Boomerang dysplasia

| Boomerang dysplasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Dwarfism with short, bowed, rigid limbs and characteristic facies |

| |

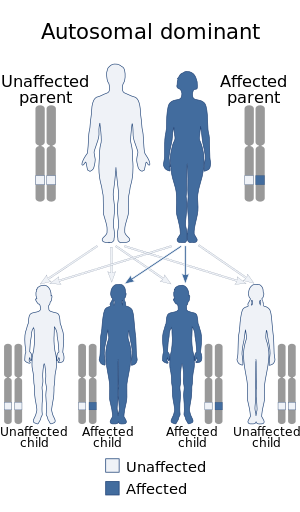

| Boomerang dysplasia has an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Boomerang dysplasia is a lethal form of osteochondrodysplasia[1] known for a characteristic congenital feature in which bones of the arms and legs are malformed into the shape of a boomerang.[2] Death usually occurs in early infancy due to complications arising from overwhelming systemic bone malformations.[1]

Osteochondrodysplasias are skeletal disorders that cause malformations of both bone and cartilage.

Presentation[]

Prenatal and neonatal diagnosis of boomerang dysplasia includes several prominent features found in other osteochondrodysplasias, though the "boomerang" malformation seen in the long bones is the delineating factor.[2]

Featured symptoms of boomerang dysplasia include: dwarfism[3] (a lethal type of infantile dwarfism caused by systemic bone deformities),[4] underossification (lack of bone formation) in the limbs, spine and ilium (pelvis);[1] proliferation of multinucleated giant-cell chondrocytes (cells that produce cartilage and play a role in skeletal development - chondrocytes of this type are rarely found in osteochondrodysplasias),[5] brachydactyly (shortened fingers) and micromelia (undersized, shortened bones).[2]

The characteristic "boomerang" malformation presents intermittently among random absences of long bones throughout the skeleton, in affected individuals.[3][6] For example, one individual may have an absent radius and fibula, with the "boomerang" formation found in both ulnas and tibias.[6] Another patient may present "boomerang" femora, and an absent tibia.[3]

Cause[]

Mutations in the Filamin B (FLNB) gene cause boomerang dysplasia.[1] FLNB is a cytoplasmic protein that regulates intracellular communication and signalling by cross-linking the protein actin to allow direct communication between the cell membrane and cytoskeletal network, to control and guide proper skeletal development.[7] Disruptions in this pathway, caused by FLNB mutations, result in the bone and cartilage abnormalities associated with boomerang dysplasia.[citation needed]

Chondrocytes, which also have a role in bone development, are susceptible to these disruptions and either fail to undergo ossification, or ossify incorrectly.[1][7]

FLNB mutations are involved in a spectrum of lethal bone dysplasias. One such disorder, atelosteogenesis type I, is very similar to boomerang dysplasia, and several symptoms of both often overlap.[8][9]

Genetics[]

Early journal reports of boomerang dysplasia suggested X-linked recessive inheritance, based on observation and family history.[3] It was later discovered, however, that the disorder is actually caused by a sporadic genetic mutation fitting an autosomal dominant genetic profile.[8]

Autosomal dominant inheritance indicates that the defective gene responsible for a disorder is located on an autosome, and only one copy of the gene is sufficient to cause the disorder, when inherited from a parent who has the disorder.[10]

Boomerang dysplasia, although an autosomal dominant disorder,[8] is not inherited because those afflicted do not live beyond infancy.[1] They cannot pass the gene to the next generation.

Diagnosis[]

This section is empty. You can help by . (July 2017) |

Treatment[]

This section is empty. You can help by . (July 2017) |

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Bicknell LS, Morgan T, Bonife L, Wessels MW, Bialer MG, Willems PJ, Cohen DH, Krakow D, Robertson SP (2005). "Mutations in FLNB cause boomerang dysplasia". Am J Med Genet. 42 (7): e43. doi:10.1136/jmg.2004.029967. PMC 1736093. PMID 15994868.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Wessels MW, Den Hollander NS, Dekrijger RR, Bonife L, Superti-Furga A, Nikkels PG, Willems PJ (2003). "Prenatal diagnosis of boomerang dysplasia". Am J Med Genet A. 122 (2): 148–154. doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.20239. PMID 12955767. S2CID 42013969.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Winship I, Cremin B, Beighton P (1990). "Boomerang dysplasia". Am J Med Genet. 36 (4): 440–443. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320360413. PMID 2202214.

- ^ Kozlowski K, Tsuruta T, Kameda Y, Kan A, Leslie G (1981). "New forms of neonatal death dwarfism. Report of 3 cases". Pediatr Radiol. 10 (3): 155–160. doi:10.1007/BF00975190. PMID 7194471. S2CID 31143908.

- ^ Urioste M, Rodriguez JL, Bofarull J, Toran N, Ferrer C, Villa A (1997). "Giant-cell chondrocytes in a male infant with clinical and radiological findings resembling the Piepkorn type of lethal osteochondrodysplasia". Am J Med Genet. 68 (3): 342–346. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19970131)68:3<342::AID-AJMG17>3.0.CO;2-T. PMID 9024569.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kozlowski K, Sillence D, Cortis-Jones R, Osborn R (1985). "Boomerang dysplasia". Br J Radiol. 58 (688): 369–371. doi:10.1259/0007-1285-58-688-369. PMID 4063680.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lu J, Lian G, Lenkinski R, De Grand A, Vaid RR, Bryce T, Stasenko M, Boskey A, Walsh C, Sheen V (2007). "Filamin B mutations cause chondrocyte defects in skeletal development". Hum Mol Genet. 16 (14): 1661–1675. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddm114. PMID 17510210.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Nishimura G, Horiuchi T, Kim OH, Sasamoto Y (1997). "Atypical skeletal changes in otopalatodigital syndrome type II: phenotypic overlap among otopalatodigital syndrome type II, boomerang dysplasia, atelosteogenesis type I and type III, and lethal male phenotype of Melnick-Needles syndrome". Am J Med Genet. 73 (2): 132–138. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19971212)73:2<132::AID-AJMG6>3.0.CO;2-W. PMID 9409862.

- ^ Greally MT, Jewett T, Smith WL Jr, Penick GD, Williamson RA (1993). "Lethal bone dysplasia in a fetus with manifestations of Atelosteogenesis type I and Boomerang dysplasia". Am J Med Genet. 47 (4): 1086–1091. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320470731. PMID 8291529.

- ^ "Boomerang dysplasia". Genetics Home Reference. 2016-02-22. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

External links[]

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Congenital disorders

- Rare diseases

- Autosomal dominant disorders