Berlin movement

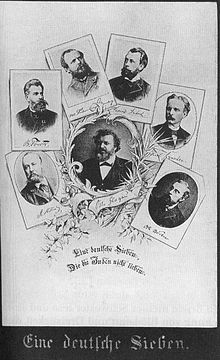

"A German Seven". Montage of portraits showing well-known German antisemites ca. at the time of the "Antisemitenpetition" (1880/1881). Centre: Otto Glagau, around him clockwise: Adolf König, Bernhard Förster, Max Liebermann von Sonnenberg, Theodor Fritsch, Paul Förster and Otto Böckel. Writing says "A German seven / those who do not love the Jews", but can also be read as "A German seven / those who the Jews do not love". Original at Goethe- und Schiller-Archiv Weimar, signature GSA 101/151 (Nietzsche-Archiv Ikonographie, apparently estate of Bernhard Förster via Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche) [2].

Scan of a facsimile in Benders/Oettermann (ed.): Friedrich Nietzsche - Chronik in Bildern und Texten, Hanser / dtv 2000, p. 575 | |

| Formation | 1880s |

|---|---|

| Purpose | Anti-Semitism |

| Location |

|

Key people | Otto Glagau, Adolf Stoecker |

The Berlin movement was an anti-Semitic intellectual and political movement in the German Empire in the 1880s. The movement was a collection of unassociated individuals and organizations.

The movement developed in the aftermath of the Panic of 1873 that led to a recession in the United States and parts of the western European economy. It assailed Jews and capitalism; along with this critique it opposed liberalism and it represented a fear of social democracy. Finally, the movement came out of a racial conception of national identity on the part of the German middle class.

The movement had several leaders. The journalist and author led a journal, Der Kulturkämpfer, [The Culture Warrior] that propagated these ideas. The Lutheran theologian and politician, Adolf Stoecker, led the Christian Social Party. He was the only elected representative of the party in the Reichstag.

The movement lost strength after the CSP's losses in the 1887 elections. Additionally, the Chancellor Otto von Bismarck distanced himself from the party. The significance of the movement laid in its being the first anti-Semitic movement in modern Germany.

See also[]

References[]

- Max Schön: Die Geschichte der Berliner Bewegung. Oberdörffer, Leipzig 1889 * Wanda Kampmann: Adolf Stoecker und die Berliner Bewegung. In: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht Jg. 13 (1962), S. 558-579 (Auch als Sonderdr. 1962)

- Günter Brakelmann, Martin Greschat, Werner Jochmann: Protestantismus und Politik. Werk und Wirkung Adolf Stoeckers. Christians, Hamburg 1982 (Hamburger Beiträge zur Sozial- und Zeitgeschichte, Bd. 17) ISBN 3-7672-0725-7.

- Hans Engelmann: Kirche am Abgrund. Adolf Stoecker und seine antijüdische Bewegung. Selbstverlag Institut Kirche und Judentum, Berlin 1984 (Studien zu jüdischem Volk und christlicher Gemeinde, Bd. 5) ISBN 3-923095-55-4.

- John C. G. Röhl: Kaiser Wilhelm II. und der deutsche Antisemitismus. In: Wolfgang Benz, Werner Bergmann (eds.): Vorurteil und Völkermord. Entwicklungslinien des Antisemitismus. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, Bonn 1997, S. 252-285, ISBN 3-89331-274-9.

Further reading[]

- Levy, Richard S. The Downfall of the Anti-Semitic Political Parties in Imperial Germany (Yale University Press, 1975).

- Levy, Richard S. ed/ Antisemitism: A historical encyclopedia of prejudice and persecution (2 vol Abc-clio, 2005).

- Magnus, Shulamit S. Jewish emancipation in a German city: Cologne, 1798-1871 ( Stanford University Press, 1997).

- Ragins, Sanford. Jewish Responses to Anti-Semitism in Germany, 1870-1914: A Study in the History of Ideas (ISD, 1980.

- Wistrich, Robert S. Socialism and the Jews: The Dilemmas of Assimilation in Germany and Austria-Hungary (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1982).

- Antisemitism in Germany

- 19th century in Berlin

- Politics of the German Empire

- Social movements in Germany

- 1880s in Germany