Battle of Heilbronn (1945)

| Battle of Heilbronn | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Allied invasion of Germany in the Western Front of the European theatre of World War II | |||||||

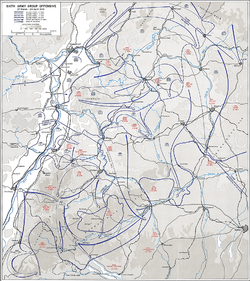

Allied Sixth Army Group Offensive, March–April 1945 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Withers A. Burress | Georg Bochmann | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| 100th Infantry Division |

17th SS Panzergrenadier Division Volksturm units | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

60 killed 250 wounded 112 missing Total: 422[1] | 1,500 captured | ||||||

The Battle of Heilbronn was a nine-day battle in April 1945 during World War II between the United States Army and the German Army for the control of Heilbronn, a mid-sized city on the Neckar River located between Stuttgart and Heidelberg. Despite the impending end of the war, the battle was characterized by very firm German resistance and the presence of various Nazi Party auxiliaries among the regular German troops. Following days of house-to-house combat, troops of the U.S. 100th Infantry Division captured Heilbronn and the U.S. VI Corps continued its march to the southeast.

The German situation[]

The presence of the German First Army's only remaining battleworthy division, the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division, plus imposing river obstacles, gave real substance to the new German line along the Jagst-Neckar crescent. In addition, the First Army commander General Hermann Foertsch had managed to accumulate a sizable conglomeration of other troops, two battalions of an engineer school, several regular engineer battalions, replacement artillery and antiaircraft units, Volkssturm, a few tanks and assault guns, and a miscellany, including several hundred Hitler Youth, belonging to the combat commander of Heilbronn. These troops and remnants of four divisions, plus the panzer grenadiers, were all subordinated to General Bork's[2] XIII Corps. Loose ends of two other divisions, including the 2nd Mountain Division, were positioned on the north wing of General Franz Beyer's LXXX Corps and thus might be used to help defend Heilbronn.

U.S. attack[]

Before daylight on 4 April, the third battalion of the 100th Division's slipped silently across the Neckar in assault boats a mile or so north of Heilbronn, starting from the suburb of Neckargartach.[3] As the men turned south toward the city after daybreak, a German battalion, using, in some cases, tunnels to emerge in the rear of the U.S. troops, counterattacked sharply. The ensuing fight forced the American infantrymen back to within a few hundred feet of the river. There they held, but not until another battalion of the 398th crossed under fire in late afternoon were they able to resume their advance. Even then they could penetrate no deeper than 1,000 yards (910 m), scarcely enough to rid the crossing site of small arms fire. Until the bridgehead could be expanded, engineers had no hope of building a bridge. Later on 4 April, General Burress of the 100th Division had the cross the Neckar just south of the 398th's position.

Although three of the 100th Division's battalions eventually crossed into the little bridgehead north of the city to push south into a collection of factories on the northern outskirts, the going always was slow. Since the crossing site remained under German fire, engineers still had no hope of putting in a bridge. Without close fire support, the infantrymen depended upon artillery on the west bank of the Neckar, but fire was difficult to adjust in the confined factory district. Protected from shelling by sturdy buildings, the Germans seldom surrendered except at the point of a rifle, though many of the Hitler Youth had had enough after only a brief flurry of fanatic resistance.

House to house, room to room, over dead Krauts, through rubbish, under barbed wire, over fences, in the windows and out of doors, sweating, cussing, firing, throwing grenades, charging into blazing houses, shooting through floors and closet doors.

— U.S. soldier of the 399th Infantry Regiment describing combat in Heilbronn[4]

At one point, in response to intense mortar fire, a platoon of Hitler Youth soldiers ran screaming into American lines to surrender while their officers shot at them to make them stop. During the night of 5 April, a battalion of the 397th Infantry crossed the Neckar south of Heilbronn and found resistance at that point just as determined. There engineers had nearly completed a bridge during the afternoon of the 7th when German artillery, controlled by observers in the hills on the east edge of Heilbronn, found the range. Although the engineers at last succeeded early the next morning, less than a company of tanks and two platoons from the 824th Tank Destroyer Battalion had crossed before German shells again knocked out the bridge. Two days later much the same thing happened to a heavy pontoon ferry after it had transported only a few more tanks and tank destroyers across. On 8 April, the U.S. crossed the Neckar to the south of Heilbronn, moving into southern industrial suburbs and the village of Sontheim.

Most of Heilbronn was under U.S. control by 9 April,[5] but not until 12 April was the rubble of Heilbronn cleared of Germans and a bridge built across the Neckar. On that day, the 397th Infantry took two hill summits to the east of the city, nicknamed "Tower Hill" and "Cloverleaf Hill". These actions, coupled with the general advance of all three U.S. regiments, signaled the end of organized German resistance in Heilbronn.

In nine days of fighting, the 100th Division lost 85 men killed and probably three times that number wounded. In the process, men of the 100th captured 1,500 Germans. The U.S. 63rd Division, aided in later stages by tanks of the 10th Armored Division, had in the meantime kept up constant pressure against the enemy's line along the Jagst River, driving southwestward from the vicinity of the Jagst-Tauber land bridge in hope of trapping the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division near the confluence of the Jagst and the Neckar. Although a contingent of armor at last established contact with the 100th Division near Heilbronn on 14 April, the panzer grenadiers had left.

Assessment[]

General Foertsch's hasty but surprisingly strong position along the Jagst-Neckar crescent had required eleven days of often heavy fighting to reduce. Despite the determined resistance, American casualties were relatively light, a daily average for the VI Corps of approximately 230. Yet that number was almost double the number of casualties the corps suffered in the pursuit up to the two rivers.[6] While the German defense had delayed the advance of part of the U.S. VI Corps for almost two weeks, it did not materially impede the advance of the U.S. Army into southern Germany.

Heilbronn itself had been heavily damaged by air raids before the nine-day battle that resulted in the city's capture by U.S. forces, but the urban nature of the battle undoubtedly resulted in even more damage to the city.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ americainwwii.com

- ^ Generalleutnant Max Hermann Ferdinand Bork, 1 January 1899 – 4 July 1973, served in various staff positions before commanding the 47. Volksgrenadierdivision in September 1944, and finally the XIII. Armeekorps on 31 March 1945. Captured near Salzburg and remained a POW until 1 May 1948.

- ^ americainwwii.com, p. 30

- ^ http://www.americainwwii.com/pdfs/stories/heilbronn-one-last-place-to-die.pdf, p. 31

- ^ americainwwii.com p. 35

- ^ Much material in this article copied from The Last Offensive, pp. 415-418, a U.S. Government work in the public domain.

- Charles B. McDonald, The Last Offensive, Chapter XVIII, Washington: GPO, 1973

External links[]

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Government.: Charles B. McDonald, The Last Offensive, Chapter XVIII, Washington: GPO, 1973

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Government.: Charles B. McDonald, The Last Offensive, Chapter XVIII, Washington: GPO, 1973

- Western European Campaign (1944–1945)

- Heilbronn

- April 1945 events

- 1945 in Germany

- Conflicts in 1945