Ben Day process

The Ben Day process, named after illustrator and printer Benjamin Henry Day Jr. (son of 19th-century publisher Benjamin Henry Day)[1] is a printing and photoengraving technique dating from 1879.[2] While the Ben Day process is commonly described in terms of dots ("Ben Day dots"), other shapes may be used, such as parallel lines, textures, irregular effects or waved lines.[3]

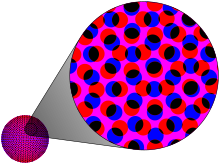

Depending on the effect, colour and optical illusion needed, small colored dots are closely spaced, widely spaced or overlapping.[4] Magenta dots, for example, are widely spaced to create pink. Comic books of the 1950s through the 1970s used Ben-Day dots[5] in the four process colors (cyan, magenta, yellow and black) to inexpensively create shading and secondary colors such as green, purple, orange, and flesh tones on the cheap paper on which they were printed.[6][7]

The Ben-Day dots process differ from the halftone dots process in that the Ben-Day dots are always of equal size and distribution in a specific area. To apply the dots to a drawing the artist would purchase transparent overlay sheets from a stationery supplier. The sheets were available in a wide variety of dot size and distribution, which gave the artist a range of tones to use in the work. The overlay material was cut in the shapes of the tonal areas desired—i.e. shadow or background or surface treatment—and rubbed onto the specific areas of the drawing with a burnisher. When photographically reproduced as a line cut for letterpress printing, the areas of Ben-Day overlay provided tonal shading to the printing plate.[8][9]

The use of Ben-Day dots was a hallmark of American artist Roy Lichtenstein,[2][10] who enlarged and exaggerated them in many of his paintings and sculptures. Other illustrators and graphic designers have used enlarged Ben-Day dots in print media for a similar effect.[citation needed]

See also[]

- Dither

- Halftone

- Letratone

- Pointillism

- Hatching (heraldry), the representation of color by monochrome lines.

- Polka dot

References[]

- ^ G.H.E. Hawkins (1914) "Ben Day Effects", Newspaper Advertising, pp. 17–21, Advertisers Publishing Company, Chicago

- ^ Jump up to: a b Churchwell, Sarah (February 23, 2013). "Roy Lichtenstein: from heresy to visionary". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2012-06-27.

- ^ Edmund F. Russ (Oct 1919) "The Ben Day Process", Western Advertising, Vol. 1 No. 9, pp. 5-&c, Ramsey Oppenheim Co., San Francisco

- ^ W. Livingston Larnard (1921) "How and When to Use Ben Day", The Printing Art Vol. 37, No.4, pp. 305–312 (See also: pp. 30, 216, 218, 347, 463)

- ^ https://4cp.posthaven.com/in-defense-of-dots-the-lost-art-of-comic-book

- ^ "The Use and Abuse of Ben Day" (Jan 6, 1920) Business Digest and Investment Weekly, Vol. 25, No. 1. pp. 10–11, Arrow Publishing Corporation, NY

- ^ Success in Commercial Art (1920) Meyer Both College of Commercial Art

- ^ Gilbert P. Farrar (Sep 18, 1913) "Strong Displays by Use of 'Ben Day' Process", Printer's Ink, Vol. 34, No. 12, pp. 33–36, New York

- ^ Willard C. Brinton (1919) Graphic Methods for Presenting Facts, The Engineering Magazine Company, NY

- ^ Monroe, Robert (September 30, 1997). "A Pioneer of Pop Art movement". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. The Associated Press. Retrieved 2012-06-27.

- Printing processes

- Dot patterns

- Engraving