Bobby soxer (music)

Bobby soxer is a term for the wildly enthusiastic, teenage female fans of 1940s traditional pop music, in particular that of singer Frank Sinatra.[1] Bobby soxers were usually teenage girls in high schools and colleges, who got their name from the popular bobby socks that they wore.[2] As a teenager, actress Shirley Temple played a stereotypical bobby soxer in the film The Bachelor and the Bobby-Soxer (1947).[3]

The presence of bobby soxers signalled a shift in American youth culture. Businesses and corporations noticed that they were able to profit off the burgeoning consumer power of teenagers — especially among girls — and began targeting products to younger buyers, creating a new subset of American culture.[4][5] Teenagers became more prominent in society as they participated in activities such as dancing and going to the movies.[6][7] Music and dancing grew more popular among teenagers in the 1940s; the most popular types of music were swing and jazz, which were favoured by bobby soxers.[8] The increased popularity of music made it a big part of the lives of bobby soxers, as they frequently discussed their favourite musicians with each other and bonded over records.[8]

Etymology[]

The origins of the phrase ‘bobby soxer’ date back to a 1943 Time article, which described teenage girls of the time as “little long-haired” girls with “round faces” that wore bobby socks and “worshiped Frank Sinatra.”[9] Another common phrase used was ‘bobby sox girls.’[10] The phrase derives from the ankle socks often worn by female high school students; these socks were usually paired with loafers or saddle shoes.[9] By the end of the 1940s, bobby soxers were unanimously defined as either just fans of Frank Sinatra or teenage girls who were obsessed with the fads and crazes of the time.[6] The phrase ‘bobby-soxer’ was often rejected by the girls themselves and instead promoted largely by the media.[9] The term has since been used by dictionaries to describe “an adolescent girl.”[11]

History[]

In the early twentieth century, teenage girls did not receive much attention from producers of consumer culture and popular culture.[12] Around this time, women began accessing the public sphere with the help of an increase in commercialised leisure.[13] This included public entertainment spaces such as cinemas and dance halls.[13] As women grew more involved with the public sphere, their desire to stay at home notably decreased; social commentators of the 1920s and 1930s noted that young Americans were spending less time at home with their parents and more time engaging in leisure activities with friends.[13] From this growing engagement in leisure activities came a notable rise in an interest in consumer culture among young girls, which coincided with a desire from businesses to speed up a growing development in the creation of teenage girls’ culture.[13] It was not until the 1940s that American advertisers began capitalising on the consumer power of teenagers — particularly teenage girls — and created a new market that focused on prolonging adolescence.[5] This boom also saw an immense rise in teenage consumer power in the American music industry, especially among young girls.

Singers such as Frank Sinatra became teen idols. Sinatra particularly proved popular; his signature croon was noted by psychologists for its “hypnotic quality” and “remarkable effect upon susceptible young women.”[10] Mark Duffett has described Sinatra’s December 1942 performance at the Paramount Theatre in New York City as “set[ting] the template” for female fans being part of the “spectacle” that would follow for artists such as Elvis Presley and the Beatles.[14] Sinatra was declared by The New York Times as "the first modern popstar" who "gave pop music a beating heart."[15] His early music was emblematic of puppy love as he sang from the perspective of a young man smitten with the girl of his dreams.[15] Swooning became a common practice among bobby soxers as a means of expressing their infatuation; this consisted of young women groaning dramatically and waving their arms in the air, then placing their hands on their foreheads before falling to the ground.[16] Parents feared that their bobby soxer children’s infatuation would impact their burgeoning sexuality and taint their innocence, but with Sinatra being married at the time, swooning was eventually not seen as a threat to the youth of bobby soxers.[16]

Music became much more popular among teenagers in the postwar period. Popular songs of the 1940s followed a consistent pattern of avoiding controversial subjects and reinforcing idealised traditional values.[17] The content of these songs often focused on courtships rather than taboo topics such as sex.[17] Such content proved to be popular among teenage girls, who celebrated what was happening in their lives, (i.e. dating) through song.[6] Bobby soxers enjoyed jazz and swing music, with dances and listening to the radio being two of the most popular activities among teenage girls.[6] Music and dance proved to be an integral part of teen culture in the 1940s, as they contributed to the formations of friend groups, the enjoyment of leisure activities and even more mundane activities such as homework.[6] Bobby soxers frequently engaged in debates over their favourite artists, bands and records, and they often made connections between their favourite songs of the time and important events occurring in their lives.[6]

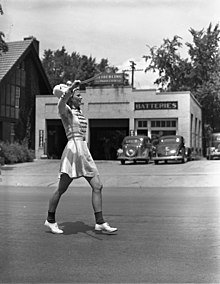

Fashion was also popular among bobby soxers. A typical bobby soxer outfit included bobby socks — the inspiration for their nickname — penny loafers or saddle shoes, Shetland sweaters and poodle skirts or blue jeans.[16] In addition to this ensemble’s association with bobby soxers, the combination of poodle skirts and ankle socks have been described as a symbol of the conception of American teenage culture.[6] An interest in fashion among young girls was encouraged by parents and magazine columnists alike, but the former typically imposed strict limits on expressing sexuality, which did not match the ever-changing definitions of what was acceptable for teenagers to be wearing.[6] However, the bobby soxer style was not merely a representation of femininity and good behaviour. A Life magazine pictorial on the bobby soxer style declared that the “‘changing fashions of language and youth indicate a healthy spirit of rebellion.’”[18][19] In addition to differing women’s styles, media scholar Tim Snelson notes, such ‘rebellious’ styles included a “‘craze for wearing men’s clothing’ and [a] combination of white bobby socks and ‘moccasin-type shoes’...” [19]

When the 1950s arrived, the ‘teen revolution’ was in full swing. A 1956 edition of the Parent Teacher Association (PTA) magazine declared that “the trouble with teenagers started when some smart salesman made a group of them in order to sell bobby sox.”[6] By then, teenagers began listening to rock ‘n’ roll music while an explosion of mainstream teen culture occurred. As Frank Sinatra began performing more mature music, artists such as the Beatles and Elvis Presley became new teen idols.[20] However, as bobby soxers grew into their twenties, they soon followed teenage norms of the time and began settling down with husbands and children.[20] The bobby sox style remained popular well into the 1950s, but original bobby soxers left their fanatic days behind as they entered adulthood and prioritised work or family life.[6]

Portrayal of bobby soxers[]

Film and television[]

The inclusion of bobby soxers in film and television began during the early 1940s, almost immediately after the phrase ‘bobby soxer’ came to prominence in the mainstream media. Initially, young girls were portrayed as delinquents in B-list films.[21] Such portrayals came at a time when cultural fears in the United States centred around female youths engaging in sexual activity; these films corresponded with the fears of the general public over a rise in delinquency among young girls.[21] Bobby soxers were later portrayed in mainstream films such as The Bachelor and the Bobby Soxer (1947), starring Shirley Temple and Cary Grant. These films often used a heavy amount of slang and sometimes unrealistic stereotypes in their on-screen portrayals of bobby soxers.[22] Hollywood producers wanted to use child stars such as Temple and Jane Withers for teenage roles as actresses such as Judy Garland successfully transitioned into more adult performances; however, Temple and Withers’ performances were often critiqued, and their films failed at the box office.[22]

Media[]

Most media outlets portrayed bobby soxers to be highly enthusiastic, sometimes to the point of hysteria. Newspapers noted bobby soxers for their dedication to Frank Sinatra and other teen idols. A 1945 Guardian article reported on one bobby soxer fan who “[was] known to have sat through 56 consecutive performances, which means about eight consecutive days.”[10] Bobby soxers were also reported to have waited for so long to see Sinatra that they experienced hunger, fatigue and dizziness.[10] Bobby soxers were portrayed to be disinterested in the crisis of World War II. Seventeen magazine — which launched in 1944 to cater to teenage girls — published letters from readers who wrote asking for “more articles on dating and shyness...stories like those on atomic energy are very boring.”[18]

Impact on teen culture[]

Bobby soxers are not the first known enthusiastic ‘fans’ of musicians; fan culture dates back to the seventeenth-century, and fanatics of musicians have been documented as coming to prominence in the 1860s.[14] However, they were the first to partake in modern American teenage culture and played a significant role in its development. Bobby soxers are continuously credited as the predecessors of enthusiastic fans of artists such as the Beatles, who would go on to spark a major cultural movement of their own.[16]

Bobby soxers and their teenage peers had a considerable impact on the financial aspects of teen culture in the years following their entry into American culture. Broadly speaking, the teen consumer market exploded greatly in the 1950s; it reportedly amounted to approximately $10 billion by 1959, with expectations at the time estimating it would double by 1970.[23] In 1961, for instance, records — which sociologist Jessie Bernard describes as a crucial aspect of teenage culture — were reported to sell $75 million worth of copies annually.[23] The girls that participated in teenage consumer culture were known as “teen tycoons” due to their consumer power.[23] The likes of such power can still be seen today among teenage girls as youth consumer culture has expanded immensely and has become a paramount component of teenage culture.[24]

In addition to material purchases, the power of bobby soxer friend groups was equally important to the teen culture. Former bobby soxers who became housewives with part-time work developed a noticeable peer culture with each other, setting the stage for teenage culture to grow in years to come.[25] Author Kelly Schrum noted that at the start of the 1900s, teenage culture was insignificant and essentially non-existent; by the start of the 2000s, teenagers were incredibly prominent in America with a very powerful cultural presence and high consumer power.[24] Today, the number of research companies that specialise in researching and advertising to teenagers has increased immensely, and the market for teenage girls has become much larger and more profitable than it has ever been.[24]

See also[]

| Look up bobby soxer in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Bubblegum pop

- Teenybopper

References[]

- ^ Green, Jonathan (2005). Cassell's Dictionary of Slang. Sterling Publishing Company. p. 145. ISBN 9780304366361.

- ^ Sickels, Robert (2004). The 1940s (American Popular Culture Through History). ABC-CLIO. p. 36. ISBN 9780313312991. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ Nash, Ilana (2005). American Sweethearts: Teenage Girls in Twentieth-century Popular Culture. Indiana University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-253-21802-5. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ Smith, Kathleen E.R. (2015). "Jitterbugs and Bobby-Soxers". God Bless America: Tin Pan Alley Goes to War. The University Press of Kentucky. pp. 153–159. ISBN 9780813122564.

- ^ a b Smith 2015, p. 153.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Schrum, Kelly (2004). Some Wore Bobby Sox: The Emergence of Teenage Girls' Culture, 1920-1945 (1st ed.). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781349731343.

- ^ Schrum 2004, p. 8.

- ^ a b Schrum 2004, p. 98.

- ^ a b c Schrum 2004, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d "Frank Sinatra and the 'bobby-soxers' | 1940-1949 | Guardian Century". www.theguardian.com. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- ^ "Definition of BOBBY-SOXER". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- ^ Schrum 2004, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d Schrum 2004, p. 15.

- ^ a b Duffett, Mark (2013). Understanding Fandom: An Introduction to the Study of Media Fan Culture. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 6–8. ISBN 978-1-6235-6585-5.

- ^ a b Holden, Stephen (December 11, 2015). "Frank Sinatra: A Hundred Years On, the Voice Resonates Still". The New York Times.

- ^ a b c d Conger, Cristen (n.d.). "How Bobby Soxers Worked: Frank Sinatra and Bobby Soxers". HowStuffWorks. Archived from the original on 2012-04-19.

- ^ a b Mirsch, Paul M. (1971). "Sociological approaches to the pop music phenomenon". American Behavioral Scientist. 14 (3): 371–388. doi:10.1177/000276427101400310. hdl:2027.42/68295. S2CID 32342634.

- ^ a b Snelson, Tim (2012). "From juke box boys to bobby sox brigade: Female youth, moral panics and subcultural style in wartime times square". Cultural Studies. 26 (6): 872–894. doi:10.1080/09502386.2012.687753. S2CID 142532788.

- ^ a b Snelson 2010, p. 885.

- ^ a b McNearney, Allison. "1950s Parents Had No Idea What Their Kids Wanted to Do at Parties". HISTORY. Retrieved 2021-05-16.

- ^ a b Snelson 2010, p. 878.

- ^ a b Schrum 2004, p. 142-144.

- ^ a b c Bernard, Jessie (1961). "Teen-age culture: An overview". The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 338 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1177/000271626133800102. S2CID 146519820.

- ^ a b c Schrum 2004, p. 175.

- ^ Schrum 2004, p. 18.

- 1940s fashion

- 1950s fashion

- Slang terms for women

- Music fandom

- 1940s neologisms

- Youth culture in the United States