Binary search tree

| Binary search tree | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | tree | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Invented | 1960 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Invented by | P.F. Windley, A.D. Booth, A.J.T. Colin, and T.N. Hibbard | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Time complexity in big O notation | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

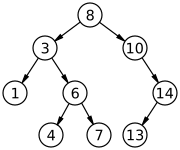

In computer science, a binary search tree (BST), also called an ordered or sorted binary tree, is a rooted binary tree data structure whose internal nodes each store a key greater than all the keys in the node’s left subtree and less than those in its right subtree. A binary tree is a type of data structure for storing data such as numbers in an organized way. Binary search trees allow binary search for fast lookup, addition and removal of data items, and can be used to implement dynamic sets and lookup tables. The order of nodes in a BST means that each comparison skips about half of the remaining tree, so the whole lookup takes time proportional to the binary logarithm of the number of items stored in the tree. This is much better than the linear time required to find items by key in an (unsorted) array, but slower than the corresponding operations on hash tables. Several variants of the binary search tree have been studied.

Definition[]

A binary search tree is a rooted binary tree, whose internal nodes each store a key (and optionally, an associated value), and each has two distinguished sub-trees, commonly denoted left and right. The tree additionally satisfies the binary search property: the key in each node is greater than or equal to any key stored in the left sub-tree, and less than or equal to any key stored in the right sub-tree.[1]: 287 The leaves (final nodes) of the tree contain no key and have no structure to distinguish them from one another.

Often, the information represented by each node is a record rather than a single data element. However, for sequencing purposes, nodes are compared according to their keys rather than any part of their associated records. The major advantage of binary search trees over other data structures is that the related sorting algorithms and search algorithms such as inorder traversal can be very efficient.[note 1]

Binary search trees are a fundamental data structure used to construct more abstract data structures such as sets, multisets, and associative arrays.

- When inserting or searching for an element in a binary search tree, the key of each visited node has to be compared with the key of the element to be inserted or found.

- The shape of the binary search tree depends entirely on the order of insertions and deletions and can become degenerate.

- After a long intermixed sequence of random insertion and deletion, the expected height of the tree approaches square root of the number of keys, √n,[citation needed] which grows much faster than log n.

- There has been a lot of research to prevent degeneration of the tree resulting in worst case time complexity of O(n) (for details see section Types).

Order relation[]

Binary search requires an order relation by which every element (item) can be compared with every other element in the sense of a total preorder. The part of the element which effectively takes place in the comparison is called its key. Whether duplicates, i. e. different elements with the same key, shall be allowed in the tree or not, does not depend on the order relation, but on the underlying set, in other words: on the application only. For a search function supporting and handling duplicates in a tree, see section Searching with duplicates allowed.

In the context of binary search trees, a total preorder is realized most flexibly by means of a three-way comparison subroutine.

Operations[]

Binary search trees support three main operations: lookup (checking whether a key is present), insertion of an element, and deletion of an element. The latter two possibly change the tree, whereas the first one is a navigating and read-only operation. Other read-only operations are traversal, verification etc.

Searching[]

Searching in a binary search tree for a specific key can be programmed recursively or iteratively.

We begin by examining the root node. If the tree is null, the key we are searching for does not exist in the tree. Otherwise, if the key equals that of the root, the search is successful and we return the node. If the key is less than that of the root, we search the left subtree. Similarly, if the key is greater than that of the root, we search the right subtree. This process is repeated until the key is found or the remaining subtree is null. If the searched key is not found after a null subtree is reached, then the key is not present in the tree. This is easily expressed as a recursive algorithm (implemented in Python):

def search_recursively(key, node):

if node is None or key == node.key:

return node

if key < node.key:

return search_recursively(key, node.left)

return search_recursively(key, node.right)

The same algorithm can be implemented iteratively:

def search_iteratively(key, node):

while node is not None and node.key != key:

if key < node.key:

node = node.left

else:

node = node.right

return node

The following interative version of the search function does not use parent pointers in the node data structure, instead it uses a stack for holding the pointers to the ancestors. This stack is embedded into a larger structure, called traverser.[2]: §68

struct TreeNode {

struct TreeNode *child[2];

int key;

int value;

} Node;

#define LEFT 0

#define RIGHT 1

#define left child[LEFT]

#define right child[RIGHT]

#define MAXheight 1024 // BST is possibly unbalanced

struct traverser {

Node* nod1; // current position (NULL,

// if nod1->key ahead or behind all nodes of bst)

int dir; // ∈ {LEFT,FOUND,RIGHT}, i.e.

// == LEFT <==> position at < nod1

// == FOUND <==> position at nod1

// == RIGHT <==> position at > nod1

Node** parent = &ancestors[0]; // -> parent of nod1 or NULL if root

// ancestors[0] == trav->bst->root, if tree not empty.

Node** limit = &ancestors[MAXheight]; // -> utmost entry

BST* bst; // -> BST to which this traverser belongs

Node* ancestors[MAXheight-1];

};

// search Iteratively with Traverser:

int searchIT (struct traverser* trav, int key) {

assert (trav != NULL && trav->bst != NULL);

trav->parent = &(trav->ancestors[-1]);

dir = LEFT; // in case trav->bst (and while-loop) is empty

node = trav->bst->root;

while (node != NULL) {

if (key == node->key) { // key is in the BST

trav->node = node; // onto trav

trav->dir = FOUND;

// 2 == FOUND: key == node->key

return node;

}

if (key < node->key) dir = LEFT;

else dir = RIGHT;

if (++(trav->parent) >= limit) { // stack overflow

fprintf (stderr, "tree too deep\n");

exit (EXIT_FAILURE);

}

*(trav->parent) = node; // onto stack

node = node->child[dir];

}; // end of while-loop

// *(trav->parent) is the node of closest fit

trav->dir = dir;

// 0 == LEFT: key < (*(trav->parent))->key

// 1 == RIGHT: key > (*(trav->parent))->key

return NULL;

}

These three examples do not support duplicates, that is, they consider the tree as totally ordered.

One can note that the recursive algorithm is tail recursive. In a language supporting tail call optimization, the recursive and iterative examples will compile to equivalent programs.

Because in the worst case this algorithm must search from the root of the tree to the leaf farthest from the root, the search operation takes time proportional to the tree’s height (see tree terminology). On average, binary search trees with Nodes keys have O(log |Nodes|) height.[note 2] However, in the worst case, binary search trees can have O(|Nodes|) height, when the unbalanced tree resembles a linked list (degenerate tree).

Searching with duplicates allowed[]

If the order relation is only a total preorder, a reasonable extension of the functionality is the following: also in case of equality search down to the leaves. Thereby allowing to specify (or hard-wire) a direction, where to insert a duplicate, either to the right or left of all duplicates in the tree so far. If the direction is hard-wired, both choices, right and left, support a stack with insert duplicate as push operation and delete as the pop operation.[3]: 155

def search_duplicatesAllowed(key, node):

new_node = node

while new_node != None:

current_node = new_node

if key < current_node.key:

dir = 0 # LEFT

else: # key >= current_node.key:

dir = 1 # RIGHT

new_node = current_node.child[dir]

return (dir, current_node)

A binary tree sort equipped with such a search function becomes stable.

Traversal[]

Once the binary search tree has been created, its elements can be retrieved inorder by recursively traversing the left subtree of the root node, accessing the node itself, then recursively traversing the right subtree of the node, continuing this pattern with each node in the tree as it is recursively accessed. As with all binary trees, one may conduct a pre-order traversal or a post-order traversal, but neither are likely to be useful for binary search trees. An inorder traversal of a binary search tree will always result in a sorted list of node items (numbers, strings or other comparable items).

Code for inorder traversal in Python is given below. It will call callback (some function the programmer wishes to call on the node’s value, such as printing to the screen) for every node in the tree.

def inorder_traversal(node, callback):

if node == None:

return

inorder_traversal(node.leftChild, callback)

callback(node.value)

inorder_traversal(node.rightChild, callback)

Code for (recursive) inorder traversal in C is given below. In this case it will use printf to print the integer value of the node in the screen.

void inorder_traversal(Node *node) {

if (node == NULL) return;

inorder_traversal(node->left);

printf("%i%i ,", node->key, node->value);

inorder_traversal(node->right);

}

Every form of binary tree depth first traversal requires 2×(n−1) ∈ O(n) time, since it visits every arc exactly twice (once down, once up) while visiting every node. This algorithm is also O(n), so it is asymptotically optimal.

Traversal can also be implemented iteratively. For certain applications, e.g. greater equal search, approximative search, an operation for single step (iterative) traversal can be very useful. This is, of course, implemented without the callback construct.

Advancing to the next or previous node[]

This function is useful e.g. in cases where the location of the element being searched for is not known exactly enough. After having looked up a starting point, the search can be continued sequentially.

The node to be started with may have been found in the BST by means of a search function. In the following example, which does not use parent pointers, the stack of pointers to the ancestors has been built e.g. by a searchIT function with successful outcome.

The function inorderNext[2]: §61 returns an inorder-neighbor of the found node, either the inorder-successor (for dir=RIGHT) or the inorder-predecessor (for dir=LEFT), and the updated stack, so that the binary search tree may be sequentially inorder-traversed and searched in the given direction dir further on.

/* Returns the next or previous data item in inorder within the tree being traversed with trav, or if there are no more data items returns NULL.

In the former case inorderNext() may be called again to retrieve the second next item. */

Node* inorderNext (struct traverser* trav, dir) {

assert (trav != NULL);

assert (trav->dir == FOUND);

assert (dir == LEFT || dir == RIGHT);

newnode = trav->node->child[dir];

if (newnode != NULL) {

// Part A: node has a dir-child.

do {

node = newnode;

if (++(trav->parent) > limit) { // stack overflow

fprintf (stderr, "tree too deep\n");

exit (EXIT_FAILURE);

}

*(trav->parent) = node; // onto stack

newnode = node->child[1-dir]

} until (newnode == NULL);

return node;

}

// Part B: node does not have a dir-child.

do {

if (--(trav->parent) < &(trav->ancestors[0])) // stack is empty

return NULL;

oldnode = node;

node = *(trav->parent); // parent of oldnode

} until (oldnode != node->child[dir]);

// now: oldnode == node->child[1-dir], i.e.

// node is ancestor (and predecessor for dir==LEFT resp.

// successor for dir==RIGHT) of the original trav->node.

return node;

}

Note that the function does not use keys, which means that the sequential structure is completely recorded by the binary search tree’s arcs. For traversals without change of direction, the (amortised) average complexity is because a full traversal takes steps for a BST of size 1 step for arc up and 1 for arc down. The worst-case complexity is with as the height of the tree.

The implementation requires stack space proportional to the height of the tree.

Verification[]

Sometimes we already have a binary tree, and we need to determine whether it is a BST. This problem has a simple recursive solution.

The BST property—every node on the right subtree has to be larger than the current node and every node on the left subtree has to be smaller than the current node—is the key to figuring out whether a tree is a BST or not. The greedy algorithm—simply traverse the tree, at every node check whether the node contains a value larger than the value at the left child and smaller than the value on the right child—does not work for all cases. Consider the following tree:

20

/ \

10 30

/ \

5 40

In the tree above, each node meets the condition that the node contains a value larger than its left child and smaller than its right child hold, and yet it is not a BST: the value 5 is on the right subtree of the node containing 20, a violation of the BST property.

Instead of making a decision based solely on the values of a node and its children, we also need information flowing down from the parent as well. In the case of the tree above, if we could remember about the node containing the value 20, we would see that the node with value 5 is violating the BST property contract.

So the condition we need to check at each node is:

- if the node is the left child of its parent, then it must be smaller than (or equal to) the parent and it must pass down the value from its parent to its right subtree to make sure none of the nodes in that subtree is greater than the parent

- if the node is the right child of its parent, then it must be larger than the parent and it must pass down the value from its parent to its left subtree to make sure none of the nodes in that subtree is lesser than the parent.

A recursive solution in C++ can explain this further:

struct TreeNode {

int key;

int value;

struct TreeNode *left;

struct TreeNode *right;

};

bool isBST(struct TreeNode *node, int minKey, int maxKey) {

if (node == NULL) return true;

if (node->key < minKey || node->key > maxKey) return false;

return isBST(node->left, minKey, node->key−1) && isBST(node->right, node->key+1, maxKey);

}

node->key+1 and node->key−1 are done to allow only distinct elements in BST.

If we want the same elements to also be present, then we can use only node->key in both places.

The initial call to this function can be something like this:

if (isBST(root, INT_MIN, INT_MAX)) {

puts("This is a BST.");

} else {

puts("This is NOT a BST!");

}

Essentially we keep creating a valid range (starting from [MIN_VALUE, MAX_VALUE]) and keep shrinking it down for each node as we go down recursively.

As pointed out in section #Traversal, an inorder traversal of a binary search tree returns the nodes sorted. Thus we only need to keep the last visited node while traversing the tree and check whether its key is smaller (or smaller/equal, if duplicates are to be allowed in the tree) compared to the current key.

Insertion[]

Insertion begins as a search would begin; if the key is not equal to that of the root, we search the left or right subtrees as before. Eventually, we will reach an external node and add the new key-value pair (here encoded as a record 'newNode') as its right or left child, depending on the node’s key. In other words, we examine the root and recursively insert the new node to the left subtree if its key is less than that of the root, or the right subtree if its key is greater than or equal to the root.

Here is how a typical binary search tree insertion might be performed in a binary tree in C++:

void insert(Node*& root, int key, int value) {

if (!root)

root = new Node(key, value);

else if (key == root->key)

root->value = value;

else if (key < root->key)

insert(root->left, key, value);

else // key > root->key

insert(root->right, key, value);

}

Alternatively, a non-recursive version might be implemented in C like this. Using a pointer-to-pointer to keep track of where we came from lets the code avoid explicit checking for and handling of the case where it needs to insert a node at the tree root:[4]

void insert(Node** root, int key, int value) {

Node **walk = root;

while (*walk) {

int curkey = (*walk)->key;

if (curkey == key) {

(*walk)->value = value;

return;

}

if (key > curkey)

walk = &(*walk)->right;

else

walk = &(*walk)->left;

}

*walk = new Node(key, value);

}

In the following example, which does not use parent pointers, the stack of pointers to the ancestors has been built e.g. by a searchIT function with outcome key node->key not FOUND.

// insert after search Iteratively with Traverser:

void insertIT(struct traverser* trav,Node* node) {

assert (trav != NULL);

assert (trav->node != NULL);

assert (trav->dir == LEFT || trav->dir == RIGHT);

assert (node != NULL);

trav->node->child[trav->dir] = node;

if (++(trav->parent) > limit) { // stack overflow

fprintf (stderr, "tree too deep\n");

exit (EXIT_FAILURE);

}

*(trav->parent) = node; // onto stack

}

The above destructive procedural variant modifies the tree in place. It uses only constant heap space (and the iterative version uses constant stack space as well), but the prior version of the tree is lost. Alternatively, as in the following Python example, we can reconstruct all ancestors of the inserted node; any reference to the original tree root remains valid, making the tree a persistent data structure:

def binary_tree_insert(node, key, value):

if node == None:

return NodeTree(None, key, value, None)

if key == node.key:

return NodeTree(node.left, key, value, node.right)

if key < node.key:

return NodeTree(binary_tree_insert(node.left, key, value), node.key, node.value, node.right)

return NodeTree(node.left, node.key, node.value, binary_tree_insert(node.right, key, value))

The part that is rebuilt uses O(log n) space in the average case and O(n) in the worst case.

In either version, this operation requires time proportional to the height of the tree in the worst case, which is O(log n) time in the average case over all trees, but O(n) time in the worst case.

Another way to explain insertion is that in order to insert a new node in the tree, its key is first compared with that of the root. If its key is less than the root’s, it is then compared with the key of the root’s left child. If its key is greater, it is compared with the root’s right child. This process continues, until the new node is compared with a leaf node, and then it is added as this node’s right or left child, depending on its key: if the key is less than the leaf’s key, then it is inserted as the leaf’s left child, otherwise as the leaf’s right child.

There are other ways of inserting nodes into a binary tree, but this is the only way of inserting nodes at the leaves and at the same time preserving the BST structure.

Deletion[]

When removing a node from a binary search tree it is mandatory to maintain the inorder sequence of the nodes. There are many possibilities to do this. However, the following method which has been proposed by T. Hibbard in 1962[5] guarantees that the heights of the subject subtrees are changed by at most one. There are three possible cases to consider:

- Deleting a node with no children: simply remove the node from the tree.

- Deleting a node with one child: remove the node and replace it with its child.

- Deleting a node D with two children: choose either D’s inorder predecessor[note 3] or inorder successor[note 4] E (see figure). Instead of deleting D, overwrite its key and value with E’s.[note 5] If E does not have a child, remove E from its previous parent G; if E has a child F, it is a right child, so that it is to replace E at G.

The same method works symmetrically using the inorder predecessor C.

In all cases, when D happens to be the root, make the replacement node root again.

Nodes with two children (case 3) are harder to delete (see figure). A node D’s inorder successor is its right subtree’s leftmost child, say E,[note 4] and a node’s inorder predecessor[note 3] is the left subtree’s rightmost child, C say. In either case, such a node E or C will not have a left resp. right child, so it can be deleted according to one of the two simpler cases 1 or 2 above.

Consistently using the inorder successor or the inorder predecessor for every instance of the two-child case can lead to an unbalanced tree, so some implementations select one or the other at different times.

Runtime analysis: Although this operation does not always traverse the tree down to a leaf, this is always a possibility; thus in the worst case it requires time proportional to the height of the tree. It does not require more, even when the node has two children, since it still follows a single path and does not visit any node twice.

def find_min(self):

"""Get minimum node in a subtree."""

current_node = self

while current_node.left_child:

current_node = current_node.left_child

return current_node

def replace_node_in_parent(self, new_value=None) -> None:

if self.parent:

if self == self.parent.left_child:

self.parent.left_child = new_value

else:

self.parent.right_child = new_value

if new_value:

new_value.parent = self.parent

def binary_tree_delete(self, key) -> None:

if key < self.key:

self.left_child.binary_tree_delete(key)

return

if key > self.key:

self.right_child.binary_tree_delete(key)

return

# Delete the key here

if self.left_child and self.right_child: # If both children are present

successor = self.right_child.find_min()

self.key = successor.key

successor.binary_tree_delete(successor.key)

elif self.left_child: # If the node has only a *left* child

self.replace_node_in_parent(self.left_child)

elif self.right_child: # If the node has only a *right* child

self.replace_node_in_parent(self.right_child)

else:

self.replace_node_in_parent(None) # This node has no children

Parallel algorithms[]

There are also parallel algorithms for binary search trees, including inserting/deleting multiple elements, construction from array, filter with certain predicator, flatten to an array, merging/substracting/intersecting two trees, etc. These algorithms can be implemented using join-based tree algorithms, which can also keep the tree balanced using several balancing schemes (including AVL tree, red–black tree, weight-balanced tree and treap) .

Examples of applications[]

Sort[]

A binary search tree can be used to implement a simple sorting algorithm. Similar to heapsort, we insert all the values we wish to sort into a new ordered data structure—in this case a binary search tree—and then traverse it in order.

The worst-case time of build_binary_tree is O(n2)—if you feed it a sorted list of values, it chains them into a linked list with no left subtrees. For example, build_binary_tree([1, 2, 3, 4, 5]) yields the tree (1 (2 (3 (4 (5))))).

There are several schemes for overcoming this flaw with simple binary trees; the most common is the self-balancing binary search tree. If this same procedure is done using such a tree, the overall worst-case time is O(n log n), which is asymptotically optimal for a comparison sort. In practice, the added overhead in time and space for a tree-based sort (particularly for node allocation) make it inferior to other asymptotically optimal sorts such as heapsort for static list sorting. On the other hand, it is one of the most efficient methods of incremental sorting, adding items to a list over time while keeping the list sorted at all times.

Priority queue operations[]

Binary search trees can serve as priority queues: structures that allow insertion of arbitrary key as well as lookup and deletion of the minimum (or maximum) key. Insertion works as previously explained. Find-min walks the tree, following left pointers as far as it can without hitting a leaf:

// Precondition: T is not a leaf

function find-min(T):

while hasLeft(T):

T ? left(T)

return key(T)

Find-max is analogous: follow right pointers as far as possible. Delete-min (max) can simply look up the minimum (maximum), then delete it. This way, insertion and deletion both take logarithmic time, just as they do in a binary heap, but unlike a binary heap and most other priority queue implementations, a single tree can support all of find-min, find-max, delete-min and delete-max at the same time, making binary search trees suitable as double-ended priority queues.[3]: 156

Types[]

There are many types of binary search trees. AVL trees and red–black trees are both forms of self-balancing binary search trees. A splay tree is a binary search tree that automatically moves frequently accessed elements nearer to the root. In a treap (tree heap), each node also holds a (randomly chosen) priority and the parent node has higher priority than its children. Tango trees are trees optimized for fast searches. T-trees are binary search trees optimized to reduce storage space overhead, widely used for in-memory databases

A degenerate tree is a tree where for each parent node, there is only one associated child node. It is unbalanced and, in the worst case, performance degrades to that of a linked list. If your add node function does not handle re-balancing, then you can easily construct a degenerate tree by feeding it with data that is already sorted. What this means is that in a performance measurement, the tree will essentially behave like a linked list data structure.

Performance comparisons[]

D. A. Heger (2004)[6] presented a performance comparison of binary search trees. Treap was found to have the best average performance, while red–black tree was found to have the smallest number of performance variations.

Optimal binary search trees[]

If a search tree is not intended to be modified, and it is known exactly how often each item will be accessed, it is possible to construct[7] an optimal binary search tree, which is a search tree where the average cost of looking up an item (the expected search cost) is minimized.

Even if we only have estimates of the search costs, such a system can considerably speed up lookups on average. For example, if we have a BST of English words used in a spell checker, we might balance the tree based on word frequency in text corpora, placing words like the near the root and words like agerasia near the leaves. Such a tree might be compared with Huffman trees, which similarly seek to place frequently used items near the root in order to produce a dense information encoding; however, Huffman trees store data elements only in leaves, and these elements need not be ordered.

If the sequence in which the elements in the tree will be accessed is unknown in advance, splay trees can be used which are asymptotically as good as any static search tree we can construct for any particular sequence of lookup operations.

Alphabetic trees are Huffman trees with the additional constraint on order, or, equivalently, search trees with the modification that all elements are stored in the leaves. Faster algorithms exist for optimal alphabetic binary trees (OABTs).

See also[]

- Binary search algorithm

- Search tree

- Self-balancing binary search tree

- AVL tree

- Red–black tree

- Randomized binary search tree

- Tango tree

- Join-based tree algorithms

- Treap

- Weight-balanced tree

Notes[]

- ^ Although the "efficiency" of the search and insert can highly depend on the order in which the elements or keys are inserted since the a unbalanced binary tree, if inserted in a way which forms a singly linked list like structure, has the same (worst-case) complexity as a singly linked list, although not on average where it is logarithmic.

- ^ The notion of an average BST is made precise as follows. Let a random BST be one built using only insertions out of a sequence of unique elements in random order (all permutations equally likely); then the expected height of the tree is O(log |Nodes|). If deletions are allowed as well as insertions, "little is known about the average height of a binary search tree".[1]: 300

- ^ Jump up to: a b Case 1:

If there exists a left sub-tree of a given node A, the inorder predecessor of the node A is the rightmost node (with max key) within A’s left sub-tree.

// If NULL is returned, it indicates that there isn’t any // left sub-tree, hence Case 1 failed. Node *inorder_predecessor(Node *input_node){ Node *temp_node = input_node; if (temp_node->left != NULL) { do { temp_node = temp_node->left; } while(temp_node->left != NULL); } else { return NULL; } return temp_node; }

This approach is essentially the same as

Part Agiven in section #Advancing to the next or previous node withdir == RIGHT.Case 2:

If there does not exist a left sub-tree for a given node A, we’ll traverse the Binary Search Tree from the root until A, and the inorder predecessor of A is the node in which A’s sub-tree exists as its right node i.e. the last or recent parent in which A exists within its right sub-tree.Node *inorder_predecessor(Node *input_node) { // If NULL is returned, there isn’t inorder predecessor // for the given 'input_node' with case 2’s traversal technique. Node *last_right_turn_parent = NULL; Node *temp_node = root_bst; while (temp_node->key != input_node->key) { if (input_node->key > temp_node->key) { last_right_turn_parent = temp_node; temp_node = temp_node->right; } else { temp_node = temp_node->left; } } return last_right_turn_parent; }

This approach satisfies the same functionality as

Part Bin section #Advancing to the next or previous node withdir == RIGHT. But it has two disadvantages:- It requires knowledge of the user data, here: key and comparison function, which is not needed by the mentioned.

- The mentioned has an average complexity of compared to of this approach here in the footnote.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Case 1:

If there exists a right sub-tree for a given node A, the inorder successor of A is the leftmost node (with min key) within the sub-tree of A’s right sub-tree.// If NULL is returned, it indicates that isn’t // any right child for 'input_node, hence case 1 is failed. Node *inorder_successor(Node *input_node){ Node *temp_node = input_node; if (temp_node->right != NULL) { do { temp_node = temp_node->right; } while (temp_node->right != NULL); } else { return NULL; } return temp_node; }

This approach is essentially the same as

Part Agiven in section #Advancing to the next or previous node withdir == LEFT.Case 2:

If there doesn’t exist a right sub-tree for a given node A, to find the inorder successor, we'll have to traverse to A from the root, and the inorder successor of A is the node whose right child is the sub-tree where A exists i.e. the recent or last node where right-path or right-node is chosen during traversal to reach A.Node *inorder_successor(Node *input_node) { Node *temp_node = root_bst; // If NULL is returned, there isn’t any inorder successor // for the given node using case 2’s traversal technique. Node *last_left_turn_parent = NULL; while (temp_node->key != input_node->key) { if (temp_node->key < input_node->key) { last_left_turn_parent = temp_node; temp_node = temp_node->right; } else { temp_node = temp_node->left } } return last_left_turn_parent; }

This approach satisfies the same functionality as

Part Bin section #Advancing to the next or previous node withdir == LEFT. But it has two disadvantages:- It requires knowledge of the user data, here: key and comparison function, which is not needed by the mentioned.

- The mentioned has an average complexity of compared to of this approach here in the footnote.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Of course, a generic software package has to work the other way around: It has to leave the user data completely untouched, has to detach node E from the tree and then to furnish E with all the BST links to and from D – this way having D removed out of the tree.

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2009) [1990]. Introduction to Algorithms (3rd ed.). MIT Press and McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-262-03384-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b

- ^ Jump up to: a b Mehlhorn, Kurt; Sanders, Peter (2008). Algorithms and Data Structures: The Basic Toolbox (PDF). Springer.

- ^ Trubetskoy, Gregory. "Linus on understanding pointers". Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- ^ Robert Sedgewick, Kevin Wayne: Algorithms Fourth Edition. Pearson Education, 2011, ISBN 978-0-321-57351-3, p. 410.

- ^ Heger, Dominique A. (2004), "A Disquisition on The Performance Behavior of Binary Search Tree Data Structures" (PDF), European Journal for the Informatics Professional, 5 (5): 67–75, archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-27, retrieved 2010-10-16

- ^ Gonnet, Gaston. "Optimal Binary Search Trees". Scientific Computation. ETH Zürich. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

Further reading[]

This article incorporates public domain material from the NIST document: Black, Paul E. "Binary Search Tree". Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures.

This article incorporates public domain material from the NIST document: Black, Paul E. "Binary Search Tree". Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures.- Cormen, Thomas H.; Leiserson, Charles E.; Rivest, Ronald L.; Stein, Clifford (2001). "12: Binary search trees, 15.5: Optimal binary search trees". Introduction to Algorithms (2nd ed.). MIT Press & McGraw-Hill. pp. 253–272, 356–363. ISBN 0-262-03293-7.

- Jarc, Duane J. (3 December 2005). "Binary Tree Traversals". Interactive Data Structure Visualizations. University of Maryland. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 30 April 2006.

- Knuth, Donald (1997). "6.2.2: Binary Tree Searching". The Art of Computer Programming. 3: "Sorting and Searching" (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley. pp. 426–458. ISBN 0-201-89685-0.

- Long, Sean. "Binary Search Tree" (PPT). Data Structures and Algorithms Visualization-A PowerPoint Slides Based Approach. SUNY Oneonta.

- Parlante, Nick (2001). "Binary Trees". CS Education Library. Stanford University.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Binary search trees. |

- Ben Pfaff: An Introduction to Binary Search Trees and Balanced Trees. (PDF; 1675 kB) 2004.

- Binary Tree Visualizer (JavaScript animation of various BT-based data structures)

- Binary trees

- Data types

- Search trees