Battle of São Vicente

| Battle of São Vicente | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Anglo–Spanish War | |||||||

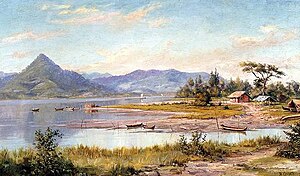

Painting of the Bay of São Vicente by Benedito Calixto | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Edward Fenton | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3 galleons |

2 galleons 1 pinnace | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 galleon sunk 1 galleon heavily damaged[3] 36 killed and 100 wounded[4] | 8 killed and 20 wounded[5][6] | ||||||

The Battle of São Vicente was a minor naval engagement that took place off São Vicente, Portuguese Brazil on 3 February 1583 during the Anglo–Spanish War between three English ships (including two galleons), and three Spanish galleons.[2] The English under Edward Fenton on an expedition having failed to enter the Pacific, then attempted to trade off Portuguese Brazil but were intercepted by a detached Spanish squadron under Commodore .[7] After a moonlit battle briefly interrupted by a rainstorm the Spanish were defeated with one galleon sunk and another heavily damaged along with heavy losses.[6][8] Fenton then attempted to resume trading but without success and thus returned to England.[9][10]

Background[]

In June 1582 after a troublesome delay, an English expedition had set off to reach the South China Sea via the Cape of Good Hope on a voyage of exploration.[11] Their commander was Captain Edward Fenton with his 400-ton flagship galleon Leicester (ex-galleon Bear) under second-in-command Sir William Hawkins Jr (the nephew of Sir John Hawkins).[12] Following Fenton was the 300-ton vice-flagship Edward Bonaventure under Luke Warde; the 50-ton pinnace Elizabeth under Thomas Skevington and the 40-ton bark Francis under John Drake (Sir Francis Drake’s nephew).[11] The fleet's chaplain Richard Madox recorded the events of the voyage in a diary.[8]

On 11 December 1582 Fenton arrived off Portuguese Brazil, the original plan having been changed with the hope of going through the Straits of Magellan instead of the Cape.[13] On 17 December, after having refreshed with victuals ashore the English sighted and then captured the 46-ton Spanish bark Nuestra Señora de Piedad.[14] The ship was bound from Brazil towards the River Plate with twenty one settlers under .[8] From the Spaniard they had learned of Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa's departure from Rio de Janeiro to fortify the Strait of Magellan.[12] Three days later the English released their prize and by the 31st were unsure of being able to win past Sarmiento's new settlement in the Strait.[13] Fenton after heated discussion with Hawkins reversed course the same evening, and headed north towards São Vicente hoping to do trade with the settlers there.[3] The same night a storm dispersed the ships resulting in the loss of John Drake's eighteen-man Francis, never to be seen or heard of again.[7]

On 30 January 1583 Fenton reached the bay of São Vicente with Leicester, Edward Bonaventure, and Elizabeth, and were in talks with the Portuguese residents of nearby Santos.[12] Trade was refused on the account that Spain would react to this as hostile as they were now in Union; Fenton then went on to São Vicente itself hoping for better fortune.[11]

Battle[]

On 3 February three Spanish galleons; the largest being the 500-ton San Juan Bautista, the 400-ton Santa María de Begona and the 300-ton Concepción, entered the bay of São Vicente.[5][15] They had been detached from the fleet of (Sarmiento's second-in-command) at Santa Catarina Island to return to Rio de Janeiro.[12] Led by Commodore Andrés de Equino, they had some of the sick and injured from the Spanish expedition.[4] They knew of the presence of the English ships by way having caught up with the Piedad that had been released by them.[12]

At 11 pm in the moonlight, Equino had cleared for battle, stood in and bore down upon the three English ships.[12] The English were surprised with many still on shore in the dark but as the Spanish approached, they placed and anchored themselves in seven fathoms of water just off a sandbar.[1] Spanish combat tactics during this time was an attempt to grapple and then board.[3] English tactics on the other hand was the heavy use of firepower to batter opponents into submission.[8]

The Leicester being the main ship that stood the nearest as they approached opened a heavy fire.[6] The Spanish ships were repelled and then tried to pass Leicester and move onto the next ship Edward Bonaventure.[8] They were again repelled with heavy fire from the English cannons.[5] The moonlit exchange continued with the English ships standing their ground and repelling the Spanish until about 4 am, when a rainstorm interrupted the battle.[12] The Spanish ceased fire and moved off to effect repairs, with the English doing the same and collecting the rest of the men onshore.[4]

Both sides had no idea what damage they had done to each other until dawn broke the next day; the English as a result of their firepower could then see that the Spanish ship Begonia had sunk[15] revealing only her masts in the shallow water.[5] This time in daylight at 10 am Equino's two galleons attacked but were repelled again by the anchored English ships.[1][6]

Finally the Spaniards with rising casualties and a lack of ammunition then broke off the fight, then stood out to sea before retreating down the Santos river.[5][7] Fenton's ships also running low on ammunition had been victorious and stayed put on the bar for the time being.[3][4]

Aftermath[]

The battle had only cost eight Englishmen killed and twenty injured and only moderate damage to their ships.[6][16] An Indian who went aboard the Leicester told Fenton that the Spanish who had landed at Santos further down had suffered heavily.[8] As well as Begonia sunk with the loss of 32 men killed,[15] the galleon Concepción was heavily damaged bringing the total to nearly a hundred dead and many more wounded.[3] The Indian also said that the Spanish had carried the casualties to the shore in three small boats a number of times.[4]

Fenton's ships stayed at São Vicente for only the rest of the day trying to at least do some trade but the Portuguese answer was the same as before.[14] Fenton fearing more Spanish ships then moved off to Espirito Santo where news of the battle had been received but with mixed feelings with the populace; trade was again refused.[17] Disappointed, Fenton realized that trade with the Portuguese here was at an end.[9] With supplies running low and quarrels with Hawkins decided to sail for England.[7] Spanish sources argue that even if defeated, de Equino's action was pivotal in Fenton's decision to withdraw.[15]

Warde's Edward Bonaventure got separated from its consorts on 8 February and sailed alone towards England.[12] After touching at Fernando de Noronha Island; Fenton then reached Salvador to refresh before returning to England.[6] Richard Maddox died on the 27th but his diary proved invaluable and is now preserved at the British Museum.[18]

References[]

- Citations

- ^ a b c Dean 2013, p. 153.

- ^ a b Wilgus, Alva Curtis (1941). The Development of Hispanic America. Farrar & Rinehart, Incorporated. p. 181.defeated a Spanish squadron at Sao Vicente

- ^ a b c d e Bicheno 2012, p. 170.

- ^ a b c d e Taylor, Eva G. R. (1959). The Troublesome Voyage of Captain Edward Fenton, 1582-1583: Narratives & Documents Volume 113 of Works issued by the Hakluyt Society. Hakluyt Society. pp. 129–30.

- ^ a b c d e Martin & Wignall 1975, p. 256.

- ^ a b c d e f Bradley 2010, pp. 377–79.

- ^ a b c d Andrews 1984, pp. 163–64.

- ^ a b c d e f Madoz, Richard (1976). An Elizabethan in 1582: The Diary of Richard Madox, Fellow of All Souls Volume 147. University of Texas: Hakluyt Society. p. xiii. ISBN 9780904180046.

- ^ a b Richard Hakluyt, Principal Navigations, iii. 757.

- ^ Varnhagen, Francisco Adolfo de (1981). História geral do Brasil: antes da sua separação e independência de Portugal. Editora Itatiaia. p. 378. (Portuguese)

- ^ a b c Taylor, Eva G. R. (1959) pp 50-59

- ^ a b c d e f g h Marley 2008, pp. 113–14.

- ^ a b Bradley 2010, pp. 374–76.

- ^ a b Dutra 1980, p. 130.

- ^ a b c d Fernández Duro, Cesáreo: Armada española desde la unión de los reinos de Castilla y de Aragón. Vol. II. Instituto de Historia y Cultura Naval, p. 365 (Spanish)

- ^ Calendar of State Papers: Preserved in the State Paper Department of Her Majesty's Record Office. Colonial series, Volume 2. H.M. Stationery Office. 1862. p. 91.

- ^ Ebert 2008, p. 142.

- ^ Boas 2013, p. 160.

- Bibliography

- Andrews, Kenneth (1984). Trade, Plunder and Settlement: Maritime Enterprise and the Genesis of the British Empire, 1480-1630. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521276986.

- Bicheno, Hugh (2012). Elizabeth's Sea Dogs: How England's Mariners Became the Scourge of the Seas. Conway. ISBN 978-1844861743.

- Boas, Frederick S (2013). University Drama in the Tudor Age. HardPress. ISBN 9781313132060.

- Bradley, Peter T (2010). British Maritime Enterprise in the New World: From the Late Fifteenth to the Mid-eighteenth Century. Edwin Mellen Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0773478664.

- Dean, James Seay (2013). Tropics Bound: Elizabeth's Seadogs on the Spanish Main. History Press. ISBN 9780752496689.

- Dutra, Francis A (1980). A guide to the history of Brazil, 1500-1822: the literature in English. ABC-Clio. ISBN 9780874362633.

- Ebert, Christopher (2008). Between Empires: Brazilian Sugar in the Early Atlantic Economy, 1550-1630 Volume 16 of The Atlantic world. Brill. ISBN 9789004167681.

- Marley, David (2008). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the Western Hemisphere. ABC CLIO. ISBN 978-1598841008.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Fenton, Edward". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Martin & Wignall, Colin & Sydney (1975). Full Fathom Five: Wrecks of the Spanish Armada. Chatto & Windus. ISBN 9780701120719.

- Naval battles of the Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604)

- Conflicts in 1583

- Naval battles involving Spain

- Naval battles involving England

- Colonial Brazil

- 1583 in the British Empire

- 1583 in the Spanish Empire

- 1583 in South America