Battle of Raymond

| Battle of Raymond | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Logan's Division Battling the Confederates Near Fourteen Mile Creek | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| James B. McPherson | John Gregg | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| XVII Corps | Gregg's brigade | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 10,000 to 12,000 | 3,000 to 4,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 442 or 446 | 514 or 515 | ||||||

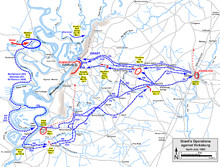

The Battle of Raymond was fought on May 12, 1863, near Raymond, Mississippi, during the Vicksburg Campaign of the American Civil War. After unsuccessful attempts to capture the strategic Mississippi River city of Vicksburg, Major General Ulysses S. Grant of the Union Army led another attempt, beginning in late April 1863. After crossing the river into Mississippi and winning the Battle of Port Gibson, Grant began moving east, with the intention of later turning west and attacking Vicksburg. As part of this movement, Major General James B. McPherson's 10,000 to 12,000-man XVII Corps moved towards Raymond. The Confederate commander of Vicksburg, Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton ordered Brigadier General John Gregg and his 3,000 to 4,000-strong brigade from Jackson to Raymond.

Gregg's brigade made contact with the leading elements of McPherson's corps on May 12. Neither commander was aware of the strength of his opponent, and Gregg acted aggressively, thinking McPherson's force was small enough his men could easily defeat it. McPherson, in turn, overestimated Confederate strength and responded cautiously. The early portions of the battle pitted two brigades of Major General John A. Logan's division against the Confederate force, and the battle was matched relatively evenly. Eventually, McPherson brought up Brigadier General John D. Stevenson's brigade and Brigadier General Marcellus M. Crocker's division. The weight of superior Union numbers eventually began to crack the Confederate line, and Gregg decided to disengage. McPherson's men did not immediately pursue.

The battle at Raymond changed Grant's plans for the Vicksburg campaign, leading him to first focus on neutralizing the Confederate forces at Jackson before turning against Vicksburg. After successfully capturing Jackson, Grant's men then pivoted west, drove Pemberton's force into the defenses of Vicksburg, and forced a Confederate surrender on July 4, ending the Siege of Vicksburg. The site of the battle was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 and public interpretation of a portion of the site is provided by the Friends of Raymond. Modern historians have criticized McPherson's handling of the battle.

Background[]

During the beginning of the American Civil War, Union military leadership developed the Anaconda Plan, a strategy for defeating the Confederate States of America that placed great importance on controlling the Mississippi River.[1] Much of the Mississippi Valley fell under Union control in early 1862 after the capture of New Orleans, Louisiana, and several land victories.[2] The strategic city of Vicksburg, Mississippi, was still in Confederate hands, and Union Navy elements were sent upriver from New Orleans in May to attempt to take the city, a move that was ultimately unsuccessful.[3] In late June, a joint army-navy expedition returned to make another attempt on Vicksburg.[4] Union Navy leadership decided that the city could not be taken without additional infantrymen, who were not forthcoming. An attempt to cut Williams's Canal across a meander of the river failed.[5][6]

In late November, Union infantry commanded by Major General Ulysses S. Grant began moving south towards Vicksburg from a starting point in Tennessee. However, he ordered a retreat after a supply depot and part of his supply line were destroyed during the Holly Springs Raid and Forrest's West Tennessee Raid. Meanwhile, another arm of the expedition under the command of Major General William T. Sherman left Memphis, Tennessee, on the same day as the Holly Springs Raid and travelled down the Mississippi River. After diverting up the Yazoo River, Sherman's men began skirmishing with Confederate soldiers defending a line of hills above the Chickasaw Bayou. A Union attack on December 29 was defeated decisively at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou, and Sherman's men withdrew on January 1, 1863.[7]

Prelude[]

In early 1863, Grant again began planning operations against Vicksburg. Some of these ideas included revisiting the old Williams's Canal attempt, cutting a canal near Lake Providence, Louisiana, and then navigating through bayous to bypass Vicksburg, a movement up the Yazoo River known as the Yazoo Pass Expedition, and another bayou navigation attempt known as the Steele's Bayou expedition.[8][9] By March 29, such alternative measures had failed, and Grant was left with a choice between three alternatives: attacking Vicksburg from directly across the river, pulling back to Memphis and then attacking overland from the north, or marching south on the Louisiana side of the river and then crossing the river below the city. Attacking across the river would have risked heavy casualties, and pulling back to Memphis could be interpreted as a retreat, which would be politically disastrous, leaving Grant to choose the southward movement. On April 29, Union Navy ships bombarded Confederate river batteries in the Battle of Grand Gulf as preparation for a crossing, but were unable to completely silence the position. In turn, Grant simply crossed his men the next day even further south, at Bruinsburg, Mississippi.[10]

Grant's men drove inland, and defeated a Confederate blocking force at the Battle of Port Gibson on May 1; the batteries at Grand Gulf were abandoned the next day.[11] Grant was then forced to make another choice: he could move north towards Vicksburg, or head east and later turn to the west and attack Vicksburg from that direction. Both lines of advance had the potential to capture the city, but the latter option provided a better chance of also capturing the Confederate garrison and its commander, Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton. Grant put his plan in motion by having Sherman's XV Corps cross the Mississippi River at the now-abandoned Grand Gulf position and then drive towards Auburn. To Sherman's left, Major General John A. McClernand's XIII Corps covered the crossing of the Big Black River, and on the Union right was Major General John B. McPherson's XVII Corps. McPherson, who was lacking experience leading a sizable body of men in independent command, was directed to advance to Raymond via Utica.[12][13][14] McPherson's advance was resisted by little other than militia. Union cavalrymen raided the New Orleans, Jackson and Great Northern Railroad, and the advance frightened local residents. On May 11, Grant ordered McPherson to take his command to Raymond and resupply there, while maintaining the impression that he was targeting Jackson.[15]

Pemberton responded to the Union movements by moving his forces north along the course of the Big Black River, shadowing the Union movements, but never crossing the river.[16] Meanwhile, reinforcements were brought up from elsewhere in the Confederacy and concentrated at Jackson. General Joseph E. Johnston was ordered on May 10 to travel to Jackson to command the growing force,[13] which would eventually amount to about 6,000 men.[17][18] One of these units was the brigade of Brigadier General John Gregg, which had been sent to Jackson from Port Hudson, Louisiana.[19] In his only aggressive action at the time,[16] Pemberton sent Gregg to Raymond with hopes of intercepting a Union unit rumored to be at Utica. Both Gregg and Pemberton believed that the Union force was only a single brigade, which would have numbered about 1,500 men, and that any advance against Raymond would only be a feint. In reality, the Union force at Utica was McPherson's corps, which numbered about 10,000 to 12,000 men.[20][21] Expecting the main Union assault to come at the Big Black River, Pemberton believed that any movements towards Jackson via Raymond were simply feints. He gave Gregg orders to fall back to Jackson if Union troops pushed through Raymond, but to attack the rear of Grant's line if the Union army pivoted towards the Big Black.[22]

Gregg and his men reached Raymond on May 11, expecting to find Colonel William Wirt Adams's Confederate cavalry in the town; Adams's men were to conduct reconnaissance. Instead, the only Confederate force in Raymond was a small command of 40 cavalrymen – mainly young locals –[23] and a separate five-man detachment. Gregg sent the 40-man unit down the road towards Utica, while keeping the five men for courier service.[20][24] Adams later sent a unit of 50 cavalrymen to aid Gregg; they arrived that night.[24] On the morning of May 12, the scouting force soon reported approaching Union soldiers,[25] and Gregg, still anticipating only a single Union brigade, prepared for battle with a force numbering around 3,000[20] to 4,000 men.[19] The scouts had been unable to provide an accurate count of Union strength. Believing that he could easily defeat the approaching enemy force, Gregg responded aggressively.[25]

He ordered Colonel Hiram Granbury to take the 7th Texas Infantry Regiment and the to a rise near the junction of the roads to Utica and Port Gibson.[26] The Texans were to attract Union attention and draw them into a cul-de-sac-shaped portion of Fourteenmile Creek.[27] Colonel Calvin H. Walker and the were sent to the back side of some high ground northeast of the brigade over Fourteenmile Creek. The and the moved down the Gallatin Road to the left. Gregg's plan was to contest his line with Walker's and Granbury's men and then have the Tennesseeans down the Gallatin Road conduct a flanking attack against the Union right.[26] Hiram Bledsoe's Missouri Battery and its three cannons was positioned with the 1st Tennessee Battalion and had orders to fire on any attempts to cross the bridge over the creek on the Utica Road.[15] The was held in reserve about 0.5 miles (800 m) behind the 3d Tennessee, near Raymond's cemetery. The line was stretched thin to cover the three roads and contained gaps between units.[28] Heavy undergrowth along the position restricted Gregg's ability to clearly observe the Union forces when the came, preventing an accurate assessment of McPherson's strength.[29]

Battle[]

The fighting opened on the morning of May 12 when the leading Union troops ran into skirmishers sent out by Granbury. The Union troops were surprised to meet resistance, and skirmishing began at a range of about 100 yards (91 m).[15] Bledsoe's cannons also began firing at the advancing Union troops,[30] and Union artillery began firing as well. Which side opened the battle is not known.[31] At around 09:00, McPherson realized that the Confederates in front of his force represented more than just skirmishers, and began deploying for battle. McPherson used cavalry to cover his flanks and brought Brigadier General Elias Dennis's brigade, which consisted of four regiments, three of which were from Ohio, to the front.[32][33] The six cannons of the 8th Michigan Light Artillery Battery[34] were brought up to duel Bledsoe's Battery.[35] Dennis's men forced the Confederates back and were able to send a skirmish line across the creek.[35] The 3rd Ohio Battery also arrived on the scene, strengthening the Union line, which now had a twelve to three advantage in cannons. Additionally, Union Brigadier General John E. Smith's five-regiment brigade of Logan's division arrived and attacked the Confederate line.[36] Of Smith's regiments, only the 23rd Indiana Infantry Regiment was successfully able to cross the creek; the rest became bogged down in the heavy undergrowth near the creek.[35][36] Logan's division was able to field about 6,500 men.[29]

With the Union troops concentrated on a single road, Gregg decided to pull his troops closer together and attack. His plan was for the 7th Texas and the 3rd Tennessee to attack en echelon. The 50th Tennessee and 10th and 30th Tennessee (Consolidated) were to move off of the Gallatin Road and strike the Union line in the flank, which Gregg expected to be exposed.[37] Between the two regiments, Gregg's flanking force was composed of roughly 1,200 men.[38] It was also hoped that the two flanking units could capture McPherson's artillery.[39] Gregg's Texans hit the 20th Ohio Infantry Regiment and the 68th Ohio Infantry Regiment hard. The former regiment held, but the latter broke for the rear.[40] Surprised, the Union line began to buckle, but was rallied by division commander Major General John A. Logan.[41][42] McPherson, in his inexperience, overestimated the strength of the Confederate force he was facing.[35] The 3rd Tennessee counterattacked the Indianans, who were driven back across the creek and reformed beside the 20th Ohio. The attacking Tennesseans shifted to the southeast and advanced towards the 45th Illinois Infantry Regiment.[43] Gregg brought the 41st Tennessee up from reserve, but did not scout the Union line, and was thus uninformed of the true Union strength;[35] he had interpreted Union movements from earlier in the battle as indicating that he was facing a small force.[38]

A third Union brigade, under the command of Brigadier General John D. Stevenson, had held back in the rear because of dust clouds kicked up by Smith's brigade. As the battle grew in intensity, Stevenson began moving his men to a position behind the 8th Michigan Battery, but was ordered by McPherson to support Dennis and Smith when the Confederate attack hit.[44] Stevenson's four regiments were split up, with two sent to support Smith and Dennis, and the others moving to shore up the Union right flank. The latter movement meant that Gregg's two flanking regiments would not strike an exposed Union position.[45] When some of the men of the 50th Tennessee opened fire on the Union line, the element of surprise was lost. The unit's commander also realized that the Union force was much larger than expected, and attempted to inform Gregg of this development. However, the messenger sent to find Gregg was unable to do so, and the message was not delivered. The unit then fell back to a defensive position without informing other Confederate units.[46] The commander of the 10th and 30th Tennessee (Consolidated) had orders to not enter the battle until after the 50th Tennessee had entered the fighting. Gregg's flank attack had stalled, with one unit hanging out of the fighting and the other waiting for the former to enter the battle.[47]

On the other end of the Confederate line, an attack by the 20th Illinois Infantry Regiment drove back the 7th Texas. At this point in the fighting, the lines had realigned so that the Union troops held the 125 yards (114 m) of the creek east of the bridge and fired north, while on the other side of a curve in the creek, the Confederates held 100 yards (91 m) and fired south.[46] Meanwhile, the 3rd Tennessee continued to advance, expecting that its left flank would be covered by the 50th Tennessee. With the latter unit not in position, the 3rd Tennessee's flank was exposed to fire from the 31st Illinois Infantry Regiment.[48][24] Union troops counterattacked the 3rd Tennessee with four regiments, and drove it back after a 45-minute fight, only to be staved off by the 41st Tennessee.[24] The 20th Ohio also attacked the 7th Texas. The Confederate unit retreated and split in two, with part falling back to the 1st Tennessee Battalion and the rest to the 10th and 30th Tennessee (Consolidated).[48] More Union artillery arrived on the field when four 24-pounder howitzers from an Illinois unit deployed.[49]

The battle was growing chaotic due to thick undergrowth and clouds of smoke, and units on both sides fought more and more individually with less direction from high-ranking officers.[30][21] At 13:30, a brigade from Union Brigadier General Marcellus M. Crocker's division, commanded by Colonel John B. Sanborn, arrived on the field at move to support Logan's left,[30] as McPherson expected that Sherman might arrive, and wanted to extend his line closer to Sherman's position.[50] Two regiments from Crocker's division were also sent to aid Smith and Stevenson, as the 7th Texas was withdrawing. A Union regimental commander determined that the two new regiments were not needed, and the reinforcements took a reserve position.[51] The 50th Tennessee and the 10th and 30th Tennessee (Consolidated) prepared to advance together, but paused to await further orders. The expected orders did not arrive, and the latter unit moved to the right, breaking contact between the two units. The men of the 50th Tennessee noticed the sound of heavy fighting to their right, and began to take fire from that direction.[52] The unit then fell back to its original position it had occupied in the morning.[51] Having either been ordered by Gregg to move to the center of the line,[51] or driven by Union troops towards that position, the 10th and 30th Tennessee (Consolidated) moved to a point in the line near where the 3rd Tennessee was fighting Smith's men.[53] The new deployment left a gap between the 10th and 30th Tennessee (Consolidated) and the 41st Tennessee.[51]

McPherson was able to bring up 22 cannons onto the field,[30] and some of his men forced their way across the creek, making contact with the 50th Tennessee. The Union artillery began to fire upon the exposed position of the 10th and 30th Tennessee (Consolidated). Knowing that a retreat would break the Confederate line, and that his men would suffer casualties if they remained steady, the unit's commander, Colonel Randal William MacGavock, ordered an attack against the 7th Missouri Infantry Regiment, which had recently crossed the creek. MacGavock was killed early in the charge, but his men were able to drive the Missourians back before a counterattack drove them back to their starting point.[24][54] Gregg did not know that his left flank was held by the 50th Tennessee, and ordered the 41st Tennessee in that direction. At the same time, the 50th Tennessee had begun moving on its own to the right, where the sounds of battle were coming from; the two regiments essentially switched places.[54]

The weight of superior Union numbers was beginning to tell.[21] Gregg determined that a retreat was necessary, and ordered the 1st Tennessee Battalion to bluff an attack against Crocker's men, covering the withdrawal of the spent 7th Texas and 3rd Tennessee.[55] The Union troops fell for the bluff and withdrew, allowing the 1st Tennessee Battalion to cover the Confederate retreat.[56] The 10th and 30th Tennessee (Consolidated) began to withdraw on its own, then attacked a Union regiment from Ohio, only to be driven back by additional Union forces.[55] The 50th Tennessee moved to the Utica Road during the retreat and covered it while falling back.[56] Six companies of the 3rd Kentucky Mounted Infantry Regiment arrived on the field unexpectedly, and helped cover the retreat.[55] The retreat occurred over two roads,[57] and Gregg's men fell back through the town of Raymond and onto the road to Jackson,[24][55] before stopping for the night in some woods near a local cemetery.[58] They were joined by 1,000 men under the command of Brigadier General W. H. T. Walker that evening.[59] Led by the 20th Ohio,[60] Fighting ended around 16:00,[61] and Union soldiers entered Raymond, where they found and consumed a meal of fried chicken and lemonade that area women had prepared for Gregg's men, expecting a Confederate victory. Gregg's men abandoned their wounded and fell back to Jackson the next day; McPherson did not pursue, citing the difficulty of the terrain.[58] Anne Martin, a civilian resident of Raymond, reported that the Union soldiers occupying the town looted her house and wrote a letter to a family member stating that she had heard sounds of similar destruction from elsewhere in the town.[62]

Aftermath[]

Reports of Union casualties vary between 442 and 446. The historians William L. Shea and Terrence J. Winschel support the latter number and break down casualties as 68 killed, 341 wounded, and 37 missing;[63] Donald L. Miller agrees with this total,[58] as well as the historian Timothy B. Smith.[61] The former figure is given by the historians Shelby Foote and Michael B. Ballard;[19][64] in one work, Ed Bearss also gives the total as 442 with a breakdown of 66 killed, 339 wounded, and 37 missing,[65] although he also supported the 446 figure in a different work.[60] Confederate losses are reported as either 514, with a breakdown of 72 killed, 252 wounded, and 190 missing,[65][19] or 515, with the extra loss being another man killed.[63][60] Another statement of Confederate casualties is provided by McPherson, who claimed to have captured 720 Confederates and found another 103 slain on the field.[64] Smith attributes the 515 figure to Gregg's post-battle report, and notes that the casualty figures were later updated by a small amount. He also states that it is likely that exact casualties suffered during the battle will never be known.[61] Confederate losses were heaviest in the 3rd Tennessee and the 7th Texas.[63] In addition to the human casualties, the Confederates also lost one of Bledsoe's cannons, which burst during the fighting.[51] Union wounded were treated in field hospitals set up in local churches, while a Confederate field hospital was run inside the Hinds County courthouse.[64] Union losses represented about three percent of McPherson's force, while Gregg lost about 16 percent of his.[66]

The fight at Raymond demonstrated to Grant that the Confederate force in Jackson was stronger than he had believed, leading him to decide that the Confederate forces there must be neutralized in order to be able to attack Vicksburg without the risk of being caught between two Confederate armies.[67] Thinking that McPherson's corps was insufficient to take Jackson on its own, Grant decided to bring his whole army to bear against the city, abandoning a previous plan to turn west and cross the Big Black River at Edwards and Bolton.[30] The previously planned movement was viewed as too risky with Johnston and the Jackson garrison left in the Union army's rear,[68] especially as McClernand's men had also encountered part of Pemberton's force during the battle at Raymond.[69] McClernand was ordered to move to Raymond, McPherson was to head northeast to Clinton and then strike Jackson, and Sherman was to approach the place from the southwest.[30]

On May 14, the Union army attacked Jackson. Johnston withdrew his men from the city, with Gregg performing rear guard duty.[18] Grant's army then turned west and encountered Pemberton's men, who were attempting to make a stand east of Vicksburg. On May 16, Pemberton' men were defeated at the Battle of Champion Hill, and after a defeat in a rear guard action at the Battle of Big Black River Bridge the next day, withdrew into the Vickburg defenses.[70][71] Union attempts to take the city by direct assault on May 19 and 22 failed, and Grant placed Vicksburg under siege. Supplies within the city eventually ran low, and with no hope of escape, Pemberton surrendered the city and his army on July 4, ending the Siege of Vicksburg. The capture of Vicksburg was a critical point in the war.[72]

Assessment[]

Modern historians have criticized McPherson's handling of the battle. Bearss described McPherson's handling of the battle as "not a success" and as "far too cautious or, perhaps worse, timid", citing his piecemeal deployment of his troops and ineffective use of his artillery advantage.[26][73] Miller also stated that McPherson mismanaged the battle and called the decision not to pursue a mistake.[58] Ballard concluded that McPherson had not formed an overall plan of command, instead just feeding troops into the fight and leaving tactical decisions to lower commanders. Ballard attributed the Union victory to numerical advantage, rather than McPherson's generalship.[64] Smith wrote that "McPherson did not earn high marks for the handling of his corps" and criticized him for allowing the Confederates to have the initiative for most of the fighting and for failing to properly coordinate his troops. He also believed that the Union general should have had plans for a pursuit.[61] Bearss also criticized Gregg for being too aggressive and failing to ascertain the strength of the force he was facing.[73] Conversely, Smith believed that Gregg "demonstrated real ability" in planning, use of discretion, and inspiring his men.[61] Alternatively, writer Kevin Dougherty attributes the Confederate defeat to Gregg's failure to gain an accurate assessment of McPherson's strength and the nature of the battlefield situation.[74]

Battlefield preservation[]

The site of the battle was listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) on January 13, 1972 as the .[75] The 1971 NRHP application form stated that the battlefield had been altered, but was still in good condition.[76] At that time, the site had both publicly- and privately-owned elements and had restricted access. Various parts of the battlefield were used for agricultural, residential, industrial, or transportation purposes.[77] Two iterations of Mississippi Highway 18 cut through the field. Construction of the newer iteration had required disinterring Confederate dead from a burial trench. The battlefield location of Bledsoe's battery had been covered over by an industrial facility, and the road to Utica was overgrown and no longer in use.[76] The listing encompassed 1,440 acres (580 ha) of the battlefield,[78] but only 936.42 acres (378.96 ha) were still listed in 2010.[79]

The Battle of Raymond is one of 16 American Civil War battle sites studied by the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission (CWSAC).[80] In 1993, a CWSAC study ranked the Raymond battlefield as in the tier of highest priority for protection.[81] A reenactment of the battle took place on the site in 2001.[82] In 2010, the site received another study, this time form the American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP). The ABPP study focused on 5,643.83 acres (2,283.98 ha) and deemed that 4,467.02 acres (1,807.74 ha) of them were potentially eligible for NRHP listing.[83] As of 2010, about 79 percent of the battlefield at Raymond was still considered intact,[81] including the Union artillery position, Fourteenmile Creek, and part of the Utica Road.[84] The Friends of Raymond group manages 135 acres (55 ha) of the site as the Raymond Military Park, providing public interpretation.[85] As of 2010, the interpretation included a walking trail and signage.[86] In December 2020, the Mississippi Department of Archives and History received a grant to purchase 43.71 acres (17.69 ha) at Raymond.[87]

Notes[]

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 117–118.

- ^ "The Long, Gruesome Fight to Capture Vicksburg". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 135–138.

- ^ Miller 2019, p. 153.

- ^ "Grant's Canal". National Park Service. October 25, 2018. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Winschel 1998, pp. 154, 156.

- ^ Miller 2019, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, p. 157.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Bearss 1998a, pp. 157–164.

- ^ Bearss 1998b, pp. 164–165.

- ^ a b Bearss 2007, p. 216.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b c Ballard 2004, p. 263.

- ^ a b Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 121.

- ^ Foote 1995, p. 189.

- ^ a b Kennedy 1998, p. 167.

- ^ a b c d Foote 1995, p. 178.

- ^ a b c Bearss 2007, pp. 216–217.

- ^ a b c Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 123.

- ^ Dougherty 2011, p. 137.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d e f Goodman 1997.

- ^ a b Ballard 2004, p. 261.

- ^ a b c Bearss 2007, p. 217.

- ^ Hills 2013, p. 86.

- ^ Smith 2012, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Dougherty 2011, p. 138.

- ^ a b c d e f Bearss 1998b, p. 166.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 73.

- ^ Ballard 2004, pp. 263–264.

- ^ Bearss 2007, pp. 217–218.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 74.

- ^ a b c d e Ballard 2004, p. 264.

- ^ a b Bearss 2007, p. 218.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 77.

- ^ a b Grabau 2000, p. 235.

- ^ Bearss 2007, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 78.

- ^ Shea & Winschel 2003, pp. 121, 123.

- ^ Ballard 2004, p. 265.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 80.

- ^ Ballard 2004, pp. 265–266.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 82.

- ^ a b Ballard 2004, p. 266.

- ^ Smith 2012, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b Ballard 2004, pp. 266–267.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 83.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 84.

- ^ a b c d e Ballard 2004, p. 267.

- ^ Smith 2012, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 85.

- ^ a b Ballard 2004, p. 268.

- ^ a b c d Ballard 2004, pp. 268–269.

- ^ a b Smith 2012, p. 87.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 86.

- ^ a b c d Miller 2019, p. 386.

- ^ Bearss 1998b, pp. 166–167.

- ^ a b c Bearss 2007, p. 220.

- ^ a b c d e Smith 2012, p. 88.

- ^ Carter 1980, p. 190.

- ^ a b c Shea & Winschel 2003, p. 124.

- ^ a b c d Ballard 2004, p. 269.

- ^ a b Bearss 1998b, p. 167.

- ^ Hills 2013, p. 87.

- ^ Smith 2012, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Miller 2019, p. 387.

- ^ Smith 2012, p. 89.

- ^ Bearss 1998c, pp. 167–170.

- ^ Kennedy 1998, p. 171.

- ^ Bearss 1998d, pp. 171–173.

- ^ a b Bearss 1998b, p. 165.

- ^ Dougherty 2011, pp. 137–140.

- ^ "National Register Database and Research". National Park Service. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ a b Wright 1971, p. 2.

- ^ Wright 1971, p. 1.

- ^ Wright 1971, p. 4.

- ^ National Park Service 2010, p. 20.

- ^ National Park Service 2010, p. 5.

- ^ a b National Park Service 2010, p. 6.

- ^ Walker, James (May 6, 2001). "Battle of Raymond Rages Again". The Clarion Ledger. Jackson, Mississippi. pp. A1. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ National Park Service 2010, p. 13.

- ^ National Park Service 2010, pp. 17–18.

- ^ National Park Service 2010, p. 23.

- ^ National Park Service 2010, p. 24.

- ^ Surratt, John (December 11, 2020). "NPS Grant to Help Preserve Battle Sites at Raymond, Military Park". The Vicksburg Post. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

References[]

- Ballard, Michael B. (2004). Vicksburg: The Campaign that Opened the Mississippi. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2893-9.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (1998). "Port Gibson, Mississippi". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 158–164. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (1998). "Raymond, Mississippi". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 164–167. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (1998). "Champion Hill, Mississippi". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 171–173. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (1998). "Battle and Siege of Vicksburg, Mississippi". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 164–167. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Bearss, Edwin C. (2007) [2006]. Fields of Honor. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. ISBN 978-1-4262-0093-9.

- Carter, Samuel (1980). The Final Fortress: The Campaign for Vicksburg 1862–1863. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 031283926X.

- Dougherty, Kevin (2011). The Campaigns for Vicksburg 1862–1863: Leadership Lessons. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Casemate. ISBN 978-1-61200-014-5.

- Foote, Shelby (1995) [1963]. The Beleaguered City: The Vicksburg Campaign (Modern Library ed.). New York: The Modern Library. ISBN 0-679-60170-8.

- Goodman, Al W. (September 1997). "Brutal Battle of Raymond". America's Civil War. 10 (4). ISSN 1046-2899.

- Grabau, Warren (2000). Ninety-eight Days: A Geographer's View of the Vicksburg Campaign. Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 9781572330689.

- Hills, J. Parker (2013). "Roads to Raymond". In Woodworth, Stephen D.; Grear, Charles D. (eds.). The Vicksburg Campaign: March 29–May 18, 1863 (ebook ed.). Carbondale, Illinois: Southern Illinois University Press. pp. 65–95. ISBN 978-0-8093-3270-0.

- Kennedy, Frances H., ed. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Miller, Donald L. (2019). Vicksburg: Grant's Campaign that Broke the Confederacy. New York, New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4516-4139-4.

- Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation's Civil War Battlefields: State of Mississippi (PDF). Washington, D. C.: National Park Service. October 2010. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- Shea, William L.; Winschel, Terrence J. (2003). Vicksburg Is the Key: The Struggle for the Mississippi River. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-9344-1.

- Smith, Timothy B. (2012) [2006]. Champion Hill: Decisive Battle for Vicksburg. El Dorado Hills, California: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-932714-19-7.

- Winschel, Terrence J. (1998). "Chickasaw Bayou, Mississippi". In Kennedy, Frances H. (ed.). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Boston/New York: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 154–156. ISBN 978-0-395-74012-5.

- Wright, William C. (June 18, 1971). National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form (PDF). Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

Further reading[]

- Barber, Flavell C., and Ferrell, Robert H., Holding the Line: The Third Tennessee Infantry 1861–1864, Kent State University Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0-87338-504-6.

External links[]

American Civil War portal

American Civil War portal

- The Raymond Battlefield: Then & Now – An interview with Parker Hills

- Order of Battle

- Friends of Raymond

Coordinates: 32°14′21″N 90°26′55″W / 32.23917°N 90.44861°W

- Vicksburg campaign

- Battles of the Western Theater of the American Civil War

- Union victories of the American Civil War

- Battles of the American Civil War in Mississippi

- Hinds County, Mississippi

- 1863 in Mississippi

- May 1863 events

- 1863 in the American Civil War

- National Register of Historic Places in Hinds County, Mississippi