Battle of Wyoming

| Battle of Wyoming Valley | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

Depiction of the battle by Alonzo Chappel, 1858 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Iroquois |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Sayenqueraghta Cornplanter |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

110 Butler's Rangers 464 Iroquois (primarily Seneca, but also Cayuga, Onondaga, Lenape, and Tuscarora)[1] |

360 (24th regiment Connecticut militia, detachment of Continentals, Wyoming riflemen) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

3 killed 8 wounded |

about 340 killed[2] 5-20 captured | ||||||

The Battle of Wyoming (also known as the Wyoming Massacre) was an encounter during the American Revolutionary War between American Patriots and Loyalists accompanied by Iroquois raiders which took place in the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania on July 3, 1778, in Exeter and Wyoming, Pennsylvania. More than 300 Patriots were killed in the battle.

After the battle, settlers claimed that the Iroquois raiders had hunted and killed fleeing Patriots, then committed ritual torture against 30 to 40 who had surrendered, until they died.[3]

Background[]

In 1777, British general John Burgoyne led the Saratoga campaign to gain control of the Hudson River during the American Revolutionary War. He was weakened by loss of time and men after the Battle of Oriskany and was forced to surrender after the Battles of Saratoga in October. News of his surrender prompted France to enter the war as an American ally. The British were concerned that the French might attempt to retake parts of New France which they had lost in the French and Indian War, so they adopted a defensive strategy in Quebec. They recruited Loyalists and enlisted Indian allies to conduct a frontier war along the northern and western borders of the Thirteen Colonies.[4]

Colonel John Butler recruited a regiment of Loyalists, Seneca chiefs Sayenqueraghta and Cornplanter recruited primarily Seneca warriors, and Joseph Brant recruited mostly Mohawks, for a guerrilla war against the American frontier settlers. By April 1778, the Senecas were raiding settlements along the Allegheny and Susquehanna rivers, and the three groups met at the Indian village of Tioga, New York, in early June. Butler and the Senecas decided to attack the Wyoming Valley, while Brant and the Mohawks targeted settlements farther north.[5]

American military leaders, including George Washington and Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, sought to recruit Iroquois primarily as a diversion to keep the British busy in Quebec. These recruitment attempts, however, met with more limited successes. The Oneidas and Tuscaroras were the only tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy to become Patriot allies.[6]

Battle[]

The British forces arrived in the valley on June 30, having alerted the settlers to their approach by killing three men working at an unprotected gristmill on June 28. The next day, Colonel Butler sent a surrender demand to the militia at Wintermute's (Wintermoot) fort. Terms were arranged in which the defenders would surrender the fort with all their arms and stores and would then be released on the condition that they not bear arms again during the war. On July 3, however, the British saw that the defenders were gathering in great numbers outside of Forty Fort. William Caldwell was engaged in destroying Jenkin's fort with the American militia a mile away, so Butler organized an ambush. He ordered Fort Wintermute to be set on fire, and the Patriots believed that it signified a British retreat and advanced rapidly. Butler told the Seneca to lie flat on the ground so as not to be seen. The militia advanced to within a hundred yards of the British rangers and fired three volleys at them. The Seneca rose to their feet, fired one time, and then charged to engage in hand-to-hand combat.[7]

The battle lasted about 45 minutes. An order to reform the Patriot line instead turned into a frantic rout, as the inexperienced militiamen panicked and began to run. It became a deadly race from which only about 60 Patriots escaped. The Loyalists and Iroquois killed almost all who were captured, and only five prisoners were taken alive. Butler reported that his Indian allies had taken 227 scalps.[8]

The next morning, Colonel Nathan Denison agreed to surrender Forty Fort and two other posts, along with what remained of his militia. Butler paroled them on their promise to take no part in further hostilities. The British spared non-combatants, although they molested a few inhabitants after the forts' surrender.[9] Colonel Butler wrote:

But what gives me the sincerest satisfaction is that I can, with great truth, assure you that in the destruction of the settlement not a single person was hurt except such as were in arms, to these, in truth, the Indians gave no quarter.[10]

An American farmer wrote: "Happily these fierce people, satisfied with the death of those who had opposed them in arms, treated the defenseless ones, the woman and children, with a degree of humanity almost hitherto unparalleled".[11] According to one source, 60 Patriot bodies were found on the battlefield and another 36 on the line of retreat. All were buried in a common grave.[12]

Aftermath[]

John Butler reported only two Loyalist Rangers and one Indian killed out of 1,000 men, and eight Indians wounded. He claimed that his force took 227 scalps, burned 1,000 houses, and drove off 1,000 cattle plus many sheep and hogs. Only about 60 of the 300 militiamen and 60 Continentals escaped the disaster,[13] though Graymont states about 340 were killed.[2] John Butler and his forces would leave the valley and return to Fort Niagara by mid-July 1778.[14]

Lt. Col. George Dorrance was captured in the battle. On the 4th, as the victors were moving down to Forty Fort, the captors of Col. Dorrance, two Indians, started to take him down to that post. Being an officer of prominence, dressed in a new uniform, with new sword and equipments, he had been spared under the idea that more could be obtained for his ransom than could be made from his slaughter. About a mile from the field he became exhausted, and was unable to proceed farther. They put him to death, one taking his scalp and sword, the other his coat and cocked hat with feather. One of the Indians went through the fort showing off this clothing and took particular pains to exhibit himself to Mrs. Dorrance, who sat grieving over the sad fate of her husband. [15]

In the aftermath of the battle, many pro-American settlers fled the Valley and spread news and rumors about the American defeat that contributed to a general panic across the frontiers of New York and Pennsylvania. Some American newspapers picked up these rumors and went even further, producing unsubstantiated accounts about the burning of women, children, and wounded soldiers inside Forty Fort on the day after the battle (July 4).[16] The American public was outraged by such reports of a massacre and other atrocities. Many saw it as just one more reason to support American independence.[17]

A few months later, Colonel Thomas Hartley arrived with Hartley's Additional Continental Regiment to defend the valley and try to harvest some crops.[18][19] They were joined by a few militia companies, including that of Captain Denison. In September, Hartley and Denison ascended the east branch of the Susquehanna with 130 soldiers, destroying Indian villages as far as Tioga and recovering a large amount of plunder taken during the raid. They skirmished with the hostile Indians and withdrew when they learned that Joseph Brant was assembling a large force at Unadilla.[20]

Connecticut Continentals led by Captain Jeremiah Blanchard and Lieutenant Timothy Keyes held a fort in Pittston, several miles away from the battlefield. A group of British soldiers took over the fortress on July 4, 1778, one day after the Battle of Wyoming, and some of it was destroyed. Two years later, the Continentals stormed the fortification and recaptured it. It remained under Patriot control until the end of the war.[21]

Many Seneca Indians were angered by the accusations of atrocities committed at Wyoming, which they denied committing. Coupled with anger at American militiamen ignoring their paroles, such accusations led some native warriors under Joseph Brant and Walter Butler to attack civilians at the Cherry Valley massacre in November 1778.[22][23]

The Battle of Wyoming and the massacre at Cherry Valley encouraged American military leaders to strike back on the frontier. In the summer of 1779, the Sullivan Expedition, commissioned by General George Washington, methodically destroyed 40 Iroquois villages and an enormous quantity of stored corn and vegetables throughout upstate New York. The Iroquois never recovered from the damage inflicted by Sullivan's soldiers, and many died of starvation that winter. The tribes allied with the British continued to raid Patriot settlements until the end of the war.[24]

Legacy[]

The battle and massacre remained well-known to most Americans for the rest of the eighteenth century and for most of the nineteenth.[25] It particularly reemerged in national discourse during the War of 1812 when Americans again found themselves fighting the British and Native Americans on the frontier. Some contemporary newspaper accounts readily compared the Battle of Frenchtown (also known as the River Raisin Massacre) in 1813 to the Wyoming Massacre.[26]

The massacre was depicted by the Scottish poet Thomas Campbell in his 1809 poem "Gertrude of Wyoming". Because of the atrocities involved, Campbell described Joseph Brant as a "monster" in the poem, although it was later determined that Brant was not present.[27] Brant was at Oquaga on the day of the attack.[citation needed]

The western state of Wyoming received its name from the U.S. Congress when it became the Wyoming Territory in 1868.[28]

The battle and massacre is commemorated each year by the Wyoming Commemorative Association, a local non-profit organization, which holds a ceremony on the grounds of the monument dedicated to the battle. The Wyoming Monument is the site of a mass grave containing the bones of many of the victims of the battle and massacre. The commemorative ceremonies began in 1878, to mark the 100th anniversary of the battle and massacre. The principal speaker at the event was President Rutherford B. Hayes.[29] During the 100th anniversary commemoration, the people of Wyoming Valley used the motto "An honest tale speeds best when plainly told" in an effort to promote the historical account of the battle.[30]

The annual program has continued each year since then on the grounds. One hundred and seventy-eight names of Patriots killed in the battle are listed on the Wyoming Monument, and the names of about a dozen militia who were killed or died in captivity a day or so prior to the main battle. A possible explanation for the difference between the number of names on the monument (178) and the reported number of scalps taken in the battle (227) is that allegedly numerous civilians (perhaps as many as 200)—instead of surrendering to Colonel Butler—elected to flee and died of exposure in a swamp known as the "Shades of Death" after the battle.[31]

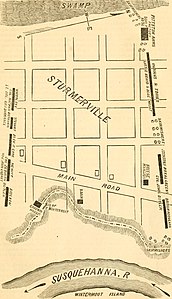

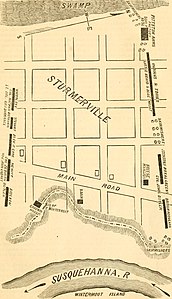

Wyoming forts: A-Fort Durkee, B-Fort Wyoming or Wilkesbarre, C-Fort Ogden, D-Kingston Village, E-Forty Fort, G-battleground, H-Fort Jenkins, I-Monocasy Island, J-Pittstown stockades, G-Queen Esther's Rock[32]

A historical sketch of the battlefield (one hundred years after the battle).

Battle of Wyoming Marker

The Wyoming Monument

The monument at night

Mouth of one of the cannons at the monument

Order of battle[]

In the battle:

- "Regular" Company commanded by Captain Dethie Hewitt † {40-44 men} {Reportedly only 15 of Company survived}.[33][nb 1]

- Shawnee Company commanded by Captain Asaph Whittlesey † at Forty Fort {44 men}

- Hanover Company commander Captain Wm McKarrchen †; but commanded by Captain Lazarus Stewart †;Lt Lazarus Stewart Jr †{30-40 men}

- Lower Wilkes-Barre Company commanded by Captain James Bidlack Jr. † at Wilkes-Barre {38 Men}

- Upper Wilkes-Barre Company commanded by Captain Rezin Geer † at Wilkes-Barre {30 men}

- Kingston Company commanded by Captain Aholiab Buck † at Forty Fort {44 men}

- It is also alleged there were about 100 men neither mustered nor enrolled.[12]

- Connecticut Militia: Lt Elijah Shoemaker †; Lt Asa Stevens †;

- Pennsylvania Militia: Lt. Daniel Gore {wounded-lost an arm}; Ensign Silas Gore †;

- Rolls of Durkee's; Ransom's; Spaulding Companies.[34]

- Independent Company aka Wyoming Valley Company {Consolidated with Ransom Company}-commanded by Captain Robert Durkee † {resigned June 23, 1778}; Lt James Wells † {85 men-not counting Durkee} {5 reported killed at Wyoming}

- Independent Wyoming Valley Company-commanded by Captain Samuel Ransom †; 1st Lt Perin Ross † {resigned Oct 25, 1777}; 2nd Lt Timothy Pierce † {Pierce also reported part of Spaulding Company}; {58 men-not counting Ransom and Pierce; 4 reported killed at Wyoming. In addition Heitman's register reports Ross killed in battle}.

- The following units did not take part in the battle:

- Consolidated Company from Ransom and Durkee companies commanded by Captain Simon Spaulding. {1st Lt-became captain June 24, 1778-d.Jan 24, 1814}; {Note: Spaulding Company formed under Congress June 23, 1778, reuniting Durkee and Ransom companies} {92 men; besides Pierce one reported killed; one wounded and scalped; one wounded and four sick. Although it had casualties from the battle, reportedly this company was either 24 miles at Bear Creek or 35 miles at Merwin's the night of the battle and helped bury the dead several weeks after the battle. Another source reports this company with a total of 69 names with 1 name erased; that 27 were of Ransom and 30 of Burkee's companies; and of whom 4 were killed at Wyoming.[36]}

- Pittston Company commanded by Captain Jeremiah Blanchard at Pittston Fort {40 men}

- Huntington and Salem Company commanded by Captain John Franklin at Home {35 men}

Reenactment of the Battle of Wyoming[]

Traditionally on the Fourth of July, every year for the past 140 years members of the Wyoming community and Luzerne County Historical Society have organized a ceremony reenacting the battle.[citation needed]

See also[]

- Protection of the Flag Monument (Bradford County, Pennsylvania)

References[]

Notes[]

- ^ Allegedly only one name known for this company.[34] There were at least two other names for this unit: Lt. Matthias Hollenback {Survived}[35] and Hugh Forsman.[33]

Citations[]

- ^ Nester, p. 201

- ^ Jump up to: a b Graymont, p. 171

- ^ Baillie, William. "The Wyoming Massacre and Columbia County". Columbia County Historical and Genealogical Society. Archived from the original on April 28, 2003. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ Nester, p. 189

- ^ Nester, p. 191

- ^ Calloway, Collin G. (December 4, 2008). "American Indians and the American Revolution". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

The Revolution split the Iroquois Confederacy. Mohawks led by Joseph Brant adhered to their long-standing allegiance to the British, and eventually most Cayugas, Onondagas, and Senecas joined them. But Oneidas and Tuscaroras sided with the Americans...

- ^ William R. Tharp, "'Savage and Bloody Footsteps Through the Valley': The Wyoming Massacre in the American Imagination," (M.A. thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2021), 22-28.

- ^ Cruikshank, pg. 47

- ^ Graymont, p. 172

- ^ Cruikshank, p. 49

- ^ Commager, p. 1010

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jenkins, Steuben (July 3, 1878). Historical Address at the Wyoming Monument (Speech). 100th Anniversary of the Battle and Massacre of Wyoming. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- ^ Boatner (1994), p. 1227

- ^ Tharp, "Savage and Bloody Footsteps Through the Valley," 32.

- ^ "Battle and Massacre af Wyoming: Luzerne Co., PA".

- ^ Tharp, "Savage and Bloody Footsteps Through the Valley," 32-49.

- ^ Tharp, "Savage and Bloody Footsteps Through the Valley," 51-54.

- ^ Boatner (1994), p. 1226.

- ^ Wright (1989), p. 322.

- ^ Boatner (1994), p. 1226

- ^ "Pittston City In Colonial America and the American Revolution".

- ^ Graymont, p. 174

- ^ Tharp, "Savage and Bloody Footsteps Through the Valley," 56-57.

- ^ Boatner (1994), pp. 1075-1076

- ^ Tharp, "Savage and Bloody Footsteps Through the Valley," 5-18, 58, 140.

- ^ Tharp, "Savage and Bloody Footsteps Through the Valley," 59-96, esp. 86-87.

- ^ Graymont, pg. 162

- ^ Brown, Jim (2014). "The First Wyoming: What's In a Name?". WyoHistory.org.

- ^ Hayes, Rutherford (July 7, 1878). The Diary and Letters of Rutherford B. Hayes, Nineteenth President of the United States. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State Archeological and Historical Society.

July 7, 1878. We enjoyed our trip to Wyoming [...] On the third we reached Mr. Pettibone's in Wyoming near the monument, about 9 A. M. or earlier. I spoke in the tent offhand, but acceptably. (pp. 488-490)

- ^ Francavilla, Lisa. The Wyoming Valley Battle and 'Massacre': Images of a Constructed American History (2002): ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. Web.

- ^ Richards, Henry Melchior Muhlenberg; Buckalew, John M.; Sheldon Reynolds; Jay Gilfillan Weiser; George Dallas Albert (1896). Report of the Commission to Locate the Site of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania. 1. Pennsylvania Commission to Locate the Site of the Frontier Forts of Pennsylvania. p. 1. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- ^ [Benson Lossing "The Pictorial Field-Book of the Revolution" Harper & Brothers, Publisher 1859 p.353]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hayden, Horace Edwin (1895). The Massacre of Wyoming: The Acts of Congress for the Defense of the Wyoming Valley, Pennsylvania, 1776–1778. Wyoming Historical and Geological Society. p. 57.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hazard, Samuel; Linn, John Blair; Egle, William Henry (1880). Pennsylvania Archives. J. Severns & Company. p. 116. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- ^ Murray, Louise Welles (1908). A History of Old Tioga Point and Early Athens, Pennsylvania. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: The Raeder Press. p. 241. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- ^ Dean, John Ward; Folsom, George; Shea, John Gilmary; Henry Reed Stiles; Henry Barton Dawson (1862). The Historical Magazine and Notes and Queries Concerning the Antiquities, History and Biography of America. Henry B. Dawson. p. 1. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

Bibliography[]

- Blackburne, C. (2019). Remembering the Revolutionary War Battle of Wyoming Like it Was Yesterday. [online] Wnep.com. Available at: https://wnep.com/2018/07/04/remembering-the-revolutionary-war-battle-of-wyoming-like-it-was-yesterday/ [Accessed 25 Feb. 2019].

- Boatner, Mark M. (1966). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. New York: D. McKay Co.

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1994). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.

- Commager, Henry; Morris, Richard (1958). The Spirit of Seventy-Six.

- Cruikshank, Ernest (1893). Butler's Rangers and the Settlement of Niagara.

- Francavilla, Lisa A. “The Wyoming Valley Battle and ‘Massacre’: Images of a Constructed American History.” M.A. thesis, College of William and Mary, 2002.

- Graymont, Barbara (1972). The Iroquois in the American Revolution. Syracuse, N.Y.: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-0083-6.

- Nester, William (2004). The frontier war for American independence. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0077-1.

- Pitcavage, B. (2019). Reenactment of the Battle of Wyoming is a Fourth of July tradition. [online] Citizensvoice.com. Available at: https://www.citizensvoice.com/arts-living/reenactment-of-the-battle-of-wyoming-is-a-fourth-of-july-tradition-1.2356477 [Accessed 25 Feb. 2019].

- Tharp, William R. “‘Savage and Bloody Footsteps Through the Valley’ : The Wyoming Massacre in the American Imagination." M.A. thesis, Virginia Commonwealth University, 2021.

- Williams, Glenn F. (2005). Year of the Hangman: George Washington's Campaign Against the Iroquois. Yardley, Pa.: Westholme. ISBN 1-59416-013-9.

- Wright, Robert K. Jr. (1989). The Continental Army. Washington, D.C.: US Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 60-4.

Further reading[]

- Altsheler, Joseph A. (1911). The Scouts of the Valley: A Story of Wyoming and the Chemung. New York: D. Appleton.

- Miner, Charles (1845). History of Wyoming. Philadelphia: J. Crissy.

Charles Miner.

External links[]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Major John Butler's Report of July 3, 1778

- Luzerne Co Gen Web on Wyoming Massacre

- Battle of Wyoming account

- John Durkee's Men of Wyoming

- Matthias Hollenback, Revolutionary War soldier, survivor of Wyoming Massacre, merchant, judge

- Hanover Twp History and Wyoming Battle

- Wilkes-Barre History

- Battle of Wyoming

- Mead family and the Wyoming Battle

- Gertrude of Wyoming by Thomas Campbell

- Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission | The Battle of Wyoming and Hartley's Expedition

- Indians in Pennsylvania - Google Books p. 162–164

- Wyoming Massacre at Find A Grave

- Former President Jimmy Carter speaks at Wyoming Monument on May 28, 2013 (archived on C-SPAN)

Coordinates: 41°19′14″N 75°49′08″W / 41.32056°N 75.81889°W

- 1778 in the United States

- Conflicts in 1778

- Battles in the Northern theater of the American Revolutionary War after Saratoga

- Battles of the American Revolutionary War in Pennsylvania

- Massacres by Native Americans

- History of Luzerne County, Pennsylvania

- 1778 in Pennsylvania

- Battles involving the Iroquois

- Massacres in the American Revolutionary War