BeltLine

| |

| Formation | April 2005 (16 years ago) |

|---|---|

| Legal status | Georgia non-profit |

| Purpose | Urban redevelopment and mobility |

| Location |

|

President and Chief Executive Officer (ABI,) Executive Director (ABP) | Clyde Higgs (ABI) Rob Brawner (ABP) |

Main organ | Atlanta BeltLine Inc. (ABI) and Atlanta BeltLine Partnership (ABP) |

| Website | beltline.org |

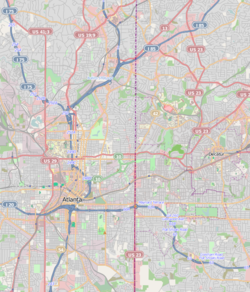

The Atlanta BeltLine (also Beltline or Belt Line) is a former railway corridor around the core of Atlanta, Georgia, under development in stages as a multi-use trail. Some portions are already complete, while others are still in a rough state but hikeable. Using existing rail track easements, the BeltLine is designed to improve transportation, add green space, and promote redevelopment. There are longer-term visions for streetcar or light-rail lines along all or part of the corridor.

The streetcar component of the BeltLine plan was originally developed in 1999 as a master's thesis by Georgia Tech student Ryan Gravel.[1] It links city parks and neighborhoods, but has also been used for temporary art installations. In 2013, the project received a federal grant of $18 million to develop the southwest corridor. In September 2019 the James M. Cox Foundation gave $6 Million to the PATH Foundation which will connect the Silver Comet Trail to The Atlanta Beltline which is expected to be completed by 2022. Upon completion, the total combined interconnected trail distance around Atlanta for The Atlanta BeltLine and Silver Comet Trail will be the longest paved trail surface in the U.S. totaling about 300 Miles (480km).[citation needed]

History and concept[]

Blvd.

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2016) |

As railroad rights-of-way[]

The first development of the BeltLine area began when the Atlanta & West Point Railroad began building a 5-mile (8 km) connecting rail line from its northern terminus at Oakland City to Hulsey Yard on the Georgia Railroad (essentially the southeast quarter of the completed BeltLine). The surveys were done and initial construction had begun when the courts ordered a halt in May 1899 as that work did not fall under the A&WP's charter.[2]

In September 1899, a more ambitious charter for an Atlanta Belt Railway Company was announced that would circle the entire city connecting all rail lines so that freight car transfers could occur on the outskirts rather than downtown. The initial charter was to encompass no more than 30 miles (48 km) and named only perimeter points Howell and Clifton Stations.[citation needed] Since Clifton was in DeKalb County, both it and Fulton were named in the charter. After surveys of the route and right of way acquisitions, the DeKalb portion was ditched leaving the entire route in Fulton County. The entire line was completed by 1902.[citation needed]

Concept for transformation[]

The idea to turn the rail corridors into a ring of trails and parks originated in a 1999 master's degree thesis by Georgia Tech student Ryan Gravel, who founded the non-profit Friends of the Belt Line and works for Perkins+Will. Frustrated with the lack of transportation alternatives in Atlanta, Gravel and two of his colleagues, Mark Arnold and Sarah Edgens, summarized his thesis in 2000 and mailed copies to two dozen influential Atlantans. Cathy Woolard, then the city council representative for district six, was an early supporter of the concept. Woolard, Gravel, Arnold, and Edgens spent the next several months promoting the idea of the BeltLine to neighborhood groups, the PATH foundation, and Atlanta business leaders. Supported by Atlanta mayor Shirley Franklin, previous city council president Cathy Woolard, and many others in Atlanta's large business community, the idea grew rapidly during 2003 and 2004.

The railroad tracks and rights-of-way are owned mostly by CSX Transportation, Norfolk Southern, and the Georgia Department of Transportation. Developer Wayne Mason had purchased most of the NS portion, in anticipation of the BeltLine, but later sold it after conflict with the city.

The total length will be 22 miles (35 km),[3] running about 3 miles (5 km) on either side of Atlanta's elongated central business district. It is planned to include a neighborhood-serving transit system (likely streetcars); footpaths for non-motorized traffic, including bicycling, rollerskating, and walking; and the redevelopment of some 2,544 acres (1,030 ha). The project (although not the funding for it) is included in the 25-year Mobility 2030 plan of the Atlanta Regional Commission for improving transit. As of 2014, the project's planners estimated they had 17 years left before the project would be completed, and no light-rail lines had yet been built.[4]

In 2005 the Atlanta BeltLine Partnership was formed and in 2006 Atlanta BeltLine, Inc. was formed and work began to develop the project.

Connecting the Comet[]

In September 2019 the James M. Cox Foundation gave $6 Million to the PATH Foundation which will connect the Silver Comet Trail to The Atlanta Beltline which is expected to be completed by 2022. Upon completion, the total combined interconnected trail distance around Atlanta for The Atlanta BeltLine and Silver Comet Trail will be the longest paved trail surface in the U.S. totaling about 300 miles (480 km).[citation needed]

Route and trails[]

The BeltLine will feature a continuous path encircling the central part of the city, generally following the old railroad right of way, but departing from it in several areas along the northwest portion of the route. In total, 33 miles (53 km) of multi-use paths are to be built, including spur trails connecting to neighborhoods. The BeltLine connects 45 diverse neighborhoods, some of which are Atlanta's most underserved parks.[5] The PATH Foundation, which has many years of experience building such trails in the Atlanta area, is a partner in the development of this portion of the system.[citation needed]

As of mid-2017, completed trails include:[6]

- Eastside Trail

- Northside Trail

- Southwest Connector Trail

- West End Trail

- Westside Trail

as well as interim hiking trails.

Eastside Trail[]

The Eastside Trail stretches from Piedmont Park in the north to Inman Park and Old Fourth Ward in the south, passing by the greatest concentration of industrial architecture in Atlanta adapted for residential reuse and as offices, retail, dining and shopping, the most notable example being Ponce City Market.

Westside/West End Trail[]

The first trail to be built on the BeltLine, the 2.4-mile West End Trail, was opened in 2008. It edges the neighborhood of the same name as well as serving Mozley Park and Westview. The trail stretches from White Street to Westview Cemetery and is built next to city streets. The Westside Trail, opened in September 2017, is three miles in length and is in the old railroad corridor.[7] The Westside Trail stretches from Washington Park and the MARTA Green (East-West) Line in the north, past West End, ending at University Avenue in Adair Park.[8] Along parts of the Westside Trail, the West End trail runs parallel and just outside of the old rail corridor.

Northside Trail[]

The first section of the Northside Trail opened in 2010 and forms part of a larger network of trails at the south end of Buckhead, the northern third of the city, in and around Tanyard Creek Park in the Collier Hills area. An additional stretch, the Northside Spur Trail was opened 2015.[9]

The trail will eventually connect to the Peachtree Creek Greenway and the PATH400 once complete.[10]

Southwest Connector Trail[]

The Southwest Connector Spur Trail stretches through woods, starting at the Lionel Hampton Trail, ending at Westwood Avenue serving the Beecher Hills and Westwood Terrace neighborhoods. The existing 1.15-mile trail is set to be part of an eventual 4.5-mile trail.[11]

Discontinuities[]

There are five gaps along the BeltLine where rights of way do not connect and thus create larger challenges to the project.

- Armour — Near the Lindbergh Center MARTA station, bisected by two active rail lines. Solving this would involve transit sharing the rail right-of-way and splitting off the trail where Clear Creek joins Peachtree Creek, following Clear Creek around the Armour warehouse properties then tunneling under the active rail lines and I-85 to the Ansley Golf Course then rejoining the BeltLine.

- CSX Hulsey Yard — Near the Inman Park/Reynoldstown MARTA station. A workaround for the trail is to use the existing tunnel at Krog Street.

- Bill Kennedy Way (also known variously as the Glenwood-Memorial Connector and the Glenwood-Wylie Connector) — a bridge spanning I-20 between Glenwood Park/Ormewood Park and Reynoldstown. The proposed fix here is to widen the bridge enough to support trail, transit and motor traffic.

- Washington Park to Joseph E. Boone Boulevard (formerly Simpson Rd) — near the Ashby MARTA station. Proposals include a span over the MARTA tracks or possibly share the right of way.

- Bankhead — The largest gap is near Maddox Park and involves one of the busiest rail corridors in the state. Proposals include 1) taking the trail east to cross under Hollowell Pkwy; 2) diverting through Mead property at Marietta Blvd; or 3) sharing the road with Lowery (formerly Ashby Street).

The Comet Trail Connection[]

In September 2019 the James M. Cox Foundation gave $6 Million to the PATH Foundation which will connect the Silver Comet Trail to The Atlanta Beltline which is expected to be completed by 2022. Upon completion, the total combined interconnected trail distance around Atlanta for The Atlanta BeltLine and Silver Comet Trail will be the longest paved trail surface in the U.S. totaling about 300 Miles (480km).[citation needed]

Parks[]

In 2004, The Trust for Public Land commissioned Alexander Garvin to produce a report, The BeltLine Emerald Necklace: Atlanta's New Public Realm. This report showed the public a vision of transformation for the BeltLine.[12] The BeltLine plan calls for the creation of a series of parks throughout the city creating what the working plan, The Beltline Emerald Necklace,[13] calls the 13 "Beltline Jewels"; they would be connected by the trail and transit components of the plan. In total, the BeltLine will create or rejuvenate 1,300 acres (530 ha) of greenspace. The plan would expand these existing parks:

- Enota Park from 0.3 to 10 acres (0.12 to 4.05 ha)

- Maddox Park from 52 to 114 acres (21 to 46 ha)

- 2 to 8 acres (0.81 to 3.24 ha)

It would also create these new parks:

- 65 acres (26 ha) at Peachtree Creek near Buckhead

- 28 acres (11 ha) at the current McDaniel CEO facility

- 2 acres (0.81 ha)

- Historic Fourth Ward Park (63 acres (25 ha) at the to-be-renovated Ponce City Market (formerly the Sears building and City Hall East)

- 204 acres (83 ha)

- Westside Park 351 acres (142 ha) – roughly twice the size of Piedmont Park – on the site of the former Bellwood Quarry. The 100-foot-deep (30 m) former gravel pit will become a reservoir.[14]

The Trust for Public Land, a national non-profit, partnered with the Atlanta BeltLine project and acquired 33 properties, totaling 1,300 acres. These properties will increase Atlanta's green space by nearly 40%.[15]

Transit[]

The original focus of the BeltLine thesis was on establishing a 22-mile (35 km) light rail loop around the central portion of the city. The vision has expanded to include trails, parks and greenspace, streetscapes, public art, affordable housing, economic development, environmental sustainability, and historic preservation. In Summer 2012, there was a referendum on whether a 1-cent sales tax (SPLOST) should be implemented to fund traffic and road improvements. If approved, the tax would have funded several streetcar routes along portions of the BeltLine trail and connections to MARTA stations and the Downtown Loop streetcar.[16][17][18][19] The sales tax did not pass.[citation needed]

The 2018 MARTA spending plan calls for Atlanta Streetcar tracks to be extended to run on two separate sections of the BeltLine.[20] Northeast and southwestern sections of 2-track light rail will be installed in the right of way under the plan.[21]

Usage issues[]

In late January 2009, GDOT and Amtrak made an unannounced and last-minute filing with the Surface Transportation Board that would effectively block the northeast part of the BeltLine, instead taking it for future intercity rail.[22] However, this conflict was later resolved.[23]

Art[]

"Art on the Atlanta BeltLine" is the city of Atlanta's largest temporary public art exhibition that showcases the work of hundreds of visual artists, performers, and musicians along nine miles (14 km) of the BeltLine corridor. The first exhibition was in 2010.[24] There also is a considerable amount of spontaneous unofficial street art to be found throughout the Beltline ranging from murals to sculptures.

- Examples of BeltLine Art incl. Street Art

Sculptures along the BeltLine

"The Highball Artist" by Hadley Breckenridge on the Lucile Avenue Bridge

Street Art

Street Art

Street Art

Industrial architecture[]

Many former industrial buildings alongside the BeltLine, particularly the Eastside Trail, have been repurposed for residential and retail use, such as Amsterdam Walk, Ponce City Market, Ford Factory Lofts, the Krog Street Market, the Telephone Factory Lofts, and the DuPre Excelsior Mill and the Pencil Factory and N. Highland Steel in Inman Park Village.

Controversy[]

Due to the massive surge in interest in BeltLine adjacent properties and subsequently increased pricing of such properties,[25] many property developers have purchased land in previously low-income neighborhoods and transformed them into luxury living. After having promised to create 5,600 units of affordable housing, the Atlanta BeltLine Inc., has only funded 785, as of July 2017, with overall BeltLine construction halfway completed,[26] with a 2030 estimated finish. For homes within a half-mile of the BeltLine, home values increased between 17.9 and 26.6% between 2011 and 2015.[27] In 2016, project founder Ryan Gravel resigned from the BeltLine Partnership board of directors due to their blatant disregard for affordable housing and departure from his vision.[28] Since Gravel's resignation, there has been several protests to end unregulated gentrification caused by expanding the BeltLine that is displacing Atlantans and diminishing the charm of historic neighborhoods in the city.[29][30][31] In 2017, BeltLine CEO Paul Morris resigned after the Atlanta Journal Constitution exposed his deliberate and complicit disregard for creating and maintaining affordable housing near the Beltline.[32]

References[]

- ^ Can Atlanta Go All In on the BeltLine? by Rebecca Burns May 2014 Atlantic Cities

- ^ Hanson, Robert, The West Point Route, TLC Publishing, 2005, p.22.

- ^ Vasilogambros, Matt (April 21, 2015). "Atlanta's Own High Line May Finally Erase Some Racial Divisions". The Atlantic. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ Sathian, Sanjena (December 31, 2014). "The transit makeover of Atlanta". USA Today. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ "Atlanta Beltline". The Trust for Public Land.

- ^ "Atlanta BeltLine // Where Atlanta Comes Together". beltline.org.

- ^ "West End Trail -". beltline.org.

- ^ "Westside Trail // Atlanta BeltLine". beltline.org.

- ^ "Northside Trail -". beltline.org.

- ^ http://www.reporternewspapers.net/2017/10/28/peachtree-creek-greenway-model-mile-unveiled/ Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ "Southwest Connector Spur Trail -". beltline.org.

- ^ "Atlanta BeltLine Report". The Trust for Public Land.

- ^ Garvin, Alex (December 15, 2004). "The Beltline Emerald Necklace" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 2, 2013. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- ^ Sugg, John F. (January 20, 2011). ""Northwest: Turn a giant hole in the ground into Atlanta's new waterfront", Thomas Wheatley". Creative Loafing Atlanta. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ "Atlanda Beltline". The Trust for Public Land.

- ^ Wheatley, Thomas (February 28, 2011). "Where do you want Beltline transit to go? Here are planners' ideas". Creative Loafing Atlanta. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ Wheatley, Thomas (March 30, 2011). "Streetcar, Beltline, MARTA improvements top Atlanta's transportation-tax wishlist". Creative Loafing Atlanta. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ "Atlanta BeltLine, Inc., "Citywide Briefing on Transit Implementation Strategy & Transportation Investment Act Projects", Feb 17, 2011". Archived from the original on January 3, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on December 16, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Keenan, Sean (October 5, 2018). "After Beltline transit win, More MARTA project list is officially approved". Curbed. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ Keenan, Dean (September 27, 2018). Curbed https://atlanta.curbed.com/2018/9/27/17910242/more-marta-beltline-rail-clifton-corridor-funding. Retrieved December 11, 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ^ Sugg, John F. "Creative Loafing Atlanta". Blogs.creativeloafing.com. Archived from the original on January 7, 2010. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ "39845 – Decision". Stb.dot.gov. Retrieved January 25, 2012.

- ^ "Art on the Atlanta BeltLine". Retrieved April 6, 2013.

- ^ Sears, Sally. "Concern rising over property values following Atlanta Beltline". Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ "How the Atlanta Beltline broke its promise on affordable housing". myajc. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- ^ Immergluck, Dan (2017). "Sustainable for whom? Green urban development, environmental gentrification, and the Atlanta Beltline". Urban Geography. 39:4 (4): 546–562. doi:10.1080/02723638.2017.1360041. S2CID 149027808.

- ^ "Ryan Gravel, father of Beltline, resigns from trail's board of directors". September 27, 2016.

- ^ "Atlanta Beltline demonstrators: 'We pay the tax, now lay the tracks'".

- ^ "Leaders say Atlanta BeltLine must not become part of 'infrastructural racism'". June 5, 2020.

- ^ "Parks, Trails, & Protests: The Future of the Atlanta Beltline".

- ^ "Beltline CEO Paul Morris out after agency's recent troubles on affordable housing".

Further reading[]

- Thomas Wheatley, "How to make the Beltline happen", Creative Loafing, January 20, 2011 – Description of five key BeltLine projects

- Kaid Benfield,The Country's Most Ambitious Smart Growth Project", The Atlantic, July 26, 2011 – Assessment of progress on BeltLine development through July 2011

External links[]

- Rail trails in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Passenger rail transportation in Georgia (U.S. state)

- Hiking trails in Atlanta

- Urban planning in the United States

- Transportation in Atlanta

- Transportation in Fulton County, Georgia

- Proposed railway lines in the United States

- Cycling in Atlanta

- Elevated parks

- Linear parks

- Parks in Atlanta

- Bike paths in Georgia (U.S. state)