Bethlehem Steel

| |

| Type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Steel, shipbuilding, mining |

| Founded | 1857 (roots) 1899 (Bethlehem Steel Company, original company) 1904 (Bethlehem Steel Corporation, new company) |

| Defunct | 2003 |

| Fate | Bankruptcy |

| Successor | Cleveland-Cliffs (2020–present) ArcelorMittal (2006–2020) Mittal Steel Company (2005–2006) International Steel Group (2003–2005) |

| Headquarters | Bethlehem, Pennsylvania |

| Subsidiaries | Bethlehem Steel Company and Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation |

The Bethlehem Steel Corporation was an American company that for much of the 20th century was one of the world's largest steel producing and shipbuilding companies.

Its roots trace to an ironmaking company organized in 1857 in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, and later named the Bethlehem Iron Company. In 1899, the owners of the iron company founded the Bethlehem Steel Company. Five years later, the Bethlehem Steel Corporation was created to be the steelmaking company's corporate parent.

Bethlehem Steel existed through the decline of American steel manufacturing during the 1970s until its bankruptcy in 2001 and final dissolution in 2003, when its remaining assets were sold to International Steel Group.

The Bethlehem Steel Corporation's subsidiaries – the Bethlehem Steel Company and the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation – were two of the most powerful symbols of American industrial manufacturing leadership. Their demise is often cited[by whom?] as one of the most prominent examples of the U.S. economy's shift away from industrial manufacturing, its failure to compete with global competition, and management's penchant for short-term profits.[citation needed]

History[]

Roots: the Bethlehem Iron Company[]

Establishment[]

The Saucona Iron Company was established by Augustus Wolle.[1] The Panic of 1857, a national financial crisis, halted further organization of the company and construction of the works. Eventually, the organization was completed, the site moved elsewhere in the Borough of South Bethlehem, and the company's name was changed to the Bethlehem Rolling Mill and Iron Company.[1] On June 14, 1860, the board of directors of the fledgling company elected Alfred Hunt president.[1]

On May 1, 1861, the company's title was changed again, this time to the Bethlehem Iron Company.[1] Construction of the first blast furnace began on July 1, 1861, and it went into operation on January 4, 1863. The first rolling mill was built between the spring of 1861 and the summer of 1863, with the first railroad rails being rolled on September 26. A machine shop, in 1865, and another blast furnace, in 1867, were completed. During its early years, the company produced rails for the rapidly expanding railroads and armor plating for the US Navy.

Growth[]

Although the company continued to prosper during the early 1880s, its share of the rail market began to decline in the face of competition from growing Pittsburgh and Scranton-based firms such as the Carnegie Steel Company and Lackawanna Steel. The nation's decision to rebuild the United States Navy with steam-driven, steel-hulled warships reshaped Bethlehem Iron Company's destiny.

Following the American Civil War, the Navy quickly downsized after the end of hostilities, as national energies were redirected toward settling the West and rebuilding the war-ravaged South. Almost no new ordnance was produced, and new technology was neglected. By 1881, international incidents highlighted the poor condition of the U.S. fleet and the need to rebuild it to protect U.S. trade and prestige.

In 1883, Secretary of the Navy William E. Chandler and Secretary of the Army Robert Todd Lincoln appointed Lt. William Jaques to the Gun Foundry Board. Jaques was sent on several fact-finding tours of European armament makers and on one of these trips he formed business ties with the firm of Joseph Whitworth of Manchester, England. He returned to America as Whitworth's agent and, in 1885, was granted an extended furlough to pursue this personal interest.

Jaques was aware that the U.S. Navy would soon solicit bids for the production of heavy guns and other products such as armor that would be needed to further expand the fleet. Jaques contacted the Bethlehem Iron Company with a proposal to serve as an intermediary between it and the Whitworth Company, so that Bethlehem could erect a heavy-forging plant to produce ordnance. In 1885, John F. Fritz ("Father of the U.S. Steel Industry"), accompanied by Bethlehem Iron Company directors Robert H. Sayre, (President of the Lehigh Valley Railroad), William Thurston, and Joseph Wharton (who had founded the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania in 1881) met with Jaques in Philadelphia. In early 1886, a contract between Bethlehem Iron and the Whitworth Company had been executed.

In spring 1886, Congress passed a naval appropriations bill that authorized the construction of two armored second-class battleships, one protected cruiser, and one first-class torpedo boat, and the complete rebuilding and modernization of two Civil War-era monitors. The two second-class battleships (the USS Texas and the USS Maine) would have both large-caliber guns (12-inch and 10-inch respectively) and heavy armor plating. Bethlehem secured both the forging and armor contracts on June 28, 1887.

Between 1888 and 1892, the Bethlehem Iron Company completed the first U.S. heavy-forging plant. It was designed by John Fritz with the assistance of Russell Davenport, who had entered Bethlehem's employ in 1888. By autumn 1890, Bethlehem Iron was delivering gun forging to the U.S. Navy and was completing facilities to provide armor plating.[2]

During the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, a structure that was designed to make the world marvel received its giant axle from Bethlehem Iron. The world's first Ferris wheel needed enough steel to assemble a 140-foot tower to support an all-steel wheel, altogether making a 264-foot (80 m) structure. The iron made in Bethlehem Steel's blast furnaces was responsible for the world's largest single piece of cast iron that had ever been made up to that time.[3]

In 1898, Frederick Taylor joined Bethlehem Steel as a management consultant in order to solve an expensive machine shop capacity problem. Taylor and Maunsel White, with a team of assistants, applied a series of management principles established by Taylor and that later would be known as scientific management to increase mass production.

The Bethlehem Iron Company was very successful and profitable. The corporate ownership of the Bethlehem Iron Company believed that it could be even more profitable. To accomplish that goal, the corporate ownership of the Bethlehem Iron Company switched to steel production; the steel production became known as a new company called Bethlehem Steel Company.

Bethlehem Steel Company[]

Establishment and involvement with the Bethlehem Iron Company[]

In 1899, the Bethlehem Steel Company was established. This was the first company to carry the name Bethlehem Steel. The Bethlehem Steel Company (also known as Bethlehem Steel Works) was incorporated to take over all liabilities of the Bethlehem Iron Company.[4][5][6] The Bethlehem Iron Company and the Bethlehem Steel Company were separate companies under the same ownership. The Bethlehem Steel Company leased the properties that were owned by the Bethlehem Iron Company.

In 1901, Charles M. Schwab (no relation to the stockbroker Charles R. Schwab), purchased the Bethlehem Steel Company and made Samuel Broadbent Vice President.[7][6] During this time, the company's lease with the Bethlehem Iron Company came to an end (canceled) as the Bethlehem Steel Company gained control of all properties from the Bethlehem Iron Company; the Bethlehem Iron Company ceased operations.[6]

Operating as a subsidiary of the United States Shipbuilding Company[]

Schwab transferred his ownership of the Bethlehem Steel Company to the United States Steel Corporation (U.S. Steel), the company he was president of. This period was brief; Schwab repurchased Bethlehem Steel Company, then sold it to the United States Shipbuilding Company. The United States Shipbuilding Company owned Bethlehem Steel Company only a brief time. The United States Shipbuilding Company was in turmoil; its subsidiaries, including the Bethlehem Steel Company, contributed to the United States Shipbuilding Company's problems. Schwab again became involved with Bethlehem Steel Company, through the parent company, the United States Shipbuilding Company.[7][6]

The United States Shipbuilding Company planned in 1903 to reorganize as the Bethlehem Steel and Shipbuilding Company, this would be the second company to use the name Bethlehem Steel. However, the United States Shipbuilding Company was not reorganized as the Bethlehem Steel and Shipbuilding Company; instead a plan was drawn up for a new company to be formed to replace the United States Shipbuilding Company. The new company would take the "Bethlehem Steel and Shipbuilding Company" name. The plan was carried out in 1904, but the new company did not take the "Bethlehem Steel and Shipbuilding Company" name; instead, it was named Bethlehem Steel Corporation.[7]

Bethlehem Steel Corporation[]

Establishment and early growth[]

The Bethlehem Steel Corporation was formed by Schwab, who had recently resigned from U.S. Steel, and by Joseph Wharton who founded the Wharton School in Philadelphia. Schwab became the first president and first chairman of the board of directors.[citation needed]

After its formation, the Bethlehem Steel Corporation purchased the Bethlehem Steel Company and the remaining subsidiaries from the United States Shipbuilding Company; the Bethlehem Steel Corporation did not purchase the United States Shipbuilding Company.[7][6] The Bethlehem Steel Company became a subsidiary of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation, though the Bethlehem Steel Company also had subsidiaries of its own. Bethlehem Steel Corporation became the second largest steel provider in the United States with the help of its subsidiary Bethlehem Steel Company. Both the Bethlehem Steel Company and the Bethlehem Steel Corporation existed simultaneously after 1904. Bethlehem Steel Company was eventually merged into Bethlehem Steel Corporation in the 1960s.

Bethlehem Steel Corporation installed the gray rolling mill and produced the first wide-flange structural shapes to be made in America. These shapes were partly responsible for ushering in the age of the skyscraper and establishing Bethlehem Steel as the leading supplier of steel to the construction industry.[citation needed]

In the early 1900s Samuel Broadbent led an initiative to diversify the company. The corporation branched out from steel, with iron mines in Cuba and shipyards around the country. In 1913, under Broadbent, it acquired the Fore River Shipbuilding Company of Quincy, Massachusetts, thereby assuming the role of one of the world's major shipbuilders. In 1917, it incorporated its shipbuilding division as Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation, Limited. In 1922, it purchased the Lackawanna Steel Company, which included the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad as well as extensive coal holdings.[8]

1930s and 1940s[]

During World War I and World War II, Bethlehem Steel was a major supplier of armor plate and ordnance to the U.S. armed forces, including armor plate and large-caliber guns for the Navy.

In the 1930s, the company made the steel sections and parts for the Golden Gate Bridge and built for Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF), a new oil refinery in La Plata City, Argentina, which was the tenth-largest in the world. During World War II, as much as 70 percent of airplane cylinder forgings, one-quarter of the armor plate for warships, and one-third of the big cannon forgings for the U.S armed forces were turned out by Bethlehem Steel.[citation needed]

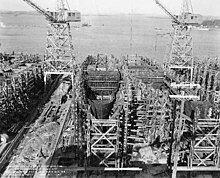

Bethlehem Steel ranked seventh among United States corporations in the value of wartime production contracts.[9] Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation's 15 shipyards produced a total of 1,121 ships, more than any other builder during the war and nearly one-fifth of the U.S. Navy's two-ocean fleet. It employed as many as 180,000 persons, the bulk of the company's total employment of 300,000.

Eugene Grace was president of Bethlehem Steel from 1916 to 1945, and chairman of the board from 1945 until his retirement in 1957. Eugene Grace orchestrated Bethlehem Steel's wartime efforts. In 1943, he promised President Roosevelt one ship per day, and exceeded the commitment by 15 ships.[10]

The war effort drained Bethlehem of much of its male workforce. The company hired female employees to guard and work on the factory floor or in the company offices. After the war, the female workers were promptly fired in favor of their male counterparts.[11]

On Liberty Fleet Day, September 27, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was present at the launching of the first Liberty ship SS Patrick Henry at Bethlehem's Bethlehem Fairfield Shipyard in Baltimore, Maryland. Also launched that same day were the Liberty SS James McKay at Bethlehem Sparrows Point Shipyard, Sparrows Point, Maryland, and the emergency vessel SS Sinclair Superflame at the Fore River Shipyard in Quincy, Massachusetts.

1950s and 1960s[]

When peacetime came, the plant continued to supply a wide variety of structural shapes for the construction trades. Galvanized sheet steel under the name BETHCON was widely produced for use as duct work or .[12]

Additionally, the company produced forged products for defense, power generation, and steel-producing companies.[13]

From 1949 to 1952, Bethlehem Steel had a contract with the federal government of the United States to roll uranium fuel rods for nuclear reactors in Bethlehem Steel's Lackawanna, New York, plant. Workers were not aware of the dangers of the hazardous substance and were not given protective equipment. Some workers have since attempted to receive compensation under a year 2000 radiation-exposure law. The law required the Labor Department to compensate workers up to $150,000 if they developed cancer later in life, if their work history involved enough radiation exposure to significantly increase their cancer risk. The Bethlehem Steel workers have not been awarded this compensation because the radiation dose involved in processing fresh uranium fuel is low, and produces a small risk relative to the baseline risk.[14][15] The larger danger in processing uranium is chemical poisoning from the heavy metal, which does not produce cancer.)[16]

The steel industry in the U.S. prospered during and after World War II, while the steel industries in Germany and Japan lay devastated by Allied bombardment. Bethlehem Steel's high point came in the 1950s, as the company began manufacturing 23 million tons per year. In 1958, the company's president, Arthur B. Homer, was the highest-paid U.S. business executive. The firm built its largest plant, at Burns Harbor, Indiana, between 1962 and 1964.

The late 1960s offered a harbinger of the troubled times to come. In 1967, the company lost its bid to provide the steel for the original World Trade Center. The contracts, a single one of which was for 50,000 tons of steel, went to competitors in Seattle, St. Louis, New York and Illinois.[17]

1970s through 1990s[]

The U.S. advantage lasted about two decades, during which the U.S. steel industry operated with little foreign competition. But eventually, the foreign firms were rebuilt with modern techniques such as continuous casting, while profitable U.S. companies resisted modernization. Bethlehem experimented with continuous casting but never fully adopted the practice.

Meanwhile, the average age of the Bethlehem workforce was increasing, and the ratio of retirees to workers was rising, meaning that the value created by each worker had to cover a greater portion of pension costs than before. Former top manager Eugene Grace had failed to adequately invest in the company's pension plans during the 1950s. When the company was at its peak, the pension payments that should have been made were not. As a result, the company encountered difficulty when it faced rising pension costs and diminishing profits.[18]

By the 1970s, imported foreign steel was generally cheaper than domestically produced steel.[19] The company faced growing competition from mini-mills, smaller-scale operations that could sell steel at lower prices.

In 1982, Bethlehem reported a loss of US$1.5 billion and shut down many of its operations. Profitability returned briefly in 1988, but restructuring and shutdowns continued through the 1990s.[11]

In the mid-1980s, demand for the plant's structural products began to diminish, and new competition entered the marketplace. Lighter construction styles, in part due to lower-height construction styles (i.e., low-rise buildings), did not require the heavy structural grades produced at the Bethlehem plant.

In 1991, Bethlehem Steel Corporation discontinued coal mining (under the name BethEnergy). Bethlehem Steel exited the railroad car business in 1993.

At the end of 1995, it closed steel-making at the main Bethlehem plant. After roughly 140 years of metal production at its Bethlehem, Pennsylvania plant, Bethlehem Steel Corporation ceased its Bethlehem operations.

The Bethlehem Steel Corporation ceased shipbuilding activities in 1997 in an attempt to preserve its steel-making operations. The Bethlehem Steel Corporation would file for bankruptcy in 2001 and dissolve in 2003.

Closing and bankruptcy[]

Despite the closing of its local operations, the Bethlehem Steel Corporation tried to reduce the impact on the Lehigh Valley area with plans to revitalize the south side of Bethlehem. It hired consultants to develop conceptual plans on the reuse of the massive property. The consensus was to rename the 163 acres (66 ha) site Bethlehem Works and to use the land for cultural, recreational, educational, entertainment, and retail development. The National Museum of Industrial History, in association with the Smithsonian Institution and the Bethlehem Commerce Center, consisting of 1,600 acres (650 ha) of prime industrial property, would be erected on the site along with a casino and a large retail and entertainment complex.

Inexpensive steel imports and the failure of management to innovate, embrace technology, and improve labor conditions contributed to Bethlehem Steel's demise.

In 1998, after denied pension benefits, a lawsuit was filed in the 3rd Court of Appeals in Philadelphia: "Lawrence Hollyfield, Fiduciary to the Estate of Collins Hollyfield v. PENSION PLAN OF BETHLEHEM STEEL CORPORATION and Subsidiary Companies;" It was settled in favor of Hollyfield in 2001. It led to a class action lawsuit filed by the workers union soon thereafter. This settlement also led to Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation (PGBC) assuming all pension payouts from Bethlehem Steel, the largest such assumption in U.S. History.[20]

In 2001, the Bethlehem Steel Corporation filed for bankruptcy. In 2003, the company was dissolved and its remaining assets, including the six plants, were acquired by the International Steel Group. International Steel Group was in turn acquired by Mittal Steel in 2005, which then merged with Arcelor to become ArcelorMittal in 2006.

In 2007, the Bethlehem property was sold to Sands BethWorks with plans to build a casino where the plant once stood were drafted. Construction began in fall 2007; the casino was completed in 2009. Ironically, the casino had difficulty finding structural steel for construction due to a global steel shortage and pressure to build Pennsylvania's tax-generating casinos. 16,000 tons of steel were needed to build the $600 million complex.[21]

The site of the company's original plant in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, is home to SteelStacks, an arts and entertainment district. The plant's five blast furnaces were left standing and serve as a backdrop for the new campus. SteelStacks currently features the ArtsQuest Center, a contemporary performing arts center, the Wind Creek Bethlehem casino resort (formerly Sands Casino Resort Bethlehem), a gambling emporium, and new studios for PBS member station WLVT-TV (channel 39).[22] The area also includes three outdoor music venues – , a free music venue featuring lawn seating for up to 2,500 people, Air Products Town Square at Steelstacks, and PNC Plaza, which hosts concerts featuring well-known artists.[23] Levitt Pavilion and the casino resort are connected via the Hoover-Mason Trestle linear park.

In 2012, Bethlehem Steel, a three-piece indie rock band, named itself after the company to honor it.[24]

On November 9, 2016, a warehouse being used as a recycling facility that was part of the Lackawanna, New York, Bethlehem Steel Complex caught fire and burned down.[25]

The corporate records of Bethlehem Steel are housed at the Hagley Museum and Library in Wilmington, Delaware and at the National Museum of Industrial History in Bethlehem.[26]

On May 19, 2019, the former Bethlehem Steel headquarters building in the west side of Bethlehem was imploded.[27]

Shipyards[]

- Fore River Shipyard – Massachusetts

- Bethlehem Sparrows Point Shipyard in Sparrows Point, Maryland

- Alameda Shipyard – California

- Bethlehem Shipbuilding San Pedro in San Pedro, built Destroyers

- Pier 70 in San Francisco – California (formerly "U.S. Iron Works", now BAE Systems San Francisco Ship Repair)

- Mariner Harbor, Staten Island, New York – active for the World War II years and beyond[28]

- *, Beaumont, Texas (1948–1989) The Beaumont Yard was one of the major sources of offshore drilling rigs built in the United States with seventy–two (72) offshore rigs built at the yard.[29] Seventy-one Type C1 ships were built during World War II by Pennsylvania Shipyards, Inc.[30] The shipyard dated back to 1917 owned by the Beaumont Shipbuilding and Drydock Company (1917–1922). Pennsylvania Shipbuilding Company owned and operated the yard from 1922 to 1948. After Bethlehem Steel ownership (1948–1989), the yard was owned by Trinity Industries from 1989 to 1994.

Electric multiple units[]

In 1931/32, Bethlehem Steel manufactured 38 electric multiple unit carriages for the Reading Company.[31]

Freight cars[]

From 1923 to 1991, Bethlehem Steel was one of the world's leading producers of railroad freight cars through their purchase of the former Midvale Steel and Ordnance Company, whose railcar division was at Johnstown, Pennsylvania. Despite its status as a major integrated steel maker, Bethlehem Steel Freight Car Division pioneered the use of aluminum in freight car construction. The Johnstown plant was purchased from Bethlehem Steel through a management buyout in 1991, creating Johnstown America Industries.

Great Lakes Steamship Division[]

This section is empty. You can help by . (August 2021) |

Influence on American landmarks[]

The company manufactured the steel for many of the country's most prominent landmarks:

- Bridges:

- George Washington Bridge

- Golden Gate Bridge

- Peace Bridge

- Verrazano-Narrows Bridge; Staten Island tower.[32]

- Buildings:

- Alcatraz Island

- Empire State Building (Bethlehem supplied some very large structurals only. Building was built by the American Bridge Division of US Steel, using steel manufactured by US Steel.[citation needed])

- World Trade Center (1973–2001)

- Madison Square Garden

- Merchandise Mart

- One Chase Manhattan Plaza 53,000-ton steel frame.[33]

- Rockefeller Center

- Waldorf Astoria

- Dams:

- Railways:

Bethlehem Steel fabricated the largest electric generator shaft in the world, produced for General Electric in the 1950s. It also supplied the steel used for the Wonder Wheel in Coney Island.

- Sports:

- Bethlehem Steel F.C. (1907–1930), sponsored by the Bethlehem Steel corporation, was one of the most successful early American soccer clubs.

- Philadelphia Union II is an American professional soccer team that is the official affiliate of the Philadelphia Union of Major League Soccer. The club was founded and formerly based in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where it was known as Bethlehem Steel FC in honor of the original club.

- In February 2013, the Philadelphia Union of Major League Soccer unveiled a third uniform that honors and harks back to the original Bethlehem Steel F.C.[34][35][36] The kit is primarily black with white trim and features a sublimated Union emblem and a Bethlehem Steel FC jock tag.[37][38]

Gallery[]

1936 specimen stock certificate #0000

Bethlehem Steel Corporation's flagship manufacturing facility in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

"Bethlehem 177" railway gun on display at Museu Militar Conde de Linhares, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

The Burns Harbor, Indiana, plant built by Bethlehem Steel

The Bethlehem Sparrows Point Shipyard at Sparrows Point, Maryland, one of the company's primary steel making and shipbuilding plants

Demolition of part of the original facility in Bethlehem in 2007

Blast furnace A at the flagship plant in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 2009.

The Levitt Pavilion at SteelStacks, the former Bethlehem Steel site, is being prepared for a show.

Former Bethlehem Steel Company Headquarters Building, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, October 2011

Projectile shop in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

Former Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation headquarters in San Francisco

One of the few buildings that have been preserved

See also[]

References[]

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Davis (1877), "Bethlehem Iron Company", History of Northampton County, Pennsylvania, Philadelphia and Reading: Peter Fritts, Chapter XLV, p. 212–213

- ^ Garn, Andrew (1999). Bethlehem Steel. Princeton Architectural Press. p. 14. ISBN 1-56898-197-X.

- ^ Larson, Erik (2003), The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair That Changed America, New York, USA: Crown, ISBN 978-0-609-60844-9, p. 193.CS1 maint: postscript (link)

- ^ Chilton Company, "Iron Age", Volume 63 (1899).

- ^ Henry Varnum Poor, "Poor's Manual of Railroads", Volume 33.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Andrew Garn, "Bethlehem Steel", 1999 Biography (1999).

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Robert T. Swaine, "The Cravath firm and its predecessors, 1819-1947," Volume 1 (1948).

- ^ "Bethlehem Steel to Buy Lackawanna, in $60,000,000 Deal", The New York Times, May 12, 1922.

- ^ Peck, Merton J. & Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School p. 619

- ^ Loomis, Carol J.; Tkaczyk, Christopher (2004-04-05). "The Sinking Of Bethlehem Steel A hundred years ago one of the 500's legendary names was born. Its decline and ultimate death took nearly half that long. A FORTUNE autopsy". CNN Money. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bethlehem Steel, The People Who Built America. YouTube. 5 February 2008.

- ^ Air Conditioning, Heating and Ventilating, Volume 56. Advertisement. Dec. 1959: 111. Google Books. 1959. Retrieved 2017-01-22.

- ^ "Forging America: The History of Bethlehem Steel", The Morning Call, Allentown, Pennsylvania, Morning Call Supplement, 2003. A detailed history of the company by journalists of the Morning Call staff.CS1 maint: postscript (link)

- ^ "Heroes Of The Cold War Out In The Cold". CBS. CBS News. 2006-06-19. Retrieved 2008-01-16.

- ^ "Radiation Exposure for Uranium Industry Workers". Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- ^ "Uranium – U".

- ^ "Contracts Totaling $74,079,000 Awarded for the Trade Center". The New York Times. January 24, 1967.

- ^ Loomis, Carol J.; Tkaczyk, Christopher (2004-04-05). "The Sinking Of Bethlehem Steel A hundred years ago one of the 500's legendary names was born. Its decline and ultimate death took nearly half that long. A FORTUNE autopsy". CNN. Archived from the original on 2014-05-29.

- ^ Henretta, James A.; Edwards, Rebecca; Self, Robert O. (2011). America's History Vol. 2 (Seventh ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 925. ISBN 9780312387921. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ "PBGC to Protect Pensions of 95,000 at Bethlehem Steel - Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation". www.pbgc.gov.

- ^ Assad, Matt (2007-06-27). "BethWorks Says Beam Me Up: Project Officials Scurrying to Get Steel to Bethlehem Steel Site in Time". The Morning Call. redorbit.com. Retrieved 2008-01-18.

- ^ "PBS39". Archived from the original on 2014-11-11. Retrieved 2014-11-15.

- ^ "Artsquest".

- ^ Kohn, Daniel "The Leap from Buffalo to Brooklyn Brought Bethlehem Steel to Their Solid Sound". Village Voice. Retrieved December 15, 2015

- ^ Rosenberg, Eli (2016-11-09). "Fire Engulfs Former Bethlehem Steel Factory in New York". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-11-09.

- ^ "Bethlehem Steel Company records, 1714-1977". Retrieved 2018-10-06.

- ^ Radzievich, Nicole; Sheehan, Jennifer; Sheehan, Daniel Patrick; Wojcik, Sarah M. "Watch implosion of Pennsylvania skyscraper, a landmark of steel industry's glory days". Hartford Courant / The Morning Call. Tribune Publishing. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Three Quarters Of A Century: The George W. Rogers Construction Company, George W. Rogers

- ^ "Drilling Rigs Built in U.S. Shipyards". ShipbuildingHistory.com. Archived from the original on November 10, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ "Bethlehem Steel Company, Beaumont, Texas". Shipbuilding.com. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ^ Commuter cars get new look on the Reading Railway Age April 5, 1965 page 22

- ^ Gay Talese: The Bridge: The Building of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, p.52. Bloomsbury Publishing USA, (2003) ISBN 0802776442

- ^ "NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission" (PDF). nyc.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-06-27.

- ^ ""Jersey Week: Union pay homage to Bethlehem Steel with retro 3rd shirt" at MLS official website, 26 February 2013". Mlssoccer.com. February 26, 2013. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ Lehigh Valley. ""Philadelphia Union honors Bethlehem Steel soccer club on new jerseys", LehighValley.com, 28 February 2013". Lehighvalleylive.com. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ Stephen Barron (July 7, 2012). ""The Philadelphia Union: Following the Ghosts of Bethlehem's Soccer Tradition" by Stephen Barrow, 7 July 2012". Bethlehem.patch.com. Retrieved June 7, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Jonathan Tannenwald, Philly.com. ""Philadelphia Union unveil new third jersey, inspired by Bethlehem Steel", Philly.com, 26 February 2013". Philly.com. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ ""Philadelphia Union Adidas Third Jersey 2013" at TodosobreCamisetas website". Todosobrecamisetas.blogspot.com.ar. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

Bibliography[]

- Hall, P. J. (1915). "History of South Bethlehem, Pa." Semi-centennial, the borough of South Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, 1865–1915. Quinlan Printing Co. pp. 12–13.

Further reading[]

- Warren, Kenneth. Bethlehem Steel: Builder and Arsenal of America. Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2008. ISBN 0-8229-4323-9

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bethlehem Steel. |

- Bethlehem Steel

- Ironworks and steel mills in Pennsylvania

- Companies based in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania

- Industrial buildings and structures in Pennsylvania

- American companies established in 1857

- Manufacturing companies established in 1857

- Manufacturing companies disestablished in 2003

- 1857 establishments in Pennsylvania

- 2003 disestablishments in Pennsylvania

- Former components of the Dow Jones Industrial Average

- ArcelorMittal

- Companies that filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2001

- Sparrows Point, Maryland

- Economic history of Pennsylvania

- Defunct manufacturing companies based in Pennsylvania