Billy Bitzer

Billy Bitzer | |

|---|---|

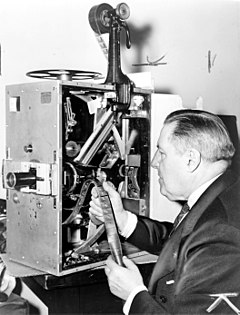

Bitzer, c. 1935 | |

| Born | Johann Gottfried Wilhelm Bitzer[1] April 21, 1872 |

| Died | April 29, 1944 (aged 72) |

| Occupation | Cinematographer |

Gottfried Wilhelm Bitzer (April 21, 1872 – April 29, 1944) was an American cinematographer, notable for his close association and pioneering work with D. W. Griffith.

Biography[]

Prior to his career as a cameraman, working as a motion picture projectionist,[2] Bitzer developed early cinematic technologies for the American Mutoscope Company, eventually to become the Biograph Company.[3] He admired and learned the art of motion picture photography from Kinetoscope inventor W. K. L. Dickson, who directed the early Biograph shorts on which Bitzer cut his teeth. Until 1903, Bitzer was employed by Biograph primarily as a documentary photographer, and from 1903 onward primarily as the photographer of narrative films, as these gained popularity. [4]

In 1908 Bitzer entered into his first collaboration with Griffith. The two would work together for the rest of Bitzer's career, leaving Biograph in 1913 for the Mutual Film Corporation where Bitzer continued to innovate, perfecting existing technologies and inventing new ones. During this time he pioneered the field of matte photography and made use of innovative lighting techniques, closeups, and iris shots.

Bitzer provided assistance during Griffith's directorial debut, 1908's The Adventures of Dollie, which was shot by Arthur Marvin. He eventually succeeded Marvin as Griffith's regular cinematographer, working with him on some of his most important films and contributing significantly to cinematic innovations attributed to Griffith. In 1910, he photographed Griffith's silent short, In Old California, in the Los Angeles village of "Hollywoodland", qualifying Bitzer as, arguably, Hollywood's first Director of Photography. The apex of Bitzer and Griffith's collaboration came with The Birth of a Nation (1915), a film funded in part by Bitzer's life savings, and the epic Intolerance (1916).

His film The Jeffries-Sharkey Fight of 1899 is the first known use of artificial light. Rip Van Winkle (1903) features the first known close-up. Advances in lenses and filters developed by Bitzer made soft focus possible. He was the first to use split-screen photography and backlight, contributing to the development of three-point lighting. He improved in-camera fade and dissolve effects and invented what came to known as transition tools. Even after the Bell & Howell Model 2709 production camera became the industry standard he continued to use a Pathe.[5]

For all his innovation, Bitzer did not survive the industry's transition to sound, and in 1944 he suffered a heart attack and died in Hollywood.

His autobiography, Billy Bitzer: His Story, was published posthumously in 1973.[6]

In 2003, a survey conducted by the International Cinematographers Guild named him one of the ten most influential cinematographers in history.[7] Bitzer, it is said, "developed camera techniques that set the standard for all future motion pictures."[8] Among Bitzer's innovations were the following:

- the fade out to close a movie scene;

- the iris shot where a circle closes to close a scene;

- soft focus photography with the aid of a light diffusion screen;

- filming entirely under artificial lighting rather than outside;

- lighting, closeups and long shots to create mood;

- perfection of matte photography.

Selected filmography[]

- 2 A. M. in the Subway (1905)

- The Kentuckian (1908)

- The Lonely Villa (1909)

- A Sound Sleeper (1909)

- The Sealed Room (1909)

- Edgar Allan Poe (1909)

- A Corner in Wheat (1909)

- In the Border States (1910)

- The Modern Prodigal (1910)

- A Mohawk's Way (1910)

- The Lonedale Operator (1911)

- Enoch Arden (1911)

- The Girl and Her Trust (1912)

- The Female of the Species (1912)

- A Beast at Bay (1912)

- The Root of Evil (1912)

- An Unseen Enemy (1912)

- The Painted Lady (1912)

- The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912)

- The House of Darkness (1913)

- Death's Marathon (1913)

- The Mothering Heart (1913)

- The Yaqui Cur (1913)

- The Battle at Elderbush Gulch (1914)

- Judith of Bethulia (1914)

- The Avenging Conscience (1914)

- The Birth of a Nation (1915)

- Intolerance (1916)

- Hearts of the World (1918)

- The Great Love (1918)

- The Greatest Thing in Life (1918)

- A Romance of Happy Valley (1919)

- The Girl Who Stayed at Home (1919)

- True Heart Susie (1919)

- Scarlet Days (1919)

- Broken Blossoms (1919)

- The Greatest Question (1919)

- The Idol Dancer (1920)

- The Love Flower (1920)

- Way Down East (1920)

- The White Rose (1923)

- America (1924)

- Drums of Love (1927)

- The Battle of the Sexes (1928)

- Lady of the Pavements (1929)

References[]

- ^ Bitzer, G. W.Billy Bitzer: His Story. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1973, p. 183 (Bitzer's full birth name also printed on slipcover of hardback copies of book, which is included at external link of cited copy). Internet Archive, San Francisco, California. Retrieved 1 September 2021. ISBN 0-374-11294-0

- ^ Musser, Charles, The Emergence of Cinema, Publisher: University of California Press; 1st Paperback edition (May 4, 1994) ISBN 978-0520085336

- ^ Hendricks, Gordon (1964), Beginnings of the Biograph, New York, New York: Theodore Gaus' sons

- ^ (Hendricks 1964, pp. 5)

- ^ Crudo, Richard P. (2005). Understanding Digital Cinema: A Professional Handbook. Routledge.

- ^ G. W. Bitzer (as Billy Bitzer). Billy Bitzer: His Story. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1973. ISBN 978-0-374-11294-3

- ^ "Top 10 Most Influential Cinematographers Voted on by Camera Guild," October 16, 2003. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, Micropædia, Vol. II, p51

Further reading[]

- G. W. Bitzer (as Billy Bitzer). Billy Bitzer: His Story. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1973. ISBN 978-0-374-11294-3

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Billy Bitzer. |

- G.W. Bitzer at IMDb

- 1872 births

- 1944 deaths

- American cinematographers

- People from Roxbury, Boston

- American people of German descent