Battle of the Indus

| Battle of the Indus | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol invasion of Central Asia | |||||||||

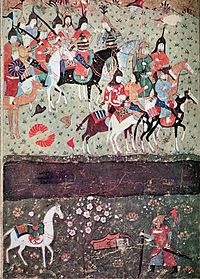

Genghis Khan watches in amazement after Khwarezmi Jalal ad-Din forded the Indus on horseback. | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Mongol Empire | Khwarezmian dynasty | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Genghis Khan Chagatai Khan Ögedei Khan |

Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

50,000 cavalry[2] more than 50,000 men[3]–more than 300,000 men[4] |

3,000 cavalry[2] 30,000–35,000 men (refugees)[3] 700 bodyguards[2] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Heavy More than Khwarezmian casualties and losses | Most of the army | ||||||||

The Battle of the Indus was fought at the Indus River, in 1221 between Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu, the sultan of the Khwarezmian Empire and his remaining forces of 30,000 men against the 200,000 strong Mongolian army of Genghis Khan.

Background[]

Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu was fleeing to India with his men and thousands of refugees from Persia, following the Mongol sacking of several cities, including Bukhara and Samarkand, the latter being the Khwarezmian capital. Jalal al-Din defeated the Mongols in the Battle of Ustuva, the Battle of Kendakhar, the Battle of Waliyan, the Battle of Djerdin and the Battle of Parwan,[5][6] near the city of Ghazni.

According to Ibn Al-Athir's account, after the battle of Parwan, Jalal al-Din sent a message to Genghis Khan, stating "In which locality do you want the battle to be, so that we may make our way to it?" On the evening of the day the battle was won, a quarrel arose among the two main generals of Jalal al-Din, Sayf Al-Din Bugrakh and Malik Khan, and as a result 30,000 soldiers of Sayf Al-Din Bughrakh abandoned Jalal's army.[7] Then came a large army, larger than the one in the battle of Parwan, sent by Genghis Khan under the leadership of his son Tolui[a] and Jalal al-Din met them in Kabul and defeated them again.

As his newly formed army was disassembled after having fought three battles against the Mongols and being abandoned by half of the army, Jalal ad-Din Mingburnu headed for India to seek refuge together with his army of some 3,000 men and several thousand refugees.[2] However, at fırst an advance army of Genghis khan under the leadership of a Mongol general named Chagan caught up with Jalal al-Din at a place named Djerdin. Jalal al-Din defeated them there[8] but a powerful army, which was at least 5 times bigger than the forces of Jalal al-Din, under Genghis Khan, numbering 25,000–50,000 cavalry, caught up with him when he was about to cross the Indus River.[2]

Battle[]

Jalal ad-Din positioned his army of at least 30,000 men (consisted of 3,000 cavalry, 700 bodyguards and refugees of Central Asian Turkomans, Tajiks, Uzbeks, Kangly origin)[1] in a defensive stance against the Mongols, placing one flank against the mountains while his other flank was covered by a river bend.[5] Genghis Khan gave Chagatai Khan command of the right wing; he gave command of the left wing to Ögedei Khan.[9] Jalal ad-Din's army was much weaker.[9][6][b] Khwarezmian army's right wing rested on the river and was being commanded by Malik Khan. Khwarezmian army's left wing was deployed on rising grounds. Jalal ad-Din thus covered his flanks making it difficult for Genghis Khan to outflank his forces.[6]

The initial Mongol charge that opened the battle was beaten back.[5] Jalal ad-Din counterattacked in the centre with his crack 700-man bodyguard[6] and nearly breached the center of the Mongol Army.[5] Genghis then sent a contingent of 10,000 men around the mountain to flank Jalal ad-Din's army.[5] The soldiers of Jalal ad-Din's army, which were 30,000 in total, were much fatigued with having fought ten whole hours against more than 300,000 men, were seized with fear and fled.

Genghis Khan wanted Jalal ad-Din alive and forbade killing him; in order to prevent his escape, Genghis Khan arranged his forces in a form of a bow. With his army being attacked from two directions and collapsing into chaos, Jalal ad-Din, left with 700 men held out in the centre, kept striking out in various directions but was left almost alone and for his own safety, took off his armor, rode his horse into the river and forced it to jump into the river from a low cliff (about 50 feet high), swam on horseback, safely reaching the other bank of the Indus River in spectacular style. Genghis Khan witnessed the feat and famously remarked: "Fortunate should be the father of such a son."[1] Genghis Khan did not allow his men to shoot at Jalal ad-Din. The Mongol warriors wanted to chase Jalal ad-Din but Genghis Khan did not permit them, stating "the prince will defeat all of their attempts." Chagatai Khan was sent back south to hunt down Jalal al-Din who, reports given to Genghis Khan said, had re-crossed the Sindhu to bury his dead.[5][2][9][6]

Ibn Al Athir mentions that the Mongols lost more lives and suffered more wounds than that of Khwarezmians.

Aftermath[]

Chagatai Khan was sent back south to hunt down Jalal al-Din who, according to the reports given to Genghis Khan, had re-crossed the Sindhu. East of the Indus River Jalal al-Din remained at large, and defeated two local forces close to Lahore. He was reportedly able to build up his forces to as many as 10,000 men. After summer of 1222, Genghis Khan sent Dorbei Doqshin and Bala back across the Indus to hunt down the refugee prince. The latter retreated towards Delhi. Dorbei and Bala did not remain for long east of the Indus, and Dorbei returned to Genghis Khan near Samarkand. Genghis Khan was furious that they had failed to hunt down Jalal al-Din, and sent him back to India.

Jalal al-Din re-crossed the Indus back to bury the dead of his campaign, Genghis Khan sent Chagatai Khan back to capture Jalal al-Din before he gets strong enough. Settling in India, Jalal al-Din battled with two local forces close to Lahore and defeated them. Jalal al-Din started to raise new army and was able to assemble an army as high as 10,000 strong. Chagatai Khan failed to deal with Jala al-Din and returned back. After summer of 1222, Genghis Khan appointed Dorbei Doqshin and Bala with huge armies to the expedition of Indian subcontinent to pursue Jalal al-Din. Jalal al-Din moved closer to Delhi. Dorbei Doqshin and Bala left Indian subcontinent and returned to Genghis khan when he was in Samarkand. Genghis khan got angry with them and sent them back again with the same mission. In January 1223, three different Mongol armies coming from Khorasan, Seistan and Ghazni met in Saifrud and together they made an all out assault. After being beaten, the Mongol army gave up and left in March. Later, Dorbei Doqshin was sent with the same mission for the second time. Under Dorbei Doqshin's leadership, the Mongol army took Nandana from one of the lieutenants of Jalal ad-Din, sacked it, then proceeded to besiege the larger Multan. The Mongol army managed to breach the wall but the city was defended successfully by the Khwarezmians. Jalal al-Din himself came to the siege and repelled Dorbei Doqshin back. Dorbei Doqshin decided to retreat due to the climate before the city was captured. The siege was aborted after 42 days (March–April 1224). The Mongols under the leadership of Dorbei returned north via Ghazni. Dorbei Doqshin was sent with the same mission again but after several unsuccessful battles against Jalal al-Din, he joined Jalal al-Din and converted to Islam.[10][11][12][13]

Shikhikhutug, on the other hand, was first sent to Nishapur with Tolun Cherbi, the step-brother of Genghis Khan. After his mission in Nishapur, he was appointed the charge of the captive craftsmen in Ghazni that were to be transported to Mongolia. Then he led the siege of Tulak, the governor of Tulak, Hashabi Nizawar agreed to pay tribute to him. After taking Tulak, Shikhikhutug dealt with the coup d'état that took place in Merv.[14]

After the battle of Indus, Genghis Khan went after Saif al-Din Bughraq, who abandoned Jalal al-Din's army after the battle of Parwan, found them and killed them all.[6]

Legacy[]

Ibn al-Athir mentions the battle of the Indus was "very fierce" and he describes the battle as follows:[15]

All recognized that the battles that had preceded were child's play in comparison with this battle.

Genghis khan acknowledged the bravery and courage of Jalal al-Din and the way he kept his composure in hard situations, not losing his tamper. Seeing Jalal al-Din's bravery, against whom Subutai, Jochi, Jebe, Tolui, Shikhikhutug and others failed in previous battles, Genghis khan said the following:[16]

A father should only have such a son. Whether he escaped from the fiery battlefield and came to the brink of salvation from the whirlwind of destruction, great deeds and great revolts will still come from him!

Juvayni, a Mongol statesman who worked under Mongke khan and accompanied Hulagu khan in several expeditions, narrates the admiration of Jalal al-Din by the Mongols and notes that the Mongols compared Jalal al-Din's fighting to Rostam, the son of Zal.[17]

In 1225 Jalal al-Din was mocked by the Georgian Royal Counsellors for his defeat at this battle. Before the Battle of Garni, Jalal al-Din sent letter to Queen Rusudan asking them to submit to him. The Georgians dismissed the threat and responded with an insulting letter, emphasizing how badly he had been beaten by Genghis Khan.[18]

Notes[]

References[]

- ^ a b c Alexander J. P., Decisive Battles, Strategic Leaders, (Partridge India, 2014), 59.

- ^ a b c d e f Sverdrup, Carl (2010). "Numbers in Mongol Warfare". Journal of Medieval Military History. Boydell Press. 8: 109–17 [p. 113]. ISBN 978-1-84383-596-7.

- ^ a b Trevor N. Dupuy and R. Ernest Dupuy, The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History, (Harper Collins Publishers, 1993), 366.

- ^ Osborne (1759). An Universal History, from the Earliest Account of Time, Volume 4. p. 436.

- ^ a b c d e f A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle, Vol. I, ed. Spencer C. Tucker, (ABC-CLIO, 2010), 273.

- ^ a b c d e f Sverdrup, Carl (2017). The Mongol Conquests The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei. West Midlands: Helion & Company Limited. pp. 29, 163, 168. ISBN 978-1-910777-71-8.

- ^ Al-Athir, Ibn (1231). The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir for the Crusading Period from al-Kamil fi'I-Ta'rikh. Translated by D. S. Richards. Part 3. London and New York. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. P. 229 ISBN 9780754640790

- ^ Sverdrup, Carl (2017). The Mongol Conquests The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei. West Midlands: Helion&Company Limited. P. 163 ISBN 978-1-910777-71-8.

- ^ a b c Osborne (1759). An Universal History, from the Earliest Account of Time, Volume 4. p. 436.

- ^ Jackson, Peter (1990). "JALAL AL-DIN, THE MONGOLS, AND THE KHWARAZMIAN CONQUEST OF PUNJAB AND SIND". British Institute of Persian Studies. 28: 45–54 – via British Institute of Persian studies.

- ^ Sverdrup, Carl (2017). The Mongol Conquests The Military Operations of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei. West Midlands: Helion & Company Limited. pp. 168-196. ISBN 978-1-910777-71-8.

- ^ Boyle, John Andrew (June 1963). "THE MONGOL COMMANDERS IN AFGHANISTAN AND INDIA ACCORDING TO THE ṬABAQĀT-I NĀṢIRĪ OF JŪZJĀNĪ". Islamic Studies. 2 (2): 235–247 – via Islamic Research Institute, International Islamic University, Islamabad.

- ^ Atwood, Christopher (2004). ENCYCLOPEDIA OF MONGOLIA AND THE MONGOL EMPIRE. The United States of America: Facts On File, Inc.

- ^ Boyle, John Andrew (June 1963). "THE MONGOL COMMANDERS IN AFGHANISTAN AND INDIA ACCORDING TO THE ṬABAQĀT-I NĀṢIRĪ OF JŪZJĀNĪ". Islamic Studies. 2, No. 2: 241 – via Islamic Research Institute, International Islamic University, Islamabad

- ^ Al-Athir, Ibn (1231). The Chronicle of Ibn al-Athir for the Crusading Period from al-Kamil fi'I-Ta'rikh. Translated by D. S. Richards. Part 3. London and New York. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. p. 229 ISBN 9780754640790

- ^ Toshmurodova, Sarvinoz Quvondiq qizi (July 2021). "JALOLIDDIN MANGUBERDI IS A GREAT COUNTRY DEFENDER" (PDF). JournalNX- A Multidisciplinary Peer Reviewed Journal. 7. Issue: 7: 47–48 – via NOVATEUR PUBLICATIONS.

- ^ History of the World Conqueror by Ala Ad Din Ata Malik Juvaini, translated by John Andrew Boyle, Harvard University Press 1958, p. 411. Read online on the Internet Archive.

- ^ Mclynn, Frank (2015), Genghis Khan His Conquests, His Empire, His Legacy, Da Capo Press, p. 389, ISBN 978-0-306-82396-1

Coordinates: 24°18′43″N 67°45′49″E / 24.312059°N 67.763672°E

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of the Indus. |

- 1221 in the Mongol Empire

- History of Pakistan

- Battles involving the Mongol Empire

- Battles involving the Khwarazmian dynasty

- Conflicts in 1221

- History of Sindh