Black Paintings

The Black Paintings (Spanish: Pinturas negras) is the name given to a group of fourteen paintings by Francisco Goya from the later years of his life, likely between 1819 and 1823. They portray intense, haunting themes, reflective of both his fear of insanity and his bleak outlook on humanity. In 1819, at the age of 72, Goya moved into a two-story house outside Madrid that was called Quinta del Sordo (Deaf Man's Villa). Although the house had been named after the previous owner, who was deaf, Goya too was nearly deaf at the time as a result of a fever he had suffered when he was 46. The paintings originally were painted as murals on the walls of the house, later being "hacked off" the walls and attached to canvas by owner Baron Frédéric Émile d'Erlanger.[1] They are now in the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

After the Napoleonic Wars and the internal turmoil of the changing Spanish government, Goya developed an embittered attitude toward mankind. He had a first-hand and acute awareness of panic, terror, fear and hysteria. He had survived two near-fatal illnesses, and grew increasingly anxious and impatient in fear of relapse. The combination of these factors is thought to have led to his production of the Black Paintings. Using oil paints and working directly on the walls of his dining and sitting rooms, Goya created works with dark, disturbing themes. The paintings were not commissioned and were not meant to leave his home. It is likely that the artist never intended the works for public exhibition: "these paintings are as close to being hermetically private as any that have ever been produced in the history of Western art."[2]

Goya did not give titles to the paintings, or if he did, he never revealed them. Most names used for them are designations employed by art historians.[3] Initially, they were catalogued in 1828 by Goya’s friend, Antonio Brugada.[4] The series is made up of fourteen paintings: Atropos (The Fates), Two Old Men, Two Old Ones Eating Soup, Fight with Cudgels, Witches' Sabbath, Men Reading, Judith and Holofernes, A Pilgrimage to San Isidro, Women Laughing, Procession of the Holy Office, The Dog, Saturn Devouring His Son, La Leocadia, and Fantastic Vision.

Images of the Black Paintings[]

(Saturno devorando a su hijo), Saturn Devouring His Son, 1819–1823

(El perro), The Dog, 1819–1823

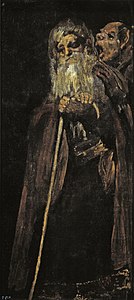

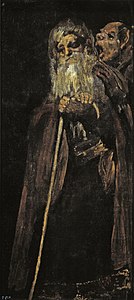

(Dos viejos/Un viejo y un fraile), Two Old Men, 1819–1823

(Hombres leyendo), Men Reading, 1819–1823

(Judith y Holofernes), Judith and Holofernes, 1819–1823

(Mujeres riendo), Women Laughing, 1819–1823

(Una manola/La Leocadia), Leocadia, 1819–1823

Heads in a Landscape (Cabezas en un paisaje, possibly the fifteenth Black Painting)

(Duelo a garrotazos), Fight with Cudgels, 1819–1823

(Dos viejos comiendo sopa), Two Old Men Eating Soup, 1819–1823

(Peregrinación a la fuente de San Isidro/Procesión del Santo Oficio), Procession of the Holy Office, 1819–1823

(El Gran Cabrón/Aquelarre), Witches' Sabbath, 1819–1823

(La romería de San Isidro), A Pilgrimage to San Isidro, 1819–1823

(Vision fantástica/Asmodea), Fantastic Vision, 1819–1823

(Átropos/Las Parcas), Atropos (The Fates), 1819–1823

History[]

Goya acquired the Quinta del Sordo villa on the banks of the River Manzanares, near the Segovia bridge and with views over the plains of San Isidro, in February 1819. It has been suggested that he bought the house to escape public attention; he lived there with Leocadia Weiss, even though she was still married to Isidoro Weiss. It is thought that Goya had a relationship with her and possibly a daughter, Rosario. It is not known exactly when Goya began painting the Black Paintings. He may have started work on the murals between February and November 1819 when he fell seriously ill as testified by the disturbing Self-portrait with Dr Arrieta (1820). What is known is that the murals were painted over rural scenes containing small figures, as Goya made use of the landscapes in some of his murals such as Fight with Cudgels.

If the light-toned bucolic paintings are also the works of Goya, it may be that his illness and the turbulent events of the Trienio Liberal led him to paint over them.[6] Bozal has suggested that those paintings also were painted by Goya as this is the only way to understand why he reused them. However, Nigel Glendinning assumes that the paintings "already adorned the walls of Quinta del Sordo when he bought it."[7] Whatever the truth of the matter, the Black Paintings murals probably date from 1820 and were likely finished no later than 1823 when Goya, departing for Bordeaux, left the villa to his grandson Mariano,[8] perhaps due to fear of reprisals after the fall of Rafael Riego and the republican army. Mariano de Goya transferred ownership of the villa to his father Javier de Goya in 1830.

The slow process of transferring the murals onto canvas began in 1874. The walls of the villa had been covered in wallpaper and Goya had painted on top of this layer which was carefully removed and reapplied to canvas. This work was carried out under the supervision of Salvador Martínez Cubells at the request of Baron Émile d’Erlanger,[9] a French banker of German origins, who wanted to sell them at the Paris World's Fair in 1878. However, in 1881 the baron donated the paintings to the Spanish state and they are now on display at the Museo del Prado.[10]

Original setting[]

Antonio Brugada's inventory mentions seven murals on the ground floor and eight on the top floor. However, only fourteen paintings arrived at the Museo del Prado. Charles Yriarte also describes an additional painting to those currently known to be in the collection; he indicates that when he visited the villa in 1867, it had already been removed from the wall and taken to the Marquis of Salamanca's Vista Alegre Palace. Many critics consider that because of its size and theme the missing painting must be the one identified as Heads in a landscape (New York, collection Stanley Moss).[11]

The other problem regarding the paintings' location revolves around Two Old Men Eating Soup; there is uncertainty whether it was painted on a lintel in the upper or lower floor. Leaving this aside, the original distribution of the murals in Quinta del Sordo was as follows.[12]

The ground floor was a rectangular space. On the two long sides there were two windows near the shorter walls. Between these windows, there were two large murals in the form of landscapes: A Pilgrimage to San Isidro on the right when facing the murals and Witches' Sabbath on the left. At the back, on the smaller wall opposite the entrance, there was a window in the centre with Judith and Holofernes on the right and Saturn Devouring His Son on the left. La Leocadia was located on one side of the door (opposite Saturn) and Two Old Men was opposite Judith.[13]

The first floor was the same size as the ground floor, although there was only one central window in the long walls with a mural on each side. The right-hand wall as one entered contained Fantastic Vision nearest to the entrance with Procession of the Holy Office beyond the window. On the left were Atropos (The Fates) and Fight with Cudgels respectively. On the short wall at the back it was possible to see Women Laughing on the right and Men Reading on the left. To the right of the door was The Dog and to the left Heads in a landscape.

Two Old Men Eating Soup would have been above one of the doors; Glendinning has suggested that it was above the door on the ground floor due to the design of the painted paper that appears in Laurent's photograph of the mural.

(Una manola/La Leocadia), Leocadia, 1819–1823

(El Gran Cabrón/Aquelarre), Witches' Sabbath, 1819–1823

(Saturno devorando a su hijo), Saturn Devouring His Son, 1819–1823

(Judith y Holofernes), Judith and Holofernes, 1819–1823

(La romería de San Isidro), A Pilgrimage to San Isidro, 1819–1823

(Vision fantástica/Asmodea), Fantastic Vision, 1819–1823

(Peregrinación a la fuente de San Isidro/Procesión del Santo Oficio), Procession of the Holy Office, 1819–1823

(Dos viejos/Un viejo y un fraile), Two Old Men, 1819–1823

(Átropos/Las Parcas), Atropos (The Fates), 1819–1823

(Duelo a garrotazos), Fight with Cudgels, 1819–1823

(Hombres leyendo), Men Reading, 1819–1823

(Mujeres riendo), Women Laughing, 1819–1823

(El perro), The Dog, 1819–1823

Heads in a Landscape (Cabezas en un paisaje, possibly the fifteenth Black Painting)

(Dos viejos comiendo sopa), Two Old Men Eating Soup, 1819–1823

Information may be gained from written testimonies regarding the distribution and the original state of the murals and also from an in situ photographic inventory carried out by Jean Laurent in 1874.[14] The photographs were commissioned by Baron d'Erlanger when he employed Martínez Cubells to transfer the paintings. Laurent's photographs were an accurate representation of the process of transferring the murals to canvas. The art historians Gregorio Cruzada Villaamil and Charles Yriarte had been concerned for at least ten years that increases in property prices in the area would result in the redevelopment of the villa and the loss of the paintings.[15]

It is possible to see in Laurent's photographs that the murals were framed with borders painted in classicist design as were the doors, windows and the frieze above the door. The walls were papered as was the custom in bourgeois and aristocratic residences, possibly with wallpaper from the Royal Painted Paper Factory which was patronized by Fernando VII. The paper on the ground floor was decorated with motifs of fruit and leaves and the first floor was decorated with geometrical drawings organized in diagonal lines. The photographs also document the state of the drawings before they were moved, showing, for example, that a large part of the right-hand side of Witches’ Sabbath has not been conserved, although it was transferred to canvas by Martínez Cubells.[16]

Photograph of Witches' Sabbath taken in 1874 by J. Laurent inside Quinta del Sordo |

Witches' Sabbath in its present form with cut edges |

Analysis[]

This section does not cite any sources. (February 2017) |

The chromatic range of the Black Paintings is limited to ochre, gold, brown, grey and black. Only the occasional white shines from clothes to give contrast or the rare stroke of blue from the sky or green from a landscape.

Perhaps the best known of the Black Paintings is Saturn Devouring His Son. The image portrays the Titan Kronos (or Saturn in Roman mythology), father of Zeus, eating one of his children. Fearing a prophecy that one of his children would overthrow him, Saturn ate each of his children upon their birth. Goya depicts this act of cannibalism with startling savagery. The background is black while the limbs and head of Saturn seem to pop out of the shadows. Saturn's eyes are huge and bulging as if he is mad. His fingers dig into the back of his child whose head and right arm are already consumed. Saturn is about to take another bite of the body's left arm. The only use of color beside fleshtones is the splash of red blood covering the mutilated outline of the upper part of the partially eaten, motionless body which is chillingly depicted in deathly white.

Witches' Sabbath or The Great He-Goat (El aquelarre) is an ominous, gloomy and earth-toned illustration which depicts the ancient belief that the Sabbath was a meeting of witches supervised by the Devil who took the form of a goat. The goat is painted entirely in black and appears as a silhouette in front of a coven of witches and warlocks. They have sunken eyes and horrifying features, and appear huddled together, leaning towards the Devil. Only one girl seems resistant to the crowd. She sits at the far right, dressed in black. Though she does not appear involved in the ritual, she does seem to be captivated by the group's relationship to the Devil.

Not all of the Black Paintings share the limited colours of the previous two examples. Fight with Cudgels shows Goya's dramatic use of different shades of blue and red as two men beat each other. While in the original version they were fighting on a meadow, the painting was damaged during the transfer and the version at the Prado has been painted over, stressing the eeriness of the fighters, unable to escape each other's blows due to their knee-deep entrapment in a quagmire. It has been taken as a premonition of the fight of the two Spains that would dominate the following decades. Fantastic Vision also uses bright red in the garb of one of the two giant figures hovering over a group of horsemen and also in the feather of the hat of a rifleman taking aim at these figures.

Art critics agree that certain psychological and social influences lay behind the creation of the Black Paintings. Among the former was the painter's awareness of physical decline, accentuated by his cohabitation with a far younger woman, Leocadia Weiss. Goya's serious illness of 1819 marks the beginning of this decline; it struck him down and left him weak and near to death. These preoccupations are reflected in Goya's use of colors and choice of subjects.

From a sociological point of view, everything suggests that Goya painted these murals after 1820 and after recovering from his illness, although there is no definitive proof of this. His satirical treatment of religion (pilgrimages, processions, the Inquisition) and civil confrontations (such as in Fight with Cudgels, or the visibly conspiratorial meetings that appear in Men Reading; or even taking into account the political interpretation that may be applied to Saturn: the state devouring its subjects or citizens) is concordant with the unstable position that Spain found itself in following the constitutional uprising led by Fernando Riego. In fact, the period when Spain was governed by a liberal government (the Trienio Liberal which lasted from 1820 to 1823) coincided with the creation of the murals. It may be that the themes and tone of the paintings were made possible by the absence of political censure which increased again with the restoration of absolute monarchy.

Themes[]

Despite a number of attempts, no overarching interpretation of the series in its original context has been widely accepted. Glendinning suggests that Goya decorated his villa in accordance with the décor that is found in the palaces of the nobility and homes of the upper middle classes. According to these rules, and taking into consideration that the ground floor was used as a dining room, the theme of the paintings should accord with their surroundings. This means that the paintings should be country scenes (the villa was situated on the banks of the River Manzanares opposite the San Isidro plain) and still life paintings and representations of banquets that allude to the room's function. Although Goya did not explicitly deal with these themes, Saturn Devouring His Son and Two Old Men Eating Soup represent the act of eating, even if in an ironic way using black humour. In addition Judith killed Holofernes after inviting him to a banquet. Other paintings invert the traditional bucolic scene and are related to the nearby hermitage dedicated to the patron saint of Madrid: A Pilgrimage to San Isidro, Procession of the Holy Office and even Leocadia, whose sepulchre could relate to the cemetery near to the hermitage.

On the first floor, Glendinning highlights the contrast between laughter and tears (satire and tragedy) and between earthly elements and those of the air. The first dichotomy is represented by Men Reading with its serious atmosphere, which is opposed by Women Laughing. These are the only two dark paintings in the room and they represent the model against which the other murals are measured, as they are the paintings that first become visible when a person enters the room. In the same way, the mythological scenes of Fantastic Vision and The Fates represent tragedy, while the other paintings such as Procession of the Holy Office provide a glimpse of a satirical scene. As regards the second of the contrasts, there are figures suspended in the air in the two previously mentioned paintings and others buried or seemingly rooted in the ground as in Duel with Cudgels, Holy Office or Dog.

Style[]

The only constant among the paintings are the stylistic elements. The composition of these paintings is innovative. The figures usually appear off-center, with the most obvious example of this being Heads in a Landscape where five heads cluster in the lower right-hand corner of the painting seemingly cut-off or about to leave the frame. This lack of balance demonstrates a very modern compositional style. Other paintings where the figures are to one side include A Pilgrimage to San Isidro where the main group is off center to the left, Procession of the Holy Office where the main group is to the right and even The Dog where empty space occupies the majority of the vertical space, leaving a small area below for the slope and the semi-submerged head. The composition is also lop-sided in The Fates, Fantastic Vision and even the original of Witches’ Sabbath, although the unevenness was lost when the painting was cut after 1875, even though the painting was removed whole.

Many of the scenes depicted in the Black Paintings are nocturnal and with a stark absence of light. This is true of A Pilgrimage to San Isidro, Witches' Sabbath and Pilgrimage of the Holy Office (an afternoon retreating into sunset) where black backgrounds highlight the relationship with the death of the light. All of this generates a feeling of pessimism, of terrible visions, of enigma and unreal space.

People's faces present reflective or ecstatic attitudes. The figures in the latter condition have their eyes open wider and their pupils surrounded by white; their mouths agape, their faces are caricatures, animalistic and grotesque. We are faced with the digestive tract, something disowned by academic norms. Goya shows us the ugly, the terrible; there is no beauty in art, only "pathos" and a certain intention to display all aspects of human life, including those aspects that make us feel uncomfortable. Bozal, not in vain, has called it the secular Sistine Chapel where salvation and beauty have been substituted by lucidity and an awareness of solitude, old age and death.

All these features are a demonstration of the characteristics that are currently considered to be the precursors of pictorial expressionism. This is because Goya's work is coherent, especially in the way that art critics have appreciated it, and because of the impact that it has had on modern painting. It can be said that in this series Goya went further than ever in realizing his revolutionary ideas and innovative approach to pictorial art.

Authenticity[]

Art historian Juan José Junquera has questioned the authenticity of the Black Paintings. In 2003, he came to the conclusion that they could not have been painted during Goya's lifetime.[17][18] According to Junquera, contemporary legal documents describe the Quinta del Sordo as a villa with only one floor, and the second storey was not added until after Goya's death. If the upper floor did not exist during Goya's time, then the Black Paintings (or at least those found on the upper floor) could not have been the work of Goya. He speculates that Goya's son Javier may have created the paintings, and Javier's son Mariano passed them off as the work of Goya for financial gain. Junquera's theory was rejected by Goya scholar Nigel Glendinning.[19][20][21]

Notes[]

- ^ The New York Times, "The Secret of the Black Paintings," 27 July 2003

- ^ Licht, 159

- ^ Licht, 168

- ^ There have been a number of suggestions for the names of these paintings. The earliest came from the inventory of the painter's assets made by Antonio Brugada after Goya's death.Museo del Prado, on-line educational series «Mirar un cuadro»: El aquelarre (in Spanish). Archived September 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "La Quinta de Goya", magazine Descubrir el Arte, nº 201, November 2015, pp. 18–24. ISSN 1578-9047

- ^ Bozal, vol. 2, pp. 248–249.

- ^ Glendinning (1993), p. 116.

- ^ Arnaiz (1996), p. 19.

- ^ Bozal, vol. 2, p. 247.

- ^ Museo Nacional del Prado: Enciclopedia On-Line (in Spanish), retrieved 9 May 2009.

- ^ "Heads in a landscape with commentary in Spanish". Archived from the original on 3 February 2012.

- ^ There are on line virtual reconstructions of the space on: artarchive.com and theartwolf.com

- ^ Fernández, G. "Goya: The Black Paintings". theartwolf.com, August 2006. Retrieved 4 April 2010

- ^ Carlos Teixidor, "Fotografías de Laurent en la Quinta de Goya", in the magazine Descubrir el Arte, nº 154, December 2011, pages 48–54.

- ^ María del Carmen Torrecillas Fernández, «Las pinturas de la Quinta del Sordo fotografiadas por J. Laurent», Boletín del Museo del Prado, volume XIII, number 31, 1992, page 57 onwards.

- ^ ""Los frescos de Goya"', El Globo, Madrid, 26 July 1875. The newspaper outlined the fact that Martínez Cubells had successfully transferred Witches' Sabbath, "a beautiful canvas of more than five metres in length". This proves that Martínez Cubells transferred the whole painting and that it was later cut, possibly so that it would fit into a restricted space in Paris.

- ^ Junquera, Juan José (2003). "Los Goya: de la Quinta a Burdeos y vuelta". Archivo Español de Arte (in Spanish). 76 (304): 353–370. doi:10.3989/aearte.2003.v76.i304.263. ISSN 0004-0428.

- ^ Junquera, Juan José (2005). "La Quinta del Sordo en 1830: respuesta a Nigel Glendinning". Archivo Español de Arte (in Spanish). 78 (309): 83–105. doi:10.3989/aearte.2005.v78.i309.210. ISSN 0004-0428.

- ^ Lubow, Arthur (27 July 2003). "The Secret of the Black Paintings". The New York Times.

- ^ "Obituaries: Professor Nigel Glendinning". The Telegraph. 3 March 2013.

- ^ Glendinning, Nigel (2004). "Las Pinturas Negras de Goya y la Quinta del Sordo. Precisiones sobre las teorías de Juan José Junquera". Archivo Español de Arte (in Spanish). 77 (307): 233–245. doi:10.3989/aearte.2004.v77.i307.229. ISSN 0004-0428.

Bibliography[]

- Arnaiz, José Manuel, Las pinturas negras de Goya, Madrid, Antiqvaria, 1996. ISBN 978-84-86508-45-6

- Benito Oterino, Agustín, La luz en la quinta del sordo: estudio de las formas y cotidianidad, Madrid, Universidad Complutense, 2002. ISBN 84-669-1890-6

- Bozal, Valeriano, Francisco Goya, vida y obra (2 vols.), Madrid, Tf., 2005. ISBN 84-96209-39-3.

- —, "Pinturas negras" de Goya, Tf. Editores, Madrid, Tf., 1997. ISBN 84-89162-75-1

- Ciofalo, John J. "Blackened Myths, Mirrors, and Memories". In: The Self-Portraits of Francisco Goya. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Connell, Evan S. Francisco Goya: A Life. New York: Counterpoint, 2004. ISBN 1-58243-307-0

- Cottom, Daniel. Unhuman Culture. University of Pennsylvania, 2006. ISBN 0-8122-3956-3

- Glendinning, Nigel, "The Strange Translation of Goya's Black Paintings", The Burlington Magazine, CXVII, 868, 1975.

- —, The Interpretation of Goya's Black Paintings, London, Queen Mary College, 1977.

- —, Goya y sus críticos, Madrid, Taurus, 1982.

- —, "Goya's Country House in Madrid. The Quinta del Sordo", Apollo, CXXIII, 288, 1986.

- —, Francisco de Goya, Madrid, Cuadernos de Historia 16 (col. "El arte y sus creadores", nº 30), 1993.

- Hagen, Rose-Marie y Rainer Hagen, Francisco de Goya, Colonia, Taschen, 2003. ISBN 3-8228-2296-5.

- Hughes, Robert. Goya. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2004. ISBN 0-394-58028-1

- Licht, Fred. Goya: The Origins of the Modern Temper in Art. Universe Books, 1979. ISBN 0-87663-294-0

- Stoichita, Victor & Coderch, Anna Maria. Goya: The Last Carnival. London: Reakton books, 1999. ISBN 1-86189-045-1

- Wilson-Bareau, Juliet. Goya's Prints: the Tomás Harris Collection in the British Museum. London: British Museum Publications, 1981. ISBN 0-7141-0789-1

- Yriarte, Charles, Goya, sa vie, son oeuvre, Paris, Henri Plon, 1867.

- Paintings by Francisco Goya

- 1820s paintings