essays on Ayn Rand's Anthem. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-1031-7.

- Mayhew, Robert (2005b). Ayn Rand and Song of Russia. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5276-1.

- Mayhew, Robert, ed. (2006). Essays on Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-1578-7.

- Mayhew, Robert, ed. (2009). Essays on Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-2780-3.

- McConnell, Scott (2010). 100 Voices: An Oral History of Ayn Rand. New York: New American Library. ISBN 978-0-451-23130-7.

- Murnane, Ben (2018). Ayn Rand and the Posthuman: The Mind-Made Future. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-319-90853-3.

- Murray, Charles (Spring 2010). "Who Is Ayn Rand?". Claremont Review of Books. Vol. 10 no. 2. Archived from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- Nozick, Robert (Spring 1971). "On the Randian Argument". The Personalist. 52 (2): 282–304.

- O'Neill, William F. (1977) [1971]. With Charity Toward None: An Analysis of Ayn Rand's Philosophy. New York: Littlefield, Adams & Company. ISBN 978-0-8226-0179-1.

- Peikoff, Leonard (1991). Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand. New York: E. P. Dutton. ISBN 978-0-452-01101-4.

- Podritske, Marlene & Schwartz, Peter, eds. (2009). Objectively Speaking: Ayn Rand Interviewed. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-3195-4.

- Pruette, Lorine (May 16, 1943). "Battle Against Evil". The New York Times. p. BR7.

- Rand, Ayn (1964). The Virtue of Selfishness. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-451-16393-6.

- Rand, Ayn (September 1971). "Brief Summary". The Objectivist. Vol. 10 no. 9. pp. 1–4.

- Rand, Ayn (1982). Peikoff, Leonard (ed.). Philosophy: Who Needs It (paperback ed.). New York: Signet Books. ISBN 978-0-451-13249-9.

- Rand, Ayn (1992) [1957]. Atlas Shrugged (35th anniversary ed.). New York: E.P. Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-94892-6.

- Rand, Ayn (1995) [1936]. "Foreword". We the Living (60th Anniversary ed.). New York: Dutton. ISBN 978-0-525-94054-8.

- Rand, Ayn (2005). Mayhew, Robert (ed.). Ayn Rand Answers, the Best of Her Q&A. New York: New American Library. ISBN 978-0-451-21665-6.

- Riggenbach, Jeff (Fall 2004). "Ayn Rand's Influence on American Popular Fiction". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 6 (1): 91–144. JSTOR 41560271.

- Rosenthal, Bernice Glatzer (Fall 2004). "The Russian Subtext of Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 6 (1): 195–225. JSTOR 41560275.

- Rothstein, Edward (February 2, 2005). "Considering the Last Romantic, Ayn Rand, at 100". The New York Times. p. E1.

- Rubin, Harriet (September 15, 2007). "Ayn Rand's Literature of Capitalism". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 12, 2011. Retrieved April 15, 2011.

- Rudoren, Jodi (May 15, 2015). "Ayelet Shaked, Israel's New Justice Minister, Shrugs Off Critics in Her Path". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Salmieri, Gregory & Gotthelf, Allan (2005). "Rand, Ayn (1905–82)". In Shook, John R. (ed.). The Dictionary of Modern American Philosophers. 4. London: Thoemmes Continuum. pp. 1995–1999. ISBN 978-1-84371-037-0.

- Salmieri, Gregory & Mayhew, Robert, eds. (2019). Foundations of a Free Society: Reflections on Ayn Rand's Political Philosophy. Ayn Rand Society Philosophical Studies. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 978-0-8229-4548-2.

- Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (1995). Ayn Rand: The Russian Radical. University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-01440-1.

- Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (Fall 1998). "A Renaissance in Rand Scholarship" (PDF). Reason Papers. 23: 132–159.

- Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (Fall 1999). "The Rand Transcript". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 1 (1): 1–26. JSTOR 41560109.

- Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (Fall 2002). "Rand, Rush and Rock". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 4 (1): 161–185. JSTOR 41560208.

- Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (Fall 2004). "The Illustrated Rand". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 6 (1): 1–20. JSTOR 41560268.

- Sciabarra, Chris Matthew (December 2012). "Expanding Boards, Expanding Horizons". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 12 (2): 183–191. JSTOR 41717246.

- Seddon, Fred (2003). Ayn Rand, Objectivists, and the History of Philosophy. Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America. ISBN 978-0-7618-2308-7.

- Seddon, Fred (July 2014). "Ayn Rand Society Philosophical Studies". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 14 (1): 75–79. doi:10.5325/jaynrandstud.14.1.0075. S2CID 169272272.

- Sunstein, Cass R. (2021). This Is Not Normal: The Politics of Everyday Expectations. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-25350-4.

- Thomas, William (April 2000). "Ayn Rand Through Two Lenses". Navigator. Vol. 3 no. 4. pp. 15–19.

- Torres, Louis & Kamhi, Michelle Marder (2000). What Art Is: The Esthetic Theory of Ayn Rand. Chicago: Open Court Publishing. ISBN 0-8126-9372-8.

- Vidal, Gore (1962). "Two Immoralists: Orville Prescott and Ayn Rand". Rocking the Boat. Boston: Little, Brown. pp. 226–234. OCLC 291123. Reprinted from Esquire, July 1961.

- Walsh, George V. (Fall 2000). "Ayn Rand and the Metaphysics of Kant". The Journal of Ayn Rand Studies. 2 (1): 69–103. JSTOR 41560132.

- Wang, Amy X. (March 27, 2017). "Ayn Rand's 'Objectivist' Philosophy Is Now Required Reading for British Teens". Quartz. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- Wang-naveen, Mala (January 5, 2016). "Er Ayn Rand en politikkens Darth Vader eller en glitrende ledestjerne?" [Is Ayn Rand a Darth Vader of Politics or a Sparkling Guiding Star?]. Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on February 22, 2021. Retrieved June 14, 2021.

- Weiner, Adam (2020) [2016]. How Bad Writing Destroyed the World: Ayn Rand and the Literary Origins of the Financial Crisis (Kindle ed.). London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-5013-1314-1.

- Weiss, Gary (2012). Ayn Rand Nation: The Hidden Struggle for America's Soul. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-59073-4.

- Wozniak, Maurice D., ed. (2001). Krause-Minkus Standard Catalog of U.S. Stamps (5th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 978-0-87349-321-5.

- Younkins, Edward W., ed. (2007). Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged: A Philosophical and Literary Companion. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-5533-6.

External links[]

- Frequently Asked Questions About Ayn Rand from the Ayn Rand Institute

- Works by Ayn Rand at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ayn Rand at Internet Archive

- Works by Ayn Rand at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Rand's papers at The Library of Congress

- Ayn Rand Lexicon – searchable database

- Hicks, Stephen R. C. "Ayn Alissa Rand (1905–1982)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Ayn Rand at IMDb

- Works by Ayn Rand at Open Library

- Ayn Rand at Curlie

- "Writings of Ayn Rand" – from C-SPAN's American Writers: A Journey Through History

- Ayn Rand

- 1905 births

- 1982 deaths

- Writers from Saint Petersburg

- Writers from New York City

- 20th-century American dramatists and playwrights

- 20th-century American novelists

- 20th-century American philosophers

- 20th-century American women writers

- 20th-century atheists

- 20th-century essayists

- 20th-century Russian philosophers

- Activists from New York (state)

- American abortion-rights activists

- American anti-communists

- American anti-fascists

- American atheists

- American atheist writers

- American essayists

- American ethicists

- American people of Russian-Jewish descent

- American political activists

- American political philosophers

- American science fiction writers

- American women activists

- American women dramatists and playwrights

- American women essayists

- American women novelists

- American women philosophers

- American women screenwriters

- American secularists

- American writers of Russian descent

- Aristotelian philosophers

- Atheist philosophers

- Critics of Marxism

- Epistemologists

- Exophonic writers

- Female critics of feminism

- Atheists of the Russian Empire

- Jews of the Russian Empire

- Jewish American dramatists and playwrights

- Jewish American novelists

- Jewish activists

- Jewish anti-communists

- Jewish anti-fascists

- Jewish atheists

- Jewish philosophers

- Jewish women writers

- Metaphysicians

- Novelists from New York (state)

- Objectivists

- Old Right (United States)

- People of the New Deal arts projects

- People with acquired American citizenship

- Philosophers from New York (state)

- Political philosophers

- Pseudonymous women writers

- Dramatists and playwrights of the Russian Empire

- Saint Petersburg State University alumni

- Screenwriters from New York (state)

- Soviet emigrants to the United States

- Women science fiction and fantasy writers

- Burials at Kensico Cemetery

- 20th-century American screenwriters

- Deaths from organ failure

- Disease-related deaths in New York (state)

- 20th-century pseudonymous writers