Battle of Okinawa

| Battle of Okinawa | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Pacific Theater of World War II | |||||||

US Marine from the 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines on Wana Ridge provides covering fire with his Thompson submachine gun, 18 May 1945. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Ground Forces: Naval Support: |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Ground units:

Naval units:

|

Ground units:

Naval units:

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

~541,000 in Tenth Army ~183,000 combat troops[3] rising to ~250,000[4]:567 |

~76,000+ Japanese soldiers, ~40,000+ Okinawan conscripts[5] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Materiel: 221 tanks destroyed[11] 12 destroyers sunk 15 amphibious ships sunk 9 other ships sunk 386 ships damaged 763 aircraft[4]:573[12]:473 |

77,166 Japanese soldiers dead[6] over ~30,000 Okinawan conscripts killed ~110,000 killed total (US estimate)[13] More than ~7,000–15000 captured[13] Materiel: 1 battleship sunk 1 light cruiser sunk 5 destroyers sunk 9 other warships sunk 1,430 aircraft lost[14] 27 tanks destroyed 743–1,712 artillery pieces, anti-tank guns, mortars and anti-aircraft guns[12]:91–2 | ||||||

| 40,000–150,000 civilians killed, committed suicide, or went missing out of an estimated prewar population of 300,000[13] | |||||||

| |||||||

The Battle of Okinawa (Japanese: 沖縄戦, Hepburn: Okinawa-sen), codenamed Operation Iceberg,[15]:17 was a major battle of the Pacific War fought on the island of Okinawa by United States Army and United States Marine Corps (USMC) forces against the Imperial Japanese Army.[16] The initial invasion of Okinawa on 1 April 1945, was the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific Theater of World War II.[17][18] The Kerama Islands surrounding Okinawa were preemptively captured on 26 March, (L-6) by the 77th Infantry Division. The 98-day battle lasted from 26 March until 2 July 1945. After a long campaign of island hopping, the Allies were planning to use Kadena Air Base on the large island of Okinawa as a base for Operation Downfall, the planned invasion of the Japanese home islands, 340 mi (550 km) away.

The United States created the Tenth Army, a cross-branch force consisting of the US Army 7th, 27th, 77th and 96th Infantry Divisions with the USMC 1st, 2nd, and 6th Marine Divisions, to fight on the island. The Tenth was unique in that it had its own Tactical Air Force (joint Army-Marine command), and was also supported by combined naval and amphibious forces.

The battle has been referred to as the "typhoon of steel" in English, and tetsu no ame ("rain of steel") or tetsu no bōfū ("violent wind of steel") in Japanese.[19][20] The nicknames refer to the ferocity of the fighting, the intensity of Japanese kamikaze attacks and the sheer numbers of Allied ships and armored vehicles that assaulted the island. The battle was one of the bloodiest in the Pacific, with approximately 160,000 casualties combined: at least 50,000 Allied and 84,166–117,000 Japanese,[21][12]:473–4 including drafted Okinawans wearing Japanese uniforms.[13][6] 149,425 Okinawans were killed, died by suicide or went missing, roughly half of the estimated pre-war 300,000 local population.[6]

In the naval operations surrounding the battle, both sides lost considerable numbers of ships and aircraft, including the Japanese battleship Yamato. After the battle, Okinawa provided a fleet anchorage, troop staging areas, and airfields in proximity to Japan in preparation for a planned invasion of the Japanese home islands.

Order of battle[]

Allied[]

In all, the US Army had over 103,000 soldiers (of these, 38,000+ were non-divisional artillery, combat support and HQ troops, with another 9,000 service troops),[22]:39 over 88,000 Marines and 18,000 Navy personnel (mostly Seabees and medical personnel).[22]:40 At the start of the Battle of Okinawa, US Tenth Army had 182,821 personnel under its command.[22]:40 It was planned that Lieutenant general Simon Bolivar Buckner Jr. would report to Vice admiral Richmond K. Turner until the amphibious phase was completed, after which he would report directly to Admiral Raymond A. Spruance. Total aircraft in the American Navy, Marine and Army Air Force exceeded 3000 over the course of the battle, including fighters, attack aircraft, scout planes, bombers and dive-bombers. The invasion was supported by a fleet consisting of 18 battleships, 27 cruisers, 177 destroyers/destroyer escorts, 39 aircraft carriers (11 fleet carriers, 6 light carriers and 22 escort carriers) and various support and troop transport ships.[23]

The British naval contingent accompanied 251 British naval aircraft, and included a British Commonwealth fleet with Australian, New Zealand and Canadian ships and personnel.[24]

Japanese[]

The Japanese land campaign (mainly defensive) was conducted by the 67,000-strong (77,000 according to some sources) regular 32nd Army and some 9,000 Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) troops at Oroku Naval Base (only a few hundred of whom had been trained and equipped for ground combat), supported by 39,000 drafted local Ryukyuan people (including 24,000 hastily drafted rear militia called Boeitai and 15,000 non-uniformed laborers). The Japanese had used kamikaze tactics since the Battle of Leyte Gulf, but for the first time, they became a major part of the defense. Between the American landing on 1 April and 25 May, seven major kamikaze attacks were attempted, involving more than 1,500 planes.

The 32nd Army initially consisted of the 9th, 24th and 62nd Divisions and the 44th Independent Mixed Brigade. The 9th Division was moved to Taiwan before the invasion, resulting in shuffling of Japanese defensive plans. Primary resistance was to be led in the south by Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima, his chief of staff, Lieutenant General Isamu Chō and his chief of operations, Colonel Hiromichi Yahara. Yahara advocated a defensive strategy, whilst Chō advocated an offensive one.

In the north, Colonel Takehido Udo was in command. The IJN troops were led by Rear Admiral Minoru Ōta. They expected the Americans to land 6–10 divisions against the Japanese garrison of two and a half divisions. The staff calculated that superior quality and numbers of weapons gave each US division five or six times the firepower of a Japanese division. To this, would be added the Americans' abundant naval and air firepower.

Japanese commanders of Okinawa (photographed early in February 1945). In center: (1) Admiral Minoru Ota, (2) Lt. Gen. Mitsuru Ushijima, (3) Lt. Gen. Isamu Cho, (4) Col. Hitoshi Kanayama, (5) Col. Kikuji Hongo, and (6) Col. Hiromichi Yahara

Japanese soldiers arriving on Okinawa

Japanese high school girls wave farewell to a kamikaze pilot departing to Okinawa

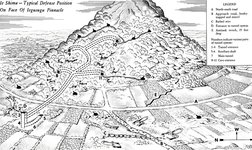

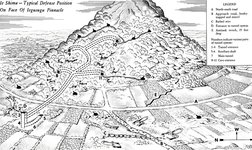

A US military diagram of typical Japanese hill defensive tunnels and installations

A Japanese Type 89 150mm gun hidden inside a cave defensive system

A map of Okinawa's airfields, 1945

Military use of children[]

On Okinawa, the Imperial Japanese Army mobilized 1,780 schoolboys aged 14–17 years into front-line-service as an Iron and Blood Imperial Corps (Tekketsu Kinnōtai ja:鉄血勤皇隊), while Himeyuri students were organized into a nursing unit.[21] This mobilization was conducted by an ordinance of the Ministry of the Army, not by law. The ordinances mobilized the students as volunteer soldiers for form's sake; in reality, the military authorities ordered schools to force almost all students to "volunteer" as soldiers; sometimes they counterfeited the necessary documents. About half of the Tekketsu Kinnōtai were killed, including in suicide bomb attacks against tanks, and in guerrilla operations.

Among the 21 male and female secondary schools that made up these student corps, 2,000 students would die on the battlefield. Even with the female students acting mainly as nurses to Japanese soldiers they would still be exposed to the harsh conditions of war.[25]

[]

There was a hypnotic fascination to the sight so alien to our Western philosophy. We watched each plunging kamikaze with the detached horror of one witnessing a terrible spectacle rather than as the intended victim. We forgot self for the moment as we groped hopelessly for the thought of that other man up there.

The United States Navy's Task Force 58, deployed to the east of Okinawa with a picket group of from 6 to 8 destroyers, kept 13 carriers (7 CVs and 6 CVLs) on duty from 23 March to 27 April and a smaller number thereafter. Until 27 April, a minimum of 14 and up to 18 escort carriers (CVEs) were in the area at all times. Until 20 April, British Task Force 57, with 4 large and 6 escort carriers, remained off the Sakishima Islands to protect the southern flank.[12]:97

The protracted length of the campaign under stressful conditions forced Admiral Chester W. Nimitz to take the unprecedented step of relieving the principal naval commanders to rest and recuperate. Following the practice of changing the fleet designation with the change of commanders, US naval forces began the campaign as the US 5th Fleet under Admiral Raymond Spruance, but ended it as the 3rd Fleet under Admiral William Halsey.

Japanese air opposition had been relatively light during the first few days after the landings. However, on 6 April, the expected air reaction began with an attack by 400 planes from Kyushu. Periodic heavy air attacks continued through April. During the period 26 March – 30 April, twenty American ships were sunk and 157 damaged by enemy action. For their part, by 30 April, the Japanese had lost more than 1,100 planes to Allied naval forces alone.[12]:102

Between 6 April and 22 June, the Japanese flew 1,465 kamikaze aircraft in large-scale attacks from Kyushu, 185 individual kamikaze sorties from Kyushu, and 250 individual kamikaze sorties from Formosa. While US intelligence estimated there were 89 planes on Formosa, the Japanese actually had about 700, dismantled or well camouflaged and dispersed into scattered villages and towns; the US Fifth Air Force disputed Navy claims of kamikaze coming from Formosa.[27][clarification needed]

The ships lost were smaller vessels, particularly the destroyers of the radar pickets, as well as destroyer escorts and landing ships. While no major allied warships were lost, several fleet carriers were severely damaged. Land-based Shin'yō-class suicide motorboats were also used in the Japanese suicide attacks, although Ushijima had disbanded the majority of the suicide boat battalions before the battle due to expected low effectiveness against a superior enemy. The boat crews were re-formed into three additional infantry battalions.[28]

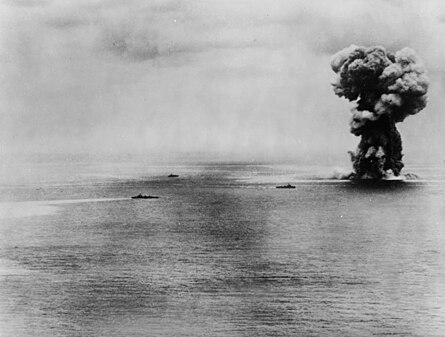

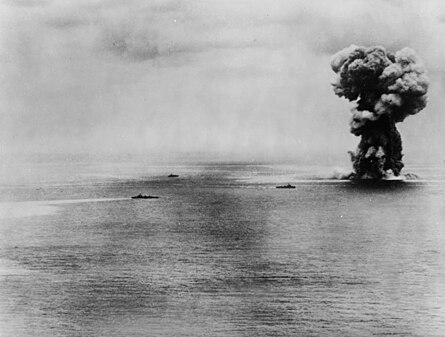

The super battleship Yamato explodes after persistent attacks from US aircraft.

American aircraft carrier USS Bunker Hill burns after being hit by two kamikaze planes within 30 seconds.

Operation Ten-Go[]

Operation Ten-Go (Ten-gō sakusen) was the attempted attack by a strike force of 10 Japanese surface vessels, led by Yamato and commanded by Admiral Seiichi Itō. This small task force had been ordered to fight through enemy naval forces, then beach Yamato and fight from shore, using her guns as coastal artillery and her crew as naval infantry. The Ten-Go force was spotted by submarines shortly after it left the Japanese home waters, and was intercepted by US carrier aircraft.

Under attack from more than 300 aircraft over a two-hour span, the world's largest battleship sank on 7 April 1945, after a one-sided battle, long before she could reach Okinawa. (US torpedo bombers were instructed to aim for only one side to prevent effective counter flooding by the battleship's crew, and to aim for the bow or the stern, where armor was believed to be the thinnest.) Of Yamato's screening force, the light cruiser Yahagi and 4 of the 8 destroyers were also sunk. The Imperial Japanese Navy lost some 3,700 sailors, including Admiral Itō, at the cost of 10 US aircraft and 12 airmen.

British Pacific Fleet[]

The British Pacific Fleet, taking part as Task Force 57, was assigned the task of neutralizing the Japanese airfields in the Sakishima Islands, which it did successfully from 26 March to 10 April.

On 10 April, its attention was shifted to airfields in northern Formosa. The force withdrew to San Pedro Bay on 23 April.

On 1 May, the British Pacific Fleet returned to action, subduing the airfields as before, this time with naval bombardment as well as aircraft. Several kamikaze attacks caused significant damage, but as the Royal Navy carriers had armoured flight decks, they experienced only a brief interruption to their force's operations.[29][30]

Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm Avengers, Seafires and Fireflies on HMS Implacable warm up their engines before taking off.

HMS Formidable on fire after a kamikaze attack on May 4. The ship was out of action for fifty minutes.

Land battle[]

The land battle took place over about 81 days beginning on 1 April 1945. The first Americans ashore were soldiers of the 77th Infantry Division, who landed in the Kerama Islands, 15 mi (24 km) west of Okinawa on 26 March. Subsidiary landings followed, and the Kerama group was secured over the next five days. In these preliminary operations, the 77th Infantry Division suffered 27 dead and 81 wounded, while the Japanese dead and captured numbered over 650. The operation provided a protected anchorage for the fleet and eliminated the threat from suicide boats.[12]:50–60

On 31 March, Marines of the Amphibious Reconnaissance Battalion landed without opposition on Keise Shima, four islets just 8 mi (13 km) west of the Okinawan capital of Naha. A group of 155 mm (6.1 in) "Long Tom" artillery pieces went ashore on the islets to cover operations on Okinawa.[12]:57

Northern Okinawa[]

The main landing was made by the XXIV Corps and the III Amphibious Corps on the Hagushi beaches on the western coast of Okinawa on L-Day, 1 April. The 2nd Marine Division conducted a demonstration off the Minatoga beaches on the southeastern coast to deceive the Japanese about American intentions and delay movement of reserves from there.[12]:68–74

Tenth Army swept across the south-central part of the island with relative ease, capturing the Kadena and the Yomitan airbases within hours of the landing.[15]:67–9[12]:74–5 In light of the weak opposition, General Buckner decided to proceed immediately with Phase II of his plan, the seizure of northern Okinawa. The 6th Marine Division headed up the and by 7 April, had sealed off the Motobu Peninsula.[12]:138–41

Six days later on 13 April, the 2nd Battalion, 22nd Marine Regiment, reached Hedo Point (Hedo-misaki) at the northernmost tip of the island. By this point, the bulk of the Japanese forces in the north (codenamed Udo Force) were cornered on the Motobu Peninsula. Here, the terrain was mountainous and wooded, with the Japanese defenses concentrated on Yae-Dake, a twisted mass of rocky ridges and ravines on the center of the peninsula. There was heavy fighting before the Marines finally cleared Yae-Dake on 18 April.[12]:141–8 However, this was not the end of ground combat in northern Okinawa. On 24 May, the Japanese mounted Operation Gi-gou: a company of Giretsu Kuteitai commandos were airlifted in a suicide attack on Yomitan. They destroyed 70,000 US gallons (260,000 l) of fuel and nine planes before being killed by the defenders, who lost two men.

Meanwhile, the 77th Infantry Division assaulted Ie Island (Ie Shima), a small island off the western end of the peninsula, on 16 April. In addition to conventional hazards, the 77th Infantry Division encountered kamikaze attacks and even local women armed with spears. There was heavy fighting before the area was declared secured on 21 April, and became another airbase for operations against Japan.[12]:149–83

Southern Okinawa[]

While the 6th Marine Division cleared northern Okinawa, the US Army 96th and 7th Infantry Divisions wheeled south across the narrow waist of Okinawa. The 96th Infantry Division began to encounter fierce resistance in west-central Okinawa from Japanese troops holding fortified positions east of Highway No. 1 and about 5 mi (8 km) northwest of Shuri, from what came to be known as Cactus Ridge.[12]:104–5 The 7th Infantry Division encountered similarly fierce Japanese opposition from a rocky pinnacle located about 1,000 yd (910 m) southwest of Arakachi (later dubbed "The Pinnacle"). By the night of 8 April, American troops had cleared these and several other strongly fortified positions. They suffered over 1,500 battle casualties in the process while killing or capturing about 4,500 Japanese. Yet the battle had only begun, for it was now realized that "these were merely outposts," guarding the Shuri Line.[12]:105–8

The next American objective was (26°15′32″N 127°44′13″E / 26.259°N 127.737°E), two hills with a connecting saddle that formed part of Shuri's outer defenses. The Japanese had prepared their positions well and fought tenaciously. The Japanese soldiers hid in fortified caves. American forces often lost personnel before clearing the Japanese out from each cave or other hiding place. The Japanese sent Okinawans at gunpoint out to obtain water and supplies for them, which led to civilian casualties. The American advance was inexorable but resulted in a high number of casualties on both sides.[12]:110–25

As the American assault against Kakazu Ridge stalled, Lieutenant General Ushijima – influenced by General Chō — decided to take the offensive. On the evening of 12 April, the 32nd Army attacked American positions across the entire front. The Japanese attack was heavy, sustained, and well organized. After fierce close combat, the attackers retreated, only to repeat their offensive the following night. A final assault on 14 April was again repulsed. The effort led the 32nd Army's staff to conclude that the Americans were vulnerable to night infiltration tactics, but that their superior firepower made any offensive Japanese troop concentrations extremely dangerous, and they reverted to their defensive strategy.[12]:130–7

The 27th Infantry Division, which had landed on 9 April, took over on the right, along the west coast of Okinawa. General John R. Hodge now had three divisions in the line, with the 96th in the middle and the 7th to the east, with each division holding a front of only about 1.5 mi (2.4 km). Hodge launched a new offensive on 19 April with a barrage of 324 guns, the largest ever in the Pacific Ocean Theater. Battleships, cruisers, and destroyers joined the bombardment, which was followed by 650 Navy and Marine planes attacking the Japanese positions with napalm, rockets, bombs, and machine guns. The Japanese defenses were sited on reverse slopes, where the defenders waited out the artillery barrage and aerial attack in relative safety, emerging from the caves to rain mortar rounds and grenades upon the Americans advancing up the forward slope.[12]:184–94

A tank assault to achieve breakthrough by outflanking Kakazu Ridge failed to link up with its infantry support attempting to cross the ridge and therefore failed with the loss of 22 tanks. Although flame tanks cleared many cave defenses, there was no breakthrough, and the XXIV Corps suffered 720 casualties. The losses might have been greater except for the fact that the Japanese had practically all of their infantry reserves tied up farther south, held there by another feint off the Minatoga beaches by the 2nd Marine Division that coincided with the attack.[12]:196–207

At the end of April, after Army forces had pushed through the Machinato defensive line,[31] the 1st Marine Division relieved the 27th Infantry Division and the 77th Infantry Division relieved the 96th. When the 6th Marine Division arrived, the III Amphibious Corps took over the right flank and Tenth Army assumed control of the battle.[12]:265

On 4 May, the 32nd Army launched another counteroffensive. This time, Ushijima attempted to make amphibious assaults on the coasts behind American lines. To support his offensive, the Japanese artillery moved into the open. By doing so, they were able to fire 13,000 rounds in support, but effective American counter-battery fire destroyed dozens of Japanese artillery pieces. The attack failed.[12]:283–302

Buckner launched another American attack on 11 May. Ten days of fierce fighting followed. On 13 May, troops of the 96th Infantry Division and 763rd Tank Battalion captured Conical Hill (26°12′47″N 127°45′00″E / 26.213°N 127.75°E). Rising 476 ft (145 m) above the Yonabaru coastal plain, this feature was the eastern anchor of the main Japanese defenses and was defended by about 1,000 Japanese. Meanwhile, on the opposite coast, the 1st and 6th Marine Divisions fought for "Sugar Loaf Hill" (26°13′19″N 127°41′46″E / 26.222°N 127.696°E). The capture of these two key positions exposed the Japanese around Shuri on both sides. Buckner hoped to envelop Shuri and trap the main Japanese defending force.[12]:311–59

By the end of May, monsoon rains which had turned contested hills and roads into a morass exacerbated both the tactical and medical situations. The ground advance began to resemble a World War I battlefield, as troops became mired in mud, and flooded roads greatly inhibited evacuation of wounded to the rear. Troops lived on a field sodden by rain, part garbage dump and part graveyard. Unburied Japanese and American bodies decayed, sank in the mud and became part of a noxious stew. Anyone sliding down the greasy slopes could easily find their pockets full of maggots at the end of the journey.[32][12]:364–70

From 24 to 27 May the 6th Marine Division cautiously occupied the ruins of Naha, the largest city on the island, finding it largely deserted.[12]:372–7

On 26 May aerial observers saw large troop movements just below Shuri. On 28 May Marine patrols found recently abandoned positions west of Shuri. By 30 May the consensus among Army and Marine intelligence was that the majority of Japanese forces had withdrawn from the Shuri Line.[12]:391–2 On 29 May the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines occupied high ground 700 yards (640 m) east of Shuri Castle and reported that the Castle appeared undefended. At 10:15 Company A, 1/5 Marines occupied the Castle[12]:395–6

Shuri Castle had been shelled by the battleship USS Mississippi for three days before this advance.[33] Due to this, the 32nd Army withdrew to the south and thus the Marines had an easy task of securing Shuri Castle.[33][34] The castle, however, was outside the 1st Marine Division's assigned zone and only frantic efforts by the commander and staff of the 77th Infantry Division prevented an American airstrike and artillery bombardment which would have resulted in many casualties due to friendly fire.[12]:396

The Japanese retreat, although harassed by artillery fire, was conducted with great skill at night and aided by the monsoon storms. The 32nd Army was able to move nearly 30,000 personnel into its last defense line on the Kiyan Peninsula, which ultimately led to the greatest slaughter on Okinawa in the latter stages of the battle, including the deaths of thousands of civilians. In addition, there were 9,000 IJN troops supported by 1,100 militia, with approximately 4,000 holed up at the underground headquarters on the hillside overlooking the Okinawa Naval Base in the Oroku Peninsula, east of the airfield.[12]:392–4

On 4 June, elements of the 6th Marine Division launched an amphibious assault on the peninsula. The 4,000 Japanese sailors, including Admiral Ōta, all committed suicide within the hand-built tunnels of the underground naval headquarters on 13 June.[12]:427–34

By 17 June, the remnants of Ushijima's shattered 32nd Army were pushed into a small pocket in the far south of the island to the southeast of Itoman.[12]:455–61

On 18 June, General Buckner was killed by Japanese artillery fire while monitoring the progress of his troops from a forward observation post. Buckner was replaced by Major general Roy Geiger. Upon assuming command, Geiger became the only US Marine to command a numbered army of the US Army in combat; he was relieved five days later by General Joseph Stilwell. On 19 June, General Claudius Miller Easley, the commander of the 96th Infantry Division, was killed by Japanese machine-gun fire, also while checking on the progress of his troops at the front.[12]:461

The last remnants of Japanese resistance ended on 21 June, although some Japanese continued hiding, including the future governor of Okinawa Prefecture, Masahide Ōta.[35] Ushijima and Chō committed suicide by seppuku in their command headquarters on Hill 89 in the closing hours of the battle.[12]:468–71 Colonel Yahara had asked Ushijima for permission to commit suicide, but the general refused his request, saying: "If you die there will be no one left who knows the truth about the battle of Okinawa. Bear the temporary shame but endure it. This is an order from your army Commander."[26]:723 Yahara was the most senior officer to have survived the battle on the island, and he later authored a book titled The Battle for Okinawa. On 22 June Tenth Army held a flag-arising ceremony to mark the end of organized resistance on Okinawa. On 23 June a mopping-up operation commenced, which concluded on 30 June.[12]:471–3

On 15 August 1945, Admiral Matome Ugaki was killed while part of a kamikaze raid on Iheyajima island. The official surrender ceremony was held on 7 September, near the Kadena airfield.

Casualties[]

Okinawa was the bloodiest battle of the Pacific War.[36][37] The most complete tally of deaths during the battle is at the Cornerstone of Peace monument at the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum, which identifies the names of each individual who died at Okinawa in World War II. As of 2010, the monument lists 240,931 names, including 149,193 Okinawan civilians, 77,166 Imperial Japanese soldiers, 14,009 American soldiers, and smaller numbers of people from South Korea (365), the United Kingdom (82), North Korea (82) and Taiwan (34).[6]

The numbers correspond to recorded deaths during the Battle of Okinawa from the time of the American landings in the Kerama Islands on 26 March 1945, to the signing of the Japanese surrender on 2 September 1945, in addition to all Okinawan casualties in the Pacific War in the 15 years from the Manchurian Incident, along with those who died in Okinawa from war-related events in the year before the battle and the year after the surrender.[38] 234,183 names were inscribed by the time of unveiling and new names are added each year.[39][40][41] 40,000 of the Okinawan civilians killed had been drafted or impressed by the Japanese army and are often counted as combat deaths.

Military losses[]

American[]

The Americans suffered over 75,000 – 82,000 casualties, including non-battle casualties (psychiatric, injuries, illnesses), of whom over 20,195 were dead (12,500 were killed in action, 7,700 died of wounds or non-combat deaths). Killed in action were 4,907 Navy, 4,675 Army, and 2,938 Marine Corps personnel.[9] The several thousand personnel who died indirectly (from wounds and other causes) at a later date are not included in the total.

The most famous American casualty was Lieutenant General Buckner, whose decision to attack the Japanese defenses head-on, although extremely costly in American lives, was ultimately successful. Four days from the closing of the campaign, Buckner was killed by Japanese artillery fire, which blew lethal slivers of coral into his body, while inspecting his troops at the front line. He was the highest-ranking US officer to be killed by enemy fire during the Second World War. The day after Buckner was killed, Brigadier General Easley was killed by Japanese machine gunfire. The famous war correspondent Ernie Pyle was also killed by Japanese machine-gun fire on Ie Shima, a small island just off of northwestern Okinawa.[42]

Aircraft losses over the three-month period were 768 US planes, including those bombing the Kyushu airfields launching kamikazes. Combat losses were 458, and the other 310 were operational accidents. At sea, 368 Allied ships—including 120 amphibious craft—were damaged while another 36—including 15 amphibious ships and 12 destroyers—were sunk during the Okinawa campaign. The US Navy's dead exceeded its wounded, with 4,907 killed and 4,874 wounded, primarily from kamikaze attacks.[43]

American personnel casualties included thousands of cases of mental breakdown. According to the account of the battle presented in Marine Corps Gazette:

More mental health issues arose from the Battle of Okinawa than any other battle in the Pacific during World War II. The constant bombardment from artillery and mortars coupled with the high casualty rates led to a great deal of personnel coming down with combat fatigue. Additionally, the rains caused mud that prevented tanks from moving and tracks from pulling out the dead, forcing Marines (who pride themselves on burying their dead in a proper and honorable manner) to leave their comrades where they lay. This, coupled with thousands of bodies both friend and foe littering the entire island, created a scent you could nearly taste. Morale was dangerously low by May and the state of discipline on a moral basis had a new low barometer for acceptable behavior. The ruthless atrocities by the Japanese throughout the war had already brought on an altered behavior (deemed so by traditional standards) by many Americans resulting in the desecration of Japanese remains, but the Japanese tactic of using the Okinawan people as human shields brought about a new aspect of terror and torment to the psychological capacity of the Americans.[13]

Medal of Honor recipients from Okinawa are:

- Beauford T. Anderson – 13 April

- Richard E. Bush – 16 April

- Robert Eugene Bush – 2 May

- Henry A. Courtney Jr. – 14–15 May

- Clarence B. Craft – 31 May

- James L. Day – 14–17 May

- Desmond Doss – 29 April – 21 May

- John P. Fardy – 7 May

- William A. Foster – 2 May

- Harold Gonsalves – 15 April

- William D. Halyburton Jr. – 10 May

- Dale M. Hansen – 7 May

- Louis J. Hauge Jr. – 14 May

- Elbert L. Kinser – 4 May

- Fred F. Lester – 8 June

- Martin O. May – 19–21 April

- Richard M. McCool Jr. – 10–11 June

- Robert M. McTureous Jr. – 7 June

- John W. Meagher – 19 June

- Edward J. Moskala – 9 April

- Joseph E. Muller – 15–16 May

- Alejandro R. Ruiz – 28 April

- Albert E. Schwab – 7 May

- Seymour W. Terry – 11 May

[]

The following table lists the Allied naval vessels that received damage or were sunk in the Battle of Okinawa between 19 March – 30 July, 1945. The table lists a total of 147 damaged ships, five of which were damaged by enemy suicide boats, and another five by mines. One source estimated that total Japanese sorties during the entire Okinawa campaign exceeded 3,700, with a large percentage kamikaze, and that the attackers damaged slightly more than 200 Allied vessels, with 4900 naval officers and seamen killed and roughly 4,824 wounded or missing.[44][45] The USS Thorton is not listed as it was damaged as the result of a collision with another US ship. Those ships in a pink background, and with an asterisk were sunk or had to be scuttled due to irreparable damage. Of those sunk, the majority were relatively smaller ships; these included destroyers of around 300–450 feet. A few small cargo ships were also sunk, several containing munitions which caught fire. Those ships whose names are preceded by a "#" pound sign, were scrapped or decommissioned as a result of damage

Japanese losses[]

The US military estimates that 110,071 Japanese soldiers were killed during the battle. This total includes conscripted Okinawan civilians.

A total of 7,401 Japanese regulars and 3,400 Okinawan conscripts surrendered or were captured during the battle. Additional Japanese and renegade Okinawans were captured or surrendered over the next few months, bringing the total to 16,346.[12]:489 This was the first battle in the Pacific War in which thousands of Japanese soldiers surrendered or were captured. Many of the prisoners were native Okinawans who had been pressed into service shortly before the battle and were less imbued with the Imperial Japanese Army's no-surrender doctrine.[21] When the American forces occupied the island, many Japanese soldiers put on Okinawan clothing to avoid capture, and some Okinawans would come to the Americans' aid by offering to identify these mainland Japanese.

The Japanese lost 16 combat vessels, including the super battleship Yamato. Early claims of Japanese aircraft losses put the total at 7,800,[12]:474 however later examination of Japanese records revealed that Japanese aircraft losses at Okinawa were far below often-repeated US estimates for the campaign.[14] The number of conventional and kamikaze aircraft actually lost or expended by the 3rd, 5th, and 10th Air Fleets, combined with about 500 lost or expended by the Imperial Army at Okinawa, was roughly 1,430.[14] The Allies destroyed 27 Japanese tanks and 743 artillery pieces (including mortars, anti-tank and anti-aircraft guns), some of them eliminated by the naval and air bombardments but most knocked out by American counter-battery fire.

Civilian losses, suicides, and atrocities[]

Some of the other islands that saw major battles in World War II, such as Iwo Jima, were uninhabited or had been evacuated. Okinawa, by contrast, had a large indigenous civilian population; US Army records from the planning phase of the operation make the assumption that Okinawa was home to about 300,000 civilians. According to various estimates, between a tenth and a third of them died during the battle,[32] or between 30,000 and 100,000 people. The official US Tenth Army count for the 82-day campaign is a total of 142,058 recovered enemy bodies (including those civilians pressed into service by the Imperial Japanese Army), with the deduction made that about 42,000 were non-uniformed civilians who had been killed in the crossfire. Okinawa Prefecture's estimate is over 100,000 losses,[63]

During the battle, American forces found it difficult to distinguish civilians from soldiers. It became common for them to shoot at Okinawan houses, as one infantryman wrote:

There was some return fire from a few of the houses, but the others were probably occupied by civilians – and we didn't care. It was a terrible thing not to distinguish between the enemy and women and children. Americans always had great compassion, especially for children. Now we fired indiscriminately.[64]

In its history of the war, the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum[63] presents Okinawa as being caught between Japan and the United States. During the 1945 battle, the Imperial Japanese Army showed indifference to Okinawans' safety, and its soldiers even used civilians as human shields or just outright murdered them. The Japanese military also confiscated food from the Okinawans and executed those who hid it, leading to mass starvation, and forced civilians out of their shelters. Japanese soldiers also killed about 1,000 people who spoke in the Okinawan language to suppress spying.[65] The museum writes that "some were blown apart by [artillery] shells, some finding themselves in a hopeless situation were driven to suicide, some died of starvation, some succumbed to malaria, while others fell victim to the retreating Japanese troops."[63]

With the impending Japanese defeat, civilians often committed mass suicide, urged on by the Japanese soldiers who told locals that victorious American soldiers would go on a rampage of killing and raping. Ryūkyū Shimpō, one of the two major Okinawan newspapers, wrote in 2007: "There are many Okinawans who have testified that the Japanese Army directed them to commit suicide. There are also people who have testified that they were handed grenades by Japanese soldiers" to blow themselves up.[66] Thousands of civilians, having been induced by Japanese propaganda to believe that American soldiers were barbarians who committed horrible atrocities, killed their families and themselves to avoid capture at the hands of the Americans. Some of them threw themselves and their family members from the southern cliffs where the Peace Museum now resides.[67] Okinawans "were often surprised at the comparatively humane treatment they received from the American enemy".[68][69] Islands of Discontent: Okinawan Responses to Japanese and American Power by Mark Selden alleges that the Americans "did not pursue a policy of torture, rape, and murder of civilians as Japanese military officials had warned".[70] American Military Intelligence Corps[71] combat translators such as Teruto Tsubota managed to convince many civilians not to kill themselves.[72] Survivors of the mass suicides blamed also the indoctrination of their education system of the time, in which the Okinawans were taught to become "more Japanese than the Japanese", and were expected to prove it.[73]

Witnesses and historians claim that soldiers, mainly Japanese troops, raped Okinawan women during the battle. Rape by Japanese troops reportedly "became common"[attribution needed] in June, after it became clear that the Imperial Japanese Army had been defeated.[21][12]:462 Marine Corps officials in Okinawa and Washington have said that they knew of no rapes by American personnel in Okinawa at the end of the war.[74] There are, however, numerous credible testimony accounts which note that a large number of rapes were committed by American forces during the battle. This includes stories of rape after trading sexual favors or even marrying Americans,[75] such as the alleged incident in the village of Katsuyama, where civilians said they had formed a vigilante group to ambush and kill three black American soldiers who they claimed would frequently rape the local girls there.[76]

MEXT textbook controversy[]

There is ongoing disagreement between Okinawa's local government and Japan's national government over the role of the Japanese military in civilian mass suicides during the battle. In March 2007, the national Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) advised textbook publishers to reword descriptions that the embattled Imperial Japanese Army forced civilians to kill themselves in the war to avoid being taken prisoner. MEXT preferred descriptions that just say that civilians received hand grenades from the Japanese military. This move sparked widespread protests among Okinawans. In June 2007, the Okinawa Prefectural Assembly adopted a resolution stating, "We strongly call on the (national) government to retract the instruction and to immediately restore the description in the textbooks so the truth of the Battle of Okinawa will be handed down correctly and a tragic war will never happen again."[77][78]

On 29 September 2007, about 110,000 people held the biggest political rally in the history of Okinawa to demand that MEXT retract its order to textbook publishers regarding revising the account of the civilian suicides. The resolution stated, "It is an undeniable fact that the 'multiple suicides' would not have occurred without the involvement of the Japanese military and any deletion of or revision to (the descriptions) is a denial and distortion of the many testimonies by those people who survived the incidents."[79] In December 2007, MEXT partially admitted the role of the Japanese military in civilian mass suicides.[80] The ministry's Textbook Authorization Council allowed the publishers to reinstate the reference that civilians "were forced into mass suicides by the Japanese military", on condition it is placed in sufficient context. The council report stated, "It can be said that from the viewpoint of the Okinawa residents, they were forced into the mass suicides."[81] That was not enough for the survivors who said it is important for children today to know what really happened.[82]

The Nobel Prize-winning author Kenzaburō Ōe wrote a booklet that states that the mass suicide order was given by the military during the battle.[83] He was sued by revisionists, including a wartime commander during the battle, who disputed this and wanted to stop publication of the booklet. At a court hearing, Ōe testified "Mass suicides were forced on Okinawa islanders under Japan's hierarchical social structure that ran through the state of Japan, the Japanese armed forces and local garrisons."[84] In March 2008, the Osaka Prefecture Court ruled in favor of Ōe, stating, "It can be said the military was deeply involved in the mass suicides." The court recognized the military's involvement in the mass suicides and murder-suicides, citing the testimony about the distribution of grenades for suicide by soldiers and the fact that mass suicides were not recorded on islands where the military was not stationed.[85]

In 2012, Korean-Japanese director Pak Su-nam announced her work on the documentary Nuchigafu (Okinawan for "only if one is alive") collecting living survivors' accounts to show "the truth of history to many people", alleging that "there were two types of orders for 'honorable deaths'—one for residents to kill each other and the other for the military to kill all residents".[86] In March 2013, Japanese textbook publisher Shimizu Shoin was permitted by MEXT to publish the statements that "Orders from Japanese soldiers led to Okinawans committing group suicide" and "The [Japanese] army caused many tragedies in Okinawa, killing local civilians and forcing them to commit mass suicide."[87]

Aftermath[]

90% of the buildings on the island were destroyed, along with countless historical documents, artifacts, and cultural treasures, and the tropical landscape was turned into "a vast field of mud, lead, decay and maggots".[88] The military value of Okinawa "exceeded all hope". Okinawa provided a fleet anchorage, troop staging areas, and airfields in proximity to Japan. The US cleared the surrounding waters of mines in Operation Zebra, occupied Okinawa, and set up the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands, a form of military government, after the battle.[89] In 2011, one official of the prefectural government told David Hearst of The Guardian:

You have the Battle of Britain, in which your airmen protected the British people. We had the Battle of Okinawa, in which the exact opposite happened. The Japanese army not only starved the Okinawans but used them as human shields. That dark history is still present today – and Japan and the US should study it before they decide what to do with next.[90]

Effect on the wider war[]

Because the next major event following the Battle of Okinawa was "the total surrender of Japan," the "effect" of this battle is more difficult to consider. Due to the surrender, the next anticipated series of battles, an invasion of the Japanese homeland, never occurred and all military strategies on both sides which presupposed this apparently-inevitable next development were immediately rendered moot.

Some military historians believe that the Okinawa campaign led directly to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as a means of avoiding the planned ground invasion of the Japanese mainland. This view is explained by Victor Davis Hanson in his book Ripples of Battle:

... because the Japanese on Okinawa ... were so fierce in their defense (even when cut off and without supplies), and because casualties were so appalling, many American strategists looked for an alternative means to subdue mainland Japan, other than a direct invasion. This means presented itself, with the advent of atomic bombs, which worked admirably in convincing the Japanese to sue for peace [unconditionally], without American casualties.

Meanwhile, many parties continue to debate the broader question of "why Japan surrendered", attributing the surrender to a number of possible reasons including: the atomic bombings,[91][92][93] the Soviet invasion of Manchuria,[94][95] and Japan's depleted resources.[96][page needed][97]

Memorial[]

In 1995, the Okinawa government erected a memorial monument named the Cornerstone of Peace in Mabuni, the site of the last fighting in southeastern Okinawa.[98] The memorial lists all the known names of those who died in the battle, civilian and military, Japanese and foreign. As of June 2008, it contains 240,734 names including 382 Koreans.[99]

Modern US base[]

Significant US forces remain garrisoned on Okinawa as the United States Forces Japan, which the Japanese government sees as an important guarantee of regional stability,[100] and Kadena remains the largest US air base in Asia. Local residents have protested against the size and presence of the base.[101][102]

See also[]

- Himeyuri students

- Chiran Special Attack Peace Museum

- History of the Ryukyus

- Josef R. Sheetz

- Rape during the occupation of Japan

- Suicide in Japan

- Okinawa Memorial Day

- Marine Corps Air Station Futenma

- Camp Hansen

- Torii Station

- Camp Schwab

- Camp Foster

- Camp Kinser

- Giretsu Kuteitai

- Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum

References[]

Citations[]

- ^ "Ryukus". US Army Center of Military History.

- ^ 26 March marked the first landing on the Kerama Islands around Okinawa in the Ryukus by the 77th Division.

- ^ Sloan 2007, p. 18

- ^ Jump up to: a b Keegan, John (2005). The Second World War. Penguin. ISBN 9780143195085.

- ^ Hastings 2007, p. 370

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Number of names Inscribed/沖縄県". Okinawa Prefecture. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Keegan, John (1989). The Times Atlas of the Second World War. Times Books. p. 169. ISBN 9780723003175.

- ^ Jump up to: a b The National Archives: Heroes and Villains. Retrieved 22 July 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Frank 1999, p. 71.

- ^ "The Second World Wars: How the First Global Conflict Was Fought and Won" p. 302

- ^ "HyperWar: US Army in WWII: Okinawa: The Last Battle". ibiblio.org.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Appleman, Roy; Burns, James; Gugeler, Russel; Stevens, John (1948). Okinawa: The Last Battle. United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 1-4102-2206-3.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e SSgt Rudy R. Frame, Jr. "Okinawa: The Final Great Battle of World War II | Marine Corps Gazette". Mca-marines.org. Archived from the original on 14 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Giangreco, D. (2009). Hell to Pay Operation Downfall and the Invasion of Japan, 1945–47. Naval Institute Press. p. 91. ISBN 9781591143161.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nichols, Charles; Shaw, Henry (1955). Okinawa: Victory in the Pacific (PDF). Government Printing Office. ASIN B00071UAT8.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Feifer 2001 pages 99–106

- ^ "The United States Navy assembled an unprecedented armada in March and April 1945". Militaryhistoryonline.com. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ "The American invasion of Okinawa was the largest amphibious invasion of all time". Historynet.com. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ "Okinawa: The Typhoon of Steel". American Veterans Center. 1 April 1945. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ At 60th anniversary, Battle of Okinawa survivors recall 'Typhoon of Steel' – News – Stripes, Allen, David; Stars and Stripes; 1 April 2005.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Huber, Thomas (May 1990). "Japan's battle of Okinawa, April–June 1945". Combined Arms Research Library. Archived from the original on 16 October 2004.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Rottman, Gordon (2002). Okinawa 1945: The Last Battle. Osprey Publishing. p. 39. ISBN 1-84176-546-5.

- ^ The Great Courses. World War II: The Pacific Theater. Lecture 21. Professor Craig Symonds

- ^ Hobbs, David (January 2013). "The Royal Navy's Pacific Strike Force". US Naval Institute. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- ^ "[OFFICIAL] HIMEYURI PEACE MUSEUM".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Toland, John (1970). The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire 1936–1945. Random House. ISBN 9780804180955.

- ^ Baldwin, Hanson W. Sea Fights and Shipwrecks Hanover House 1956 page 309

- ^ Christopher Chant, "The Encyclopedia of Codenames of World War II (Routledge Revivals)", p. 87

- ^ Hastings 2007, p. 401

- ^ Hobbs 2012, pp. 175–76

- ^ West Point Atlas of American Wars

- ^ Jump up to: a b Battle of Okinawa, GlobalSecurity.org.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "The Ordeals of Shuri Castle". Wonder-okinawa.jp. 15 August 1945. Archived from the original on 4 July 2009. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ "The Final Campaign: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa (Assault on Shuri)". Nps.gov. Archived from the original on 15 April 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ ""The World is beginning to know Okinawa": Ota Masahide reflects on his life from the Battle of Okinawa to the Struggle for Okinawa". Japanfocus.org. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ "Battle of Okinawa: The Bloodiest Battle of the Pacific War". HistoryNet. 12 June 2006. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ Manchester, William (14 June 1987). "The Bloodiest Battle Of All". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ^ "The Cornerstone of Peace – names to be inscribed". Okinawa Prefecture. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ Weiner, Michael (ed.) (1997). Japan's minorities: the illusion of homogeneity (pp.169f.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13008-5.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ "Recollecting the War in Okinawa". Japan Policy Research Institute. Retrieved 4 February 2011.

- ^ "Okinawa marks 62nd anniversary of WWII battle". Japan Times. 24 June 2007. Retrieved 14 September 2007.

- ^ Reid, Chip. "Ernie Pyle, trail-blazing war correspondent—Brought home the tragedy of D-Day and the rest of WWII", NBC News, 7 June 2004. Retrieved 26 April 2006.

- ^ "The Amphibians Came to Conquer". Ibiblio.org. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Toll, Ian, Twilight of the Gods, (2020) Norton and Co., New York, New York, pg. 593

- ^ "The British Fleet at Okinawa". The British Fleet at Okinawa. WWII Forums. Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ All information is public domain from United States Navy, with casualties taken from individual action reports, table format and structure is heavily borrowed from Morison, Samuel, Eliot, Victory in the Pacific, 1945, (Copyright 1960), Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland, Appendix II pgs. 390-92

- ^ Morison, Victory, pg. 115-16

- ^ Morison, Victory, pg. 176

- ^ Morison, Victory, pg. 177

- ^ Morison, Victory, pg. 177

- ^ Morison, Victory, pg. 218

- ^ Jump up to: a b Morison, Victory, pg. 186-191

- ^ "Destroyer History, USS Howorth". Destroyer History. Destroyer History Foundation.

- ^ Morison, Victory, pg. 192

- ^ Morison, Victory, pg. 184

- ^ "Loss report of PGM-18". www.fold3.com. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "Loss report of YMS-103". www.fold3.com. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ Toll, Ian, Twilight, pg. 597

- ^ Morison, Victory, pg. 147

- ^ "Daily Event for May 24, 2008, William B. Allison". Maritime Quest Article on William B. Allison. Maritime Quest. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Morison, Victory, pg. 275

- ^ Jump up to: a b Morrison, Victory, pg. 279

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The Basic Concept of the Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum". Peace-museum.pref.okinawa.jp. 1 April 2000. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Feifer 2001 page 374

- ^ James Brooke. "1945 suicide order still a trauma on Okinawa". Archived from the original on 14 January 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (1 April 2007). "Japan's Textbooks Reflect Revised History". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- ^ "EDITORIAL – Cornerstone of Peace: A Legacy of Bloodshed". San Francisco Chronicle. 24 June 1995. Retrieved 10 December 2013.

- ^ Molasky, Michael S. (1999). The American Occupation of Japan and Okinawa: Literature and Memory. Routledge. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-415-19194-4.

- ^ Molasky, Michael S.; Rabson, Steve (2000). Southern Exposure: Modern Japanese Literature from Okinawa. University of Hawaii Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8248-2300-9.

- ^ Sheehan, Susan D; Elizabeth, Laura; Selden, Hein Mark. "Islands of Discontent: Okinawan Responses to Japanese and American Power": 18. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - ^ "Military Intelligence Service Research Center: Okinawa". Njahs.org. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Defiant soldier saved lives of hundreds of civilians during Okinawa battle, Stars and Stripes, 1 April 2005.

- ^ Toru Saito. "Pressure to prove loyalty paved way for mass suicides in Battle of Okinawa – AJW by The Asahi Shimbun". Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Sims, Calvin (1 June 2000). "3 Dead Marines and a Secret of Wartime Okinawa". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ Tanaka, Yuki (2003). Japan's Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery and Prostitution During World War II. Routledge. ISBN 0-203-30275-3.

- ^ Lisa Takeuchi Cullen (13 August 2001). "Okinawa Nights". Time. Archived from the original on 10 March 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- ^ Okinawa slams history text rewrite, Japan Times, 23 June 2007.

- ^ Gheddo, Piero. "JAPAN Okinawa against Tokyo's attempts to rewrite history – Asia News". Asianews.it. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ "110,000 protest history text revision order". Search.japantimes.co.jp. 30 September 2007. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Japan to amend textbook accounts of Okinawa suicides Herald Tribune, 26 December 2007.

- ^ Texts reinstate army's role in mass suicides: Okinawa prevails in history row Japan Times, 27 December 2007.

- ^ Okinawa's war time wounds reopened BBC News, 17 November 2007.

- ^ Witness: Military ordered mass suicides, Japan Times, 12 September 2007.

- ^ Oe testifies military behind Okinawa mass suicides Archived 12 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Japan Times, 10 November 2007.

- ^ Court sides with Oe over mass suicides, Japan Times, 29 March 2008.

- ^ Nayoki Himeno, Director humanizes tragedy of Okinawan mass suicides Archived 28 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine, The Asashi Shimbun, 24 May 2012.

- ^ New high school texts say Japanese Imperial Army ordered WWII Okinawa suicides, The Mainichi, 29 March 2013.

- ^ "Okinawan History and Karate-do". Archived from the original on 19 August 2011.

- ^ Fisch, Arnold G. (December 2004). Military Government in the Ryukyu Islands, 1945–1950. ISBN 1410218791.

- ^ David Hearst in Okinawa. "Second battle of Okinawa looms as China's naval ambition grows". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Maddox, Robert James (2004). Weapons for Victory: The Hiroshima Decision. University of Missouri Press. p. xvii. ISBN 978-0-826-21562-8.

- ^ Frank 1999, p. 331.

- ^ Gaddis, John Lewis (2005). The Cold War. Allen Lane. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-713-99912-9.

[Hiroshima and Nagasaki] brought about the Japanese surrender.

- ^ "Soviets declare war on Japan; invade Manchuria". History.com. A&E Television Networks, n.d. Web. 6 July 2014.

- ^ "Did Nuclear Weapons Cause Japan to Surrender?". Wilson, Ward. YouTube. Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, 16 January 2013. Web. 6 July 2014.

- ^ Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi (2005). Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674022416.

- ^ "Why did Japan surrender?". Boston Globe. 7 August 2011.

- ^ "The Cornerstone of Peace" (in Japanese). Pref.okinawa.jp. Archived from the original on 6 June 2012. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- ^ Okinawa is promised reduced base burden, Japan Times, 24 June 2008

- ^ "Press rewind: Trump, Tokyo and a welcome back to the 1980s". BBC News. 9 February 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2017.

- ^ "Okinawa marks 68th anniversary of bloody WWII battle". Fox News Channel. 23 June 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- ^ Fackler, Martin (5 July 2013). "In Okinawa, Talk of Break From Japan Turns Serious". The New York Times.

Sources[]

- Primary sources

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Army Center of Military History.

- Alexander, Joseph (1995). The Final Campaign: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa (PDF). U.S. Marine Corps History Division.

- Appleman, Roy; Burns, James; Gugeler, Russel; Stevens, John (1948). Okinawa: The Last Battle. United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 1-4102-2206-3.

- Fisch Jr., Arnold G. (2004). Ryukyus. World War II Campaign Brochures. Washington, DC: United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 0-16-048032-9. CMH Pub 72-35.

- Hobbs, David (2012). The British Pacific Fleet: The Royal Navy's Most Powerful Strike Force. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 9781783469222.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (2002). Victory in the Pacific, 1945, vol. 14 of History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-07065-8.

- Nash, Douglas (2015). Battle of Okinawa III MEF Staff Ride Battle Book (PDF). U.S. Marine Corps History Division.

- Nichols, Charles; Shaw, Henry (1955). Okinawa: Victory in the Pacific (PDF). Government Printing Office. ASIN B00071UAT8.

- Secondary sources

- Astor, Gerald (1996). Operation Iceberg: The Invasion and Conquest of Okinawa in World War II. Dell. ISBN 0-440-22178-1.

- Buckner, Simon; Stilwell, Joseph (2004). Nicholas Evan Sarantakes (ed.). Seven Stars: The Okinawa Battle Diaries of Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr. and Joseph Stilwell.

- Feifer, George (2001). The Battle of Okinawa: The Blood and the Bomb. The Lyons Press. ISBN 1-58574-215-5.

- Frank, Richard B. (1999). Downfall: The End of the Imperial Japanese Empire. Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-41424-7.

- Hallas, James H. (2006). Killing Ground on Okinawa: The Battle for Sugar Loaf Hill. Potomac Books. ISBN 1-59797-063-8.

- Hastings, Max (2007). Retribution – The Battle for Japan, 1944–45. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-26351-3.

- Lacey, Laura Homan (2005). Stay Off The Skyline: The Sixth Marine Division on Okinawa—An Oral History. Potomac Books. ISBN 1-57488-952-4.

- Manchester, William (1980). Goodbye, Darkness: A Memoir of the Pacific War. Boston, Toronto: Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 0-316-54501-5.

- Rottman, Gordon (2002). Okinawa 1945: The last Battle. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-546-5.

- Sledge, E. B.; Fussell, Paul (1990). With the Old Breed: At Peleliu and Okinawa. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506714-2., famous Marine memoir

- Sloan, Bill (2007). The Ultimate Battle: Okinawa 1945—The Last Epic Struggle of World War II. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-9246-7.

- Toll, Ian W. (2020). Twilight of the Gods: War in the Western Pacific, 1944–1945. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Yahara, Hiromichi (2001). The Battle for Okinawa. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-18080-7. - Firsthand account of the battle by a surviving Japanese officer.

- Zaloga, Steven (2007). Japanese Tanks 1939–45. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-091-8.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Okinawa. |

- Dyer, George Carroll (1956). "The Amphibians Came to Conquer: The Story of Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner". United States Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on 21 May 2011. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- Huber, Thomas M. (May 1990). "Japan's Battle of Okinawa, April–June 1945". Leavenworth Papers. United States Army Command and General Staff College. Archived from the original on 16 December 2006. Retrieved 20 November 2006.

- A film clip "footage from the National Archives.By Sgt. Rhodes" is available at the Internet Archive

- A film clip "Landings On Okinawa, 1945/04/09 (1945)" is available at the Internet Archive

- A film clip "Argentine Admitted To World Parley, 1945/05/03 (1945)" is available at the Internet Archive

- A film clip "Final Days of Struggle in Okinawa, 1945/07/05 (1945)" is available at the Internet Archive

- US military on the Battle of Okinawa

- New Zealand account with reference to Operation Iceberg

- Cornerstone of Peace

- Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum

- The Peace Learning Archive in OKINAWA

- A photographic record of aircraft carrier HMS Indomitable, 1944–45, including Operation Iceberg, the attack on the Sakashimas

- WWII: Battle of Okinawa Archived 10 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine – slideshow by Life magazine

- Operation Iceberg Operational Documents Archived 26 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine Combined Arms Research Library, Fort Leavenworth, KS

- Oral history interview with Mike Busha, a member of the 6th Marine Division during the Battle of Okinawa Archived 14 December 2012 at archive.today from the Veterans History Project at Central Connecticut State University

- Oral history interview with Albert D'Amico, a Navy Veteran who was aboard LST 278 during the landing at Okinawa Archived 12 December 2012 at archive.today from the Veterans History Project at Central Connecticut State University

- Booknotes interview with Robert Leckie on Okinawa: The Last Battle of World War II, September 3, 1995.

- Battle of Okinawa

- 1945 in Japan

- Battles of World War II involving New Zealand

- Battles of World War II involving Australia

- Naval battles of World War II involving Canada

- Battles of World War II involving Japan

- Battles of World War II involving the United States

- History of Okinawa Prefecture

- Japan campaign

- Murder–suicides in Asia

- United States Armed Forces in Okinawa Prefecture

- United States Marine Corps in World War II

- World War II invasions

- World War II operations and battles of the Pacific theatre

- Invasions of Japan

- Invasions by the United States

- Invasions by the United Kingdom

- Naval battles and operations of World War II involving the United Kingdom

- Amphibious operations of World War II

- April 1945 events

- May 1945 events

- June 1945 events

- Amphibious operations involving the United States

- Japan–United Kingdom military relations

- Itoman, Okinawa