Battle of Arracourt

| Battle of Arracourt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Lorraine Campaign of World War II | |||||||

Arracourt commemorative monument | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

George Patton Bruce C. Clarke | Hasso von Manteuffel | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| unknown | 262 tanks & assault guns | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

25 medium tanks 7 tank destroyers[1] |

200 tanks & assault guns lost[2]

| ||||||

The Battle of Arracourt took place between U.S. and German armoured forces near the town of Arracourt, Lorraine, France between 18 and 29 September 1944, during the Lorraine Campaign of World War II. As part of a counteroffensive against recent U.S. advances in France, the German 5th Panzer Army had as its objective the recapture of Lunéville and the elimination of the XII Corps bridgehead over the Moselle River at Dieulouard.[3]

With local superiority in troops and tanks, the Germans anticipated quick defeat of the defending Combat Command A (CCA) of the U.S. 4th Armored Division.[3] With better intelligence, tactics and use of terrain, CCA and the XIX Tactical Air Command defeated two panzer brigades and elements of two panzer divisions over eleven days of battle.[3]

Opposing forces[]

For the battle, German units assembled 262 tanks and assault guns.[2] The German force initially comprised two panzer corps headquarters, the 11th Panzer Division and the 111th and 113th Panzer Brigades. The experienced 11th Panzer Division was short of tanks, having lost most of its complement in earlier fighting; the two panzer brigades had new Panther tanks, but fresh crews with virtually no battle experience and insufficient training. The need to quickly respond to the sudden advance of the 4th Armored Division and a fuel shortage left the crews with little time for training and little proficiency in tactical maneuvering in large, combined arms operations.[4]

Combat Command A (CCA Colonel Bruce C. Clarke) of the U.S. 4th Armored Division (Major General John S. Wood) in XII Corps (Major General Manton S. Eddy) consisted of the 37th Tank Battalion, the 53rd Armored Infantry Battalion, the 66th and 94th Armored Field Artillery Battalions and the 191st Field Artillery Battalion.[5] Also present were elements of the 35th Tank Battalion, the 10th Armored Infantry Battalion, the 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion, the 25th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron, the 24th Armored Engineer Battalion, and the 166th Engineer Combat Battalion.

The 5th Panzer Army outnumbered CCA in tanks and was equipped with Panther tanks, superior to American M4 Sherman tanks in frontal armour protection and main gun range, countered by the U.S. tanks' faster turret traverse and stabilized guns. In close air support, U.S. forces enjoyed an overwhelming advantage. Earlier sorties by U.S. fighter bombers caused some German panzer units to fail to arrive in time for the battle, as they were damaged or destroyed in separate encounters with other Allied forces.[6]

Battle[]

On 18 September, with the weather deteriorating and heavy fog settling in, U.S. tactical air forces were unable to locate and destroy advancing German armored units. However, while shielding the German advance from air observation and attack, the weather also handicapped the 5th Panzer Army. Poor visibility combined with a lack of motorized scouting and reconnaissance units in the new "Panzer Army" formations prevented German armored forces from properly coordinating their attack, which soon degenerated into a disjointed series of intermittent thrusts.[3]

The first German attack, mounted by the 111th Panzer Brigade, fell on the 2nd Mechanized Cavalry Group and the 4th Armored Division's Reserve Command at Lunéville on 18 September 1944.[3] In sharp fighting, the understrength U.S. forces, augmented by reinforcements from both the U.S. 4th and 6th Armored Divisions, managed to beat back the attack, destroying two dozen panzers.[3] Generals Wood and Eddy, believing the Lunéville engagement to be only a local counterattack, initially decided to proceed with a planned corps offensive;[3] however, reports of increased German activity throughout the night of 18–19 September led to postponement of the attack.[3] The Fifth Panzer Army, having failed to take Lunéville quickly, simply bypassed it and began moving north to strike at CCA's exposed position in and around Arracourt. The resulting battle was one of the largest armored engagements ever fought on the Western Front.[3]

CCA's dispositions around Arracourt consisted of a thinly held salient, using an extended outpost line of armored infantry and engineers, supported by tanks, tank destroyers, and artillery.[3] At 08:00 on 19 September, company-sized elements of the 113th Panzer Brigade penetrated CCA outposts on the east and south faces of CCA's salient.[3] Two tank destroyer platoons and a medium tank company engaged the panzers in a running fight that extended into the vicinity of CCA's headquarters, where a battalion of M7 Priest self-propelled howitzers engaged the panzers with close-range direct fire.[3]

Poor tactical deployment of the German tanks soon exposed their weaker side armor to Shermans, which flanked and knocked out 11 panzers using the fog as cover. As 5th Panzer Army was not equipped with integral scouting units, the Germans were forced to advance blindly against the Americans, whose positions were shrouded in thick morning fog.[3] Reinforced with additional tank, infantry and cavalry elements and aided by the Germans' persistence in repeating the same plan of attack, CCA was able to locate and prepare for battle on ground of its own choosing.[3] A combination of concealed defensive positions, command of local terrain elevations, and clever fire-and-maneuver tactics allowed CCA to negate the superior armor and firepower of the German armor.[3][7] While the advancing Germans were continually exposed to American fire, U.S. armor was able to maneuver into favourable defensive positions, staying hidden until the German armour had closed to within effective range then inflicting heavy casualties. The fog that had allowed German forces tactical surprise and protection from U.S. air attack also negated the superior range of their tank guns.[3]

From 20 to 25 September, Fifth Panzer Army ordered the 111th Panzer Brigade and the understrength 11th Panzer Division into a series of disjointed attacks against the Arracourt position.[3] On 20 September, Panther tanks moved towards CCA's headquarters component, and several 4th Armored Division support units were pinned down or trapped by the German advance.[8][9] An Army observation pilot, Major "Bazooka Charlie" Carpenter, took to the air with his bazooka-armed L-4 Cub, USAAF serial number 43-30426 and nicknamed Rosie the Rocketer, to attack the enemy.[9] At first, Carpenter was unable to spot the enemy due to low clouds and heavy fog, which finally lifted around noon.[9] Spotting a company of German Panther tanks advancing towards Arracourt, Carpenter dived through German ground fire in a series of attacks against the German panzers, firing all of his bazooka rockets in repeated passes.[8][9] Returning to base to reload, Carpenter flew two more sorties that afternoon, firing no fewer than sixteen bazooka rockets at German tanks and armored cars, several of which were hit.[8] Carpenter's actions that day were later credited and verified by ground troops with knocking out two Panther tanks and several armored cars, while killing or wounding a dozen or more enemy soldiers,[8][9][10][11] and was eventually credited with destroying six enemy tanks, including two Tiger I heavy tanks.[12][13] Carpenter's actions also forced the German tank formation to retreat to its starting position, in the process enabling a trapped 4th Armored water point support crew to escape capture and destruction.[8][9]

On 21 September, with skies clearing, P-47 Thunderbolts of the 405th Fighter Group, 84th Fighter Wing of the U.S. XIX Tactical Air Command (TAC) were able to begin a relentless series of attacks on German ground forces.[14] In addition to missions of opportunity flown by XIX TAC fighter-bombers, CCA was able to call in tactical air strikes against German panzer concentrations.[3] The 4th Armored's close relationship with the USAAF's XIX TAC and mastery of ground-air tactical coordination was a significant factor in destroying the offensive capability of the German armored formations.[15]

By 24 September, most of the fighting had moved to Château-Salins, where a fierce attack by the of the German First Army nearly overwhelmed 4th Armored's Combat Command B, before being routed by U.S. fighter-bombers.[3] The following day, Third Army received orders to suspend all offensive operations and consolidate its gains.[3] In compliance with corps orders, the entire 4th Armored Division reverted to the defense on 26 September.[3] CCA withdrew 5 miles (8.0 km) to more defensible ground, and CCB, relieved at Château-Salins by the 35th Division, linked up with the right flank of CCA.[3] The Fifth Panzer Army, by now reduced to only 25 tanks, pressed its attacks unsuccessfully for three more days, until clearing weather and increased U.S. air activity forced the Germans to suspend their counteroffensive altogether and begin a retreat towards the German frontier.[3]

Aftermath[]

The Battle of Arracourt was concurrent with the end of Third Army's rapid advance across France, which had been stopped short of entering Germany by Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower's decision to divert fuel supplies to other forces. The delay allowed the German Army to regroup for the defense of the German border on the Siegfried Line. Adolf Hitler, however, was less than pleased with the results of the German offensive, and relieved the commander of Army Group G, Johannes Blaskowitz.

Arracourt was the largest tank battle involving U.S. forces on the Western Front until the Battle of the Bulge, and has been used as an example of how tactical situations and crew quality can be far more important factors in determining the outcome of a tank battle than the technical merits of the tanks themselves.[16][17]

Analysis[]

Steven Zaloga describes the German losses: "Of the 262 tanks and assault guns deployed by the German units in the week of fighting near Arracourt, 86 were destroyed, 114 were damaged or broken down, and only 62 were operational at the end of the month". By comparison "4th Armored Division's Combat Command A, which had borne the brunt of the 5th Panzer Army's counter-offensive at Arracourt, lost 25 tanks and 7 tank destroyers.[1] As a division, the 4th AD lost some 41 M4 medium tanks and 7 M5A1 light tanks during the whole month of September, with casualties of 225 killed and 648 wounded."[18]

While Third Army had succeeded in the early weeks of September in completing a limited advance toward Germany—despite orders to the contrary—the Battle of Arracourt signaled a temporary halt to the U.S. drive in north-eastern France. On 22 September, Third Army commander General George S. Patton was informed that his fuel supplies were being restricted and that he would have to shift to a defensive posture.[19] The fuel was required for other U.S. forces.

A paradox of the Battle of Arracourt is that the Germans believed, despite their heavy losses, that they had succeeded in their objective of stopping the advance of Patton's Third Army, as the Third Army had come to a halt. Generalmajor Friedrich von Mellenthin—Chief of Staff of the 5th Panzer Army—summarised the situation:

Quite apart from Hitler's orders, our attacks on the XIIth Corps at Gremecey and Arracourt appeared to have some justification. When Balck took over Army Group G on 21 September it looked as though the Americans were determined to force their way through to the Saar and the Rhine, and General Patton might well have done so if he had been given a free hand. At that time the West Wall was still unmanned, and no effective defense could have been made there. From our point of view there was much to be said for counterattacking the spearheads of the XIIth Corps to discourage the Americans from advancing farther. Although our attacks were very costly it appeared at the time that they had achieved their purpose, and had effectively checked the American Third Army.

In fact, Patton was compelled to halt by Eisenhower's order of 22 September. [Eisenhower] had decided to accept Montgomery's proposal to make the main effort on the northern flank, clear the approaches to Antwerp, and try to capture the Ruhr before winter. Third Army received categorical orders to stand on the defensive. The rights and wrongs of this strategy do not concern me, but it certainly simplified the problems of Army Group G. We were given a few weeks' grace to rebuild our battered forces and get ready to meet the next onslaught.

— Mellenthin[20]

Robert S. Allen's 1947 work "Lucky Forward", a volume full of praise for General Patton and the Third Army's campaigns in 1944–45, does not mention the Battle of Arracourt. In the face of the initial German attacks, the Third Army was little troubled by them, and concentrated on its own advance on Sarreguemines.[21][22] Subsequently, Patton and his staff had to focus on reorganization, in order to comply with Eisenhower's order to halt their advance but the actions at Arracourt, among others fought by the Third Army in September 1944, contributed to a shift in U.S. perceptions of the campaign:

Yet by the end of September, the expectation of a rapid final offensive into the Reich had faded into a far less substantial hope than it had seemed when the Allies drove headlong across the First World War battlefields a month before. If the Germans could mount at Arracourt the most formidable tank attacks since the battles against the British around Caen, their recovery had exceeded the expectations of even Patton's sober G-2 -- and the West Wall still lay ahead everywhere, and unbroken.

— Weigley[23]

Maps[]

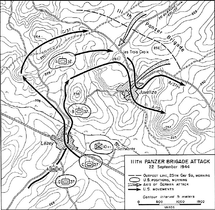

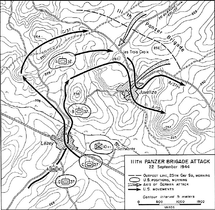

19 September 1944

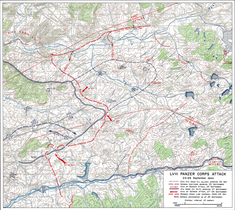

19 September 1944 20 September 1944

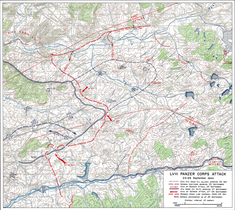

20 September 1944 22 September 1944

22 September 1944 25–29 September 1944

25–29 September 1944

Notes[]

Citations[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gabel, Christopher R., (Dr.), The Lorraine Campaign: An Overview, September-December 1944 Archived 13 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, retrieved 26 October 2011

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zaloga, Steven, Lorraine 1944, Oxford: Osprey Publishing (UK), ISBN 978-1-84176-089-6, (2000), p. 84

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Gabel, Christopher R. (Dr.), The 4th Armored Division in the Encirclement of Nancy, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas (April 1986)

- ^ Zaloga, Duel 13 Panther vs Sherman, Osprey Publishing, pp 14–15

- ^ Combat Command A, 4th Armored Division, 19 September 1944 Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, privateletters.net retrieved 26 October 2011

- ^ Zaloga 2008, Armored Thunderbolt, pp 187–189

- ^ Zaloga 2008 Armored Thunderbolt pp. 184–193

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Gallagher, Wes (2 October 1944). "Charlie Fights Nazi Tanks in Cub Armed With Bazookas", The New York Sun

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Fox, Don M. and Blumenson, Martin, Patton's Vanguard: The United States Army's Fourth Armored Division, McFarland, ISBN 0-7864-3094-X, 9780786430949 (2007), pp. 142–143

- ^ Fountain, Paul (March 1945), "The Maytag Messerschmitts", Flying Magazine, p. 90

- ^ "Puddle-Jumped Panzers", Newsweek, Newsweek Inc., Vol. 24, Part 2 (2 October 1944), p. 31

- ^ "Piper Cub Tank Buster". Popular Science. New York: Popular Science Publishing Company. 146 (2): 84. February 1945. ISSN 0161-7370.

- ^ Carpenter, Leland F, "Piper L-4J Grasshopper", Aviation Enthusiast Corner, Aero Web, archived from the original on 4 September 2011, retrieved 21 October 2011.

- ^ Rust (1967), p. 122

- ^ Rust (1967), p. 122

- ^ Zaloga 2008 Armored Thunderbolt p. 193

- ^ Zaloga 2008 Panther vs. Sherman pp. 67–73

- ^ Zaloga 2008 Armored Thunderbolt pp. 192–193

- ^ Zaloga 2008, p. 192

- ^ von Mellenthin 1971, p. 381-382

- ^ Zaloga 2000, p. 72

- ^ Jarymowicz, p. 237

- ^ Weigley, p. 343

References[]

- Barnes, Richard H. (1982). "Arracourt - September 1944" (PDF). US Army Command and General Staff College, 1982.

A thesis presented to the Faculty of the Command U.S. Army and General Staff College In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Military Art and Science

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Cole, Hugh M., The Lorraine Campaign, Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, 1997. Revised ed. ; previously published in 1950 OCLC 1253758.

- Fox, Don M., "Patton's Vanguard - The United States Army Fourth Armored Division", Jefferson NC: McFarland & Company, Inc. 2003 ISBN 0-7864-1582-7.

- Gabel, Christopher R. (Dr.), The 4th Armored Division in the Encirclement of Nancy, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas (April 1986).

- Jarymowicz, Roman J. (2001). Tank Tactics. Art of War. Boulder: Lynne Rienner. ISBN 978-1-55587-950-1.

- Mellenthin, F. W. von (1971). Panzer Battles. New York: Ballantine, first published by the University of Oklahoma Press, 1956. ISBN 0-345-32158-8.

- Rust, Ken C (1967). The Ninth Air Force in World War II. Fallbrook, CA: Aero Publishers. LCCN 67016454. OCLC 300987379.

- Weigley, Russell F., Eisenhower's Lieutenants, Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1981. OCLC 7748880

- Zaloga, Steven (2000). Lorraine 1944. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-089-6.

- Zaloga, Steven (2008a). Armored Thunderbolt. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole. ISBN 978-0-8117-0424-3.

- Zaloga, Steven (2008b). Panther vs. Sherman: Battle of the Bulge 1944. Oxford: Osprey Publishing (UK). ISBN 978-1-84603-292-9.

External links[]

- Allied advance from Paris to the Rhine

- Meurthe-et-Moselle

- Battles of World War II involving Germany

- Battles of World War II involving the United States

- Tank battles involving the United States

- 1944 in France

- Conflicts in 1944

- Military history of Lorraine

- Tank battles involving Germany

- September 1944 events