Barosaurus

| Barosaurus Temporal range: Late Jurassic (Tithonian), 152–150 Ma

PreꞒ

Ꞓ

O

S

D

C

P

T

J

K

Pg

N

↓ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton in rearing posture with a juvenile Kaatedocus siberi, American Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Superfamily: | †Diplodocoidea |

| Family: | †Diplodocidae |

| Genus: | †Barosaurus Marsh, 1890 |

| Species: | †B. lentus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Barosaurus lentus Marsh, 1890

| |

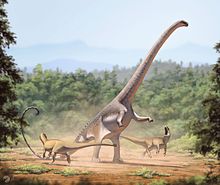

Barosaurus (/ˌbæroʊˈsɔːrəs/ BARR-o-SAWR-əs) was a giant, long-tailed, long-necked, plant-eating dinosaur closely related to the more familiar Diplodocus. Remains have been found in the Morrison Formation from the Upper Jurassic Period of Utah and South Dakota. It is present in stratigraphic zones 2–5.[1]

The composite term Barosaurus comes from the Greek words barys (βαρυς) meaning "heavy" and sauros (σαυρος) meaning "lizard"; thus "heavy lizard".

Description[]

Barosaurus was an enormous animal, with some adults measuring about 25–27 meters (82–89 feet) in length and weighing about 12–20 metric tons (13–22 short tons).[2][3][4] There are some indications of even larger individuals, such as the enormous vertebra from the BYU 9024 specimen, which is 1.37 meters (4.5 ft) long. Assuming it belongs to Barosaurus, this was an animal that was 48 meters (157 ft) long and around 66 metric tons (73 short tons) in weight making it one of the largest known dinosaurs, with a neck length of at least 15 meters (49 ft) according to Mike Taylor.[5] In 2020 Molina-Perez and Larramendi estimated it to be slightly smaller at 45 meters (148 ft) and 60 metric tons (66 short tons).[6] Barosaurus was differently proportioned than its close relative Diplodocus, with a longer neck and shorter tail, but was about the same length overall. It was longer than Apatosaurus, but its skeleton was less robust.[7]

Sauropod skulls are rarely preserved, and scientists have yet to discover a Barosaurus skull. Related diplodocids like Apatosaurus and Diplodocus had long, low skulls with peg-like teeth confined to the front of the jaws.[8]

Most of the distinguishing skeletal features of Barosaurus were in the vertebrae, although a complete vertebral column has never been found. Diplodocus and Apatosaurus both had 15 cervical (neck) and 10 dorsal (trunk) vertebrae, while Barosaurus had only 9 dorsals. A dorsal may have been converted into a cervical vertebra, for a total of 16 vertebrae in the neck. Barosaurus cervicals were similar to those of Diplodocus, but some were up to 50% longer. The neural spines protruding from the top of the vertebrae were neither as tall or as complex in Barosaurus as they were in Diplodocus. In contrast to its neck vertebrae, Barosaurus had shorter caudal (tail) vertebrae than Diplodocus, resulting in a shorter tail. The chevron bones lining the underside of the tail were forked and had a prominent forward spike, much like the closely related Diplodocus. The tail probably ended in a long whiplash, much like Apatosaurus, Diplodocus and other diplodocids, some of which had up to 80 tail vertebrae.[7]

The limb bones of Barosaurus were virtually indistinguishable from those of Diplodocus.[7] Both were quadrupedal, with columnar limbs adapted to support the enormous bulk of the animals. Barosaurus had proportionately longer forelimbs than other diplodocids, although they were still shorter than most other groups of sauropods.[7] There was a single carpal bone in the wrist, and the metacarpals were more slender than those of Diplodocus.[9] Barosaurus feet have never been discovered, but like other sauropods, it would have been digitigrade, with all four feet each bearing five small toes. A large claw adorned the inside digit on the manus (forefoot) while smaller claws tipped the inside three digits of the pes (hindfoot).[7][8]

Classification and systematics[]

Barosaurus is a member of the sauropod family Diplodocidae, and sometimes placed with Diplodocus in the subfamily Diplodocinae.[10] Diplodocids are characterized by long tails with over 70 vertebrae, shorter forelimbs than other sauropods, and numerous features of the skull. Diplodocines like Barosaurus and Diplodocus have slenderer builds and longer necks and tails than apatosaurines, the other subfamily of diplodocids.[7][8][10]

Below is a cladogram of Diplodocinae after Tschopp, Mateus, and Benson (2015).[11]

| Diplodocinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The systematics (evolutionary relationships) of Diplodocidae are becoming better established. Diplodocus has long been regarded as the closest relative of Barosaurus.[7][8][12] Barosaurus is monospecific, containing only the type species, B. lentus, while at least three species belong to the genus Diplodocus.[8] Another diplodocid genus, Seismosaurus, is considered by many paleontologists to be a junior synonym of Diplodocus as a possible fourth species.[13] Tornieria (formerly "Barosaurus" africanus) and Australodocus from the famous Tendaguru Beds of Tanzania in eastern Africa have also been classified as diplodocines.[14][15] With its elongated neck vertebrae, Tornieria may have been particularly closely related to Barosaurus.[14] The other subfamily of diplodocids is Apatosaurinae, which includes Apatosaurus and Supersaurus.[10] The early genus Suuwassea is considered by some to be an apatosaurine,[10] while others regard it as a basal member of the superfamily Diplodocoidea.[16] Diplodocid fossils are found in North America, Europe, and Africa. More distantly related within Diplodocoidea are the families Dicraeosauridae and Rebbachisauridae, found only on the southern continents.[8]

Discovery, naming, and history[]

The first Barosaurus remains were discovered in the Morrison Formation of South Dakota by Ms. E. R. Ellerman, postmistress of Pottsville, and excavated by Othniel Charles Marsh and John Bell Hatcher of Yale University in 1889. Only six tail vertebrae were recovered at that time, forming the type specimen (YPM 429) of a new species, which Marsh named Barosaurus lentus, from the Classical Greek words βαρυς (barys) ("heavy") and σαυρος (sauros) ("lizard"), and the Latin word lentus ("slow").[17] The rest of the type specimen was left in the ground under the protection of the landowner, Ms Rachel Hatch, until it was collected nine years later, in 1898, by Marsh's assistant, . These new remains consisted of vertebrae, ribs and limb bones. In 1896 Marsh had placed Barosaurus in the Atlantosauridae;[18] in 1898 it was by him classified as a diplodocid for the first time.[19] In his last published paper before his death, Marsh named two smaller metatarsals found by Wieland as a second species, Barosaurus affinis,[20] but this has long been considered a junior synonym of B. lentus.[7][8][21]

After the turn of the 20th century, Pittsburgh's Carnegie Museum of Natural History sent fossil hunter Earl Douglass to Utah to excavate the Carnegie Quarry in the area now known as Dinosaur National Monument. Four neck vertebrae, each 1 meter (3 feet) long, were collected in 1912 near a specimen of Diplodocus, but a few years later, William Jacob Holland realized they belonged to a different species.[7] Meanwhile, the type specimen of Barosaurus had finally been prepared at Yale in the winter of 1917 and was fully described by Richard Swann Lull in 1919.[21] Based on Lull's description, Holland referred the vertebrae (CM 1198), along with a second partial skeleton found by Douglass in 1918 (CM 11984), to Barosaurus. This second Carnegie specimen remains in the rock wall at Dinosaur National Monument and was not fully prepared until the 1980s.[7]

The most complete specimen of Barosaurus lentus was excavated from the Carnegie Quarry in 1923 by Douglass, now working for the University of Utah after the death of U.S. Steel founder Andrew Carnegie, who had been financing Douglass' earlier work in Pittsburgh. Material from this specimen was originally spread across three institutions. Most of the back vertebrae, ribs, pelvis, hindlimb and most of the tail stayed at the University of Utah, while the neck vertebrae, some back vertebrae, the shoulder girdle and forelimb were shipped to the National Museum of Natural History in Washington D.C., and a small section of tail vertebrae ended up in the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh. However, in 1929 Barnum Brown arranged for all of the material to be shipped to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, where it remains today. A cast of this specimen (AMNH 6341) was controversially mounted in the lobby of the American Museum, rearing up to defend its young (AMNH 7530, now classified as Kaatedocus siberi[11]) from an attacking Allosaurus fragilis.[7]

More recently, more vertebrae and a pelvis were recovered in South Dakota. This material (SDSM 25210 and 25331) is stored in the collection of the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology in Rapid City.[9]

Darren Naish has noted a common error in books of the late 20th century to depict Barosaurus as a kind of brachiosaur-like short tailed sauropod with raphes on its neck and body, and often curving the upper half of its neck downwards into a U-shape, citing it as an example of a Palaeoart meme.[22][23] This originated with a drawing by Robert Bakker in a 1968 article, in which two Barosaurus appeared to have short tails due to a mix of foreshortening and one obscuring the other.

In 2007, paleontologist was flying to the U.S. Badlands when he discovered reference to a Barosaurus skeleton (ROM 3670) in the collection of the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, where he had recently become a curator. Earl Douglass had excavated this specimen at the Carnegie Quarry in the early 20th century; the ROM acquired it in a 1962 trade with the Carnegie Museum. The specimen was never exhibited and remained in storage until its rediscovery by David Evans 45 years later. He returned to Toronto and searched the storage areas and found many fragments, large and small, of the skeleton. It is now a centrepiece of the ROM's dinosaur exhibit, in the James and Louise Temerty Galleries of the Age of Dinosaurs.[24] At almost 27.5 meters (90 feet) long, the specimen is the largest dinosaur ever to be mounted in Canada.[25] The specimen is about 40% complete. As a skull of Barosaurus has never been found, the ROM specimen wears the head of a Diplodocus.[26] Each bone is mounted on a separate armature so that it can be removed from the skeleton for study and then replaced without disturbing the rest of the skeleton. (See video "Dino Workshop" at reference.)[27] In the rush to put the dinosaur on exhibit within ten weeks of its delivery to in 2500 pieces, not all of the skeletal fragments were mounted. In addition, more bones labeled ROM 3670 are still being found in storage. In future, more may be added to the specimen and it may turn out to be the most complete known.' (See video "Dino Assembly" at reference.)[27] The ROM specimen is nicknamed "Gordo."[25] believes that the ROM's skeleton is the same individual represented by four neck vertebrae labelled "CM 1198" in the collection of the Carnegie Museum.[7]

Discoveries in Africa[]

In 1907, German paleontologist Eberhard Fraas discovered the skeletons of two sauropods on an expedition to the Tendaguru Beds in German East Africa (now Tanzania). He classified both specimens in the new genus Gigantosaurus, with each skeleton representing a new species (G. africanus and G. robustus).[28] However, this genus name had already been given to the fragmentary remains of a sauropod from England.[29] Both species were moved to a new genus, Tornieria, in 1911.[30] Upon further study of these remains and many other sauropod fossils from the hugely productive Tendaguru Beds, Werner Janensch moved the species once again, this time to the North American genus Barosaurus.[31] In 1991, "Gigantosaurus" robustus was recognized as a titanosaur and placed in a new genus, Janenschia, as J. robusta.[32] Meanwhile, many paleontologists suspected "Barosaurus" africanus was also distinct from the North American genus,[7][8] which was confirmed when the material was redescribed in 2006. The African species, although closely related to Barosaurus lentus and Diplodocus from North America, is now once again known as Tornieria africana.[14] A species of Barosaurus was also allegedly identified from the Kadsi Formation in Zimbabwe in 1987.[33] However, this material is poorly preserved and fragmentary and was not adequately diagnosed as such, and so its referral to Barosaurus is doubtful. It may represent Tornieria.[34]

Paleobiology[]

Feeding[]

The structure of the cervical vertebrae of Barosaurus allowed for a significant degree of lateral flexibility in the neck, but restricted vertical flexibility. This suggests a different feeding style for this genus when compared to other diplodocids.[35] Barosaurus swept its neck in long arcs at ground level when feeding, which resembled the strategy that was first proposed by John Martin in 1987.[36] The restriction in vertical flexibility suggests that Barosaurus did not primarily feed on vegetation that was high off the ground.

Paleoecology[]

Barosaurus remains are limited to the Morrison Formation, which is widespread in the western United States between the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains.[7][8] Radiometric dating agrees with biostratigraphic and paleomagnetic studies, indicating that the Morrison was deposited during the Kimmeridgian and early Tithonian stages of the Late Jurassic Period,[37] or approximately 155 to 148 million years ago.[38] Barosaurus fossils are found in late Kimmeridgian to early Tithonian sediments,[11] around 150 million years old.[37]

The Morrison Formation was deposited in floodplains along the edge of the ancient Sundance Sea, an arm of the Arctic Ocean which extended southward to cover the middle of North America as far south as the modern state of Colorado. Due to tectonic uplift to the west, the sea was receding to the north, and had retreated into what is now Canada by the time Barosaurus evolved. The sediments of the Morrison were washed down out of the western highlands, which had been uplifted during the earlier Nevadan orogeny and were now eroding.[37] Very high atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide in the Late Jurassic led to high temperatures around the globe, due to the greenhouse effect. One study, estimating CO2 concentrations of 1120 parts per million, predicted average winter temperatures in western North America of 20 °C (68 °F) and summer temperatures averaging 40–45 °C (104–113 °F).[39] A more recent study suggested even higher CO2 concentrations of up to 3180 parts per million.[40] Warm temperatures that led to significant evaporation year-round, along with possible rain shadow effect from the mountains to the west,[41] led to a semi-arid climate with only seasonal rainfall.[37][42] This formation is similar in age to the Solnhofen limestone Formation in Germany and the Tendaguru Formation in Tanzania. In 1877 this formation became the center of the Bone Wars, a fossil-collecting rivalry between early paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope.

The Morrison Formation records an environment and time dominated by gigantic sauropod dinosaurs such as Camarasaurus, Diplodocus, Apatosaurus and Brachiosaurus. Dinosaurs that lived alongside Barosaurus included the herbivorous ornithischians Camptosaurus, Dryosaurus, Stegosaurus and Othnielosaurus. Predators in this paleoenvironment included the theropods Saurophaganax, Torvosaurus, Ceratosaurus, Marshosaurus, Stokesosaurus, Ornitholestes and[43] Allosaurus accounted for 70 to 75% of theropod specimens and was at the top trophic level of the Morrison food web.[44] Other vertebrates that shared this paleoenvironment included ray-finned fishes, frogs, salamanders, turtles, sphenodonts, lizards, terrestrial and aquatic crocodylomorphans, and several species of pterosaur. Early mammals were present such as docodonts, multituberculates, symmetrodonts, and triconodonts. The flora of the period has been revealed by fossils of green algae, fungi, mosses, horsetails, cycads, ginkgoes, and several families of conifers. Vegetation varied from river-lining forests of tree ferns, and ferns (gallery forests), to fern savannas with occasional trees such as the Araucaria-like conifer Brachyphyllum.[45]

Assistant Curator David Evans mounted the ROM specimen conservatively, with a relatively low head to give the dinosaur moderate blood pressure.[26] The extremely long neck, 10 meters (30 feet) may have developed to enable Barosaurus to feed over a wide area without moving around; it may also have enabled the dinosaurs to radiate excess body heat. Evans suggests that sexual selection might have favoured those with longer necks. (See video "Neck Impossible" at reference.)[27]

References[]

- ^ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327-329.

- ^ Seebacher, Frank. (2001). "A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (1): 51–60. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.462.255. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2001)021[0051:ANMTCA]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Henderson, Donald (2013). "Sauropod Necks: Are They Really for Heat Loss?". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e77108. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...877108H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0077108. PMC 3812985. PMID 24204747.

- ^ Paul, G.S., 2016, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs 2nd edition, Princeton University Press p. 213

- ^ "The size of the BYU 9024 animal". June 16, 2019.

- ^ Molina-Perez & Larramendi (2020). Dinosaur Facts and Figures: The Sauropods and Other Sauropodomorphs. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 36.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n McIntosh, John S. (2005). "The genus Barosaurus Marsh (Sauropoda, Diplodocidae)". In Tidwell, Virginia; Carpenter, Ken (eds.). Thunder-lizards: The Sauropod Dinosaurs. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 38–77. ISBN 978-0-253-34542-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Upchurch, Paul; Barrett, Paul M.; Dodson, Peter (2004). "Sauropoda". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 259–322. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Foster, John R. (1996). "Sauropod dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Black Hills, South Dakota and Wyoming". Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming. 31 (1): 1–25. Archived from the original on June 21, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Lovelace, David M.; Hartman, Scott A.; Wahl, William R. (2007). "Morphology of a specimen of Supersaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, and a re-evaluation of diplodocid phylogeny" (PDF). Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro. 65 (4): 527–544. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 6, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tschopp, E.; Mateus, O. V.; Benson, R. B. J. (2015). "A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda)". PeerJ. 3: e857. doi:10.7717/peerj.857. PMC 4393826. PMID 25870766.

- ^ Wilson, Jeffrey A. (2002). "Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: critique and cladistic analysis". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 136 (2): 215–275. doi:10.1046/j.1096-3642.2002.00029.x.

- ^ Lucas, Spencer G.; Spielmann, Justin A.; Rinehart, Larry A.; Heckert, Andrew B.; Herne, Matthew C.; Hunt, Adrian P.; Foster, John R.; Sullivan, Robert M. (2006). "Taxonomic status of Seismosaurus hallorum, a Late Jurassic sauropod dinosaur from New Mexico". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36: 149-161.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Remes, Kristian (2006). "Revision of the sauropod genus Tornieria africana (Fraas) and its relevance for sauropod paleobiogeography". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (3): 651–669. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[651:ROTTSD]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Remes, Kristian (2007). "A second Gondwanan diplodocid dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic Tendaguru Beds of Tanzania, East Africa". Palaeontology. 50 (3): 653–667. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00652.x.

- ^ Harris, Jerald D. (2006). "The significance of Suuwassea emilieae (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) for flagellicaudatan intrarelationships and evolution". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 4 (2): 185–198. doi:10.1017/S1477201906001805. S2CID 9646734.

- ^ Marsh, Othniel C. (1890). "Description of new dinosaurian reptiles". American Journal of Science. 3 (39): 81–86. Bibcode:1890AmJS...39...81M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-39.229.81. S2CID 131403178.

- ^ Marsh, O.C. (1896). "The dinosaurs of North America". United States Geological Survey, 16th Annual Report, 1894-95. 55: 133–244.

- ^ Marsh, Othniel C. (1898). "On the families of sauropodous Dinosauria". American Journal of Science. 4 (6): 487–488. Bibcode:1899GeoM....6..157M. doi:10.1017/S0016756800142980.

- ^ Marsh, Othniel C. (1899). "Footprints of Jurassic dinosaurs". American Journal of Science. 4 (7): 227–232. Bibcode:1899AmJS....7..227M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-7.39.227.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lull, Richard S. (1919). "The sauropod dinosaur Barosaurus Marsh: redescription of the type specimens in the Peabody Museum, Yale University". Memoirs of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences. 6: 1–42.

- ^ Naish, Darren (February 10, 2017). "Palaeoart Memes and the Unspoken Status Quo in Palaeontological Popularization". Scientific American. Retrieved April 25, 2020.

- ^ Witton, Mark; Naish, Darren; Conway, John (September 2014). "State of the Palaeoart". Palaeontologia Electronica (17.3.5E). doi:10.26879/145.

- ^ "Massive Barosaurus skeleton discovered at the ROM" (Press release). Royal Ontario Museum. November 13, 2007. Retrieved February 25, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Royal Ontario Museum. ROM Channel: Constructing the Barosaurus. Added 2012-08-28. Accessed 2012-12-11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b National Geographic, Museum Secrets, Episode 3: Royal Ontario Museum, Segment "Lost Dinosaur". Broadcast December 10, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c National Geographic, Museum Secrets, Episode 3: Royal Ontario Museum, Segment "Lost Dinosaur". Video clips.. Broadcast December 10, 2012.

- ^ Fraas, Eberhard (1908). "Ostafrikanische Dinosaurier". Palaeontographica. 55: 105–144.

- ^ Seeley, Harry G. (1869). Index to the fossil remains of Aves, Ornithosauria and Reptilia, from the Secondary system of strata arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell and Co. pp. 143pp.

- ^ Sternfeld, Richard (1911). "Zur Nomenklatur der Gattung Gigantosaurus Fraas". Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin. 1911: 398.

- ^ Janensch, Werner (1922). "Das Handskelett von Gigantosaurus robustus und Brachiosaurus brancai aus den Tendaguru-Schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas". Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie. 1922: 464–480.

- ^ Wild, Rupert (1991). "Janenschia n. g. robusta (E. Fraas 1908) pro Tornieria robusta (E. Fraas 1908) (Reptilia, Saurischia, Sauropodomorpha)". Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde. Serie B (Geologie und Paläontologie). 173: 1–4.

- ^ Raath, M.A.; McIntosh, J.S. (1987). "Sauropod dinosaurs from the central Zambezi Valley, Zimbabwe, and the age of the Kadzi Formation". South African Journal of Geology. 90 (2): 107–119. ISSN 1012-0750.

- ^ Mark B. Goodwin; Randall B. Irmis; Gregory P. Wilson; David G. DeMar Jr.; Keegan Melstrom; Cornelia Rasmussen; Balemwal Atnafu; Tadesse Alemu; Million Alemayehu; Samuel G. Chernet (2019). "The first confirmed sauropod dinosaur from Ethiopia discovered in the Upper Jurassic Mugher Mudstone". Journal of African Earth Sciences. 159: Article 103571. Bibcode:2019JAfES.15903571G. doi:10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2019.103571.

- ^ Taylor, Michael P; Wedel, Mathew J (2013). "The neck of Barosaurus was not only longer but also wider than those of Diplodocus and other diplodocines". PeerJ Preprints. 1: e67v1. doi:10.7287/peerj.preprints.67v1.

- ^ Martin, John. 1987. Mobility and feeding of Cetiosaurus (Saurischia, Sauropoda) – why the long neck? pp. 154–159 in P. J. Currie and E. H. Koster (eds), Fourth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems, Short Papers. Boxtree Books, Drumheller (Alberta). 239 pages.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Turner, Christine E.; Peterson, Fred (2004). "Reconstruction of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation extinct ecosystem—a synthesis". In Turner, Christine E.; Peterson, Fred; Dunagan, Stan P. (eds.). Reconstruction of the Extinct Ecosystem of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. Sedimentary Geology. Sedimentary Geology 167 (3-4): 309-355. 167. pp. 309–355. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2004.01.009.

- ^ Kowallis, Bart J.; Christiansen, Eric H.; Deino, Alan L.; Peterson, Fred; Turner, Christine E.; Kunk, Michael J.; Obradovich, John D. (1998). "The age of the Morrison Formation" (PDF). In Carpenter, Ken; Chure, Daniel J.; Kirkland, James I. (eds.). The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22 (1-4): 235-260. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 24, 2007. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ Moore, George T.; Hayashida, Darryl N.; Ross, Charles A.; Jacobson, Stephen R. (1992). "Paleoclimate of the Kimmeridgian/Tithonian (Late Jurassic) world: I. Results using a general circulation model". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 93 (3–4): 113–150. Bibcode:1992PPP....93..113M. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(92)90186-9.

- ^ Ekart, Douglas D.; Cerling, Thure E.; Montanez, Isabel P.; Tabor, Neil J. (1999). "A 400 million year carbon isotope record of pedogenic carbonate; implications for paleoatmospheric carbon dioxide" (PDF). American Journal of Science. 299 (10): 805–827. Bibcode:1999AmJS..299..805E. doi:10.2475/ajs.299.10.805.

- ^ Demko, Timothy M.; Parrish, Judith T. (1998). "Paleoclimatic setting of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation". In Carpenter, Ken; Chure, Daniel J.; Kirkland, James I. (eds.). The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22 (1-4): 283-296.

- ^ Engelmann, George F.; Chure, Daniel J.; Fiorillo, Anthony R. (2004). "The implications of a dry climate for the paleoecology of the fauna of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation". In Turner, Christine E.; Peterson, Fred; Dunagan, Stan P. (eds.). Reconstruction of the Extinct Ecosystem of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. Sedimentary Geology. Sedimentary Geology 167 (3-4): 297-308. 167. pp. 297–308. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2004.01.008.

- ^ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327-329.

- ^ Foster, John R. (2003). Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 23. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. p. 29.

- ^ Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.

Books:

- McIntosh (2005). "The Genus Barosaurus (Marsh)". In Carpenter, Kenneth; Tidswell, Virginia (eds.). Thunder Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 38–77. ISBN 978-0-253-34542-4.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Barosaurus. |

- Diplodocids

- Late Jurassic dinosaurs of North America

- Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation

- Fossil taxa described in 1890

- Taxa named by Othniel Charles Marsh

- Paleontology in Utah

- Paleontology in South Dakota