Blood Feast

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2017) |

| Blood Feast | |

|---|---|

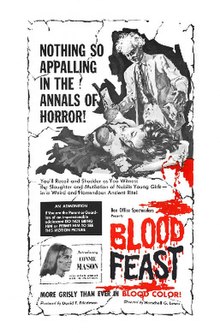

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Herschell Gordon Lewis |

| Screenplay by | Allison Louise Downe |

| Story by | David F. Friedman Herschell Gordon Lewis |

| Produced by | David F. Friedman |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Herschell Gordon Lewis |

| Edited by | Robert Sinise Frank Romolo |

| Music by | Herschell Gordon Lewis |

| Distributed by | Box Office Spectaculars |

Release date |

|

Running time | 67 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $24,500 |

| Box office | $4 million |

Blood Feast is a 1963 American splatter film. It was composed, shot and directed by Herschell Gordon Lewis, written by Allison Louise Downe from an idea by Lewis and David F. Freidman, and stars Mal Arnold, William Kerwin, Connie Mason, and Lyn Bolton. The plot focuses on a psychopathic food caterer named Fuad Ramses (Arnold) who kills women so that he can include their body parts in his meals and perform sacrifices to his "Egyptian goddess" Ishtar.

Blood Feast is considered the first splatter film, a sub-genre of horror noted for its graphic depictions of on-screen gore. It was highly successful, grossing $4 million against its minuscule $24,500 budget, while receiving poor reviews from critics, who criticized it as amateurish and vulgar. The film was followed by a belated sequel, Blood Feast 2: All U Can Eat, in 2002.

Plot[]

In the midst of a series of gruesome murders, a young woman is killed inside her suburban Miami house by a grey-haired, wild-eyed man. He stabs her in the eye and hacks her leg off with a machete, bagging the leg before he leaves. At the police station the next day, detective Pete Thornton investigates the killing, noting that it is the latest in a series of four murders by a homicidal maniac who has yet to leave any clues. The police chief advises him to continue to pursue the case.

At Fuad Ramses Catering store, wealthy socialite Dorothy Fremont arrives, where she arranges for Fuad to cater a party for her daughter Suzette. Fuad agrees and tells Mrs. Fremont that the Egyptian feast that he is preparing has not been served for over 5,000 years. Mrs. Fremont wants the catering done in two weeks, and Fuad assures her that he will have enough time to procure the last of his needed ingredients. After Mrs. Fremont leaves, Fuad ventures to the back storage room where he has displayed a large gold statue of his "Egyptian goddess" Ishtar. Fuad is preparing a "blood feast" – a huge vat containing the dead women's body parts – that will ensure the goddess's resurrection. That evening, teenagers Tony and Marcy make out on a nearby beach. Fuad attacks them, subduing Tony and slicing off the top of Marcy's head. He removes her brain to serve as the latest ingredient. Thornton arrives on the scene with the police chief. After failing to obtain any useful information from the distraught Tony, they interrogate Marcy's mother, who can only tell Pete that her daughter belonged to a book club.

Staking out a local motel, Fuad sees a drunken sailor drop his wife off at her room. Fuad knocks on the woman's door and attacks her when she opens it. Fuad rips the woman's tongue out through her throat as another ingredient to his "blood feast". Pete continues to investigate this latest killing, and discovers that the latest murder victim also belonged to a book club.

Pete attends his weekly Egyptian studies lecture at the local university with his girlfriend, who happens to be Suzette. The lecturer tells them about the cult of Ishtar, and describes how virginal women were sacrificed to the goddess on an altar as a blood offering to the Egyptian goddess. When the lecture is over, Pete takes Suzette out for an evening drive. She becomes worried about the recent attacks and fears that a serial killer is loose in the area. Their date is interrupted by the car radio announcing that another victim has been found near death. Pete drops Suzette home and races to the hospital. The police chief informs him that the maniac has struck again and hacked off the face of another woman named Janet Blake. Pete questions Janet in her hospital bed. Her face bandaged, Janet tells the detectives that the man who attacked her was old, with wild eyes, and that he said something which sounded like "Etar". Janet then dies and Pete cannot shake the feeling that this word sounds familiar. Fuad receives a letter from Trudy requesting a copy of the book Ancient Weird Religious Rites, written by Fuad Ramses. Fuad calls Trudy's home phone number and learns that she's staying with Suzette. That afternoon, Fuad stakes out the Fremont residence, kidnaps Trudy from the grounds and takes her to his store. He whips her savagely and collects her blood, the final ingredient in his bloody potion.

With Trudy missing, Mrs. Fremont insists that the party continue. Pete calls Suzette to inform her that he will be late. Meanwhile, Fuad arrives with the food that he has cooked at his store. Elsewhere, Pete calls upon the college lecturer and gets more information about the cult of Ishtar and Fuad's book. He deduces that Fuad is the killer, since all the victims were women who personally called upon him to send them copies of his book. Pete and the police race over to Fuad's store and find Trudy's chopped-up body in the back. Pete tries to call Suzette to warn her, but Fuad cuts the phone line to the Fremont house.

At the Fremont party, Fuad's meal is ready, but he first asks Suzette to come into the kitchen to help him. He has Suzette lie on a counter, which he makes his altar, and says a prayer to Ishtar as he prepares to decapitate her with his machete as a final offering to his goddess. Dorothy Fremont interrupts Fuad just as he is about to decapitate Suzette, and Fuad escapes as the police arrive. Pete and the rest of the police chase Fuad through a nearby garbage dump, where he attempts to escape by climbing into the back of a departing garbage truck. The truck's compact blades turn on and Fuad is crushed to death. The police stop the truck, noting that there's not much left of Fuad. As Pete puts it, "He died a fitting end, just like the garbage he was."

Cast[]

- William Kerwin as Detective Pete Thornton

- Mal Arnold as Fuad Ramses

- Connie Mason as Suzette Fremont

- Scott H. Hall as Frank, police captain

- Lyn Bolton as Mrs. Dorothy Fremont

- Toni Calvert as Trudy Sanders

- Ashlyn Martin as Marcy, girl on beach

- Sandra Sinclair as Pat Tracey

- Astrid Olson as motel victim

- Herschell Gordon Lewis as radio announcer (uncredited)

Production[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (February 2019) |

Development[]

The concept for Blood Feast arose in the early 1960s, three years after the release of director Alfred Hitchcock’s horror film Psycho. Lewis, previously a teacher at Mississippi State College, had quit his job in order to enter the film business, and directed several “nudie cutie” films in the early 1960s, produced by David F. Friedman (who would later produce Blood Feast and several other splatter films that Lewis would direct). Lewis had seen Psycho and felt that the film had cheated by showing the results of the murders in the film but not the action, because Hitchcock could not risk getting turned down by theaters. The main idea behind Blood Feast was that bathtubs of blood would be spilled in an effort to portray an Egyptian meal cooked with the bodies of virgins and the tongue of a woman being ripped out of a woman’s mouth.[1]

Filming[]

Filming took place in Miami, Florida over a period of four days, with a budget of $24,000.[1] Director Lewis wanted a realistic prop for the scene where a woman gets her tongue ripped out; in order to accommodate this, a sheep’s tongue was imported from Tampa Bay and used in the scene. All other limbs and organs used during production were imported locally. Lewis filmed Blood Feast in color in order to show the red blood used in the film.[1]

Release[]

Distributed by Box Office Spectaculars, the film was released July 6, 1963 at the Bellevue Drive-In in Bellevue (now Peoria) Illinois.[2][failed verification] The film was advertised as Egyptian Blood Feast at drive-ins in New York.[3][unreliable source?]

Producer Friedman came up with some publicity stunts for the film, such as giving theater-goers "vomit bags" and intentionally taking out an injunction against the film in Sarasota, Florida, in order to gain publicity. Both were very effective and generated more interest in the film,[3][unreliable source?] which became highly successful, grossing $4 million against its minuscule $24,500 budget.[4]

In the United Kingdom, the film faced censorship issues, eventually being banned and added to the infamous "video nasty" list.[5] It was given a DVD release in 2001 with 23 seconds of cuts. In 2005, the film was finally released uncut after more than 40 years of being banned.[6][7]

Home media[]

Blood Feast was first released on VHS home video by Continental Video in the 1980s. It also received VHS and DVD releases by Something Weird Video in the late 1990s.[citation needed]

In 2017, Arrow Video released the film in a DVD and Blu-ray double pack.[8]

Significance[]

Blood Feast immediately became notorious for its explicit gore and violence. It is often cited erroneously as one of the first films to show people dying with their eyes open (earlier examples include D. W. Griffith's 1909 film The Country Doctor, William A. Wellman's 1931 film The Public Enemy and 1960's Psycho).[9]

Fuad Ramses was described by author Christopher Wayne Curry – in his book A Taste of Blood: The Films of Herschell Gordon Lewis – as "the original machete-wielding madman" and the forerunner to similar characters in Friday the 13th and Halloween. Lewis said of the film, "I've often referred to Blood Feast as a Walt Whitman poem. It's no good, but it was the first of its type."[10] "One of the all-time greats," enthused Cramps singer and horror aficionado Lux Interior. "It was the first gore movie… Now, it looks kind of funny, but it's still really sick."[11]

Blood Feast is the first part of what the director's fans call "The Blood Trilogy". Rounding out the trilogy are Two Thousand Maniacs! (1964) and Color Me Blood Red (1965). After the third, producer Friedman said, "I think that for now we're going to abandon making any more 'super blood and gore' movies, since so many of our contemporaries are launching similar productions, causing a risk that the market will quickly reach a saturation point."[12]

Critical reception[]

Blood Feast received generally negative reviews. Variety declared the film to be a "totally inept shocker", "incredibly crude and unprofessional from start to finish" and "an insult even to the most puerile and salacious of audiences".[13] The review labeled the entire production a "fiasco", calling the screenplay (credited to Louise Downe) "senseless", and the acting "amateurish". Of Lewis' direction, camerawork, and musical composition, the review judged that he had "failed dismally on all three counts".[13] The Los Angeles Times described Blood Feast as "a blot on the American film industry."[14] Stephen King has said that it is "the worst horror movie" he has ever seen[15]

In response to Variety's criticism of the film, Friedman said, "Herschell and I have often wondered who told the Variety scribe we were taking ourselves seriously".[16]

Jerry Renshaw of Austin Chronicle liked the film, but criticized the film's poor acting and noticeably low budget. Renshaw concluded his review by calling the film "offensive, nasty, shabby, and revolting, but also great fun, if you can stand the sight of guts".[17] On his website Fantastic Movie Musings and Ramblings, Dave Sindelar panned the film, criticizing the acting and stating that director Lewis "manages to make his movies look like home movies without giving them that air of verisimilitude that would make them believable".[18] Dennis Schwartz of Ozus' World Movie Reviews gave Blood Feast a C grade, stating that it was "one of those really bad films that some take pleasure laughing at and others sneering at and others doing both".[19] Allmovie's Fred Beldin wrote, "The plot is threadbare, the acting is on a par with the clumsiest of high school plays and the direction is static and uninvolving. Nevertheless, this is one of the important releases in film history, ushering in a new acceptance of explicit violence that was obviously just waiting to be exploited".[20]

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 42% based on 13 reviews, with a weighted average rating of 4.48/10.[21]

Literature[]

Lewis wrote a novelization of Blood Feast to coincide with the release of the film.[22] The novel, which features significantly different versions of central characters Fuad Ramses, Pete Thornton and Suzette Fremont, has a much more humorous tone than the film and is set in Chicago rather than Miami. It was reprinted by FantaCo Enterprises in the 1980s.[citation needed]

A black-and-white two-issue comic book adaptation of the film was published by Eternity Comics in 1991. It was written by Jack Herman, penciled by Stan Timmons and inked by Mike Matthew.[23]

Legacy[]

Sequels[]

Blood Feast was the first part of Lewis' "Blood Trilogy", with the others being Two Thousand Maniacs! and Color Me Blood Red.[24]

A sequel, Blood Feast 2: All U Can Eat, was released in 2002. It takes place years after the first film, with Fuad's grandson following in his grandfather's footsteps. It marked the first time Lewis and Friedman had worked together on a film in 36 years.[25]

Blood Diner (1987) was produced with the intention of making it a "spiritual sequel" to Blood Feast.[26]

Remake[]

A remake directed by Marcel Walz and starring Robert Rusler as Fuad Ramses, was given a limited theatrical release on June 23, 2017.[27][28][29]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Zinoman, Jason (2011). The Problem with Psycho. New York: Penguin Press. pp. 33–34.

- ^ "BLOOD FEAST (18)". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Blood Feast (1963) – Trivia". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ "Blood Feast (1963) - Financial Information". The Numbers. Retrieved March 29, 2018.

- ^ "Breaking Down All 72 Video Nasties!". Bloody Disgusting. January 29, 2018. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- ^ "Blood Feast". MovieCensorship.com. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- ^ "BLOOD FEAST (18)". British Board of Film Classification. April 18, 2005. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- ^ "Blood Feast Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- ^ Palmer 2000, p. 41.

- ^ Palmer 2000, p. 7.

- ^ Mörat (September 20, 1997). "Splattermania!". Kerrang!. p. 54.

- ^ Romer 2000, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Variety's Film Reviews 1964-1967. 11. R. R. Bowker. 1983. There are no page numbers in this book. This entry is found under the header "May 6, 1964". ISBN 0-8352-2790-1.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (May 2, 1964). "'Blood Feast' Grisly, Boring Movie Trash". Los Angeles Times – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "https://twitter.com/stephenking/status/1409978287661719556". Twitter. Retrieved June 29, 2021. External link in

|title=(help) - ^ Weber, Bruce (February 15, 2011). "David F. Friedman, Horror Film Pioneer, Dies at 87". nytimes.com. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- ^ Renshaw, Jeremy. "Blood Feast . Austin Chronicle . 07-27-98". FilmVault.com. Jeremy Renshaw. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- ^ Sindelar, Dave (May 25, 2015). "Blood Feast (1963)". FantasticMovieMusings.com. Dave Sindelar. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- ^ Schwartz, Dennis. "bloodfeast". Sover.net. Dennis Schwartz. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- ^ Beldin, Fred. "Blood Feast – Review". Allmovie. Retrieved July 2, 2012.

- ^ "Blood Feast (1963) - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes.com. Fandango Media. Retrieved December 29, 2020.

- ^ Lewis, Herschell Gordon (1991). Amazon.com: Blood Feast (9780944736824): Herschell G. Lewis: Books. ISBN 0944735827.

- ^ Frank Plowright (2003). The Slings & Arrows Comic Guide. Top Shelf Productions. p. 86. ISBN 9780954458904.

- ^ "Review: Herschell Gordon Lewis's the Blood Trilogy on Image Entertainment Blu-ray".

- ^ "Blood Feast 2: All U Can Eat (2002) - Herschell Gordon Lewis | Review | AllMovie".

- ^ "Blood Diner". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 12, 2012.

- ^ "Blood Feast (2017) - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes.com. Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved September 28, 2017.

- ^ Alexander, Chris (June 27, 2017). "Blood Feast Remake Delayed Again and Gets R Rating". Coming Soon.net. Chris Alexander. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ^ Moore, Debi (June 28, 2017). "Blood Feast Remake Gets a New Rating and Date for its Theatrical Release - Dread Central". Dread Central.com. Debi Moore. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

Bibliography[]

- Palmer, Randy (2000). Herschell Gordon Lewis, Godfather of Gore: The Films. Jefferson, North Carolina and London: McFarland & Company. ISBN 0-7864-0808-1.

- Romer, Jean-Claude; Silver, Alain (2000). "A Bloody New Wave in the United States (July 1964)". Horror Film Reader. New York: Limelight Editions. ISBN 0-87910-297-7.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Blood Feast |

- Blood Feast at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Blood Feast at IMDb

- Blood Feast at the TCM Movie Database

- 1963 films

- English-language films

- 1963 horror films

- American films

- American splatter films

- Films directed by Herschell Gordon Lewis

- Films shot in Miami

- American independent films

- Films set in Florida

- 1960s serial killer films

- Something Weird Video

- Obscenity controversies in film

- American slasher films

- 1960s slasher films

- Films shot in Florida

- Video nasties

- Films about cannibalism

- American exploitation films

- 1960s exploitation films

- Films based on Egyptian mythology

- Inanna