Blade Runner (1985 video game)

| Blade Runner | |

|---|---|

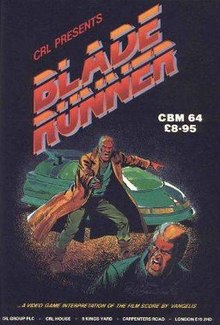

Cover for the Commodore 64 version of the game | |

| Developer(s) | Andy Stodart, Ian Foster |

| Publisher(s) | CRL Group PLC |

| Platform(s) | Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum, Amstrad CPC |

| Release | 1985 |

| Genre(s) | Shoot 'em up |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Blade Runner is a video game loosely inspired by the 1982 film Blade Runner, but is technically based on the film soundtrack by Vangelis as the publishers were unable to obtain a licence for a film tie-in. The game was published in 1985 by CRL Group PLC for Commodore 64, ZX Spectrum and Amstrad CPC. Reviews of the game were mostly negative.

Development and release[]

The game is "inspired by the Vangelis soundtrack" of the 1982 Blade Runner movie. The publisher was unable to obtain rights to the actual movie, so the game was instead said to be based on the soundtrack.[1] The inlay stated that it was a "video game interpretation of the film score".[2]

Plot[]

The plot of the game is similar to the associated movie. Replidroids (sic for replicants), designed for use in space, have been banned from Earth following a revolt on a colony. The role of eliminating any replidroids found on earth is given to a unit of bounty hunters.[3]

Gameplay[]

The game features the player character hunting down replicants for bounty money.[1] On loading the game, the player has to listen to around two minutes of music from the movie soundtrack without any ability to skip the sequence.[3] Author Will Brooker notes that due to the computers' sonic limitations, the "grandiose swoops and fanfares" of the soundtrack were reduced to "a tinny one-channel burble".[4]

The game first presents the player with a map showing the locations of the fugitive replicants and the player's flying car, which must be steered over a droid on the map. At this point the game switches to a side scrolling game in which the player must avoid crowds and cars whilst in pursuit of the replicant.[5] As the levels increase, so does the level of the replicants. The first level replicants are slow and stupid, but the sixth level ones are faster than a human.[6]

Reception[]

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Crash | 58%[7] |

| Sinclair User | 3 out of 5[5] |

| Your Sinclair | 7 out of 10[2] |

| Zzap!64 | 39%[6] |

Sinclair User called the game pretentious[3] and the graphics plodding. The reviewer disliked the lengthy repeating cut scenes, saying that they "are well put together, but after you've seen them more than once you'll get an irresistible urge to smash up your Spectrum".[5] Your Sinclair thought that the game was lacking in variety and did not feel like a finished product.[2] Crash criticized the lack of graphical variety and thought that all the characters looked the same. The reviewer also criticised the sluggishness of the game's controls and that it was too much like a cut-down version of the hit 1984 game Ghostbusters.[7] Reviewing the game on the Commodore 64, Zzap!64 panned the high difficulty level of the game and described the graphics as bland.[6] Commodore User also thought the graphics were poor and the game disappointing, although they did praise the "excellent" music. They thought it would have been ok as a budget title, but was not worth the full price.[8]

Barry Atkins of the University of Wales's School of Film, Photography and Digital Media describes the game as lazily executed and unsatisfying, "yok[ing] unoriginal gameplay mechanics to glancing visual references to the originating film". In his view, the game was merely an effort to cash in on the film's intellectual property, reducing "all the subtleties, complexities and ambiguities of the film ... to a game that players in the 1980s would have immediately recognised as a fairly mundane example of the 'shoot 'em up' genre, where slogans such as 'Move Off World' painted across a primary coloured and flat game space gesture only vaguely to the film as the player adopts the role of a bounty hunter in a raincoat who bears a crude likeness to Deckard".[9]

References[]

- ^ a b "On the tail of replidroids in CRL's Blade Runner". Crash. Newsfield Publications Ltd (26): 14. March 1986. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ a b c "Screen Shots: Blade Runner". Your Sinclair. Dennis Publishing (3): 28. May 1986. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ a b c "Blade Runner". Sinclair User. EMAP (48): 54. March 1986. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ Brooker, Will (1999). "Internet fandom and the continuing narratives of Star Wars, Blade Runner and Alien". In Kuhn, Annette (ed.). Alien Zone II: the spaces of science-fiction cinema. Verso. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-85984-259-1.

- ^ a b c "Blade Runner". Sinclair User. EMAP (48): 55. March 1986. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ a b c "Blade Runner". Zzap!64. Newsfield Publications (12): 64. February 1986. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ a b "Reviews – Blade Runner". Crash. Newsfield Publications Ltd (27): 128. April 1986. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ "Commodore User Magazine Issue 29". February 1986.

- ^ Atkins, Barry (2005). "Replicating the Blade Runner". In Brooker, Will (ed.). The Blade Runner Experience: the legacy of a science fiction classic. Wallflower Press. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-1-904764-30-4.

External links[]

- Blade Runner at MobyGames

- Blade Runner at SpectrumComputing.co.uk

- 1985 video games

- Amstrad CPC games

- Blade Runner (franchise)

- Adaptations of works by Philip K. Dick

- Commodore 64 games

- Detective video games

- Video games set in Los Angeles

- Works based on music

- ZX Spectrum games

- Video games developed in the United Kingdom

- Video games with oblique graphics