Blue Banana

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

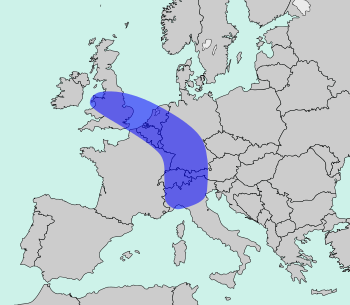

The Blue Banana (also known as the European Megalopolis or the Liverpool–Milan Axis) is a discontinuous corridor of urbanization spreading over Western and Central Europe, with a population of around 111 million.[1] The conceptualisation of the area as a "Blue Banana" was developed in 1989 by RECLUS, a group of French geographers managed by Roger Brunet.[2]

It stretches approximately from North West England through the English Midlands across Greater London to the European Metropolis of Lille, the Benelux states and along the German Rhineland, Southern Germany, Alsace-Moselle in France in the west and Switzerland (Basel and Zürich) to Northern Italy (Milan and Turin) in the south.[3][4]

History[]

The French geographer Roger Brunet, who observed a division between "active" and "passive" spaces, developed the concept of a West European "backbone" in 1989. He made reference to an urban corridor of industry and services stretching from northern England to northern Italy.[2] The name "Blue Banana" was dually coined by , and an artist adding a graphic to an article by in Le Nouvel Observateur. The color blue referred to either the flag of the European Community, or the blue collars of factory workers in the region.[5]

Brunet saw the "European Backbone" as the development of historical precedents, e.g. trade routes, or as the consequence of an accumulation of industrial capital. In his analysis Brunet excluded the Paris urban area and other French conurbations because of French economic insularity. His aim was a greater economic integration in Europe, but he felt that France had lost this connection by the 17th century as a result of its persecution of Huguenots and centralisation in Paris.[6][5] Later versions do, however, include Paris.[6]

In 1991, in the context of a study on behalf of the European Commission in support of its Regional Policy, researchers criticized the idea of the Blue Banana as a desirable formation, but not an empirical reality, identifying it as the result of regional competition in Europe. Furthermore, their diagram of the Blue Banana had more of a curve, still including Northern Italy, but ending at Barcelona. It also included Paris, and had the Anglo-Scottish border as its northern stem.[7] A study of the history of the Blue Banana as a concept refers to the Commission's study as a mistaken rejection of the Blue Banana from Brunet's original conception. From the research on the Commission's behalf, the Blue Banana represented a developed core at the expense of the periphery, whereas Brunet empirically viewed the Blue Banana as a region of development at Paris's periphery, beyond the French borders.[8] There are also considerations for an economically strong European pentagon with its borders Paris, London, Hamburg, Munich and Milan, with development axes towards the east (Berlin, Prague, Trieste).[9]

In the Italian media, the opinion was put forward that, according to EU data from 2013, the shape of the blue banana should be changed because Italian territory had lost its connection due to increasing de-industrialization. Only Lombardy could "keep up". In contrast, there are new economic development lines in Veneto, Friuli-Venezia Giulia and Slovenia through the connecting points of the maritime Silk Road. In particular, the port of Trieste, next to Gioia Tauro, the only deep-water port in the central Mediterranean for container ships of the seventh generation, is therefore particularly the target of investments. Transport via Trieste instead of northern ports such as Rotterdam and Hamburg shortens the delivery time from Shanghai by ten days and from Hong Kong by nine days, which significantly reduces transport costs and CO2 emissions.[10][11][12][13]

See also[]

- Belt and Road Initiative

- Demographics of Europe

- Four Motors for Europe

- Golden Banana

- List of metropolitan areas in the European Union by GDP

- Northeast megalopolis – a similar region in the United States

References[]

- ^ "The European Blue Banana". Eu-partner.com. 3 March 2011. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brunet, Roger (1989). Les villes europeénnes: Rapport pour la DATAR (in French). Montpellier: RECLUS. ISBN 978-2-11-002200-4. Archived from the original on 8 February 2021. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Gert-Jan Hospers (2002). Beyond the Blue Banana? Structural Change in Europe's Geo-Economy (PDF). 42nd EUROPEAN CONGRESS of the Regional Science Association Young Scientist Session – Submission for EPAINOS Award 27–31 August 2002. Dortmund, Germany. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2006.

- ^ Gert-Jan Hospers (2003). "Beyond the Blue Banana? Structural Change in Europe's Geo-Economy" (PDF). Intereconomics. 38 (2): 76–85. doi:10.1007/BF03031774. S2CID 52214602. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jacobs, Frank (31 December 2014). "The Blue Banana - the True Heart of Europe". Big Think: Your Daily Microdose of Genius. The Big Think, Inc. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Taylor, Paul (15 March 2015). "No more Blue Banana, Europe's industrial heart moves east". Reuters. Archived from the original on 4 March 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Kunzmann, Klaus R.; Wegener, Michael (September 1991). "The pattern of urbanization in Western Europe" (PDF). Ekistics. 350 (350–351): 291. PMID 12317364. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Faludi, Andreas (March 2015). "The 'Blue Banana' Revisited" (PDF). European Journal of Spatial Development. 56. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2018.

- ^ Karl-Peter Schön: Einführung. Das Europäische Raumentwicklungskonzept und die Raumordnung in Deutschland. In: Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung: Informationen zur Raumentwicklung, H. 3/4. Bonn: (2000).

- ^ Italy no longer belongs to the competitive regions. In: Corriere della Sera of August 25, 2013; Raffaele Ricciardi: Italy is losing competitiveness - only Lombardy in Europe. In: Repubblica of August 24, 2013.

- ^ Wolf D. Hartmann, Wolfgang Maennig, Run Wang: Chinas neue Seidenstraße (2017).

- ^ "Logistica, il colosso Duisport acquisisce il 15% delle quote dell'Interporto di Trieste" In: Il Piccolo, 15.12.2020.

- ^ New Silk Road: Everything that belongs to the mega project (German)

Sources[]

- Geza, Tóth; Nagy, Zoltán; Kincses, Áron (2014). European Spatial Structure. Saarbrücken: Lambert Academic Publishing. doi:10.13140/2.1.1560.2247. ISBN 978-3-659-64559-4.

- Brunet, Roger (April 2002). "Lignes de force de l'espace Européen" (PDF). Mappemonde (in French) (66): 14–19.

- Economic regions of Europe

- Demographics of Europe

- Geographical neologisms

- Metropolitan areas of the European Union

- Urban studies and planning terminology